This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I mean no disrespect to religion—or to professional wrestling for that matter—but there is a definite similarity between them. The wrestling fan, like the religious believer, must have faith. The fan must believe that the horde of strange beings who engage each other in the ring—the lumberjacks and Japanese and Chinese and Russians and Nazis and Mongols and Samoan chiefs, and baby blimps and even mummies back from the dead—are exactly what they appear to be, that their stomach claws and death locks and head bonks are real threats to their opponents, and that all their posturing and antics in the ring are sidelights to a true fight to the finish over something important.

If the fan maintains his faith, wrestling will reward him with an arena in which the good and beautiful meet the evil and ugly before his very eyes. But if his faith wavers even on the slightest matter, the fan, like the apostate, finds he can no longer believe anything he once believed. He sees wrestling for what, to the faithless, it is—a sham, a sell, a con job; the place where the ultimate in cynicism—the performers—meets the ultimate in gullibility—the audience.

The cool logician would assume that the fan who’d seen wrestling as a sham would never return to see the sham again. The cool logician would be wrong. There are no atheists in foxholes, and there are no faithless fans at ringside, faithless as they might be anywhere else. Every wrestling match is a battle between a good man and a bad man. The wrestlers who represent the good—“baby faces” they’re called in the trade—look nice, fight fair, and heroically accept the adulation of the crowd. But the wrestlers who represent evil, the “heels,” the ones who would scorn or revile any confused fan who might ask them for autographs, the ones who pull hair and gouge eyes and hit with closed fists and, worst of all, lie to the referee, the ugly ones, the ones who smirk and scowl and lurk nastily in their corner waiting for the match to begin, these are the ones who make wrestling come alive. It is the heel who changes the faithless to faithful once again. Someone to cheer for is one thing, but nothing gains converts like hatred.

One of the greatest heels, Dr. Boris Malenko, led me to the light, and my world is diminished now that he is no longer on the scene. Dr. Malenko was a Russian physicist who came to Texas specifically to capture the World Wrestling Association championship belt, take it back to Russia, and nail it to the wall of the Kremlin. He was foiled, but only barely. Malenko’s final defeat came one Friday night in Houston. Masked and billed as “Mr. Houston”—Russians, as we know, are good at covering their true identity—he was pitted against Wahoo McDaniel, part native American Indian, former all-American football player at Oklahoma, former New York Jets linebacker, and now a resident of Midland.

Malenko and Wahoo were fastened by the wrist at opposite ends of a long chain. Both men vowed to fight until one man had dragged his foe twice around the ring. Wahoo, the American, less familiar with the dirty tricks of fighting while chained than the devious Russian, found himself thrown from the ring in the early going and his face bloodied by Malenko’s vicious lashing with the chain. But such setbacks don’t discourage a man with Wahoo’s fundamental American virtues, and at the end of the match—to the crowd’s wild cheering—a bloodied but proud Wahoo dragged Malenko around the ring, and the godless Russian’s plot to take the belt to the Kremlin was ended. Such victories aren’t “fixed”; they are made in heaven.

I do, as I said, miss Dr. Malenko, but that doesn’t mean that I cheered for him. Even for the faithless who recognize wrestling as a sham, it is impossible to be for hanging the world championship belt in the Kremlin. The villains of the wrestling ring, Malenko included, always manage to make themselves so thoroughly nasty that even the most cynical spectator could not find it in himself to cheer them on; and, sure enough, wrestling fans down to the very last one boo the heel and cheer the baby face. But it is the heels who earn, if not my support, at least my affection. It is our enemies, after all, and not our heroes, who define us, and for our own good we need enemies that make us worthy of ourselves. Malenko was worthy of us, since he managed to pose a threat that was global in its implications, transcending politics and ideology. Fortunately for all humanity, there is at least one worthy enemy, the Mongolian Stomper, wrestling in Texas today.

The man who helped me appreciate the Stomper did so unwittingly. He is a former professional wrestler whom we shall know as Karl. Today he is a professor at a distinguished university. His fortunes and indeed his personality have changed dramatically from the days when, as a poor and desperate graduate student with a family to feed, he turned to professional wrestling for his livelihood.

I needed Karl’s help because professional wrestling is a closed world, closed in the same way and for the same reason as the worlds of carneys, circuses, racetrack touts, magicians, spies, and every other occupation which depends upon the hand being quicker than the eye. Everyone in wrestling shares a secret—that a wrestling match is a staged show. The only people let in on the secret are the wrestlers, promoters, and referees—only the people, in other words, who need to know. Someone who knows is called “wise.” Karl, after having been out of wrestling for almost a decade, took his young son to a match and, through some old contacts, was able to take his boy back into the dressing room before the show began. One of the wrestlers, famous for his uncontrollable temper in the ring, began to huff and puff threateningly. “Hey, wait a minute, man,” Karl said. “I’m wise.”

“Oh, I’m sorry,” the wrestler said. “I didn’t know.” He shook hands with Karl and then returned to quietly lacing up his boots.

Obviously no one who depends upon wrestling for a living is going to wise up anyone on the outside. And there is some old loyalty on the part of people who have been in wrestling that won’t let them turn on the world that once took them in. Even Karl, when people ask him today whether or not wrestling is real, replies, “Well, I was hospitalized twice.” He does not go on to say that the first time was for a sore that became infected in the ring and the second was for a badly bruised leg, an injury aggravated by wrestling but originally incurred when he bumped into a chair as he stumbled out of bed to answer the telephone.

Karl got started in wrestling through a promotion stunt that is as old as wrestling itself. Occasionally, when the suspicions of fakery grow too loud or when the promoter thinks it would help draw in crowds, a wrestler will be billed as willing to meet any challenger who cares to enter the ring. This is usually a safe bet for the promoter. Never think, because professional wrestling is what it is, that all wrestlers are patsies. Many of them, like Chris Taylor, the 400-pound Olympic medal winner who is now a pro, have been champion college wrestlers and know how to handle themselves in a ring against the best opponents. A man off the street stands little chance—no matter how tough he thinks he is—unless he has had some training and experience in wrestling.

Now Karl was never a champion in college but he did considerable wrestling there. The son of a roughneck in Port Arthur, he managed, to his amazement, to be admitted to Texas A&M. By the time he graduated his amazement had changed to a single-minded determination to become a scientist, and, after six months working in the oil fields, he entered graduate school at Memphis State University in Tennessee in the early Sixties. By this time he was married and had two children. He had been making good wages in the oil fields but in graduate school his scholarship granted him only $120 a month. It wasn’t enough. He had to go into debt to buy groceries, his children were sick that winter, he hated his wife’s having to work and he took a job in a women’s shoe store, work that was a blow to his pride. Then he saw an ad in the newspaper that offered any amateur who was willing to enter the ring against a vicious heel named Spider Galento $1 for every minute he lasted, or $100 if the amateur won. Karl didn’t think he had a chance for the $100, but he was so poor that the chance to win even $10 or $15 sounded inviting.

Karl had never been to a professional wrestling match and had seen them only once or twice on television. He had, however, been part of a fledgling wrestling program at A&M and had wrestled in tournaments against some of the best college wrestlers in the Southwest. He was big—well over six feet and well over 200 pounds—quick, and shrewd. One small fact had always struck him as important about professional matches: they frequently lasted as long as an hour. He knew that a college wrestler who followed the strictest diet and most rigorous training routine wrestled to time limits of nine or fifteen minutes, and that even for the best athlete in the best condition, the sport was too demanding for the participants to go much longer than that. Karl didn’t think about this enough to connect on what it meant, but he did wonder how the pros, who were often very clearly not in good shape at all, managed to last so long. He went to the wrestling promoter’s office, put on an I’m-just-a-country-boy-from-Port-Arthur-and-I-don’t-know-much-about-rasslin’-but-I-think-I-can-beat-that-damn-Galento act, and got put on the card two weeks away.

Karl was no longer in the kind of condition he had been in as a college wrestler or even as an oil field worker. He spent the two weeks trying frantically to get in shape. The morning of the match he invested some of his meager capital in a pair of cheap sneakers, which he wore into the ring along with an old pair of gray athletic socks which kept falling down around his ankles, and an old swimsuit with a rip in the back. He knew he looked hopeless and pathetic, which was part of his plan.

Inside the ring he went to his corner. A small crowd of spectators gathered and, to his amazement, held up their programs for him to sign. “Me!” he said. “You want my autograph?” It was then that he got his first hint of the almost mystical appeal of wrestling to its fans. He was wrestling in the old Ellis Auditorium in Memphis. It was filled to capacity that night, since the main event pitted Billy Wicks against the hated Sputnik Monroe, yet another Russian and, of course, a heel. In those days the Ellis Auditorium had a special section “For Colored Only” and one of Sputnik Monroe’s favorite tricks, being a Russian, was to play to that section, blowing kisses, even bowing to their cheers, while the whites in the audience fumed in rage.

Spider Galento entered the ring. Years before he had been an AAU champion but now he was a hated heel. Dark haired, somewhat past his best weight, he scowled as the crowd booed him. Karl, meanwhile, shuffled his feet in his corner, looked out of the sides of his eyes at Galento, wiped his palms on his trunks, all in an effort to appear that he would rather be anywhere else than where he was. Surreptitiously he felt his pulse and was surprised to find it normal.

The referee called Karl and Galento into the center of the ring. “How ya doin’?”

“OK,” Karl said.

“I’ll take it easy with you,” Galento whispered. “Don’t worry.”

Karl didn’t say anything, but he went back to his corner with his stomach churning in anger. Galento had offended his pride even though his words were meant more as kindness than affront. Karl learned later that Galento’s instructions were to let the “gunsel,” as fighters off the street are called, last long enough to make a few dollars and then take him down. If he couldn’t win, Galento was supposed to get himself disqualified in order to save face with the crowd.

The bell rang. Galento came out of his corner quickly. Karl let him get to the middle of the ring before turning around, planting his feet firmly, and placing his hands in a referee’s position collegiate wrestlers frequently use for starting a match. Galento stopped in his tracks and his mouth dropped open. Karl’s humble posturing had worked; he had gained the first advantage even if it was psychological rather than physical. The two men began to circle each other warily.

Karl had intended to fight defensively. He had thought the best way to last ten minutes was to “make like a rock,” the wrestling equivalent of Ali’s “rope-a-dope.” But he was still mad about what Galento had said before the match and he gained confidence from having the first psychological advantage. He defended himself against Galento for a while, slipping holds without trying any counter maneuvers. Just when he thought he’d lulled Galento into believing that he was never going to attack, Karl slipped one hold, saw an opening, and tried to throw Galento. But Spider Galento wasn’t going to be fooled twice by a gunsel in an auditorium filled with eager fans. He evaded Karl easily, and, with Karl momentarily off balance, Galento managed to get him in a front headlock. He squeezed Karl’s head tighter and tighter.

The referee, leaning down as if he were checking the hold, whispered to Karl, “How about it?”

“How about what?”

“Want to quit?”

“Hell, no,” Karl said. He had already been in the ring longer than ten minutes, but now, he thought, if he could break this hold, he could go back to his defensive tactics and last for the rest of the half-hour time limit. Every minute meant another dollar.

As Galento applied more pressure, Karl tried to get his feet under him so he could lift Galento off the ground. It almost worked once, but Galento moved back a few steps and Karl lost his leverage. Try as he would, Karl never came that close to breaking the hold again. The pain as Galento twisted his head and squeezed his skull was something Karl had vowed he would endure, but the weakness and lack of breath eventually took their toll. He tried again to lift Galento. Galento moved again and this time, much to his relief, Karl was able to hook his foot over the lower rope. The referee, according to the rules, made Galento break his hold.

Karl, standing up straight for the first time in several minutes, gasped for breath. Fortunately, keeping the hold had worn down Galento almost as much as enduring it had worn down Karl. He decided to make like a rock again, use no offensive moves, and hope Galento couldn’t break through his defense. Galento couldn’t. The two men stood in the middle of the ring straining against each other in a kind of mutual bear hug. The fans started booing. Karl was mystified. He was wrestling with all the force he could muster, countering everything Galento tried, and, instead of applauding his skill and endurance, the fans were booing. One man yelled, “What are you fellas doin’—dancing?”

Karl was struck with his second revelation about wrestling that night. “They must want blood,” he whispered to Galento.

“Yeah, that’s exactly what they want,” Spider Galento said.

Encouraged by the boos, Galento backed away from Karl and shrugged to the crowd. They booed louder. Galento wrestled a little more, backed away, and shrugged again. A solid, constant wave of boos bore down on Karl in the ring. He started to glance around him and just then, Galento rushed him and hit him with a roundhouse right to the nose. The boos changed immediately to deafening cheers. Before Karl could react, Galento followed with a left and then ran from the ring. The referee stood in front of Karl and blocked his pursuit. Karl swung at the referee. “Damn it, you won,” the ref said. “He hit you. I disqualified him. Stop it or I’ll disqualify you, too.”

That stopped Karl immediately. Mad as he was at Galento, he didn’t want to lose that $100. He got paid off in $1 bills. The next morning he couldn’t stand up straight, and he hobbled around for four days before he recovered completely.

He fought two more times, both against ex-college wrestlers and both times he earned a draw. The main event on the night of Karl’s second match was the Baby Blimp against a live bear. The bear won. After his third match, Karl returned to his locker to find Johnny Reb, who was part of a troupe of wrestlers who traveled on weekends to small backwoods towns in Tennessee and Arkansas. They had their own ring, did their own promotion, and split the gate between them. Johnny Reb asked Karl if he’d be interested in joining them. When Karl said that he might be, it was Johnny Reb who, starting that night, began to wise up Karl.

It’s not really that wrestlers lie about what they do. One professional told me that any college wrestler, no matter how good he was, had to train for a long time before he could become a pro. That’s true, but what it really means is that the amateur, in order to become a pro, must unlearn everything he’s learned. When Johnny Reb was wising up Karl, the first thing he did was tell Karl to get him in a headlock. Karl did, exerting only moderate pressure. “Hey, wait,” Johnny Reb said, “ease off.” Karl released his pressure about halfway. “No, man,” Johnny Reb insisted, “I said ease off.” Finally Karl released his pressure until his arm was just barely touching Johnny Reb. “That’s it,” Johnny said then. “It’s supposed to be light. Like a feather.”

Karl would eventually get good enough wrestling with Johnny Reb’s backwoods troupe to return to the Ellis Auditorium as a main attraction. He wrestled for several years in a circuit that included all the major cities in Tennessee and, when he left to continue his studies in Baltimore, he wrestled for a while there. Everywhere it was the same. If a wrestler asked another, “How’d it go?” the reply, if the match had gone well, would be, “Like a feather,” or simply a touch of the fingertips against the other’s shoulder, a touch meant to be light as a feather against the skin.

Karl learned to pull punches by practicing with a balloon. The idea was to swing so as to touch the balloon but not move it. Here in Texas one used to, and may still, be able to see wrestlers in the Dallas Athletic Club practicing drop kicks that won’t pop a balloon stuck on the wall, and putting exotic, painless holds on one another. Karl learned all that. He learned how to get thrown over someone’s head and land without hurting himself. He learned to stamp his foot as he delivered a blow so the sound of his foot covered the lack of any sound caused by the blow. He learned to “sell” a hold, that is, acting in pain, grimacing, pounding the mat in agony, or snapping his head back at the exact moment a punch would have landed.

He learned the three ways of drawing blood, a very important skill since many wrestling fans believe that, although some of the matches may be staged, the matches where blood is drawn are real. One way is to break a capsule of stage blood. Another is called a “blade job.” The wrestler hides a razor blade or other small, sharp piece of metal in his trunks. The blade is wrapped in tape so that only one corner remains exposed; when the proper moment in the match comes, the wrestler pulls the blade from his trunks, hiding his actions from the audience as best he can, and cuts himself on the forehead. A cut there bleeds profusely but isn’t any more dangerous than a nick from a razor while shaving. The third way is known as “the hard way.” One wrestler puts a headlock on the one who is going to bleed. He pulls his head-locked opponent’s eyebrow up so the skin just above the eye is drawn tightly over the eyebrow. Then he delivers a sharp, glancing blow with his knuckles that cuts the skin against the edge of the bone. When Karl agreed to take it the hard way, he told his opponent he had one chance. ‘‘If you don’t cut me the first time, don’t hit me anymore. I don’t want you out there beating all night on my eyes.” Karl also told his opponents to leave his ears and his nose completely alone. “I’m not going to be doing this all my life,” he said. “I want to look the same after wrestling as I did before.” Not all wrestlers felt that way. Karl had seen wrestlers have their ears pounded on in the dressing room. No fan would know that the resulting cauliflower ears were not the legacy of the years of rough matches the wrestler had endured in the ring.

But the most important thing a wrestler needs to learn cannot be taught. Part of it is an instinct for showmanship and an understanding of how to please a crowd, and part of it is an instinct for improvisation, an ability to create an exciting wrestling match as it goes along. During wrestling matches, just as in jazz concerts, most of what happens is spontaneous. The jazz musician has a basic melody where his improvisation begins; he works from the known to the unknown. A wrestler knows the “finish,” the final result of the match, and that is where his improvisation must end; he works from the unknown to the known. Which is why jazz is an art and wrestling is an exhibition.

The point of the exhibition, as Karl came to believe, was to excite the crowd just to the point of riot; he marveled how two wrestlers who had never seen each other before could walk into the ring, knowing only the finish, and work the crowd into a frenzy, how the heel could make an entire auditorium loathe him and the baby face inspire slavish adulation. Karl generally played the baby face. He enjoyed having other people think of him as a hero—enjoyed it up to a point. He felt guilty, too, knowing he was only a paper hero. But one night he played the heel. To his grim satisfaction, he discovered he had the knack of exciting instant hatred—the more the crowd hated him, the more he was inspired to devilry in the ring. He learned the heel’s private satisfaction—the crowd may hate him, but he has the solace of knowing that underneath the sham he’s not that bad. The baby face has the burden of knowing that underneath the sham, he’s not that good.

Karl hadn’t seen a wrestling match for almost five years when we went to the Sam Houston Coliseum in Houston one Friday night. He had left wrestling on something of a sour note after working a few times in the East because he had become suspicious of the local promoter. After he quit, although he retained enough loyalty that he seldom wised up people when he was asked about wrestling, he nevertheless began to feel ambivalent about his old livelihood. “It’s such a sell,” he told me as we walked toward our seats at ringside. Then, sitting down, he said, “Even that’s not so bad. The worst part is having your face down on the mat and seeing all those little black hairs embedded in the canvas. Damn those mats get filthy.”

The mat in Houston seemed to be no exception. An expanse of gray-to-purple canvas elevated about four feet off the coliseum floor, it looked quiet and almost flimsy under the hot, white lights suspended over it. The matches hadn’t started yet, so the house lights were up, too, and a look around at the crowd, now taking their seats on the floor near the ring or in the tiers that started at the edges of the floor and rose clear to the ceiling, revealed that there were about as many men as women and many of them were mothers and fathers with kids in tow. There were whites, blacks, Chicanos, from young tough-looking teenagers to old ladies with pale skin sagging beneath layers of powder. On the floor around Karl and me everyone was smoking or eating or drinking and the air was thick with the mingled smells of cigarettes, cigars, popcorn, beer, hot dogs. As the evening wore on it became impossible to walk without sloshing through spilled beer or crushing paper boxes, paper cups, and cigar butts beneath your feet. In addition to this epidemic oral fixation, the crowd seemed tense and inflammable, but not at all frightening. Their attention, expectation, and aggression were focused on the ring.

The main event that night matched Jose Lothario, long a favorite with Houston wrestling crowds, against the Mongolian Stomper. I had seen the Stomper in Houston and in San Antonio and, although he didn’t have the same effect on Karl that he had on me, the Stomper had occupied my thoughts more than any other wrestler. He had given himself so completely to his role that he really seemed to be a member of the ancient Asiatic hordes, incapable in the modern world of being anything but a wrestler, and an evil one at that. He is completely hairless except for his dense black eyebrows, beneath which two huge eyes, black as obsidian, glower at the world. A little over six feet tall, extremely muscular with thick shoulders and arms and a huge, powerfully developed chest, he walks toward the ring wearing a ragged sheepskin vest and keeping his head down but warily turning it from side to side as he moves through the audience.

He looks so ferocious that it’s impossible to imagine him reading or writing or drinking beer from a glass or performing any of the other graces of civilized men. Since he is supposed to speak only Mongol, he allows his manager—one James J. Dillon—to talk for him. Dillon, a short, somewhat pudgy man with yellow-white hair who is given to wearing flashy polyester suits and platform shoes and chewing on a thick, never-lit cigar, accompanies the Stomper to the ring. Dillon has a genius for antagonizing wrestling fans—“How’d you pay to get here?” he shouted at one heckler. “Did the welfare checks arrive today?”—and at ringside he pulls sneaky tricks like dashing into the ring to aid the Stomper when the referee isn’t looking. He also seizes the house microphone and babbles instructions to his wrestler in what is supposed to be Mongolian.

“Buba ruba be baba,” he shouts, and the Stomper will stop what he’s doing in the ring, cock his head like a cat trying to catch a sound, and then, having heard, nod his grim and sinister assent.

The Stomper’s most powerful weapon is, naturally enough, the Stomp. With his opponent flat on his back in the ring, the Stomper lifts both his opponent’s legs by the feet, spreads them apart, and then stomps on an area near the heart. This is supposed to have the temporary effect of stopping the heart and rendering the unfortunate victim immobile. In San Antonio I saw the Stomper put the Stomp on one hapless wrestler, supposedly a noble of a Samoan tribe. The Samoan lay prostrate in the ring, and the Stomper was about to fall on him for the pin that would end the match, when James J. Dillon shouted some of his gibberish into the ring. The Stomper listened. Instead of taking the fall then, he tangled the unconscious Samoan in the ropes, stomped him two or three more times, and then pinned him for the count of three. It’s this combination—the barbaric force of the Stomper and the merciless conniving of the evil Dillon—that makes the Stomper such a worthy enemy. It is not merely, as with Malenko, the threat of Communism he brings to the ring. The Stomper’s crude strength and Dillon’s barbaric yawp threaten civilization itself.

Karl, as I said, was not so taken. By the time of the main event his reactions to seeing wrestling again had changed from disgust, to nostalgia, to an unexpected appreciation for the antics of the performers, to disgust again. At first he enjoyed predicting the outcome of the matches. When two baby faces entered the ring together he immediately declared that they would fight to a draw. And that was what happened. “Friendly competition,” Karl said, as the two fighters hugged each other after the match. They had simply run around the ring putting one hold after another on each other. “You can see now why they need heels,” Karl said. “It’s too damn dull otherwise.” He emptied one beer and started on another.

After the first two matches we moved from ringside to seats on the last row at the top of the coliseum. Below us we could see the ring, the whole crowd, the brightly lit tunnels going back into the dressing rooms, and the thick shafts of smoke rising toward the ceiling. We drank some more beers and watched the parade of wrestlers go through their maneuvers. Below us people cheered and shouted, threw paper cups, and jumped out of their seats; eventually their enthusiasm and spontaneity carried even to us. The semifinal event was a tag-team match in which the heels were constantly tripping over the ropes as they came into the ring and hitting one another by mistake when the baby faces would duck suddenly beneath their blows. Karl and I started cheering when the baby faces started gaining the upper hand and turned the tide of battle their way. We were, suddenly, in spite of ourselves, among the faithful. But when the match was over and the spell was broken, Karl became depressed and moody.

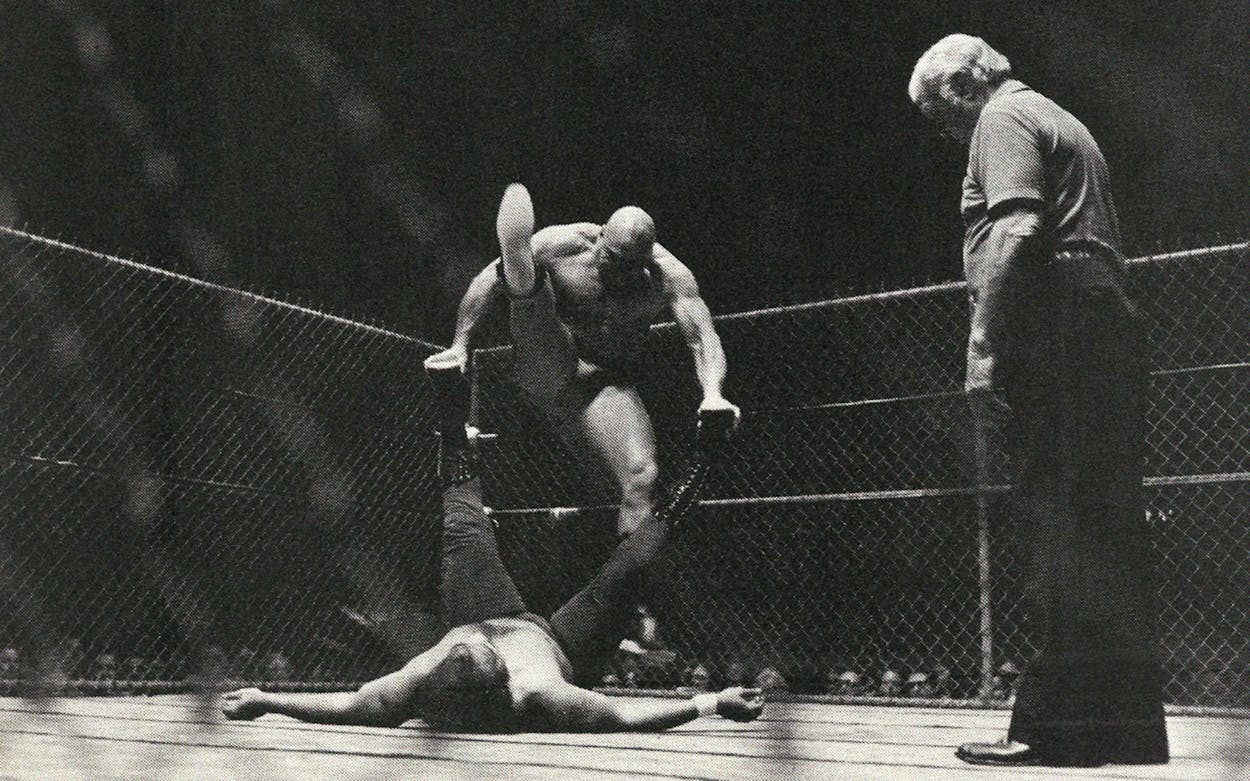

For the main event, a chain-link fence was erected around the ring. This was to prevent James J. Dillon from jumping into the ring to work any of his skulduggery. The match was a Texas death match with no time limit or number of falls. The last man to answer the bell would be the winner. Lothario and the Stomper traded falls back and forth for a while. The Stomper stomped Lothario, who lost that fall but managed to recover just in time to answer the bell. He responded then with a claw hold on the Stomper’s stomach that had the Mongolian writhing in pain. Eventually Lothario tore off the Stomper’s boot and began beating him with it on the top of his shaved skull. The Stomper then gave himself a blade job, and from the amount of blood that poured from his forehead it seemed that Lothario must have split open his head. The Stomper collapsed in the middle of the ring and Lothario fell on top of him. Dillon, able to contain himself no longer, tried to climb over the fence to help his fighter, but Lothario saw him coming, leapt up the fence, and smashed Dillon in the face. The fans were in a frenzy; their cheering reached a sudden peak when they saw Dillon’s cigar fly from his mouth and his head snap back from the force of Lothario’s blow. Lothario was about to beat on Dillon some more when the Stomper, whom everyone had forgotten in the excitement, revived himself, snuck up behind Lothario, and whapped him on the back of the head with his boot. That was the final blow. Lothario collapsed, not to recover until the match was over.

I walked down to ringside with Karl following reluctantly behind. A tall man with a slick, black ducktail and long sideburns was berating a small group of fans. “There’s got to be a rematch,” he shouted. “Dillon can’t climb up that fence. He can’t touch that fence. And the goddamn referee’s so stupid he didn’t even see it. Let me get in that ring with Dillon. Hell, I was in Viet Nam, I’ll go in against the Stomper. If the goddamn referee’ll keep his eyes open.”

The crowd around him seemed to be in agreement. I didn’t doubt that when the rematch came, as it must, the crowd would be as big as it was tonight. “All a wrestling match is,” Karl had told me earlier, “is an advertisement for the next match.”

I would have listened to the duck-tailed man longer. It had been a long time since I’d seen a sports fan so worked up about anything. But Karl tugged on my sleeve. “Let’s go,” he said. “I’ve seen too many guys like that in my life already.”

I left then, but I found myself wondering whether, just when the Stomper was about to stomp, you couldn’t twist around suddenly, catch him in a reverse scissor lock, then. . . and it was that reverie, after I’d dropped Karl off, that kept me company all the way home.

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Port Arthur

- Houston