This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

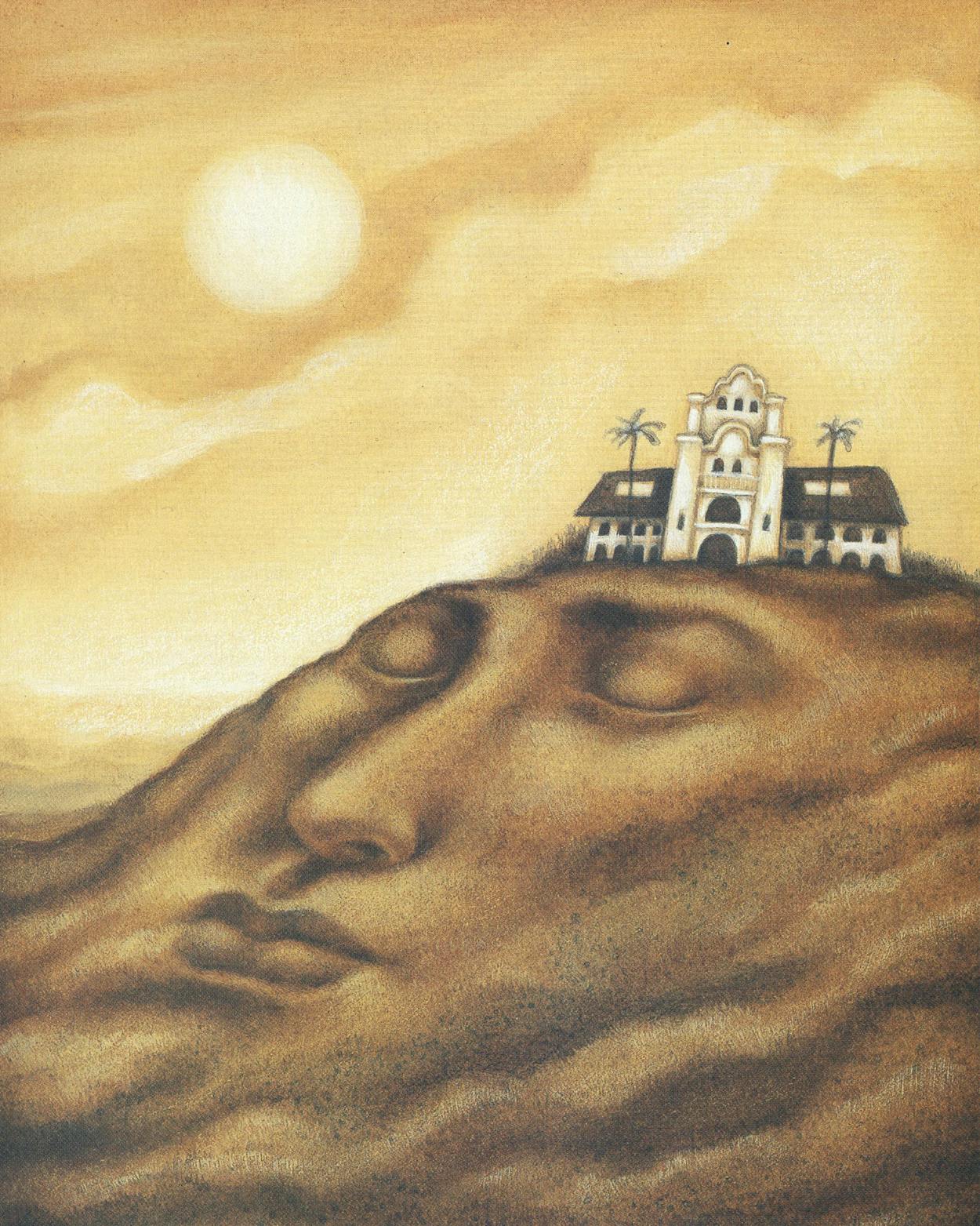

When Sarita Kenedy East was in her sixties, she used to climb into the tower of her three-story ranch mansion and sit for hours alone. All she saw in every direction belonged to her. She would drink Scotch and ask God why she—La Patrona, the Great Lady of South Texas—was barren and old, with no children to inherit her half of the family’s vast 400,000-acre kingdom.

Now, forty years later, I sit in Sarita’s tower, without benefit of Scotch, listening. Five miles to the east—past the cool grove of palm trees, past the Kenedy family cemetery, farther than the eye can see beyond the flat brush country of South Texas—lies Baffin Bay, an inlet of the Gulf of Mexico. Up in the tower the ocean breeze roars, drowning out the silence that I have come for.

Sarita’s cream-colored mansion is today a house of silent prayer, owned by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a worldwide Catholic order. At any given time up to 25 guests stay here, either beneath the red-tiled roof of the big house or in one of the individual dwellings spread out over the 1,110 acres owned by the Oblates. The name they gave this part of the ranch is Lebh Shomea, which means “listening heart” in Hebrew. I have come for four days, but others have different needs. Some guests stay for only a day. Others remain as long as a year. There are two permanent hermits living in cottages on the property, and it is the hermits’ tradition of reclusive contemplation that defines Lebh Shomea. The cost is moderate (roughly $25 a day for a short stay, including meals), and there is no imposed structure or schedule—only the freedom to hear what silence has to say.

For a time, after the Oblates received the property in 1961, the monks considered putting Lebh Shomea to some active use, such as a center for the treatment of alcoholics or a retreat for troubled marriages. Mercifully, its isolated location—seventy miles south of Corpus Christi, just off U.S. 77, far from the big cities of Texas—saved it from such busy productivity. Silence, the Oblates decided, was the only thing the place was really good for.

Not everyone would find Lebh Shomea to his liking. People of all faiths are welcome, but the very air breathes orthodox Christianity. The place exists for guests to make some kind of connection to the divine; a desire for such a connection is a prerequisite for staying here. Vegetarians might soon be grumpy because twice a day—at lunch and dinner—range-fed beef dominates the table. Lebh Shomea is an odd and stark place to go, but to me it is a second home. Some people escape their troubles at baseball games, health spas, or Wild Man weekends that promise emotional rebirth, but when I can no longer hear myself think, I come to Lebh Shomea. I come to read, to rest, to walk in the wilderness, but most of all, for the simple intuition of truth.

Like any good home, Lebh Shomea is bound by duty to take in those who approach with a sincere heart. To visit, you simply call and tell the priest or one of the nuns who work there when you want to come. If there is room, they will enter your name on the books and give you instructions on how to get the key to the ranch gate, reminding you how easy it is to miss the small town of Sarita.

Though Sarita Kenedy East has been dead for thirty years, her memory is still fresh among residents of her namesake town. On the afternoon of my last visit to Lebh Shomea I stopped by the Kenedy County courthouse in Sarita to admire the wildflowers, and I quickly struck up a conversation with a local woman. “Sarita loved wildflowers,” she explained. “That’s why these are here.”

At the Buckhorn, an isolated gasoline station and store outside Sarita that marks the entry to the Oblates’ property, I told the clerk my name. After scanning the ledger, she handed over the gate key. I drove onto the ranch and switched off the car radio, allowing the silence to begin. It is two miles to the big house—past well-tended fenced pastures filled with browsing exotic game such as nilgai, large blue-gray Indian antelopes that look like short-necked giraffes. No one was waiting to meet me at the Spanish-style house, but I was relieved to find my usual note attached to the dining room bulletin board. Guests come and go in silence here.

This consistency and sense of permanence at Lebh Shomea provide their own comfort. Just as the kitchen is always clean and warm, the tile floors in the big house are always clean and cold. The rooms are small and private, each with a white-covered bed, a crucifix on the wall, and windows that open onto the ranch. The note contained my room assignment, and on the desk in the room was the usual black folder with its imposing guidelines, called the Rule of Life. The pamphlet eliminates the need for spoken questions. Besides explaining the daily routine, it has a map of the ranch and directions to a labyrinth of walking paths. The bicycles are in the garage, and “persons weighing under 200 pounds are welcome to use them.” The Eucharist is celebrated each morning in the chapel; guests are invited to participate. It is the only time of day one is certain to hear another person talk. “In keeping with the spirit of simplicity, makeup and jewelry (except watches and symbols of commitment) are discouraged,” suggests the leaflet.

What does a person do all day long at a place of silence? Pray, for one thing, but not in the usual talkative way. My days at Lebh Shomea are bracketed by two hour-long periods of silent listening, one in the morning and the other in the evening. As simple as it sounds, there is much to learn and hear if you just take the time. Silence can be both busy and noisy.

On a typical day, I walk as much as fifteen miles through dense oak motts and across plains of salt grass, and I am constantly distracted by the sound of turkeys, javelinas, lizards, turtles, and the occasional snake moving across the ground. I also read. The first floor of Sarita’s big house has been converted to a library, with vast and specialized sections on Eastern and Western mysticism. It’s easy to lose track of time in the library but almost impossible to shake the immutability of the place.

Once I pulled a stack of books from a shelf and found a large deer head peering back at me—a hidden trophy that had once belonged to Sarita’s grandfather.

The priest and three nuns at Lebh Shomea don’t allow the silence to keep them from leading active, productive lives. They keep the place going, offer spiritual direction to those who seek it, write books (Father Kelly Nemeck and Sister Marie Coombs have co-authored five books on contemplation, with two more on the way), and manage their land in a self-sufficient manner. In that respect, they are following the work ethic of the medieval Benedictines, who transformed the forests of Scotland and England into productive farm fields, or the Cistercian monks of France, who learned new ways to use water power because they built their monasteries near rivers and streams.

One of the benefits of shared silence is fellowship. If I meet another guest on a walking trail, we greet each other with a nod and keep going. I never feel awkward in my muteness, the way I do in the outside world, for instance, when sharing an elevator with a stranger. People who come to Lebh Shomea choose to be quiet, and therefore it is liberating, not oppressive. No one talks at mealtime, but lunch and dinner are social gatherings nonetheless. The food is placed on a large rectangular table in the center of the basement dining room. Guests pick up what they want and eat at one of the round tables. Nothing is said, but much is communicated. People smile. People frown. Some look calm. Some look as if they are going to jump out of their skin. The silence awakens all five senses and stimulates hunger. We all eat like ravenous ranch hands.

What Lebh Shomea offers is the opposite of the stir created by noisy television evangelists who prey on fear, haggle for money, and create widespread confusion and morbid obsessions. It is different, too, from the mood of mainstream churches, where even in the best of conditions a certain level of confusion is present. I come here to escape my own church, where my husband—not some draconian huckster—is the minister. At church I often find myself trapped in the troubling gap between words and actions; we talk one way and behave another. Here, at least, nobody talks.

Lebh Shomea came into being in June 1973, twelve years after the death of Sarita Kenedy East. Her grandfather Mifflin Kenedy had been a friend and partner of Richard King, the founder of the King Ranch. Together the two men ran a shipping fleet out of Brownsville and established two immense ranches adjacent to each other. Kenedy’s holdings were passed intact to Sarita’s father in 1895, and after the death of her parents, they were divided between Sarita and her brother. A devout Catholic, Sarita revised her will so that upon her death the bishop of Corpus Christi would be the sole trustee of a charitable foundation that controlled the bulk of her estate, but there were complications. In her later years, Sarita had taken as her spiritual adviser a Trappist monk named Brother Leo Gregory, and he claimed that she had instructed him on her deathbed to use her money to help the poor of Latin America. When Brother Leo produced a signed statement from Sarita designating him as the only member of the foundation board, one of Sarita’s relatives filed suit, claiming Brother Leo had exercised undue influence over Sarita. Later the bishop and others joined in the suit against the monk.

Bishop Mariano Garriga, who presided over the Corpus Christi diocese, was so angry over the possibility of losing the booty of a lifetime that he didn’t even give Sarita a decent funeral oration. At her own ranch chapel, he said she had abandoned her relatives and her beloved Texas. Later, others suggested that the young monk might have been the old woman’s lover. The legal battle dragged on for 25 years.

In the end, in 1987, a subsequent bishop and the foundation won out over Brother Leo in court, and now the foundation controls the bulk of Sarita’s $500 million fortune. Brother Leo was dismissed from the Trappists for refusing to settle and went to live in a hermitage in Argentina, where he resides today. The only portion of Sarita’s will that was never contested was the acreage given to the Oblates for a house of prayer. In the late eighties the foundation tried to buy the Oblates’ property, but Sarita’s will forbade the sale. Today Lebh Shomea stands as a refuge in the battle. The events also inspired two books, If You Love Me You Will Do My Will, by Stephen G. Michaud and Hugh Aynesworth (which casts the monk as a villain), and The Kingdom, by George Getschow (scheduled to be released next spring and expected to portray Brother Leo as a victim).

Sitting in Sarita’s tower, staring down at her grave, I found it hard to believe the feudal queen of so great a ranch—rich in cattle and oil as well as myth and memory—might have been charmed out of her land. Sarita may have been melancholy in her old age, but she was still tied to her principal sources of strength, this ranch and the Catholic faith. Who knows what she and Brother Leo meant to each other? In the tower, the only certain thing is that all of us here are Sarita’s heirs.

My family and friends find it comical to picture me at a place of silence. I am a talker. My husband accuses me of finishing his sentences. My colleagues know I regard silence as the primary enemy of any group meeting, and they laughed out loud when I announced that I was going to spend four days without speaking. But part of me is exhausted by words. I know it is time to be quiet when I am driving down the street and become enraged at the sight of billboards—enormous words scrawled on huge signs that mean nothing. Or when I am listening to the news on television and the anchorman uses a special word in a profane way (“the mother of all battles”), and I don’t feel angry at all. Just numb.

The first time it occurred to me that silence might have practical uses was in the summer of 1984 on a trip to Japan. One day I visited a Zen monastery in Hiroshima. Groups of monks took turns raking white rocks in a certain pattern, silently praying that the world might never again witness the explosion of an atomic bomb. Standing in the prayer garden, less than a mile from ground zero, I had an irrational thought: What if the real reason we have not blown ourselves up isn’t the billions of dollars spent on defense since World War II? What if the real reason we are alive is because funny-looking guys are silently raking rocks, far from the centers of world power? Nah, I thought—but then again, a little rock raking couldn’t hurt.

Silence takes some getting used to, but it teaches new ways to hear and speak. I suppose this place is called the Listening Heart because listening is the main way people seek new information. Without the silent step of listening, language dies. In the tower, the clamor of memory, like the roar of the wind, is both an enemy and a friend. Even here the memories of other people’s voices—some good, some bad—persist. I gently dismiss them.

The sky is the color of flamingos now, fiery pink streaked with darkness. Soon the sun will be down. From the tower, the world looks fragile and beautiful. The fragments of my life—family, church, work—seem connected to the totality of creation. I think about how Sarita’s barrenness has born fruit in my own life. This movement—from nothing to something—is the distance that must be traveled internally, and it must be done alone, in silent places. I toast Sarita with a large glass of imaginary Scotch.

The next morning I awake to the chatter of orioles outside my window. It’s time to go home, and the noisy part of me is restless, ready to leave. At the Buckhorn I pause to return the gate key to the clerk, but before I’m out the door, a sweaty laborer stops me and starts speaking in Spanish. His speech is so rapid that I fail to catch the meaning of even a few of his words, but then I stop and listen to him with my heart. The calmer I become, the slower he speaks. Finally, I figure out that he is asking me what kind of money is required to make a telephone call. He digs a handful of coins from his pocket, and I pick out a quarter. We walk to the telephone booth, and I deposit the money. Together we listen for the coin to drop.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Corpus Christi