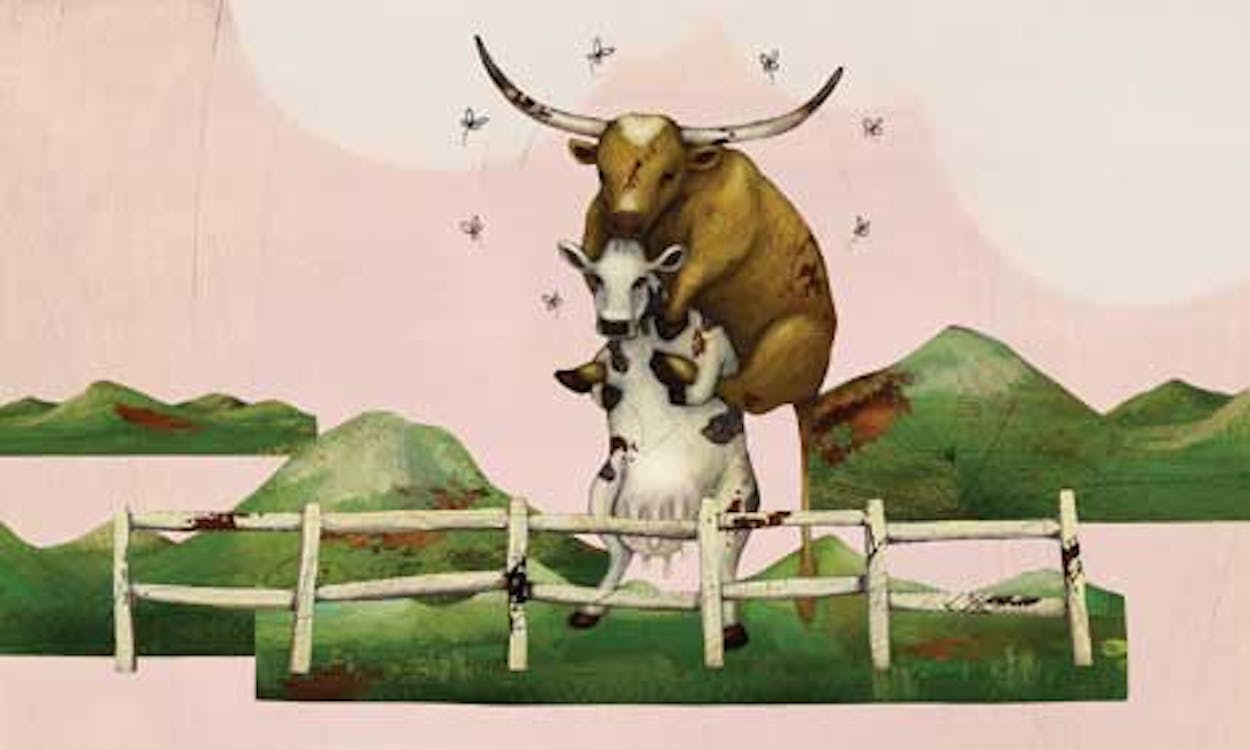

Once upon a time my family was traveling home from our summer camping escapades when my little sister, age four, pointed at a farmer’s field, chirping merrily from the way back of the station wagon: “Why are those cows riding piggyback?”

The resulting cringe from me and my three brothers, our grandmother, and our father did nothing to dampen our mother’s earnest enthusiasm to enlighten. Over the seats my sister came crawling, from way back to front, where our mother whispered feverishly into her ear while the rest of us broiled uncomfortably, trapped in the car, suddenly far too aware of our bodies, our intimate kinship, our grandmother, who’d given birth to our mother, who’d given birth to us, and both of whom must have had sex in order to do so. We tried not to touch, we studied our feet, my father turned up the radio. And still there were those cows, out in their field, some of them blamelessly chewing grass but others having intercourse in full view of the highway. “Oh!” my little sister finally said, frowning, red and infuriated, launched into the same yucky muck as everyone else in the car.

So go many sex education moments. The cringe, the embarrassment, the explanations that don’t ever quite cover the entire mystery. “Why?” my fourth-grade class asked our reluctant teacher, when she explained what went where and how it happened and the perils/miracles that would ensue. Our faces said, “Ewww!” Why would anyone want to do such a thing? The science we understood; the mechanics were clear. It was the desire that eluded us. Why, you’d have to be crazy to agree to that stuff! Our dissatisfaction left the teacher tongue-tied, depleted.

“You be the boy,” my cousin commanded, when we were twelve and thirteen. That meant I was on top, at my grandmother’s house, where we were spending the night. We lay that way for a while, listening to the summer crickets out the window, and then she took her turn being the boy. That was as much as we knew: The boy was on top. Over the years, I figured out the rest, one wrestling match after another, one fumbling opponent/boyfriend at a time. I was a Girl Scout in the wilderness, sure that I could make a fire if I found the proper objects to rub together. By the time I got to college, combustion had been accomplished. What I didn’t figure out by trial and error I learned from books. My father had a large library of pornography; I was an avid reader.

Since I was a kid, though, it seems that parenting has been reinvented. My generation of mothers tends to explain everything, and for good reason. It’s dangerous out there; our kids need to be better armed than we were. I pledged early on that I would be a more frank communicator, that I wouldn’t allow any cringing or shame into my relations with my children. And still the gaps, still the inexplicable.

When I was nine months pregnant with my second child, a boy, his three-year-old sister suddenly had a thought. She interrupted our storytelling session on the couch to scowl at my belly. “How’s he gonna get outta there?”

“Well . . .” said I.

“From your mouth?” she asked, making a horrified face. And I was tempted to tell her, Oh, it’s far worse than that! I explained in the same calm tone of voice that my mother must have used with my sister, concerning the cows, just what was what. Her furrowed brow said she didn’t believe it; if I hadn’t already been through it once before, I might not have believed it either. Instinctively, she seemed to know that she didn’t yet want to find out how he’d gotten in there, and so didn’t ask. And though I would have been happy to explain the process, the much less clear piece of the equation dates back to her father’s and my courtship. Back when our children were not even what some euphemistic winking type might call “a twinkle in their father’s eye.”

The twinkle is the problem, isn’t it? How much simpler to be delivered by a stork or found in a cabbage patch or sent by God.

Later, when my daughter was seven and her brother four, their then babysitter brought them home one day in a maniacal bluster. She’d turned them loose at a park in our little city in New Mexico, and they’d found what they thought were balloons. Before she could get to them, they’d filled the “balloons” with water. They’d thrown the “balloons” at each other. They’d even been putting the “balloons” in their mouths to drink the water.

I rushed my daughter to the bathtub (why?) while she sobbed and sobbed. The babysitter had provided half-information to the children on the ride home, managing to work everybody into a fever pitch. I phoned the hospital, where an amused doctor in the ER told me I didn’t need to worry about AIDS, that the virus would have been killed within seconds of a condom’s being discarded. This fear allayed, I quizzed my traumatized daughter, discovering as we both calmed down that the “balloons” had been in a box, unused; she and her brother had merely filled them at the drinking fountain and tossed them harmlessly around. The nightmare had begun when their babysitter finally caught up; it was her panic that set them off.

“What’s a condom?” my son asked, maybe two years after that, in the middle of a Seinfeld episode where a vividly colored one figured in the plot, Kramer bursting through the door, Elaine shoving Jerry in the chest, George holding some small blue object in his hand, delighted to learn that his “boys can swim.”

“Lalalalalalalalala!” exclaimed our daughter adamantly, the older sister, plugging her ears and dashing out of the room. Patiently, my husband and I explained, in that saccharine birds-and-bees voice that everyone knows so well. When a mommy loves a daddy very much . . . (When a cow loves a bull . . .)

Our son took in this new information, sighed, duly notified, then yelled to his sister, “You can come back now.”

“Sponge-worthy” showed up on a subsequent Seinfeld episode; similar questions arose, similar explanations were given.

Eventually, the conversation had to take a different tone. When my daughter began to go through puberty, she came to me concerned about the changes in her body. It was an anxiety I remembered from my own adolescence. I had confided in no one, stolen my first bra from my best friend rather than confess I needed one to my mother. So I tried to get my daughter to take a different tack. “Of course your body’s going to change,” I said, utterly no-nonsense. Did she really want to be the first female who didn’t grow breasts? Underarm hair? That would be the freakish thing, not changing. Friends were having menstruation parties for their daughters; Kansan that I am, I found that a little too California-crunchy-granola for us. Instead, I taught my daughter how to shave her legs (I still have a scar from my own do-it-yourself, trial-by-fire days) and how to use hydrogen peroxide to remove blood stains. We discussed STDs. At school one of her teachers demonstrated rolling a rubber over a banana (when I was a kid, we’d done this in a friend’s basement, and we’d used a cucumber, which probably led to a few disappointments later on).

When it was my son’s turn, we went to Target and did some shopping. Into the cart went a variety of supplies: dandruff shampoo, deodorant (did he really want to be the boy with BO in his class?), razors, and a giant box of condoms. At checkout, as he pulled these and all manner of other products from our cart onto the conveyor belt, he observed that we were going to be ready for anything. The woman at the cash register gave us a dubious glance.

(Sometimes I check in on the box of condoms, stored in my son’s bathroom medicine cabinet. They are disappearing, but then his high school mascot is a Trojan, and at football games the students toss the foil-wrapped packets at the opposition.)

The woman at the cash register might have been right—you can’t really be ready for every single anything, no matter how well stocked your cupboard, no matter how good your intentions, how astute your memory, how vivid your imagination. You can cite information about hormones and eggs and spermatozoa and pheromones and even bring in the animals—those penguins and cranes and wolves and monkeys, all gaga with instinct and some touchingly anthropomorphized traits, like monogamy or compassion or fidelity—but nothing can explain the insanity of lust and attraction and passion, the random firing of the brain’s pleasure center.

And what about love? As a teacher of creative writing, I’ve had to instruct students for more than twenty years how not to use words to describe the object of love—not to note the auburn tresses or spectacular pectorals, the Windex-blue eyes or the Jell-O-like breasts—but rather to focus on the unnameable, the ineffable, the incredible sensation of dignified love, that strange enchantment two people concoct in contact with each other. Spiritually. Bodily. Fantastically. This force is naked to the human eye, I tell them; its parts do not add up to its sum. It’s a condition, an illness, the vapors, cancer. “What’s wrong with her?” “She’s in love.” Enough said.

But the hardest word to define, even (especially?) to ourselves, may be the one we toss blithely, helplessly around all the time: desire. And not just hard to define, but impossible to regulate. All over the place, adults are trying, using a word like “abstinence” as arsenal. But what is abstinence when pitted against an incendiary glance? You can teach the head; you’ll never teach the heart. There are far too many examples of grown-ups who prove this lesson; we read about their peccadilloes every day in the newspaper. So what makes us think our kids are going to be any better at reining themselves in than we, their elders, are? My son’s girlfriend’s mother dropped by to meet me one day; she wanted to be sure there was an adult in the house. I think my son’s facial hair scares her. We shook hands, I promised her my son’s intentions were honorable. He later thanked me for not mentioning the little trip he and I had taken to Victoria’s Secret to get his girl a birthday gift. I had discouraged the racier version of a camisole he’d first selected, the transparent one with slits everywhere, in favor of the more decorous floral model. Still, we couldn’t avoid also acquiring a thong, as one came with every set. At checkout, he picked up a bottle of pink, cherry-flavored massage oil from the impulse-buy rack. “Better than coconut,” I agreed.

The other mother-son duo in the place was a six-year-old with his face buried in his mother’s skirt. “Can we go?” he was pleading, exposed to all the stuff he so didn’t want to know about. Yet.

One day it’ll hit that kid like a bolt from the blue, as if somebody had flipped a switch or cast a spell, voodooed him. He’ll be turned on, tuned in, raring to go. Concerning desire, that twinkle in the eye, that sudden racing heartbeat and chill up the spine, the insomnia and misery of wanting and needing the other, that certain alluring someone who becomes the center of your spinning universe, you might as well simply shrug in defeat, confess to your children, “I don’t know. It’s magic.” They do, after all, understand that.