On Sunday morning, October 17, 2010, Kay Baby Epperson packed three large suitcases full of clothes and a smaller one containing her best makeup. The seventy-year-old retired hairdresser then asked her husband, Gary, to carry her luggage to her Lincoln Continental, which was parked in the carport next to their home in the small East Texas town of Rusk.

“Goodbye, honey,” Kay Baby said as she climbed behind the wheel. “I’m off to do my movie.”

She was dressed in her favorite red blouse with sparkly red rhinestones, a pair of pressed blue jeans, and boots. She wore diamond rings on six of her fingers, and a piece of crystal from a bathroom chandelier at Elvis’s Graceland mansion hung from her neck.

Gary, a lanky man who wore a rebel flag gimme cap, looked suspiciously at his wife. “Now, Kay Baby, you sure you’re not going to Las Vegas?” he asked. “To gamble away all our money?”

“Oh, for Pete’s sake,” Kay Baby said, giving herself a quick once-over in the rearview mirror and fluffing up her blond hair, which she had been bleaching for forty years. She lit a Kent cigarette and leaned her head out the window. “And Gary, please feed the cats while I’m gone.”

Kay Baby was headed to Bastrop, thirty miles east of Austin, where filming was about to begin for Bernie, a movie based on the peculiar story of Bernie Tiede. A beloved former assistant director of a funeral home in the East Texas town of Carthage, the 39-year-old was arrested in 1997 for the murder of 81-year-old Marjorie Nugent, the sour-tempered widow of a rich local oilman. Bernie had become Mrs. Nugent’s ever-present companion and the sole heir to her estate, but he freely admitted to police that he had shot her four times in the back and stuffed her in a deep freeze in her home, where she had remained for nine months before police discovered her. He explained that he felt he had to shoot Mrs. Nugent because she had become “very hateful and very possessive.”

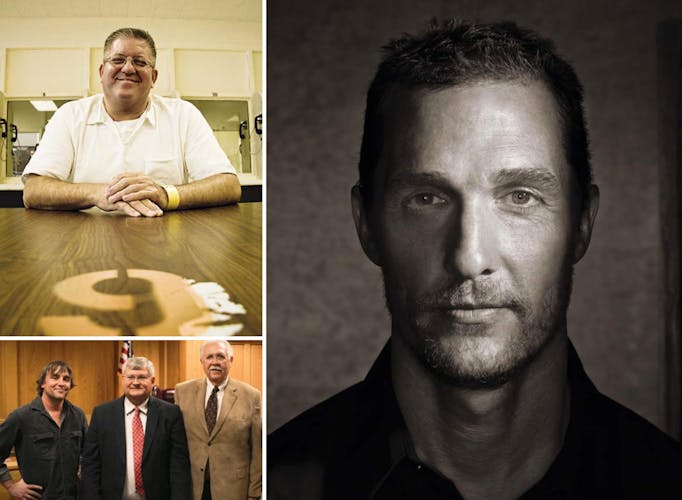

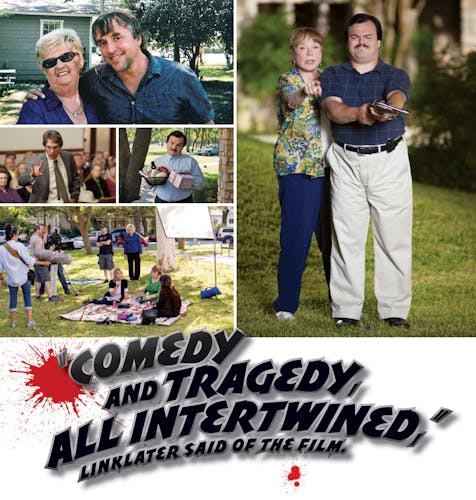

Almost from the moment he had heard about the case, Richard Linklater had wanted to make a movie about the story. Finally, after years of delays, he had secured funding and persuaded three of Hollywood’s biggest names to star in the film: Jack Black to play Bernie, Shirley MacLaine to take on the role of Mrs. Nugent, and Matthew McConaughey to portray Danny Buck Davidson, the criminal district attorney who prosecuted the case. Linklater also hired a number of small-town East Texans, only a couple of whom had any acting experience, to play the townspeople of Carthage. In addition to Kay Baby, he had picked real-life housewives, oil field workers, a waitress at a cafe, a part-time country music singer, and a pest exterminator. And he told all of them to be in Bastrop by October 17, where his production team—technicians, caterers, stylists, wardrobe artists, and crew members—was already gathered, preparing to re-create the series of events that led to Mrs. Nugent’s murder.

Kay Baby was so excited she was already practicing her lines in her rearview mirror as she pulled out of her driveway, making sure her facial expressions were just right. About five minutes outside of Rusk, however, she crested a hill and slammed her Lincoln into a car driven by, she later told me, “an illegal Spanish boy with no insurance talking on his cellphone.”

When paramedics arrived, she was dazed, her breathing labored, her hands clutching her chest in pain. But she refused to go to the hospital. She called Gary, who called his sister, who said she had no errands to run that day and would be happy to drive Kay Baby to Bastrop.

“Honey, this is my moment, and at my age, I don’t get too many moments,” Kay Baby told me after she arrived at Bastrop’s Hampton Inn, where all the East Texans were staying. She lit a Kent and waved it in the air. “Do you really think I’d miss this? As far as I’m concerned, Bernie could be the next Gone With the Wind.”

One day after the news broke in August 1997 about Bernie’s arrest, I threw my reporter’s notebook into my car and dashed off to Carthage. It seemed impossible to me that any of this had actually happened. Bernie stood to inherit millions from Mrs. Nugent, but he went ahead and shot her anyway. Then, instead of getting rid of Mrs. Nugent’s body, the mortician placed her in her own deep freeze because, he later said, he eventually wanted to give her a proper burial. And what was most mind-boggling was that no one, not even Mrs. Nugent’s relatives, noticed that she had dropped out of sight. During those nine months, Bernie became a kind of Robin Hood, using her money to give to people in need throughout Carthage.

I could not imagine the story getting any stranger, until I visited Daddy Sam’s BBQ and Catfish (“You Kill It, I’ll Cook It”), one of Carthage’s most popular restaurants. There, I watched a group of people walk right up to the bulldog-faced Danny Buck and beg him to drop charges against Bernie—or at least give the poor man probation. “Ol’ Bernie’s a back shooter!” he told me between bites of slaw. “But people here just want the whole thing to go away.”

In fact, everywhere I went, I listened to residents describe Bernie as the kindest, most generous person they had ever known. I drove over to the county jail, where some of Bernie’s supporters had written “Free Bernie” with shoe polish on the windows of their cars and driven back and forth in front of the building to let him know they cared. When I went to the funeral home where Bernie had worked, just a block away from the jail, his boss went on and on about the beautiful funerals Bernie staged, sending off everyone in Carthage, including the town’s drunks, in high style.

Then, a few days after my article, “Midnight in the Garden of East Texas,” was published in the January 1998 issue of Texas Monthly, my phone rang. The voice on the other end identified himself as Rick Linklater. He told me he wanted to make a movie about Bernie and he wanted me to help him write the screenplay.

For several seconds, I had no idea what to say. I knew all about Linklater, of course. At the time, he was being hailed, in the words of the Los Angeles Times, as “the filmmaking voice of a generation.” Three low-budget films he had written and directed in the nineties—Slacker, Dazed and Confused, and Before Sunrise—were regarded by critics as minor masterpieces, and Hollywood studios were clamoring for him, hoping he would work his magic on their projects.

I, on the other hand, had never written a screenplay. Nor could I imagine why Linklater would be remotely interested in making a movie about a quirky murder set in East Texas. “Is this a prank call?” I asked.

“Absolutely not,” he said. “Come on, let’s get together one day when you’re free and talk about it.”

And so I found myself driving from my quiet North Dallas home to his trendy downtown Austin loft for our first meeting. When he opened the front door, he was barefoot, dressed only in cutoff shorts and a gray Shonen Knife T-shirt with a teddy bear’s head on the front (Shonen Knife, I would learn after an Internet search, is a female Japanese punk band). The 37-year-old had a short goatee, and his brown hair was mostly unbrushed, falling over his eyes and hanging below his ears. He looked maybe half his age. “Hey, man, come on in,” he said, giving me a congenial grin.

I looked around his loft, the walls of which were full of movie posters for foreign films I’d never heard of and couldn’t quite pronounce: Buñuel’s Los olvidados, Antonioni’s Il deserto rosso, Godard’s Masculin féminin, Bresson’s Lancelot du lac, and so on. Then Linklater picked up a Nerf football. “So, let’s talk about Bernie,” he said as he walked to one end of the loft, about fifty feet away. He turned around and fired a perfect spiral right at me. I was so discombobulated that the football zipped right through my hands, hit a chair, and bounced off one of the posters.

Linklater, I was about to learn, is a peculiar combination of art-house auteur and all-American boy. Born in Houston and raised in Huntsville, he was a star athlete in high school. As the shortstop on his baseball team, his batting average topped .400, and as the quarterback on the football team, he once set a record for the longest touchdown run in school history. After graduation, he attended Sam Houston State University to play baseball, but he was forced to leave the team during his sophomore year after developing an arrhythmia. Eventually, he dropped out of college, moved to Houston, and went to work on an offshore oil rig, seemingly destined for a life of blue-collar obscurity.

But as far back as elementary school, Linklater told me, he would retreat into his bedroom to read, write short stories, listen to music, and stare out his window—“just imagining another world altogether, some kind of fantasy world,” he said. When he was working on the rig, he spent his days off watching hundreds of movies, everything from action flicks to French new wave cinema. He also read voraciously: novels, poetry, essays, and film criticism. Then, in 1983, he used part of his earnings to buy a Super 8 camera and editing equipment, and he moved to Austin to make movies.

His first film was Frisbee Golf: The Movie. It was twelve minutes long and did not suggest the presence of a cinematic genius. Several years later, after maxing out his credit cards and begging relatives for loans, he scrounged up $23,000 to make a movie called Slacker, about a day in the life of a random collection of Austin bohemians. He had them wander in and out of scenes as they discussed, at length, a variety of offbeat, quasi-intellectual ideas. Slacker became a surprise hit when it was released, during the summer of 1991, and before long it slipped into the national consciousness. The term “slacker” became a catchall to describe a young person who had no interest in pursuing a career. Two years later, Linklater made Dazed and Confused, which followed a group of Texas teenagers on the last day of high school in 1976 and featured Matthew McConaughey in his breakout role. Critics ate it up, comparing the movie to George Lucas’s American Graffiti. Then came 1995’s Before Sunrise—this one about two strangers who spend a night walking around Vienna—which the critic for the English newspaper the Guardian named the third-best romantic film of all time.

His success brought him offers from major studios, including the big-budget remake of the prison football movie The Longest Yard. But he told me that what he really wanted to do was make a film about the kind of people he had known growing up in East Texas. “And when I read about Bernie, Mrs. Nugent, and everyone else in Carthage, I knew this was it,” he said.

Not long after we met, we drove in Linklater’s pickup to the town of San Augustine, south of Carthage, to watch Bernie’s murder trial. (The judge had moved the proceedings after Danny Buck had convinced him that there weren’t enough jurors in Carthage who’d be willing to convict Bernie.) On the courthouse lawn, Linklater talked to some Carthage townspeople who had brought along baked goods that they hoped the bailiffs would pass on to Bernie in his time of need. During the trial itself, he couldn’t take his eyes off Bernie when he testified about the desperation that he felt before he shot Mrs. Nugent. Then Bernie was found guilty and given a life sentence. “We love you, Bernie,” his supporters yelled as he was escorted out of the courthouse, a tormented look on his face.

Linklater was awestruck. “Comedy and tragedy, all intertwined,” he said, shaking his head as we drove away.

We finished the screenplay within seven months. Or, I should say, Linklater did. He essentially put the whole thing together, while I contributed some plot points and dialogue. I also wrote several made-up scenes that I thought were hilarious but Linklater didn’t even consider using. In one, I had the driver of the hearse at Bernie’s funeral home listening to a baseball game on the radio and spitting tobacco juice out the window as he led a funeral procession to the cemetery. He had forgotten to lock the rear door, and when he hit a bump, it flew open and the casket fell out, which was promptly run over by the cars following the hearse. I roared with laughter when I told Linklater what I’d written, but he just gave me a gentle smile, perhaps trying to hide his alarm that I was turning into Adam Sandler. “We really don’t have to push the comic boundaries here,” he said in a quiet voice. “The real story alone is interesting enough.”

In fact, to give the movie an extra dose of authenticity, Linklater came up with the idea of having townspeople interrupt the narrative and speak directly to the camera, spouting unvarnished gossip and reminiscences about Bernie and Mrs. Nugent. “If you live in a small town, you’re often defined by the gossip about you,” he explained. “And with Mrs. Nugent gone and Bernie in jail, all that was left were people talking about what had happened. Everyone had an angle. So the thought hit me that the proper way to tell the story would be from the town’s point of view, a kind of large Greek chorus of gossips.”

A Los Angeles film production company that had paid us to write the screenplay seemed happy with our final draft. But as so often happens in the movie business, the script sat on the shelf for years, and Linklater moved on to other projects. He did a couple of big-budget movies for Hollywood’s major studios, one of which was The School of Rock, a surprise hit featuring a heavy-metal guitarist, played by Jack Black, who gets kicked out of his band and finds a job as a substitute teacher at a prep school. He also made a sequel to Before Sunrise called Before Sunset, which garnered him an Academy Award nomination for best adapted screenplay. Then came a remake of The Bad News Bears; an animated adaptation of a Philip K. Dick novel (A Scanner Darkly); a tale about corruption in the meatpacking business (Fast Food Nation); and a period piece about the American theater (Me and Orson Welles). We touched base every now and again, but I assumed the story of Bernie Tiede was gone forever.

Then, in May 2010, more than a decade after we had finished the screenplay, he called out of the blue. We discussed kids and sports and politics. “Oh, by the way, I’ve been meaning to tell you,” he finally said. “The movie’s back on.”

“What movie?” I asked.

The news that Bernie was being made sent Carthage into a frenzy—and not everyone was happy about it. Some of the town’s leading citizens were worried that the movie would make Carthage look bad and perhaps spell the end of its appearance in the book America’s Top-Rated Small Towns and Cities. A few people even asked Danny Buck if he could keep Linklater out of Carthage. “He’s going to make us out to look like a bunch of hicks!” they said. “Like those people in Deliverance!”

When Linklater announced that he would be holding auditions for “the gossips” in Longview, Texarkana, and Carthage itself, some Carthage pastors suggested to the members of their congregations that they not try out for the movie, because Christians shouldn’t make fun of the dead, even if they didn’t particularly like the person who had died. Aaron Bequette, the pastor of Northside Christian Center, put the phrase “Murder Is Dark, But Not Comedy” on the marquee in front of his church. He told me, “I just don’t understand the idea of taking the murder of an old woman and making it into something funny. It was a horrific tragedy in this town and should be treated as such.”

Linklater explained that he was not trying to belittle Carthage or the crime. In a press release, he declared that he was drawn to the story because it captured “all the hilarity, friendliness, and sometimes strangeness of small-town Texas life.”

Several residents, including Danny Buck, who’s been the criminal district attorney for eighteen years, weren’t appeased. “You know these Hollywood people,” he told me when I called him before filming began. “They think they can do anything they want.”

“On the other hand, Rick’s got Matthew McConaughey playing you,” I said.

“Well, he better do a damn good job,” growled Danny Buck.

Approximately three hundred people auditioned for the movie. Sheila Steele, Linklater’s associate casting director, told the hopefuls who came to Carthage’s Davis Park Community Center that she wanted each of them to tell a story, which she would videotape for Linklater. One woman talked for ten minutes about how she couldn’t get her feet into some new shoes she bought because she forgot to take the paper stuffing out of the toes. Another woman pretended to have a conversation with a teacup about the teacup’s history. An exterminator recalled an incident in which Mrs. Nugent asked him to clean her chimney but sent him on his way when he told her it would cost $50.

Driving in from Rusk for her audition, Kay Baby had a hard time finding the community center, so she eventually called 911 for directions. But once she arrived, she lit a Kent and started gabbing away. She told Steele that she had received her beautician’s degree from the Barrow Beauty School, in Tyler, and then returned to Rusk to open Kay’s Hair Fashions. In 1968, she continued, barely taking a breath, she took a vacation to Las Vegas, where she met members of Elvis Presley’s band. Two years later she met the King himself and began giving all of them haircuts, either in Vegas or whenever they came through Texas. During one visit to Graceland, she plucked a crystal from the chandelier in Elvis’s “shampoo room” and made it into a pendant.

As soon as Linklater saw the tape of her audition, he said, “She’s in.” Kay Baby was so excited when she learned she had been cast that she raced to Houston to buy a $5,000 purple mink coat at Woody’s Furs, which she thought would be perfect to wear in one of the movie’s funeral home scenes.

Besides selecting 21 East Texans, Linklater also hired a couple of ringers to be gossips: Sonny Carl Davis, a veteran screen actor from Austin, and, in a surprise move, McConaughey’s own mother, Kay, who’s known to everyone as Kmac. A striking, silver-haired woman with swimming-pool-blue eyes, she raised Matthew in Longview and now lives in Sun City, the senior community near Georgetown, north of Austin, where she takes Pilates and performs in amateur theatrical productions. “For years, I’ve been begging Matthew to get me a role in one of his movies, but he’s always weaseled out of it, making up some nonsense about not having the power to do it,” she told me recently. “One time when I was visiting him in Los Angeles, I met Brian Grazer, the movie producer, and I said, ‘Hey, don’t you think it would be a great idea if you did a remake of The Graduate with Matthew playing Dustin Hoffman and me playing Anne Bancroft?’ He said, ‘Mrs. McConaughey, do you realize you’d have to do a love scene with your own son?’ And I said, ‘Oh, hell. It’s no big deal. We’ll fake it.’ Can you believe he still said no? Well, thank God for Richard Linklater, who’s finally seen my real potential.”

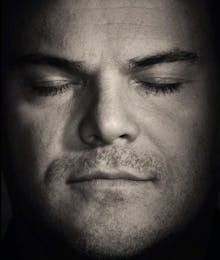

Though the East Texans proved to be authentic as East Texans, Black needed a bit of help to master his role. To make sure Black captured Bernie’s soft-voweled lilt, Linklater took him to the prison in Beeville, where Bernie was incarcerated. (As soon as Black walked into the prison, the Hispanic inmates began shouting, “Nacho Libre!”; the white inmates, in turn, yelled, “School of Rock!”) Bernie, who had been in prison for twelve years, was waiting for Black and Linklater in the visiting room, his hair immaculately combed and his white prison uniform neatly pressed. He was as gentlemanly as he had been during his funeral home days, smiling warmly, giving Black a delicate handshake and patting him on the back. He talked about how he passed the time—teaching nutrition and behavior management classes to other inmates and working in the prison craft shop, where he crocheted “memorials” to send to the families of Carthage residents who had died. He also spoke about the remorse he felt for what he had done to Mrs. Nugent. “I didn’t mean to hurt Marjorie,” he said, blinking back tears. “I hope you understand that. There was just a moment when something—I don’t know what—came over me.”

By the end of the visit, Black was talking like Bernie and had acquired his light, mincing walk and his solicitous mannerisms. “It seems as though he’s obsessed with being loved, and I can relate to that,” Black told me later, in a candid admission for a movie star. “I don’t like to have anyone think badly of me, and I understand that sort of obsession with making sure that everything is all good with everyone. His one character flaw is that he never had a release valve. He never got angry at anyone, even if he was mistreated, and over time that buildup led to his snapping. I just thought that was a fascinating thing to play.”

To stay within their tiny $5 million budget, Linklater and his producer Ginger Sledge, a former Austin teacher who had worked her way up in the movie business, planned a tight 22-day shooting schedule in Bastrop. After spending most of the first week filming some of the smaller scenes, Linklater brought the cast together for the first time to shoot the trial. The gossips and other extras (many of them friends or relatives of the gossips) were escorted into the courtroom, and when some of the older women saw Black—portly, mustachioed, and dressed in a black suit—they gasped. He walked over and acted delighted to see them, just as Bernie used to do, and the women gasped again.

Then McConaughey, with his usual cool ease, sauntered into the courtroom. When Linklater first talked to his old buddy about Bernie—the two had been taking batting practice with the University of Texas baseball team—McConaughey thought Linklater was offering him the title role. After reading the script, he was ecstatic, writing Linklater an email about how grateful he was for being given the chance to show his feminine side. “Man, I am in!” McConaughey exclaimed. The director gently explained that the time had not yet come for McConaughey to show his feminine side but that he should instead take on the challenge of Danny Buck Davidson. He also made it clear to McConaughey that he wanted him to look the part of an East Texas district attorney. He had him wear a wig made of limp gray hair, oversized glasses, plumpers in his cheeks, and a weight belt that added an extra twenty pounds to his waist.

Still, McConaughey looked pretty damn good. After the camera and lights were repositioned, Linklater told him, “Okay, let’s try Danny Buck’s speech.” The director was wearing a short-sleeved T-shirt, cargo shorts, and tennis shoes. If you had no idea who he was, you would never guess he was the guy in charge. As he turned to McConaughey, I scooted toward them, hoping to hear some thoughtful discussion between the director and his actor. Instead, McConaughey said, “Why don’t you let me try something here?”

“Okay, whatever, sounds good,” Linklater replied with a casual shrug.

The cameras started rolling, and McConaughey flipped a switch. Pulling at his tie and adjusting his glasses, he stomped across the courtroom and launched into an improvised rant about the murder. “Bring in the freezer, where Mrs. Nugent spent the first nine months of her afterlife!” he shouted at a bailiff. I turned and looked at the people from Carthage. They were hanging on every unscripted word. It was as though the clock had been turned back and they had no idea how the trial was going to turn out.

Then the gossips and the extras were taken to a Bastrop cemetery, where Linklater was preparing to shoot the scene in which Bernie meets Mrs. Nugent at her husband’s graveside service. Shirley MacLaine emerged from her car and headed their way, trailed by her dog, Terry, an elderly rat terrier. Wearing a black dress and a black hat to match her dour mood, she turned and snapped at her assistant. When a couple of bees flew by, she waved her hands in the air and said, “Bastard bees. Bastard bees.”

It was the first time that many of the Carthage residents had seen MacLaine, and once again, they gasped. She strode toward a chair placed in front of the casket, and she peered at all the extras, who continued to watch her intently. A few glanced sympathetically at Black, who was already in character, acting like the portrait of proper grievousness, clasping his hands prayerfully in front of his stomach, his lips pressed together.

“I just can’t get over it, thinking about what that lady did to Bernie,” one of the extras, Reba Tarjick, a 72-year-old Carthage widow, told me as she kept her eye on MacLaine. “He was an angel, God’s gift to Carthage. He sure as tootin’ was. And Mrs. Nugent just made him plumb crazy.”

“Um, Reba, you know that Jack and Shirley are acting, don’t you?” I asked.

“Well, it sure doesn’t feel like it. I can’t even call Jack by his real name. To me, he’s Bernie, and I love him with all my heart.” Then she turned and stared coldly again at MacLaine.

Just to be clear, MacLaine is an extremely charming woman. She often invited me to lunch in her trailer and regaled me with stories about everything from famous Hollywood men who had wanted to sleep with her to her dislike of Debra Winger while they filmed Terms of Endearment to a meeting she had had with President Jimmy Carter, who wanted to hear about her well-publicized theories on reincarnation, past lives, and UFOs. (“I said, ‘Mr. President, the UFOs are telling us that life is a continuum and that our souls move on to other lives.’ He cut me off, saying he couldn’t listen to such talk because he was a Christian.”) During one lunch, she told me the details of the three-year romantic relationship that she’d had in the seventies with New York City journalist Pete Hamill. “I love journalists,” she said, one eyebrow rising, and I felt my legs get wobbly.

Yet as soon as she put on her wardrobe, she became, well, mysteriously churlish. She went after a makeup artist for not touching up her face properly, and she lambasted a crew member for not keeping an umbrella over her head to keep the sun out of her face. Once, while I was in her trailer, hoping to befriend her dog, who had been growling at me, I slipped the animal a bit of my chocolate chip cookie. MacLaine, who was still dressed as Mrs. Nugent, almost flew off her couch. “You dare feed my Terry chocolate?” she screeched. “What is wrong with you?”

She kept looking at me in silence, and I felt a chill. This, I realized, was exactly what Bernie must have felt when Mrs. Nugent criticized him.

One afternoon I introduced MacLaine to Mrs. Nugent’s nephew, a Los Angeles–based freelance writer named Joe Rhodes who had been locked by his aunt in her guest bedroom for two days when he was a child. MacLaine happened to mention that she wouldn’t let anyone touch her while she was filming this movie because she sensed that’s what Mrs. Nugent would have done.

“That’s exactly right,” said Rhodes. “How did you know that? Aunt Marge never let anyone touch her!” He then said that he had noticed MacLaine snacking on peanut-butter-and-cheese crackers during breaks.

“Almost obsessively, and I don’t know why,” she replied.

According to family lore, Rhodes told her, Mrs. Nugent’s father, who owned a general store, had come up with cheddar cheese crackers spread with peanut butter and sold his idea to Toms Candy Company, which put them in vending machines everywhere. “You’re basically eating a snack her father invented,” he said. “Shirley, is it possible you’re channeling my Aunt Marge?”

Oh boy, I thought, here we go. MacLaine is going to throw a fit and toss us out of her trailer. But after a pause, she dramatically raised her hands toward the sky. “Something is happening here,” she said solemnly. “Something is happening.”

During my visits with MacLaine, the subject she wanted to talk about the most was Linklater. The director never raises his voice or gets animated in any way during filming. He never tells his actors to read their lines a certain way. After a take he sometimes says, “Hmm, I don’t know. Maybe. Let’s try it again.”

For MacLaine, who had worked with such controlling directors as Alfred Hitchcock and Billy Wilder, Linklater’s style was simply mystifying. “He does all these retakes, but he doesn’t tell me what’s wrong with the last take,” she told me. “Is he really directing the movie? Does he know what he’s doing? He’s leaving me alone! All alone!”

At one point, she began calling Linklater “Ricky the Boy,” because she said he looked about twenty. Behind his back, she began to pretend to write down notes in an invisible notebook whenever he spoke, telling people she was recording his “words of wisdom.” During one of my trips to her trailer, she was watching The School of Rock, trying to glean some insight into how he worked. “You’ve got to help me,” she said. “I’ve been in this business for fifty-five years, and no director has treated me this way!”

I hunted down Linklater and told him that I suspected MacLaine was having a near breakdown. He shrugged, gave me a serene look, and said, “Oh, she’s fine. It will all work out.”

Throughout the entire shoot, I never once saw Linklater get upset. (“He’s so Buddhist he doesn’t even know he’s Buddhist,” said McConaughey.) He seemed more amused than peeved when the owner of a funeral home near Bastrop decided at the last minute to cancel his agreement to allow filming at his chapel because he had been told by “a reliable source” that the movie was about gay men having “pornographic sex” in a casket.

What’s more, Linklater never acted as if he was under an intense deadline. He regularly allowed his actors to veer away from the script—“just to see if we might capture a moment that maybe we weren’t expecting,” he told me. One day, he asked Larry Jack Dotson, a retired mechanic who was playing the minister at Mr. Nugent’s funeral, to add some Christian phrases to his eulogy. Dotson, his eyes wide, went hog wild, talking about the glories of meeting Jesus and spending eternity in heaven. And when Linklater heard that one of the gossips, James Baker, a retired union representative from Carthage, had written a country song about Bernie and Mrs. Nugent, he asked his crew to find time to film Baker performing the song. “You put her in the freezer and closed down the lid,” Baker sang. “Didn’t even move it, just made sure it was plugged in! Bernie, oh Bernie, what have you done? You killed poor old Mrs. Nugent and didn’t even run.”

In the end, the East Texans did indeed act as if they were in Gone With the Wind. Linklater was so taken by Kay Baby’s theatrical abilities that he spent an evening writing a scene in which she visited Bernie in prison. Thrilled, Kay Baby pulled her cellphone from her purse and called her husband back in Rusk to say she was going to remain in Bastrop for a couple more days.

“Fine with me,” Gary replied. “The way I look at it, we’re saving money because you’re down there at that movie instead of gambling at the casinos.”

The East Texans even worked their magic on MacLaine—at least once. While waiting for a scene to begin in which she was supposed to attend an elderly ladies’ Sunday school class at the Methodist church, she asked the women around her if they were still having sex with their husbands. “No, Ms. MacLaine, my two husbands are dead,” one replied. “But if you must know, I liked doing sex with the number one husband more than I did with the number two.” MacLaine let out a laugh that could be heard from the opposite end of the set.

And then there was the day she told me that her role as Mrs. Nugent “could possibly” rank right up there with her famous previous portrayals of such irascible grande dames as Ouiser Boudreaux in Steel Magnolias and Aurora Greenway in Terms of Endearment.

I beamed, very proud of myself.

“Notice I said the word ‘could,’ ” MacLaine continued, giving me another of her terrifyingly unblinking looks. “The problem is that you didn’t give Mrs. Nugent enough lines. There’s not enough to flesh her out.”

As I was leaving her trailer, I told her I had to go back to Dallas for a few days. “Well, change your plans,” she said, standing in the doorway. “I want you to stay here. I thought you could take me into Austin this weekend for dinner and a movie.”

I tried to explain that I had some family business to handle, but I barely got the words out before she exclaimed, “Nonsense!”

My heart was pounding. I realized again that this is exactly how Bernie must have felt: unable to please Mrs. Nugent, completely trapped, not sure how to escape. “Well, let me see what I can do,” I said. But when Mrs. Nugent—I mean Shirley MacLaine—turned to go back inside the trailer, I ran for my car and drove away, a coward to the end.

Seven months later, in June 2011, Bernie was shown to the public on the opening night of the Los Angeles Film Festival. I bought an elaborately patterned shirt at Nordstrom, which I left stylishly untucked in hopes that I would better blend in with the trendy Los Angeles film crowd. I looked ridiculously overweight, especially when I stood next to McConaughey. Wearing a white cowboy hat, a blue blazer, jeans, and cowboy boots, he walked the red carpet with his luminous fiancée, Camila Alves, a Brazilian former model. She was in a pink dress that was so tight I wanted to shout for joy.

Then Black and MacLaine arrived together, arm in arm. Her red hair short and chic, MacLaine looked radiant. The channeling of Mrs. Nugent had apparently come to an end. She told interviewers that Black was her “third Jack” (the other two being Lemmon and Nicholson) but he might be her favorite. “He’s made me laugh more than the last twenty men I’ve been with put together,” she said. As part of the media questioning, some reporter asked what each of them would be doing later that summer. Black said he would be visiting his father at his farm. Not missing a beat, MacLaine said she too would be visiting her father, who died 25 years ago.

After being introduced to the packed theater as the “embodiment of American independent film,” Linklater, who was wearing a custom-made cowboy shirt showing scenes from the movie Rio Bravo (yes, another movie I haven’t seen), made a very brief speech, describing Bernie, his sixteenth film, as “a labor of love.” Black and McConaughey took their turns at the microphone, praising Linklater for what he had done for their careers. Then MacLaine began to talk about the way Linklater had said nothing to her after each of her takes during the filming except “Well, hmm, I don’t know.” I held my breath, waiting to see what she would say. “But I have to admit,” she continued, “that Rick taught me the profundity of the words ‘I don’t know.’ By not telling any of us exactly how we should be, we had to find our characters for ourselves.”

I looked at Sledge, the producer, who looked back at me. We couldn’t believe it. Somehow, Linklater had won over his fiercest critic.

The lights went down, the movie began, and the crowd stared curiously at the opening scene: Black, as Bernie, fastidiously teaching a group of students at a mortuary school his secrets to preparing a body for a funeral. Soon, the scene shifted to Carthage, where Bernie began his new job at a funeral home, made friends with just about everyone in town, sang and danced, and first met Mrs. Nugent. When the gossips appeared, the audience roared. Kay Baby got one of the biggest laughs of the night when she discussed the possibility that Bernie was gay because he liked to wear open-toed sandals.

Then, fifty minutes into the movie, came Mrs. Nugent’s murder, and the whole tone of Bernie starkly shifted. I could see people in the theater glancing at one another, as if they didn’t know whether they were supposed to keep laughing, which, of course, was exactly what Linklater wanted: comedy and tragedy, all intertwined.

At the end of the film, the audience vigorously applauded, and then everyone rushed for the free food and drinks at the post-premiere party, held on the rooftop of a parking garage next to the theater. Linklater was in one corner, talking to other famous movie directors, like Steven Soderbergh. In another corner MacLaine was holding court, accepting praise from her fawning fans. I caught her eye and waited to see if she was still mad at me for slipping away back in Bastrop. She walked up, gave me a big, beautiful hug, and said, “Skip!” A couple of people were staring at me, no doubt wondering who the hell I was, standing there in my Nordstrom shirt. I nodded at them and said, “Shirley MacLaine, personal friend of mine.”

A few months after the premiere, Linklater invited the gossips, the extras, and a handful of other Carthage residents, including Danny Buck, to see the movie in Austin at a special screening he had arranged to benefit the victims of the Bastrop wildfires. The gossips watched the screen with their jaws open, and they laughed so hard at their own lines that they turned red in the face. Afterward, an impressed Danny Buck told me he ended up liking the movie that he was expecting to hate, and then he added, “I wish there was some way I could have watched it before I had to prosecute ol’ Bernie, because I would have damn sure used ol’ Matthew’s ‘Bring in the freezer’ line.”

In Carthage, plenty of people were still sore that the movie was being released. One resident even approached David Tompkins, the owner of Carthage Twin Cinema, and asked him not to show Bernie. He responded by running a poll on the theater’s Facebook page, asking people in Carthage if they were for or against his screening the movie. More than 250 people responded, all of them “for,” except Peggy Marsh, who posted, “Have y’all found a cell phone in y’all’s theater?” Tompkins decided to show the film.

There is one person in particular, however, who may never get to see the movie. Linklater had put in a request to prison officials about screening Bernie for Bernie himself, who’s now at a unit in New Boston, suffering from diabetes and still fifteen years away from a chance at parole. “It only seems fair,” Linklater said. “It’s his story, after all.” But in late March, he learned that the prison had turned him down.

Meanwhile, the director, who is now 51 years old, has finished writing other scripts and has new movies in development (though he’s not saying which one he’ll pursue first). The East Texans have returned to their normal lives, and Danny Buck plans to run for reelection. “I expect all this Hollywood hoopla to blow over very soon, and then it’ll be back to chasing criminals,” he told me.

But Kay Baby hopes the hoopla never ends. She’s paid $200 to a “professional scrapbook person in Tyler” to put together a book of all her mementos from the Bernie shoot. What’s more, she has typed up her résumé and joined the Screen Actors Guild, hoping to be cast in another movie. When I called her recently, she said, “Honey, the other night I sat with Gary on our double-wide La-Z-Boy as we watched the Oscars, and I started crying when that woman from The Help came up to get her supporting actress award. I said to Gary, ‘That could be me one day.’ ”

“And what did he say?” I asked.

“Oh, honey, Gary didn’t hear me. He was already sound asleep.”