This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Joe Hernandez’ New Year’s Eve party seemed headed straight for disaster. That afternoon Joe walked into the cavernous Farmer’s Market on the western edge of downtown San Antonio only to be informed that his request for a permit to sell beer inside the hall had been denied. The news made his chestnut cheeks turn an ashen gray. How could he throw a party and at the same time deny three thousand thirsty Chicano hedonists, his gente, their beer? It was bad enough for Joe to lose five thousand extra dollars from the beer concession, but there was something even worse. A social gaffe like this might ruin his reputation.

And Joe’s reputation during the 23 years he had been performing with his band as Little Joe and La Familia had spread not only all across Texas but as far west as California and as far north as Minnesota. Although he had made some forty albums, Joe had built his reputation on his live performances in the neon-and-smoke wonderland of bailes grandes, the big public dances that are the essence of Chicano social life throughout the Southwest. There are a few other performers on the Chicano circuit who can charge as much as $10 at the door and still attract 3000 dancers on any given night, but Joe’s dances are still regarded as something even more special, particularly in San Antonio, where the grandest of bailes grandes are billed as “superdances.”

As Joe walked from table to table uttering polite apologies to the people who were beginning to fill the Farmer’s Market, he explained to me, “These people here, la raza, they’re all beer drinkers. I feel like I let them down tonight. They’re my guests and I can’t serve them beer.” Joe didn’t mention just how resourceful his guests could be in a pinch; many had already gone out and lugged in their own cases of beer, now stacked high on half the hall’s hundred tables. These guests were not only the young couples dressed in the Italian-cut sports coats, sleek pants suits, and stacked heels that one might expect—the Chicano version of a Saturday Night Fever crowd—but also older couples, their children in tow, who had come to dance, celebrate the New Year, hear Little Joe, and, perhaps, keep an eye on their teenage sons and daughters. A Little Joe dance was a major social event, appealing to both the young and old, the respectable and the flashy, in a way that has no equivalent in Anglo culture in Texas or anywhere else.

Joe wanted to impress everyone there that night, but there were two guests he particularly wanted to please: one was a prominent Chicano politician, the other a successful Anglo record producer. Joe’s career was at a crossroads. He could continue indefinitely with his special popularity among Mexican Americans, or he could modify his image to appeal to the larger American market. The Chicano politician was there to bolster Joe’s ethnic conscience; the Anglo record producer to tempt his show-business ambitions. Later they would spar in the opening rounds of the struggle for Joe’s destiny. But for now, the show had to go on.

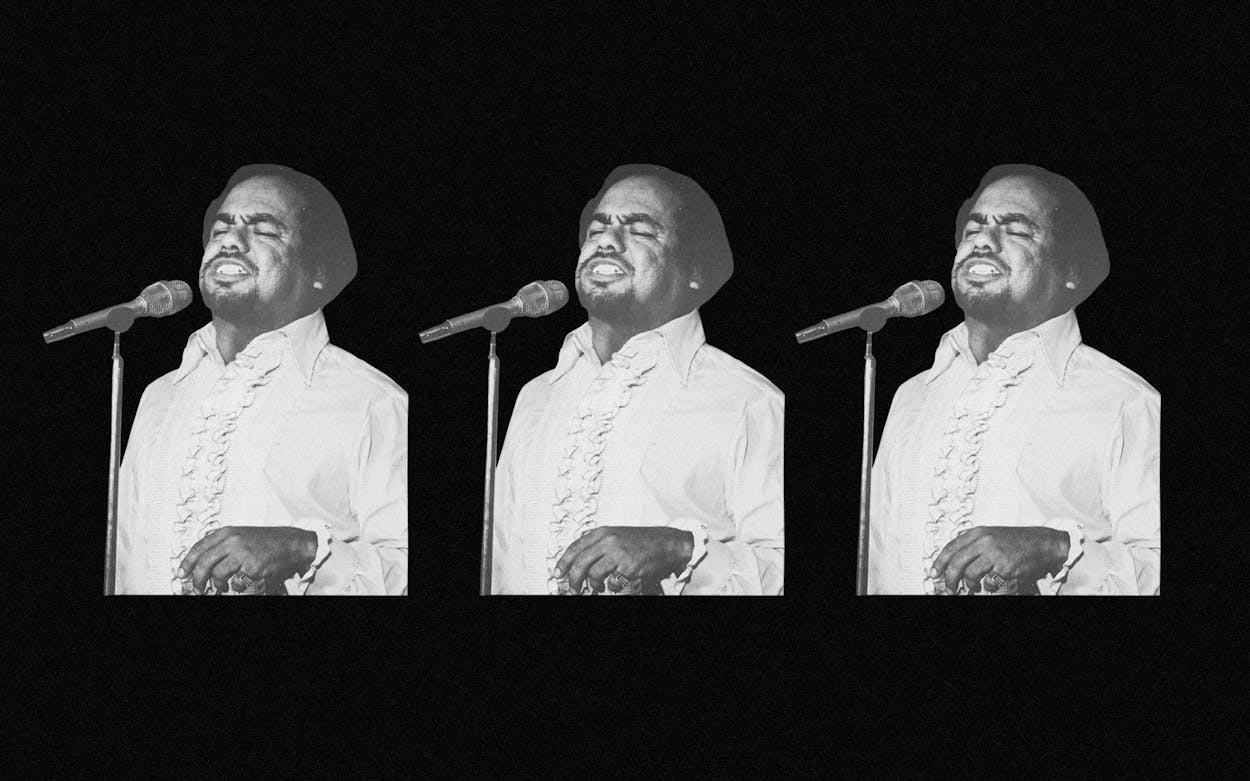

Joe’s set began with an abrupt blast of sassy brass followed by a spontaneous string of spine-tingling gritos, high-pitched emotive shouts that punctuate Tex-Mex music. No longer the humble, apologetic host, Joe howled louder than anyone else, baying a traditional “!Ajúa!” like a wounded coyote. With a self-assurance that magnified his diminutive five-and-a-half-foot stature, he tugged his shirt cuffs and grabbed the microphone, kicking off his usual opener, “Chaparrita de Oro” (“Little Goldie”), with the scream, “Where are you, my little brown mama?” With his brother Johnny in his ever-present Borsalino on one side and Bennie Muñoz on the other, Joe and his front line of vocalists were an impressively elegant sight in their matching blue crushed-velvet tuxes. But more awesome still were their perfect Spanish harmonies, held aloft by the six musicians of La Familia, immaculately clad in basic black tuxedoes. They played at full volume a sophisticated arrangement that completely obscured the fact that “Chaparrita” is nothing but a country polka.

“Don’t look at them, look out here on the floor,” advised a voice from behind me. It belonged to Judge José Angel Gutiérrez, founder of the Chicano La Raza Unida party, Zavala County political potentate, and rabid Little Joe fan. The real show, he pointed out, was on the once-empty concrete dance floor in the middle of the hall, which was filling up rapidly with spinning, twisting, bouncing couples who moved counterclockwise in a fluid promenade that looked like a vast human merry-go-round. The overwhelming majority were puro tejano, brown Texans, and the music belonged solely to them. The Judge let out a hearty laugh. “They’re coming out like popcorn now.”

The dancing would have been as lively if Sunny and the Sunliners, Jimmy Edward, People, The Latin Breed, The Mexican Revolution, or any of the other top-flight Chicano bands had been onstage instead. A full floor simply meant a satisfied clientele. (Applause, which suggests people are listening to and not participating in the music, is considered less than complimentary on the Chicano circuit.) What distinguished Joe Hernandez from other bands, and what attracted enthusiasts like the Judge, was Joe’s keen ability to transform his parties into cultural and political celebrations. La Familia might demonstrate their savvy musicianship with a rhythm ’n’ blues classic like “Knock on Wood” or an original disco number inspired by the group Chicago, but ultimately Joe always brought his audience back to their roots, no matter how Americanized they may have become. When Joe exhorted everyone to sing along with a song like “Cuando Salgo Los Campos,” a northern Mexican ballad about returning to the countryside, tears would frequently well up in the eyes of his listeners. Stressing la onda chicana, the Chicano thing, was the heart of Joe’s act, and it transformed him into a public figure larger than a mere entertainer.

By the second chorus of “Chaparrita,” Little Joe Hernandez had tossed away his jacket and rolled up his sleeves. A rush of fans surged toward the stage. Little Joe and Johnny, who has a cult following of his own, casually embraced the first women who reached them. They signed autographs during an instrumental break and posed with ardent fans for photographs.

When the first number ended, Joe charged right into one of his fiery raps while the rest of La Familia caught their breath. “Los gabachos [a pejorative term for Anglos] say that we’re not competitive, that we’d rather have kids than Cadillacs. If we cannot take command, if we cannot kick ass, then we’re not gonna be able to compete. You’re not black, you’ll never be white, so don’t waste your time. The brown team is your team. Let’s get our share of the cake.” The crowd around the stage moved in closer and occasionally a clenched fist shot into the air. Joe Hernandez sounded like a politician on the campaign trail, and, judging from the audience he held in sway, I remarked that he sounded like the best-known Chicano in the state.

“No, bato,” corrected Judge Gutiérrez. “He’s the best Chicano in Texas. He’s the king!”

Música chicana, known otherwise as música tejana, norteña, Tex-Mex, and the Brown Sound, is not really Mexican at all, though its origins are in that country and its lyrics are predominantly Spanish. Instead the music is wholly Texan and is considered foreign even in Monterrey. Its sphere of influence reaches as far as the Pacific Northwest, the Great Lakes region, and Florida, roughly the same circuit migrant farmworkers from the Southwest follow during harvest. The same language barrier that insulates Chicanos makes música chicana an acquired taste among our state’s English-speaking majority. Consequently, música chicana remains isolated, an anomaly in the backwater of the American pop mainstream, too often lumped together with Caribbean salsa, the Mexican mariachis, and other unrelated types of Latin music. Although bands like Little Joe’s can play in these styles and in others, such as blues, rock ’n’ roll, and bebop, the staple of their sound is the polka—highly syncopated, intricately arranged, but a polka nonetheless. That is the beat that gets people out of their chairs and onto the dance floor.

Unlike black music, which appealed to whites from its very beginning, música chicana has remained the property of the culture that created it. The music has managed to flourish simply because Chicanos are the largest untapped commercial market in the American music industry. Chicanos, not blacks, are the largest minority group in Texas and other Southwestern border states. There are more than twenty million Mexican American citizens in the United States and a large number of mojados (wetbacks) as well. These are the people who, week after week, come to the bailes grandes, who listen to the radio stations specializing in the Tex-Mex sound, and who buy records, all of them locally produced and locally distributed, by Little Joe and the other popular bands.

In spite of their large market in the Southwest, Chicano bands have always wished for wider acceptance. Since 1960, when two records by San Antonio bands—the Sunglows’ polka-rock instrumental “Peanuts” and Sunny and the Sunliners’ “Talk to Me”—made it to the Top Ten on national sales charts, other Chicano artists have been attempting to do the same thing. Two, Freddie Fender and Johnny Rodriguez, have been successful as middle-of-the-road country crooners, and the message of their success to other artists is quite direct: wider acceptance comes only by dropping Spanish lyrics (except, perhaps, for a chorus or two), performing songs with popular rather than Tex-Mex arrangements, and signing with a major record company and distributor. While most Tex-Mex artists would be only too happy to sign with a major record label, having watched Freddie Fender become famous, appear with Johnny Carson and Dinah Shore, and sell millions of records, they may not be as eager to drop the style of music they’ve played all their lives. That’s a real problem for Little Joe in particular, since he has made such a point of adding the rhetoric of brown consciousness and brown politics and brown solidarity to his act. At the same time, he has reached the pinnacle of his career in música chicana. To his thousands of local fans he is a star, a superstar in fact, though most güeros don’t know who he is. In an airport, restaurant, bank lobby, or bus stop, he is as anonymous as you or I.

He makes a good living, netting perhaps $50,000 per year, and his most popular records sell about 150,000 copies, in spite of their inefficient, local system of distribution. Yet, even with better distribution, Joe probably could not sell more than that without changing his sound to appeal to a broader audience. Nor is 150,000 enough records to interest a major company in signing a polka-crazy, bilingual band, when stars like Fleetwood Mac or Linda Ronstadt can sometimes sell that many in a day.

Still, counting all the gate receipts, record sales, beer concessions, recording studios, and so on, música chicana as a whole is about a $7-million-a-year industry in Texas alone, and that figure has not fallen on deaf ears. Judge Gutiérrez spent $6000 of the same federal grant Governor Briscoe claimed would make “a little Cuba” out of Crystal City to study the feasibility of establishing a cooperative, under his purview, that would promote, manage, and distribute La Raza’s music. On that New Year’s Eve he talked optimistically about his plans, all probably doomed, since the Judge has neither experience nor music industry connections. Still, Gutierrez represents brown consciousness to Little Joe and has enough influence with him that Joe has never said he wouldn’t sign with the Judge’s cooperative if the Judge ever got it going.

That same New Year’s, only a couple of tables away, sat a loose-jowled, casually dressed, middle-aged man named Huey P. Meaux of Houston, the legendary and notorious Crazy Cajun. A veteran record producer, manager, and one-man record company who has launched the careers of Freddie Fender, Doug Sahm, B. J. Thomas, and scores of others, Meaux had his own ideas about how to handle Little Joe and his music. He knew that the Chicano music business was in a state of eternal confusion. “They’d rather stab each other in the back than make money,” he told me. His solution, though, wasn’t federal aid or racial unity. He wanted to sign all the leading bands, including La Familia, under his aegis. Whatever Meaux may have lacked in brown consciousness, Joe had never said that he wouldn’t sign with Meaux either—if he got the right offer—since Meaux’s ideas were backed by all the right connections in the recording industry, and he had a proven track record of producing over forty million-selling discs. Capitalizing on Fender’s immense success, Meaux had recently started dabbling in música chicana after ignoring it for fifteen years. In 1977 he’d bought GCP and Bego, two of Texas’ major Spanish labels, and signed contracts with San Antonio’s Latin Breed and San Angelo’s Tortilla Factory, two bands with substantial statewide followings. Musicians in the clubs and dance halls were buzzing about the $10,000-to-$20,000, five-year contracts Meaux was dangling before any group with a name.

The New Year’s Eve dance was the first occasion the Judge personally met the Crazy Cajun. Though he regarded Meaux as an old-school gabacho who manipulates la onda chicana to his advantage, Gutiérrez good-naturedly offered to share some of his tequila, in light of the cerveza shortage. “But just a little bit,” he teased Meaux. “I’m not gonna give you the whole bottle.” Both men kept their eyes glued on the band while they engaged in some light verbal fencing. But after fifteen minutes of casual conversation, the Judge popped the inevitable question: “Who’s gonna get Joe first? You or me?”

Meaux, who’d been slightly unnerved by Gutiérrez calling him Harvey all night, suddenly found himself on firmer footing. He turned and stared at Gutiérrez, drawling in his thick, slow French accent, “Whoever he wants to go with, brudda.”

Little Joe knew Meaux’s power and influence, but he also knew his reputation for cutthroat dealings in financial matters, and Joe was not impressed with the amount of money Meaux was waving around. “Why should I sign up with him?” he had asked me earlier that night. “I can make that much money playing live in one weekend. Twenty thousand is cheap, man.” Nevertheless, Gutiérrez and Meaux were the two horns of Joe’s dilemma. Gutiérrez was clearly closer to Joe’s heart, the man who joined Joe on the stage to sing along with an old ranchera just minutes before midnight. But Joe was very careful not to slight Huey Meaux. He introduced “el gran productor de Freddie Fender” to the crowd four separate times.

The seventh son of fourteen children born to an immigrant couple from Aguascalientes, Joe was born in 1940 and raised in Temple in a two-room garage apartment. One room had only a tent roof and a dirt floor. As soon as he was old enough to work he joined the rest of the family traveling the farms of the Southwest, picking fruit, vegetables, and cotton for meager wages. He never had much formal education. Although his formative years were spent in poverty, Joe views them now with a touch of romanticism. “Six of us kids slept together in one bed and we dug it. My family was so tight because of the circumstances. I used to see my mother out there in the fields when she was pregnant, stooping down all day. But I didn’t consider that as hard times. We were all just doing what we had to do. My family isn’t as tight as we were, but I’m working on them. They’re a little more assimilated and adjusted to living in the material world. Each kid has his own room, his own bed.”

At fourteen, while the Hernandez clan was picking cotton in the sand pits near Altus, Oklahoma, Joe became the head of the family by necessity. His father, Santiago, had been arrested in Texas for possession of two marijuana cigarettes and sentenced to a 28-month stretch in Huntsville. “All of a sudden I was put in charge of everything—handling finances, collecting our wages, and driving the car without a license,” he proudly remembers. “Survival didn’t call for no rules. Nobody had time to ask what the rules were.”

Music also helped bind the family together. After work in the fields, Joe recalls, the family would gather under a tree and, after breaking out a bottle and some marijuana, would sing, simply for the pleasure. At the age of seventeen, Joe decided music had more to offer, and he spent his last day in the fields. “It was my birthday, a Friday, and I picked six hundred and eighty pounds of cotton that day. I wanted to set a record and I did.” His retirement was precipitated by his interest in making another kind of record. He’d begun singing and playing guitar with a friend’s band, David Coronado and the Latinaires, and had quickly decided to try to make his living in music. With styled hair, continental clothes, and shiny shoes, for a Chicano big band in the fifties, the Latinaires were spiffy men of the world. They played música alegre (traditional polkas), but also performed current Top 40 hits for their hip tejano following. They were the New Wave of their people’s music.

In 1959, David Coronado departed for a steady job in Walla Walla, Washington, and left the Latinaires to Little Joe. A dynamic vocalist and a mean blues guitarist, Joe had all the necessary ingredients to front the band. Two years later Joe’s brother Johnny joined, adding his sweet tenor to the harmonies and laying the groundwork for the three-man vocal setup of the present La Familia.

Money was scarce at first. Joe had to go into hock more than once so the Latinaires could afford new white shoes to match their uniforms. Still, under Joe’s leadership the Latinaires’ popularity steadily mounted. They had numerous Chicano hit records and, hoping for wider acceptance, they recorded every third or fourth album in English. Their main source of income, however, remained the stage shows, which had grown into James Brown–inspired revues complete with featured vocalists, dancers, and Las Vegas flash. Joe began to dream of building a musical empire. Following the example of other Chicano bands who split with their producers (who in most cases, except Joe’s, were Anglo), Joe broke his working agreement with Dallas’ Zarape Records in 1968, and formed his own record company, Buena Suerte. “Everyone was complaining about getting ripped off and never receiving royalties, so they all started their own record companies. I was just an artist, but I wanted to see if I could handle the record company on my own, too.” With the exception of Joe, Freddie Martínez (of Freddie Records), and Sunny Ozuna, most Chicano artists flopped miserably as businessmen. They had control of their careers, all right, but lacking a consolidated distribution system, sufficient operating capital, and experienced personnel, their product had no way of reaching the public.

Within a year Buena Suerte had seventeen bands and artists signed up, and Little Joe and the Latinaires were cresting near the top of the Chicano scene. But the social upheaval of the late sixties had a powerful effect on Joe. He started thinking about his heritage. The Latinaires suddenly sounded like a pseudo-sophisticated name for his band. He renamed it La Familia and stopped billing himself as Little Joe. He was now José María de León Hernandez. The band grew long hair and beards and their snappy show biz tuxes went into mothballs.

By 1972, the band made a clean break with the past. Joe moved to California in search of a new sound to replace the traditional ones he had grown up with. Under the tutelage of Luis Gasca, a superb jazz trumpeter and a Texas expatriate, La Familia was swept up in the Santana Latin rock movement. “Man, I had all these heavy musicians at my disposal. I was doing salsa because that was the big thing, but I did polkas, too, only with a fourteen-piece band. I was jazzing up everything.”

When Para La Gente, the first California album by La Familia, was released in 1972, Texas Chicanos thought they had been abandoned. The polkeros weren’t impressed by the influences of Gasca, Santana, and Mongo Santamaria. Sales dropped off and many stores in Texas quit handling Joe’s records. In 1975 José María de León Hernandez came back down from his heady experience and returned to Temple as Little Joe. Within the next two years the tuxes would be pulled back out of the closet and a happy medium established between musical experimentation and giving the hard core their polkas. And now, more than ever, chicanismo colored the stage routine.

Taking care of business is presently Joe’s main priority. “That’s what energizes me now,” he told me one night in his home in Temple. “That’s my ball when I get in there and it’s not up to anybody but me. It’s like rolling the dice. Every week I have to shoot craps for five thousand dollars and every week I have to win. Every week I have to keep the customers coming back.” But as his career has stabilized, his new role as statesman has evolved into almost a full-time endeavor. “Somebody needed to develop la cultura. We’re not the gifted ones or the appointed ones to do it, but I didn’t see anybody else really striving for it. It had to be done.”

We were sitting in the dining room of his sprawling ranch-style home. Thickly carpeted and softly lit, it looks like any upper-middle-class dining room except for the Mexican handcrafted furniture and the altar at one end of the room scattered with figurines, pictures of saints, a three-dimensional portrait of the Last Supper, and his brother Rocky’s photograph next to a burning candle at the foot of a crucifix. Sipping a scotch and water, Joe said, “I don’t feel like I’ve let down la cultura. No matter what kind of music I do, I’ll always show who I am. Commitment is the difference. This guy in California, Jim Castle, enlightened me about that. He’s the person who, with Luis Gasca, got us involved with fund-raising benefits for the United Farmworkers in the Bay Area. I asked him once why he did it and he explained commitment to me. Later, he went commercial, promoting concerts, so I told him it was beautiful he was committed in the past, but it went a little deeper with me. Myself, I can never get out of who I am. I can’t drop this thing tomorrow and go commercial. I’m brown for good. It’s a lifetime commitment.” He slammed his shot glass down on the table and pointed to the altar. “Look at that. I’m not trying to run away from my culture. No way I’m gonna do it.”

He then mentioned that Judge Gutiérrez had called him recently, and invited Joe to come to Mexico City. A group of Chicano dignitaries were to discuss immigration problems with President José López-Portillo, and Gutiérrez, partly in gratitude for Joe’s fund-raising efforts and his ability to hold an audience’s ear where politicians could not, wanted Joe along. “Why don’t you come, too?” Joe asked me. “The Judge and some others will be there. You can meet all my heroes.”

Four days later Joe Hernandez and I arrived in Mexico City. The purpose of the delegation’s visit with López-Portillo was to apply a wedge of pressure between the United States and Mexico regarding Jimmy Carter’s proposed immigration policy, to which the Chicano leaders were opposed for a variety of reasons. In the previous two months a procession of American officials, including Vice-President Walter Mondale and California Governor Jerry Brown, had paid courtesy calls to López-Portillo, purportedly to suggest, among other things, that the U.S. government might be more amenable to purchasing some of Mexico’s huge surplus of natural gas at their advertised price of $2.60 per thousand cubic feet (considerably higher than the current federally controlled ceiling for interstate gas) if López-Portillo would support Carter’s immigration plan.

Never before had Chicanos presented such a unified front. LULAC (the League of United Latin American Citizens), the GI Forum, La Raza Unida party, the land grant activist Alianza Federal de Pueblos Libres, IMAGE (Involvement of Mexican Americans in Gainful Endeavors), and MAPA (Mexican American Political Association) had sent representatives to speak against the Carter plan.

But where exactly did Joe, as the sole representative of la cultura, fit in? His political speeches from the bandstand may have been a legend back home on the party circuit, but in Mexico, surrounded by real politicos, they seemed out of place.

In the lobby of the Del Prado Hotel, beneath a powerful mural by Diego Rivera, Joe joined the Judge and the rest of the delegation on the night before the meeting with López-Portillo. The Judge reassured Joe, “Just say what you always do at your dances. It’s just another gig, only your audience is going to be the President.” But when Joe was introduced as the musical voice of Chicanos in Texas to Ed Morga, the head of LULAC from Los Angeles, Morga asked good-naturedly, “Can you get us Freddie Fender for a benefit?”

Morga, the Judge, Joe, the delegation’s Mexican hosts, and Frank Shaffer-Corona, a Gutiérrez protégé, whose position as a member of the Washington, D.C., school board earned him the distinction of being the only Chicano elected to civic office in the nation’s capital, retired to a Sanborn’s coffee shop (“but another example of American cultural imperialism,” announced the Judge) to map out the next day’s strategy. Everyone briefly stated what they wanted to emphasize to the President. Everyone but Joe. He remained quiet and listened. “This is my education,” he told me. The Judge now was the star, and Joe, at the very best, was a roadie who made sure the equipment was in proper working order and that everything ran smoothly. When the conversation broke up, Joe picked up the check.

The next day, riding with Shaffer-Corona to meet the President, Joe and I were caught in a crawling, bumper-to-bumper traffic jam on La Reforma. We arrived at Los Pinos, the President’s home, fifteen minutes after the scheduled half-hour meeting started, only to be refused admittance at the door. The meeting had already begun, an aide informed us. A few minutes later, however, we were ushered in, but the leaders were in intense discussion with the President, a balding, rather dashing gentleman with long, gray sideburns and the slightly forced, nervous patience of an overworked executive. Faced with his big chance, in the middle of international negotiations, the best Joe could muster was an obsequious request to shake the hand of El Presidente. With his request granted, Joe spent the rest of the conference merely listening, taking it all in. López-Portillo assured the group that he would not let the sale of gas affect his position on immigration and promised Gutiérrez that Chicanos would be included in any immigration talks involving the border area and the bracero program. He expressed mild surprise when informed that Chicanos, at present, constitute a larger minority than blacks in some areas of the United States. Then a house photographer materialized and scurried around the room recording the event before the President was shuffled off into another conference room.

“It wasn’t such a big deal,” Little Joe whispered to me in the foyer of Los Pinos afterwards. “I could have said something that would have gone on for half the meeting, and it would have been different from what everyone else said. But these guys I’ve come with mean a lot to me. They’re my teachers. This is my education.” He introduced himself as José María de León Hernandez to Reyes López Tijerina, the land-grant activisit, but Tijerina didn’t know who he was until Joe handed him a Joe and Johnny postcard. Tijerina broke into a wide smile and grabbed his compadre in warm abrazos like a long-lost brother. “Little Joe and the Latinaires!” he shouted. He grabbed his daughter, who was standing nearby. “Look, baby,” he said, “it’s Little Joe!”

After his brief flirtation with real politics, Joe and I flew back to his real homeland, Texas, the next day. “I don’t really understand politics all the time,” he told me. “The thing I do understand is la cultura and music.” That night José María de León Hernandez, who by now had reverted once again to Little Joe, arrived in Temple and went immediately to work in the studio he was building. Politics was well behind him now and for the time being, both Huey Meaux and Judge Gutiérrez would be kept waiting in the wings. Joe was putting the finishing touches on a Schlitz commercial.

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Antonio