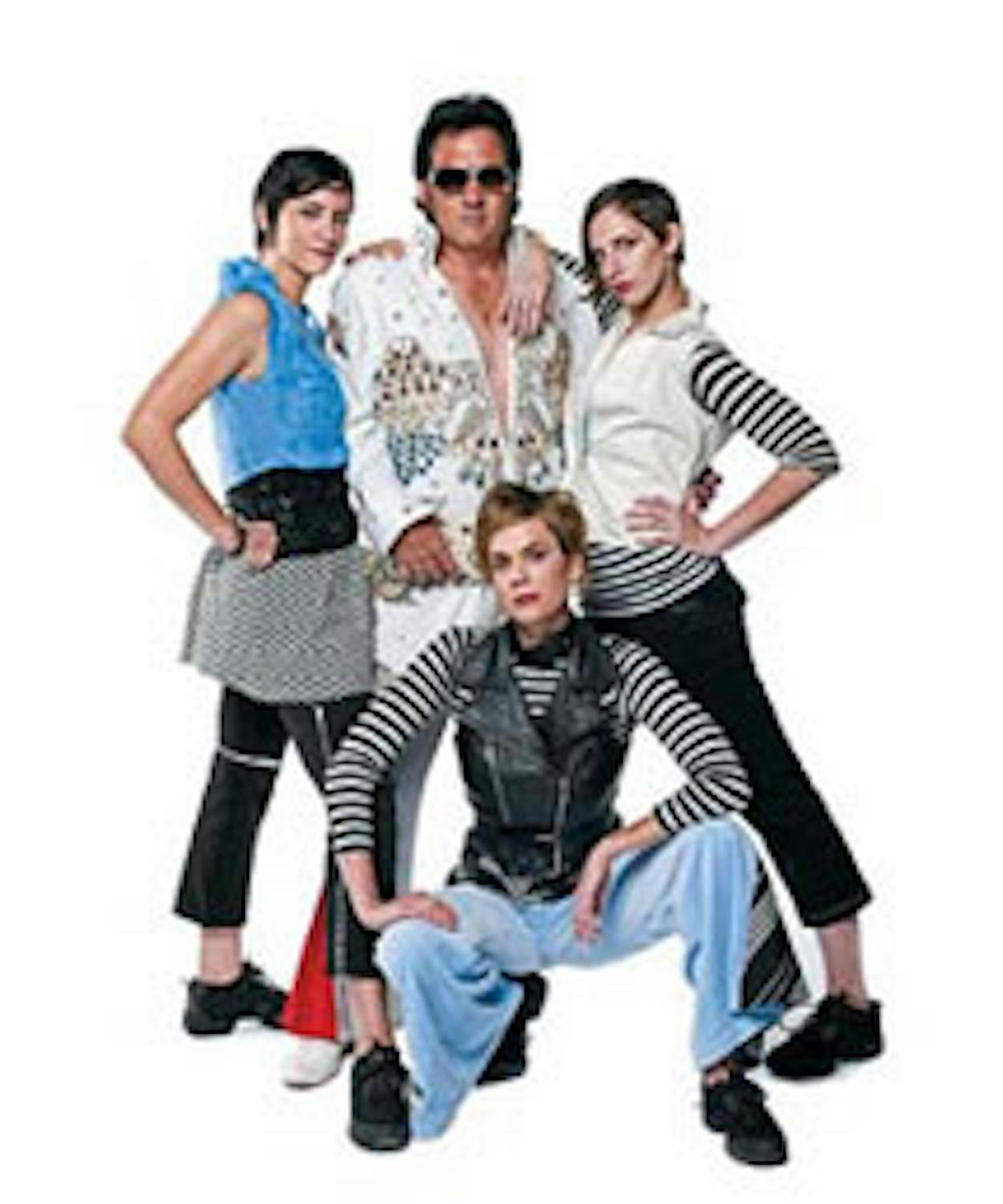

Austin, Los Fresnos It’s been thirty years since Elvis left the proverbial building, but demand for the King has never waned. (His estate still pulls in some $42 million a year, according to Forbes, which makes him the second-wealthiest dead celebrity, after Kurt Cobain.) The mania amps up yet again this month as fans across the world gather to commemorate his August 16, 1977, demise. But you don’t have to travel to Memphis to pay your respects. Elvis’s former Army buddy Simon Vega will be hosting the bi-annual Elvis Festival at his Los Fresnos home, which he’s turned into what he calls Little Graceland. Though it’s the smaller of the two parties Vega throws each year for his late friend (the other is in January to mark Elvis’s birthday), it’s no less of an event, with a handful of crooning impersonators jumbled in with the hundreds of out-of-towners who come to peruse the portraits and records and other Elvis memorabilia so lovingly displayed. You can, of course, travel to Vega’s shrine any time of the year—some fifty visitors stop in every week after calling to make sure the 72-year-old proprietor will be in—but this King Creole—themed bash is a good excuse to mix with fellow enthusiasts and mingle with those lucky enough to have once seen the pelvis-gyrating entertainer in person. Another observance of note will be taking place in the Capital City: Local ensemble Forklift Danceworks is reprising “The King & I,” one of its most popular performances. (If you’re thinking of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, you’re way off base.) After a trip to Graceland caught choreographer (and company founder) Allison Orr emotionally off guard, she took up the challenge of channeling Elvis’s larger-than-life persona through modern dance. “I really fell for him,” Orr says. The resulting hour-long piece features three dancers, Orr included, and up to five impersonators (Austinite Donnie Roberts, known as the Texas Elvis, is the lead tribute artist), and it manages to capture both the tragic and humorous facets of the legend’s legacy. Take, for instance, one montage in which Orr and her counterparts lovingly—and gracefully—assemble a fried peanut-butter-and-banana sandwich. (If your curiosity is overwhelming you, you can see excerpts of the show at youtube.com.) Plans are currently under way for a tour, which would take The King & I to the small-town municipal auditoriums—from Big Spring and Sweetwater to San Angelo and Greenville—where Elvis once played. Even now, thirty years after his last concert, we’re all still enthralled with the man who became the King of rock and roll. Elvis Festival: Aug 18. 701 W. Ocean Blvd, Los Fresnos; 956-233-5482. The King & I: Aug 2—18. Arts On Real, 2826 Real, Austin; 512-472-2787; forkliftdanceworks.org

All That Jazz

Houston A scat cat can find any number of beboppin’ events around Texas, but this month the hot spot is in the Bayou City. The Houston International Jazz Festival has been around since 1991, it’s just the right size (not too big, not too small), and it ultimately serves a greater purpose: Proceeds go to founder Bubbha Thomas’s educational programs, including the Summer Jazz Workshop, an intensive month-long band camp that schools local youth in all things jazz. The pupils’ payoff comes during the festival, when they get to perform alongside musical greats. And though this year’s lineup may not seem as worldly as it has in the past (only a few of the headliners hail from outside the U.S.), there will be plenty of multicultural intermingling. The main event—Saturday’s Jazzmasters Tribute—features keyboardist and pianist Gregg Karukas, lyrical guitarist Chris Stranding, urban funk saxophonist Paul Weimar (better known to fans as Shilts), versatile Latin guitarist Norma Zenteno, and Bubbha Thomas himself (his reputation as a drummer precedes him). Throw in a contemporary four-piece Australian jazz band (Void, the opening-night act) and a Sunday bill stacked with soulful vocalists (Eric Roberson, Terisa Griffin, and Anthony David) and it adds up to an enticing alternative to yard work and weekend errands. Besides, you’ll be doing it for the kids. Aug 3—5. Jones Plaza, Louisiana & Capitol; 713-839-7000; jazzeducation.org

Gone With the Wind

Big Spring Skydivers seem downright levelheaded when compared with hang gliders: It’s one thing to free-fall for a few minutes and score a quick high; it’s quite another to stay aloft thousands of feet in the air for hours at a time as you zoom along for miles. It makes sense, then, that the sport’s best (and seemingly mad) professionals are making their way to West Texas this month for the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale World Hang Gliding Championships. What better place than the Lone Star State to prove you’ve got cojones? Sanctioned by the FAI (that’s the global governing body for air sports), the event boasts a stunning roster of top-ranked gliders from about thirty countries. Now, you might be wondering why Big Spring, of all places, has landed such a high-caliber competition. One word: “thermals.” And no, we’re not talking cozy pajamas. They’re the columns of warm rising air that provide the all-important lift that allows birds to soar and gliders to, well, glide. There aren’t many places where the wind whips and gusts as it does over the flat expanses of West Texas, and the six-pilot teams are counting on the natural abundance to lift them to victory (pun shamelessly intended). Interestingly, Big Spring beat out Podbrezova, Slovakia, by a 14—13 vote to earn this year’s hosting honors. Because there’s nary a hill or a mountain of any real consequence in these parts, the gliders will have to be taken up about two thousand feet by ultralight airplanes for each day’s start. For spectators, who can stretch out on bleachers at the local airport, the hour-long mass launch is by far the highlight. What goes up must come down, of course, but not all the pilots will make it back to where they began, although it’s worth waiting around for four to six hours to try to see some landings. Before takeoff, the teams are given detailed goals to accomplish: Fly to Lubbock and back, for example, or coast over specific spots on a triangular route. (They also have their own objectives: Don’t end up too far south, lest you have to land in thickets of mesquite and cactus; don’t drift over the local prison.) Every evening, the gliders will turn their GPS tracking devices in and the officials will tally the results; by the end of the nearly two-week contest, awards will be given out to the pilots who’ve flown the farthest, stayed in the air the longest, and have reached the highest altitude. In this competition, though, skill will take you only so far. The caprices of the wind will do the rest. Aug 7—19. McMahon-Wrinkle Airport, 3200 Rickabaugh Dr W.; 432-264-2362 or 800-616-6888; ozreport.com/2007worlds.php

Best in Show

Fort Worth It’s hard to imagine that many—if any—of today’s cinematic offerings will be held up as artistically significant masterpieces in fifty years’ time. (Though there’s something to be said for mindlessly entertaining blockbusters, who wants Ocean’s 13 and Transformers to be remembered as shining examples of this decade’s best movies?) The Magnolia at the Modern film series happens to be offering the perfect antidote to summer’s trilogy binge with Essential Arthouse: 50 Years of Janus Films, a ten-day presentation of fourteen foreign classics. Plucked from the much-lauded archives of Janus Films, one of the leading theatrical distributors of the fifties and sixties, these selections are reminders that good art—in any medium—stays relevant even as the decades pass. Two not to be missed: Swedish director Ingmar Bergman’s Smiles of a Summer Night, which will charm even the most jaded cinephiles with its comedic plotline (an unconsummated marriage, an illegitimate child, lots of lovers); and Children of Paradise, the epic French romance that has a lovesick mime as its hero. At $7.50 a pop (and only $5.50 for museum members), each viewing costs the same, if not less, than whatever’s playing at the nearby multiplex. Plus, a local critic or industry insider will offer his thoughts on the work before most of the screenings. (TEXAS MONTHLY writer-at-large Christopher Kelly, who is the film critic for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, will be introducing the 1959 tragicomedy The Rules of the Game.) Aug 9—19. Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, 3200 Darnell; 866-824-5566; themodern.org

Out There

Houston The Contemporary Arts Museum Houston can be forgiven if its latest exhibit seems less than precisely defined. “Nexus Texas,” opening this month, is (very) broadly described as “new work by a group of artists living and working in the state.” That’s quite a pool to choose from, but the CAMH’s three organizing curators have managed to select sixteen creatives from all parts and all backgrounds who work in just about every medium you can think of. The one thing they have in common, though, is that none are household names; most are familiar only to those who troll obscure galleries and read online art zines. Luckily for both artist and viewer, a lack of widespread recognition does not coincide with a lack of talent, at least not here. Take for instance Jeff Zilm’s eerily arresting paintings, which are made with pigments stripped from 35mm movie film negatives that are then trickled onto canvas. The result is light wisps of images on a nearly blacked-out surface that conjure up the amorphous faces of ghosts. Equally as conceptual, though a 180-degree turn in the other direction, are Sterling Allen’s quirky offerings, such as his found-object creations. Chicken Wheel, for one, is just as comic as it sounds: two yellow plush-toy chicks suspended from green garden hoses that are attached to a children’s bicycle wheel. You can’t miss it on his Web site, sterlingallen.com. Amy Blakemore’s poignantly simple photographs, on the other hand, are easy to miss if you’re not right in front of them. Included in the 2006 Whitney Biennial, her soft-focus snapshots—often portraits of friends (think old ladies with beehives) and familiar suburban landscapes (a deer decoy in the backyard)—show off an acute eye. It’s important to keep in mind that “Nexus” is not meant as a survey or celebration of the state’s best or even next best. There’s something refreshing about what it is meant to be: an openly subjective reminder that artistic currents are running deep in Texas, if we only know where to look. Aug 18—Oct 21. 5216 Montrose Blvd, 713-284-8250, camh.org

Symphonic Salute

Fort Worth Among a symphony orchestra’s responsibilities, one is foremost: its artistic—even moral—obligation to stay true to a composer’s intentions. It is this commitment to capture even the most nuanced aspects of a work that ultimately maintains the music’s integrity over centuries. The Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra takes on a rather challenging oeuvre this month as it uses its annual Great Performances Festival to kick off a three-year cycle of works by Gustav Mahler, one of the twentieth century’s most noted post-romantic composers. During his lifetime, though, Mahler was known not for his compositions but for his skill as an operatic and orchestral conductor. At the age of 37 he became the director of the Vienna Opera, a position that required him to convert from Judaism to Catholicism before he was allowed to take the job. After ten years there, and after a good run of bad luck (the death of his eldest daughter, the discovery that he had a disabling heart condition, and continued anti-Semitic blows in the press), Mahler and his family moved to the U.S., where he lasted only one season at the Metropolitan Opera before being replaced. The following year, he signed another big contract, this time with the New York Philharmonic; in 1911 he fell ill, conducting his last concert in a fever (against doctor’s orders) before dying a few months later at the age of 50. It wasn’t until the sixties that Mahler, the formidable symphonist, was embraced as a revolutionary composer. The same characteristics of his work that had so inflamed critics when he was alive—the thunderous emotion, the expressive harmonies—now seem prescient. But his symphonies, monumental in emotional scope and grandiose in length, still remain delightfully convoluted. Along with several of Mahler’s vocal works, the FWSO is first tackling Symphonies no. 1, 5, and 9, but it’s the ninth that underscores the tragedy that so often coincides with genius. Mahler was deeply concerned about what has come to be known as the “curse of the ninth”; several of his predecessors, namely Ludwig van Beethoven and Anton Bruckner, died after completing their ninth symphonies. Mahler’s ninth is considered to be his most intense and is held up as one of his masterpieces. It was also, just as he’d feared, the last symphony he would complete. Aug 23—26. Bass Performance Hall, 4th & Calhoun; 817-665-6000; fortworthsymphony.com