Without exception, each man who saw the lifeless body of Betty Gore the night of June 13, 1980, reflexively averted his eyes. Even those who already knew what lay beyond the utility room door were never bold enough to look more than a moment before closing the door. Few looked at the head at all—the sight was too horrible—so the early reports as to the manner of death were conflicting, and usually wrong.

It was a small room, no more than twelve feet long by six feet wide, made smaller by the presence of a washer, a dryer, a freezer, and a small cabinet where Betty had kept toys and knickknacks. In one corner were a brand-new toy wagon and a child’s training toilet. Closer to the center of the room, where the freezer stood against one wall, were two dog-food dishes and a bruised book of Mother Goose nursery rhymes. The book had a white cover, which stood out in sharp relief because, in the harsh overhead light that glared off the harvest-gold linoleum, it was one of the few objects in the room not coated in blood.

Her left arm was the first thing they noticed after opening the door. It lay in a pool of blood and fluid so thick that the arm appeared to be floating above the linoleum. To get a look at her face, the men had to walk around the ocean of red and black to get closer. What they saw was even more unsettling. Her lips were parted, showing her front teeth, the mouth fashioned into a half-grin. Her hair radiated in all directions, a tangled, soaked mass of glistening black. And Betty’s left eye was wide open, staring down at the gaping black craters in her arm. As to her right eye—she appeared to not have one. The entire right half of her face seemed to be gone.

A few feet from Betty’s head and half concealed under the freezer was a heavy, wooden-handled, three-foot-long ax. The police who investigated Betty Gore’s death at first could not believe that anyone as small as Candy Montgomery had the physical strength to wield that ax so brutally. Even as their suspicions about her grew, they found it hard to believe that this pretty, vivacious, utterly normal suburban housewife could make such a vicious attack. She was a loving mother, a devoted wife, a churchgoer, and everyone’s friend. And she wasn’t putting on a cynical act. She really was as normal and likable and good as she appeared—except for one dark corner of her soul that even she did not know about.

Thank God for the Country

It was a church service that first brought Candy Montgomery and Betty Gore together, and it was the church that led them to their times of closeness and, eventually, to their mutual hatred and Betty’s brutal death. The Methodist Church of Lucas was, more than most places of worship, an institution controlled by women. The center of Candy Montgomery’s universe, almost from the day in 1977 when she moved to her dream house in the country, was the drafty white clapboard building known to its congregants simply as the church. Set back from the roadside, paint peeling, steeple rusted, its floors echoing hollowly under the tread of men’s heavy soles, it did not at first resemble a place likely to house the more liberal strains of Methodist theology. The church buildings sat on a slight rise surrounded by fallow blackland wheat fields on three sides and a farm-to-market road on the fourth. When the sky was clear and the wind strong, as it was, the landscape had the feel of a rough and untamed outpost, solitary and a little forbidding, not beautiful but stunning in its brown and gray emptiness.

The country, as the people who settled there liked to call it, was eight to ten amorphous little towns in eastern Collin County, but it really had no name. Most of its residents had come there to escape something: cities, density, routine, fear of crime, overpriced housing, the urban problems their parents had never known. They came in the seventies, just about the time the Dallas developers started buying out the farmers one by one, and they settled on pasture-size lots in homes designed exclusively for them by architects happy to get rich by satisfying their personal whims. They sent their children to a little red schoolhouse, joined a civic club or ran for the town council, and started going to church again when they found the quaint little chapel by the roadside of Lucas. Twenty miles to the southwest were the teeming freeways of Dallas, the huge electronics corporations where many of them worked as engineers and physicists and computer analysts, the endless chain of suburban housing developments and shopping malls and office centers running due north out of the city. But here there was quiet and solitude and control over their lives. Some of them spoke of it proudly. “This is the way things were back home,” they would say, or “Thank God we had enough money to move to the country so kids could get a good education.” The country was pure, untroubled, safe, innocent, a vision of regenerate America.

Slicing through the heart of the country was FM Road 1378, a tortuous two-lane blacktop connecting McKinney, the county seat, with Wylie, an old railroad town now given over to tract homes and light industry. Both towns were older and more authentically Western than anything in the twenty miles or so between them, for 1378 had become the main artery for the new subdivisions full of fantasy architecture: houses shaped like Alpine villas, houses dolled up like medieval castles, houses as forbidding as national park pavilions or as secluded as missile bases, hidden in thickets along the shores of Lake Lavon. Juxtaposed to those personal statements were the more familiar examples of prairie architecture: trailer homes, bait shops, window-less lodge halls, an outdoor revival shelter, ghost-town cemeteries. The only connection between past and present was the ubiquitous white horse fences that proliferated along the highway and around many of the brand-new houses, in inverse proportion to the number of horses needing corrals.

“Would You Be Interested in Having an Affair?”

Candy Montgomery would always be able to remember the precise moment when she decided she would go to bed with Betty’s husband, Allan Gore. It happened on the church volleyball court, on a late-summer day in 1978. Candy and Allan both tried to make a play on the same ball—and collided. It was a harmless bump, really, and went unnoticed by everyone else on the court, but for Candy it brought a revelation: Allan Gore smelled sexy. For several weeks she had been talking abstractly to friends about having an affair. Candy wanted something to shake up her “very boring” life with Pat. She was explicit about the kind of affair she was interested in: transcendent sex. As she put it, “I want fireworks.”

Then she bumped into Allan Gore and wondered to herself, “Could a man like that make the earth move?” At first glance he didn’t look like it. Allan had a receding hairline and the beginnings of a paunchy midsection, and he dressed blandly, to say the least. But in other ways he was the kind of man she might be able to have a good time with. She had known Allan for only nine months, but it seemed much longer. He was a lot like her: active in the church, a lover of kids, the outgoing, personable half of a mismatched couple. Allan sang in the choir, helped organize the sports teams, he did all the things that Betty never seemed to want to get involved in. He had a sense of humor. It was only natural that he and Candy would see a lot of each other. More to the point, a tiny, insistent voice in the back of Candy’s brain kept telling her that Allan Gore was as anxious to go to bed with her as she was with him.

It had begun with little things. Allan seemed to joke with her more than he joked with the other women at church. He teased her about her volleyball skills, and every once in a while he’d give her a sly wink, as though they shared some little secret. After choir practice the two of them would occasionally chat a little longer than necessary or loiter in the parking lot while the others were getting into their cars. The flirting was subtle. Sometimes it was so much like Allan’s natural friendliness with everyone that Candy doubted it was a real flirtation. But then Allan would do something that was unmistakably designed to get her attention, and she would start wondering all over again. As the weeks went by, she started fantasizing about sex with the man who smelled so nice. Candy was almost 29 years old and sexually frustrated. She was totally honest with herself about that. How many more years did she have to find out what she was missing? Not many. She decided to do something about it.

She got her chance one night after choir practice. Allan was already getting into his car when Candy spotted him. She strode up to the passenger side and opened the door. “Allan,” she said, leaning into the car, “I want to talk to you sometime, about something that has been bothering me.”

“Oh?” he said. “How about right now?” Candy slid into the seat beside him. She didn’t even look at him.

“I’ve been thinking about you a lot and it’s really bothering me and I don’t know whether I want you to do anything about it or not.” Allan, a little confused, said nothing. “I’m very attracted to you and I’m tired of thinking about it and so I wanted to tell you.” And with that, she jumped out of the car, slammed the door, and hurried across the parking lot.

Allan felt shocked and flattered and a little ridiculous. He wasn’t shocked by Candy’s directness—he had known her long enough to realize that she spoke exactly what was on her mind—but he was nonplussed that another woman was interested in him sexually. He was also surprised, and secretly pleased, that it was Candy. Even though she wasn’t what you would call a classic beauty, she was one of the most attractive women in the church, in his opinion, and she was certainly the most fun to be with. Then a wave of doubt overtook him: maybe Candy was just flirting, in her own way, because all she had really said was that she had been thinking about him. But such an odd way to say it.

Allan thought about Candy a lot over the next few days, and he wondered whether she would say anything else the next time they were together. He thought about calling her but then felt silly and awkward. He also thought, a little guiltily, of how different Candy was from his wife. Betty was as dour as ever; Candy was always up, always busy, self-confident, easygoing, warm.

Betty Pomeroy had been one of those girls whose conventionality made her the frequent center of attention. She was pretty; she had an innocence about her and a wide Hollywood smile that had made her one of the most popular girls in her tiny hometown of Norwich, Kansas. In college Betty fell in love with her math teacher, and when she and Allan Gore decided to get married, her family and friends were surprised. They couldn’t see what she saw in him. Allan was a small, plain man with horn-rim glasses and puffy cheeks and, even at a young age, signs of a receding hairline. He was also shy, which often made him come across as stern or aloof or even snobbish.

Betty and Allan were married in January 1970 and they eventually settled in the suburbs of Dallas. When their first child was born, Allan was working for Rockwell International, an electronics conglomerate and major defense contractor. In 1976 Betty took a job teaching at an elementary school in the small town of Wylie, about ten miles east of Plano, but she didn’t enjoy her work for very long. She couldn’t control her unruly students, and at the same time she couldn’t bear to be left alone at home when Allan had to travel.

In spite of her unhappiness, though, Betty had decided, as a new school year began in the fall of 1978, that they should go ahead and have their next child, but this time she wanted the pregnancy planned down to the exact week so that the baby would be born in midsummer and she wouldn’t have to take any time off from teaching. This was especially difficult, since the Gores’ sex life had dwindled to almost nothing, and when they did have sex, it was completely mechanical. Now Allan was required to have clinical sex with Betty every night during her estimated fertility period, in the name of family planning. He felt a little resentful; he had the distinct feeling that he was being used. That, combined with Betty’s usual complaints about minor illnesses, made Allan’s marital future look bleak indeed when compared with the bright, happy-go-lucky face of Candy Montgomery, full of promise and, he had to admit, allure. That didn’t mean he didn’t love Betty or that he would ever do anything to hurt her. It just pleased Allan that a woman like Candy would feel those emotions for a man like him.

A week or so after the choir practice, Allan saw Candy again. It was after another church volleyball game. Allan and Candy stayed to clean up the gymnasium, and afterward they walked out to the parking lot together. When they reached her car, Allan said, “Now what was it you had in mind?”

“Get in,” said Candy.

Allan slid into the passenger seat.

“Would you be interested in having an affair?” she asked.

Despite all his mental preparation, Allan wasn’t prepared for something that direct. “I don’t know what to say,” he said.

“It’s just something I’ve been thinking about and I wanted to say it so I don’t have to think about it anymore.”

“I don’t think I could, Candy. I don’t think it would be a wise thing to do, because I love Betty. Once when we were living in New Mexico she had an affair that hurt me a lot, and I wouldn’t want to do that to her.”

Candy was surprised to realize how much Allan had thought about his answer. “That’s fine, Allan. I love Pat, too. I wouldn’t want to hurt him, either.”

“Betty just got pregnant again, too, and it would be unfair to her, especially since I don’t feel the same way about you that I do about her. So I probably couldn’t do something like that.”

“Okay, Allan, I was just putting the option out there because of how I felt and it’s up to you to decide. I don’t want to hurt your marriage. All I wanted to do was go to bed. I won’t mention it again.”

Allan leaned across the seat and softly kissed Candy’s lips. Then he quickly got out of the car.

The Last of the Red Hot Lovers

One thing Allan Gore always believed in was that marriages are forever. That’s why, when his sexual relations with Betty started to become routine and unimaginative, he cast about for explanations. He enjoyed sex, and he knew that Betty did, too, and there was nothing wrong with them when they were happy and untroubled together. But lately there was not much enthusiasm in the bedroom. Allan was working hard, even though he didn’t travel any longer because Betty had a deep-seated fear of being alone. She frequently came home from school full of tension, and she would sometimes use most of the evening grading papers for the next day’s classes. When you don’t spend a lot of time together in the evening, Allan thought, there’s usually not much interest in spending a lot of time in bed, either. Allan was afraid they were in danger of falling victim to complete boredom.

One solution Allan considered briefly was a program called Marriage Encounter. Some friends of his from church, JoAnn and Richard Garlington, had gone to a Dallas motel one weekend for a special Marriage Encounter session in which several couples talked about their marriages and tried to strengthen their commitment. Allan didn’t understand exactly what went on, but he knew that the Garlingtons came back beaming and almost absurdly joyous. They said they were hooked on Marriage Encounter and immediately set about trying to get other couples to join. If it had been anyone else but Richard and JoAnn, Allan would have mistrusted it, especially since Richard wouldn’t tell him exactly what happened during the Marriage Encounter weekend. “You won’t understand it unless you go experience it for yourself,” Richard said. Allan had to admit that the Garlingtons had seemed to be happier in the months since they were “encountered,” as they put it. One thing the Gores did need was something positive and revitalizing in their marriage, so one evening Allan tentatively suggested to Betty that they give Marriage Encounter a try.

“Why do we need something like that?” she said. “I have so much to do already. You don’t think there’s something wrong with us, do you?”

He could tell she would be upset if he said yes, and so he dropped the subject.

When Pat Montgomery married Candy Wheeler in the early seventies, he was one of the brightest young electrical engineers at Texas Instruments. Candy had been working as a secretary; she was petite and blond and a little impish, with a thin, pointed nose and a contagious high-pitched laugh. She was an Army brat, the daughter of a radar technician who had spent the twenty years after World War II bouncing with his family from base to base. Candy seemed born to the wandering life, though, blessed with an easy rapport with strangers and a coquettish exuberance that taught her at an early age what power women could exert over men.

Candy and Pat moved to the country in 1977 with a son and a daughter; by then, their marriage had settled into a routine. Pat was providing everything Candy had ever expected from him, including a $70,000 income from his work on sophisticated military radar systems at Texas Instruments. Candy did not mind taking care of the children and their house, but she was “bored crazy.” That was why, on her twenty-ninth birthday, the highlight of her day was a phone call that came completely out of the blue.

“Hi, this is Allan. I have to go to McKinney tomorrow to get some tires checked on the new truck I bought up there. I wondered if you’d like to have lunch, you know, to talk a little more about what we talked about before.”

It had been two or three weeks since the last time they had talked, in the parking lot outside the gym. Those weeks hadn’t been easy for Candy. She felt foolish after throwing herself at him and then being so calmly rejected. Besides being embarrassed, she was afraid that Allan would think less of her. She wanted to put the whole incident out of her mind, and the only reason she couldn’t was the kiss. If Allan were so dead set against the idea, why had he given her that enigmatic kiss on the lips just before he left? It was not what she would call a passionate kiss, but it was not a brotherly kiss either. And it didn’t help Candy’s peace of mind that she and Pat had been arguing more than usual lately. She had brought home some A+ papers from the writing class she was enrolled in, but all Pat would do was glance at them and pretend to understand. His insensitivity infuriated her and led to harsh words. To Pat they were arguments over nothing, but to her they represented everything wrong with their marriage.

Allan and Candy met at an auto repair shop in McKinney, the venerable county seat a few miles north of Candy’s house. Allan broke the ice right away by surprising her with a birthday card. On the front, it read, “For the Last of the Red Hot Lovers.” She opened it to find a small plastic bag of Red Hots inside. It was the kind of hokey gag card that Candy loved, and she was instantly touched. They got into her car and drove to a quaint little teahouse, where they talked about everything except themselves for the better part of an hour. Allan talked about Betty. Candy talked about Pat. They compared notes on their children, chatted about church matters. Candy got Allan to talk about his work for a while, and he in turn seemed interested when she discussed her creative writing course. Then, after the meal was cleared away and they began to sip their coffee, Allan said, “I’ve never done anything like an affair before.”

“I haven’t either,” said Candy.

“I would never be able to forgive myself if Betty ever found out about something like that. I think it would just be devastating to her.”

“I feel the same way. I wouldn’t want to see anyone hurt by this, Pat or Betty. We would have to be so careful that no one would ever know except us.”

“I’ve been thinking a lot about what you said, about not wanting to get emotionally involved. That would be very important for me.”

“Me, too, Allan. I just want to enjoy myself without hurting myself or anyone else.”

“Well, let’s think about it some more, and maybe we should think about the hazards some more and whether we want to take that risk.”

“Fine. I think we should.”

Little else was said that day, but within a week Allan called Candy again while Pat was at work. They chatted more about the risks of having an affair, their fears of doing something that would ruin their marriages, but they also talked about their mutual attraction and were obviously excited by the prospect of a tryst.

“You know, if you don’t go to bed with me pretty soon, Allan, then you’ll never be able to live up to the expectation I have of you in bed,” Candy said, giggling.

“I know,” he said, not laughing. “I’ve thought of that.”

The next month consisted of strategy sessions for what must have been the most meticulously planned love affair in the history of romance. It began with tentative phone calls from Allan, asking about this or that. “When would we do it?” “What if somebody saw us?” Soon after the lunch at the teahouse in McKinney, they arranged to meet for lunch again, this time at the parking lot of Allan’s office in Richardson, from which they drove to a nearby restaurant. Allan was accustomed to making his own hours at work, so a long lunch break was no problem, but they could save time if Candy picked him up. From talking about the hazards of the affair, they moved quickly to a consideration of ways they could possibly avoid those hazards. They talked a great deal about emotional involvement. They agreed that there would be none of that; it was too dangerous. As long as they limited the affair to sex, they were safe.

Allan started looking forward to his daily call to Candy from work. Candy, just as starved for affection, looked forward to it as well. Allan was growing much more comfortable with the idea of an affair, mainly because he discovered, to his surprise, that he could go to lunch with Candy, talk with her intimately on the phone, and then go home to Betty and always be completely normal. Candy always felt completely normal around Pat, perhaps because she was confident he would never suspect a thing. Still, Allan and Candy hesitated to take the plunge.

At the end of November Candy came up with the best stratagem of all: she invited Allan to her house for lunch. She fixed her famous lasagna for the occasion. She also decided, before Allan arrived, that if nothing happened soon, she wouldn’t spend any more time on this. She had done what she could to make it happen. It was really Allan’s decision to make. He was so damned indecisive that she was starting to think he wasn’t aggressive enough to do this anyway.

As soon as Allan walked into the Montgomery house that day, he broke into laughter, for the first thing he saw, hanging above the room, was a huge piece of butcher paper. On it, in Magic Marker, Candy had made two columns. The column on the left was headed “WHYS.” The column on the right said, “WHY-NOTS.” When she said she was inviting him over to discuss the pros and cons, she wasn’t kidding. She also knew, from their last few phone conversations, that Allan was leaning toward a decision not to have an affair. The cute little sign eased the tension.

After eating, they sat in the living room and went over the list an item at a time. They took the why-nots first, beginning with the most important one: fear of getting caught.

“But that really shouldn’t be a problem,” said Candy, “if we’re careful.”

Allan was much more concerned about one of the why-nots farther down the list: the possibility that they would become emotionally involved. “We need to think about what we’re getting into,” said Allan.

“Allan, as far as I’m concerned, this is just for fun. I’m not serious about it. It’s just a companionship thing, and we shouldn’t be afraid of it. Whatever happens, we’ll do it for a while and then it will be over.”

“I’m afraid that I might get emotionally involved.”

“We just won’t let that happen.”

The whys on the list were a good deal easier: a sense of adventure, a need for companionship. Candy hadn’t gone so far as to put sex on the list, but they discussed that one, too.

“We’ll always wonder if we don’t do it,” she said.

“I know,” said Allan.

“It’s up to you, Allan. I know I can do it. I know I can act in an adult fashion and not take unnecessary risks. I’ve made up my mind, so just tell me if you want to do it.”

They didn’t make the final decision that day, but after Allan left, Candy thought to herself, “How much farther can you go?” They had already made too big a deal of something that should have been more natural. It wasn’t as though Allan Gore was her fantasy man or anything.

A few days later Allan called again.

“I’ve decided I want to go ahead with it,” he said.

Still, it didn’t happen right away. There were ground rules to be established, logistical problems to be worked out. This affair was to be conducted properly. Candy even made a list of rules one day so they could discuss them on the phone:

If either one of them ever wanted to end the affair, for whatever reason, it would end. No questions asked.

If either one became too emotionally involved, the affair would end.

If they ever started taking risks that shouldn’t be taken, the affair would end.

All expenses—food, motel room, gasoline—would be shared equally.

They would meet only on weekdays, while their spouses were at work.

Candy would be in charge of fixing lunch on the days they met, so that they could have more time. They figured they would need all of Allan’s two-hour lunch.

Candy would be in charge of getting a motel room, for the same reason.

They would meet on a Tuesday or a Thursday, once every two weeks. That was because Candy was free only on days when her little boy attended the Play Day Preschool at Allan Methodist Church. She took him each Tuesday and Thursday, from nine to two, but she figured that she would need three out of four of those school days for all the other errands and church and school duties in her hectic schedule.

Finally having checked off every possible precaution, like astronauts getting ready for a launch, they set the date for the affair to begin: December 12, 1978.

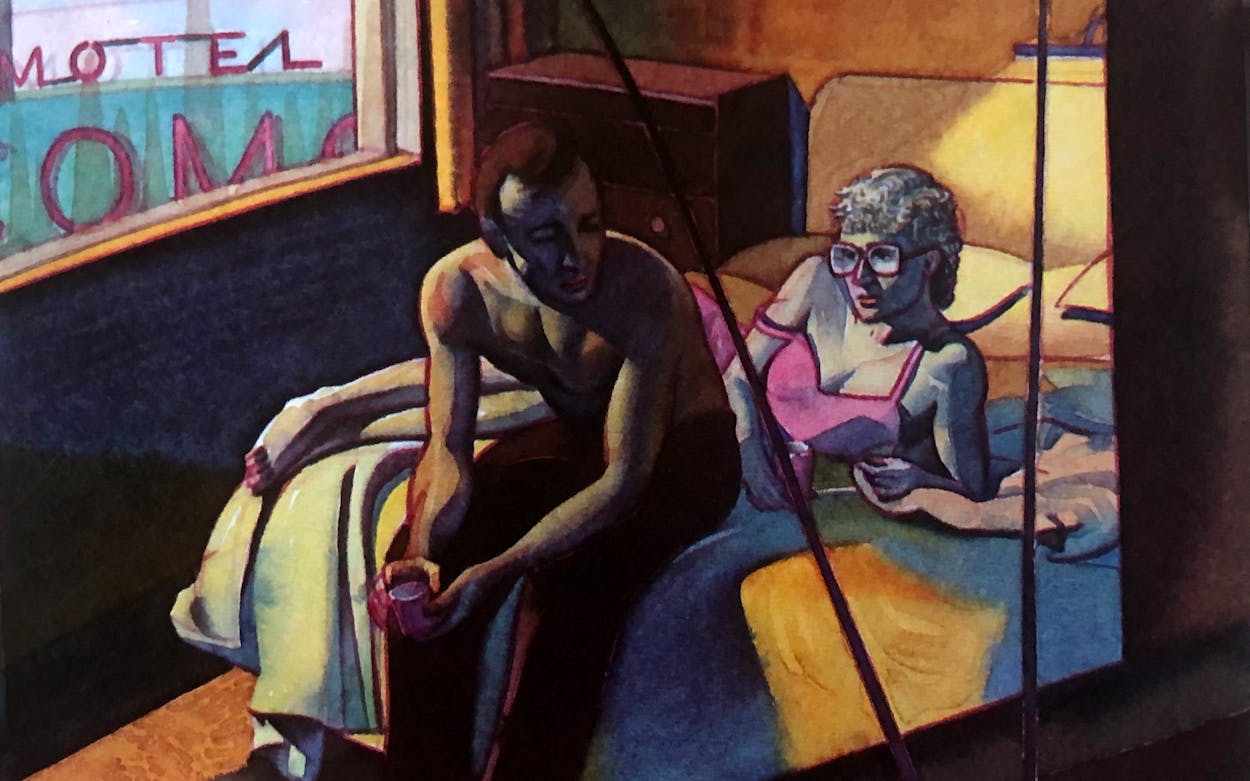

Love at the Como Motel

Candy spent the morning getting ready. First she dropped off her daughter at the little red Lovejoy schoolhouse on FM Road 1378, then she went on to Allen and deposited her son at the Play Day Preschool. When she got back to the house, she allowed herself about an hour to fix the special lunch she had planned: marinated chicken, lettuce salad with cherry tomatoes and bacon bits, Thousand Island dressing, white wine, and cheesecake for dessert. She packed everything, including a tablecloth, into a picnic basket and then gathered together a few undergarments and a nightgown and slipped them into her purse. She had everything ready by ten-forty-five. By eleven she was entering Richardson in her station wagon, searching for a motel convenient to Allan’s office. She found one right on the freeway, just two or three minutes away from Allan, called the Continental Inn.

It took a few minutes to check in because the girl behind the counter insisted on seeing her driver’s license and getting the money in advance. Candy paid out $29 of the cash she had gotten at the supermarket the day before and then filled out the registration card with her real name. The girl gave her the key to one of the upstairs rooms set back from the highway. Candy drove the station wagon around to the back and started unpacking.

The room would do nicely. It was about ten by twelve feet, with one of those old televisions about the size of a Buick. The walls were covered with bright yellow fake paneling, which perfectly fit the autumnal décor: old brown carpet and, on the bed, a spread adorned with leaves and pinecones. Candy went straight to the phone and called Allan at work. “I’m at the Continental Inn on Central Expressway,” she said. “Room Two-thirteen.”

“Be there in a few minutes,” he said.

Candy busied herself getting the room ready. First she arranged her marinated chicken feast on the bed. Then she slipped into her favorite peekaboo negligee; it was a soft pink color and almost, but not quite, sheer. It was long, falling all the way to her ankles, and it showed off her body while hiding the slightly too large thighs. She looked at herself in the mirror. For a mother of two, she didn’t look bad. Then she sat in a chair by the window and waited.

Suddenly, for the first time since she had propositioned Allan in the church parking lot, Candy started to get nervous. Perhaps it was the coldly impersonal room, perhaps the calculated way they were going about the affair. But she felt herself becoming frightened now that she realized that whatever they did today would be irrevocable. Everything she had done before, no matter how brazen, had been harmless flirtation compared with this. Having sex is not as simple as it seems. It changes people.

On the way to the motel, Allan discovered that he wasn’t quite as brave as he had thought, either. He worried that perhaps the only reason he was doing this was to please Candy. He had to admit that Candy was sexually appealing, and yet he didn’t want to be full of anxiety all the time. He didn’t want to feel the way he was feeling now.

But once he opened the door and saw Candy, smiling and seductive in her pink nightgown, Allan felt a surge of bravado. “What the heck,” thought Allan. “I’m here, and I’m going to do it.”

“I’ve made lunch,” she said, smiling halfheartedly. Allan could tell, much to his surprise, that Candy was even more nervous than he was.

They sat on either side of the bed and made small talk. Allan dug into the chicken and quickly drank a glass of wine. Candy poked at her chicken, tearing off one little sliver at a time. “I feel like what we’re eating,” she said. Allan smiled.

They finished off the dessert and then busied themselves with putting aside the paper plates and containers, as though neither wanted to make the first move. When there was nothing left to do, Candy sat quietly in the chair by the window. There was a moment of strained silence.

“Well,” said Allan, “are you just going to sit there?”

Candy smiled. “Yes.”

Allan walked around the bed and gently touched her on the shoulder. All of her nervousness dissolved.

The sex was gentle and conventional and satisfying. It was also brief. Candy was amazed at first by Allan’s naïveté as a lover. When she stuck her tongue into his mouth, it was apparent that he had never had a French kiss before. The good news was that he was a quick learner. For his part, Allan was positively transported. Candy was so responsive and energetic—she moved so much—that Allan found it more exciting than any sexual experience he had ever had. It was good for him because it seemed so good for her. He couldn’t keep going very long, but he remembered the feeling for days.

Afterward Candy insisted they both take showers before leaving. “So you won’t smell like me,” she said.

Candy felt well pleased. Despite Allan’s apparent inexperience, she hadn’t had to fake her responses much at all. And he did show great promise as a lover. Allan was just as satisfied by the lunchtime rendezvous and was looking forward to the next one. When he went back to work, he felt weak the rest of the afternoon.

After the first meeting at the Continental Inn, it was obvious that both of them would want more. So a week later, just before the Christmas holidays, they arranged by phone for a repeat performance. This time Candy spent the morning preparing teriyaki beef strips and cheese blintzes. She did change one other detail. When she got to Richardson, she noticed a smaller—and sleazier—motel across the freeway from the Continental. Always the practical shopper, she figured a motel room was a motel room, so why not get something cheaper than $29?

The Como Motel was quite a comedown, even by the less-than-luxurious standards of the Continental. Candy got the impression that the Como didn’t have a lot of overnight visitors when she walked into the office and came face to face with a clerk standing behind a Plexiglas screen, like a bank teller’s window or, perhaps more appropriate, a jailer’s. The manager wanted $23.50 cash in advance plus a $2 deposit for the key. Candy put her money in the trough under the window, and he passed her a key. She drove around to the asphalt lot in the back.

In the months to come Allan and Candy would joke about their room at the Como. Candy always said it smelled like old money. The sleaziness of the place was what made it so illicit—and so much fun. The room was little more than a cubicle, ten by ten at the most, done in a tattered harvest gold. The curtains were drooping and frayed. The shag carpet was matted like dirty hair. The bathroom had fake terrazzo flooring, the faucet leaked, and the only furnishings other than the bed were a tiny vanity, a TV set, and two captain’s chairs with imitation leather cushions.

Here, for the last days of 1978 and the first three months of 1979, Allan and Candy made glorious love every other week, dined on taco salad and homemade lasagna, and sipped cheap red wine out of plastic cups supplied by the management. (They came wrapped in cellophane bags with Walt Disney cartoons on them.) Afterward they would recline on the bedspread and rest their heads on tiny foam-rubber pillows and talk about their lives and their spouses and their children and their mutual love for their church. They would talk until it was time for Allan to go back to work or for Candy to pick up her son, and then go stand in the tub and turn on the faulty shower attachment and wash off the smell of each other. Finally, they would gather up their belongings, kiss each other lightly on the lips, and go back to their normal lives, closing the door behind them.

Later, when Allan looked back on his whirlwind lunch hours with Candy Montgomery, he would think less of the sex than of the relaxation he took there. Those two hours with Candy were often the only time he didn’t feel responsibility for other people’s emotions, the awful burden of making Betty happy. In the confines of a room at the Como Motel, Allan was a man with no past and no future, able to accept Candy’s unconditional affection—she showered him with it—in a way that was simple and guiltless. Allan had never been with any other woman except Betty in his life. This experience was revitalizing in a way that his life with Betty hadn’t been for a long time.

The affair made Candy feel alive again too. She was excited about the sex and the intrigue and the adventure of it all, and she continued to see Allan every two weeks, like clockwork. Unfortunately, after the third or fourth time at the Como, she started to have second thoughts. Her doubts weren’t spurred by any feelings of guilt. They started, in fact, when she realized that sex with Allan Gore probably wasn’t going to get much better than it already was. The first two or three times it had felt good, but there had been virtually no improvement, and she suspected that the man was not capable of fireworks, no matter how much she coached him. The more serious problem was that Candy feared she was beginning to like Allan too much. Sometimes she even thought she loved him. That was too risky.

In retrospect, she would see that it had been inevitable. Sex or no sex, she and Allan had both come to look forward to their daily conversations, their shared confidences, their joint dependence. Lately they had been exchanging funny little greeting cards, and whenever Candy had to drive into Richardson on an errand, she would stop at Allan’s office and place gifts under his windshield wiper. Sometimes Allan would go out to check his car even when he was staying for lunch, just to see if he had any brownies or homemade candy waiting for him. Once he found a small ceramic statue of a boy and a girl kissing. The inscription on the base read, “Practice Makes Perfect.” As time went on they seemed less like lovers and more like best friends. During one rendezvous, they decided to forgo sex altogether because they wanted to spend lunchtime talking. Candy could even talk to Allan about Pat; he was that understanding.

By February, after only two and a half months, she was more than a little anxious that the relationship was turning serious all of a sudden. One day at a lunch she tentatively broached the subject with Allan. “I think I’m getting in too deep,” she said.

“What do you mean?”

“I don’t want to fall in love with you. We’re getting serious, and I know this is a temporary thing. I don’t want to have to deal with myself later if we go too far.”

“How do you know this is getting too serious?” asked Allan.

“I think of you too much.”

“But I thought you were the one who said you’ve got to plow into life and see what happens.”

“That’s right, I did say that.”

“Well?”

“I guess I’m caught in my own trap.”

“It won’t get too serious if we don’t let it get too serious. I think the relationship is temporary, too, but we’ve got to let it run its course.”

“Well, if you’re not too worried about it, I guess that makes it half all right.”

Eventually Candy allowed herself to be talked into going on, mostly because she didn’t like the thought of not talking to Allan, and she was afraid they wouldn’t be able to continue their friendship without sex. It helped that she and Pat were planning a long vacation to visit her parents in Georgia; that would give her most of April to sort things out and discover how she really felt about Allan.

Allan doubted that he was capable of falling in love with Candy, but for the time being he needed her. They had something special, something that was renewed each time they caught each other’s eye during a church service or touched hands over a table at lunch or did something as simple as wasting time on the phone. Allan felt better about himself. He didn’t want this affair to get out of hand, of course, but so far he was surprised at how little it had changed the rest of his life. If anything, it made everything a little easier. Even going to church was easy, and at first he hadn’t expected to be able to do that. He still liked Pat. He didn’t think he was doing anything to hurt him. There was no change in his relationship with Betty. Who knew where this affair would end up or how long it would last? But in the meantime he was enjoying it, and he couldn’t see how anything very bad could result from it.

After Candy left for Georgia, Allan missed her and wondered briefly whether her feelings would change while she was away, but also he felt a sense of relief. He hadn’t realized, until he had a few weeks off, how much work an affair could be.

Allan needn’t have worried about Candy changing her mind. When she returned from vacation, it was obvious that she had missed him as much as he missed her. They made a date for the Como, but after the lunch and sex, they spent most of their time catching up on each other’s lives. One thing they talked about was Betty’s pregnancy. Betty was seven months along, and Allan was getting a little apprehensive. Betty would need lots of attention as the day drew closer, because of her problems with the first baby. And it had crossed Allan’s mind that if Betty started having labor pains when he happened to be at the Como, he would never be able to forgive himself. In early June he told Candy he thought they should discontinue the affair for a while so that he could be available for Betty at all times. Candy agreed completely. Allan loved that about Candy; she understood things like that. Betty would have disagreed and whined, especially when something she wanted was threatened. Sometimes Allan wondered what it would be like to be married to Candy. But then he thought, “No, that was out of the question.” He knew that he’d never divorce Betty, no matter what.

Allan couldn’t have realized, and Candy didn’t tell him, that she was more than willing to suspend the affair for a while, and it represented no big sacrifice on her part. The last visit to the Como had confirmed her earlier fears: the sex was not that great. They spent so much time talking that the physical part was all but obligatory. She would never say so, but Candy was also tired of getting up early on the days they sinned together, so she could make beef chow mein, cream puffs, and ham-and-cheese casserole. Allan had come to expect notes and cookies and things left on his car too. The whole thing was becoming a hassle. She missed the magic of those first few weeks.

At times Candy would admit to herself that she felt guilty about Pat. He was oblivious to everything. She was certain he had no suspicions about her and Allan, even when they exchanged glances during worship service. Nevertheless, sometimes it was hard to be around Pat, just because he did trust her so much, and it didn’t make it any easier when Pat would tell her how much he liked Allan.

Candy’s powers of deception were put to the ultimate test in mid-June when she threw a sit-down Chinese dinner for the choir. The real purpose of the dinner was a surprise baby shower for Betty Gore. It was Candy’s idea. She thought it would be fun. It didn’t occur to her that it might be awkward, since she had never felt uncomfortable around Betty, even when she was sleeping with Allan. Someone fixed a special cake, everyone brought gifts, and Candy turned out to be right: nobody felt uncomfortable, not even Betty. She beamed with pleasure—it was one of the few times, in fact, that she seemed completely untroubled and at peace with herself. She was almost one of the girls.

Betty’s First Advance

Bethany Gore was born in early July, and Betty seemed to perk up for a while. As babies often do, Bethany brought her parents closer together, especially during the week just after she was born, before they told anyone in the church about her.

The feeling didn’t last long, though. Now that Allan didn’t need to be on call all the time, there was really no reason for him to put off the affair any longer. But when he and Candy renewed their lovemaking at the Como in late July, it seemed different, lackluster. The sex was still good, Allan thought, but Candy was more reserved than usual; a couple of times she griped at him about little things that didn’t matter, and that wasn’t like her at all. There was something else, too: for the first time, Allan was feeling guilty. He thought of Betty back at the house, taking care of Alisa and Bethany by herself, and he didn’t feel good about himself. That week after the baby was born had been something special. He wondered if there was a way to get it back. He hoped he wasn’t making that impossible by continuing to see Candy.

Allan was grateful when Betty finally felt well enough to travel, because that meant they could take off a week to show the baby to her anxious Kansas grandparents. He wanted to be away from Candy for a few days, but he wasn’t prepared to tell her that. Before Allan left, they agreed to meet at the Como on the following Friday, since Candy knew she could get a sitter that day.

The Gores didn’t arrive home from their Kansas trip until late Thursday night, and ordinarily Allan would have taken off work on Friday as well. But he knew that Candy really wanted to see him that day. If he didn’t go to work and she ended up at the Como by herself, the fallout would be disastrous. But when Allan told Betty he intended to go to work on Friday, she objected, arguing that he should stay home and help her with errands. Not only was she insistent that he stay home, she was more than a little suspicious about why he just had to go to work. So Allan cooked up an excuse to call Candy—something to do with church—and then he phoned from the kitchen while Betty was in the master bedroom at the back of the house. Without actually saying the words, he got the message across that he couldn’t make it. Candy grew angry when she realized what he was telling her, because now she and Pat were leaving for a week-long vacation and that meant she wouldn’t see Allan for another two weeks. Allan didn’t want to hang up while she was mad, so he stayed on the phone a few minute, hoping she would calm down. When he hung up, feeling depressed and sheepish, he walked back to the bedroom.

“Gee, that sure was a long conversation,” said Betty.

Candy and Pat spent the next week in Wichita Falls, and the following Friday she met Allan at the Como Hotel. It was late when he got back to the office.

That night Betty wanted to make love. The Gores hadn’t had sex since the baby was born, at first because Betty didn’t feel up to it, later because they were simply out of habit. Allan had become so desultory about making love to his wife that they were having sex no more than once a month. But the odd thing about that night was that Betty was so aggressive. It wasn’t like her. Allan couldn’t remember her ever taking initiative before, in all the years they had been married. But Allan had been with Candy a long time that afternoon, and he was spent. He was so surprised by Betty’s sexual advance, though, that he couldn’t think of an excuse. He just said he didn’t feel like it.

Betty began to cry. She was embarrassed and humiliated and deeply hurt. It would have been different if she were in the habit of making advances, but to have the very first one rebuffed was too much for her. She jumped to conclusions. Allan didn’t love her anymore. He hated her because she was fat after having the baby. Allan tried to reassure her, but nothing worked. She had been rejected, and she couldn’t stand it.

On Monday morning, Allan phoned Candy. “I need to talk. When can I meet you and where?”

They arranged to meet for lunch, and Allan poured out the whole story of that Friday night. “Betty was very upset,” he said. “She kept saying, ‘You don’t love me anymore, you don’t love me anymore.’”

“You did reassure her, didn’t you?”

“Yes.”

Candy began to cry. “I think that’s a little unfair of Betty, to say a thing like that after you can’t perform one time.”

“It upset me too. It was just that she made the first move.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I think maybe we should end it.”

“Now you’re being grossly unfair.”

“I’m afraid of hurting Betty. I think maybe the affair is affecting my marriage now, and if I want to get my life back in order, I have to stop running between two women.”

“But what about when I suggested we end it? Remember what you said then? You said, ‘No, you have to see this through to the end,’ and ‘Just because something happens once doesn’t mean it will happen again,’ and things to that effect. Now that you can’t perform with Betty one time, suddenly you want to end it. That’s a double standard.”

“I’m not saying we should definitely end it. I’m just saying we should think about it. I don’t want to hurt Betty.”

The issue was left unresolved after the lunch meeting, but they talked several times by phone over the next few weeks. Each time Candy grew colder and more antagonistic; she couldn’t bear the thought of Allan’s having so little regard for her feelings. But then she would cry and feel better and tell him that she loved him.

“I do love you, Allan.”

“I know, but we’ve become too close. We’ve become so close that I’m afraid I don’t love Betty anymore, and that was never a part of our agreement. We’ve both been using each other to fill gaps in our marriages, and that’s not right.”

“It’s just so unfair.”

After the Friday-night incident Betty Gore fell into a deep despondency that lasted several weeks. At first Allan thought he could talk her out of it by spending more time with her. But soon she was complaining of soreness in her neck and shoulders and sudden pains. She was sullen and depressed much of the time, especially after she returned to teaching in early September. She started seeing her family doctor again, and he prescribed pain pills to alleviate some of her complaints. Privately he suspected that the ailments were all stress-related.

Later that month Allan satisfied an old ambition of his and quit Rockwell International to join a tiny new company called ECS Telecommunications. The company had only one product—a telephone answering system—but Allan had good friends there, former Rockwell employees who dared him to take a chance with a small, ground-floor firm. The only way Allan could have advanced at Rockwell would have been to take jobs that required extensive travel—out of the question, given Betty’s fear of being alone. ECS was offering more money and stock besides. The job was exciting and something that Allan really wanted to do, if Betty would go along. It took a while, but he convinced her that the move wasn’t too risky, that he wouldn’t be spending more time at work than he was now. Betty reluctantly agreed—if she hadn’t, Allan wouldn’t have done it, because he wouldn’t have been able to stand the complaining—but she remained fearful and nervous, as she was about any new venture.

The next time Allan talked to Candy, he said that because of the new job and the additional work, he wouldn’t be able to see her as much. Candy was upset; she was beginning to fear the inevitable end of the affair. But she asked Allan if they couldn’t meet at least once more. At the Como they had quick, unsatisfying sex, then spent an hour and a half discussing how they could live without each other. Candy was clearly having second thoughts about breaking off the affair; she had grown too dependent on Allan’s kindness. The next time they met, they didn’t bother to go to the motel. Instead they took their picnic lunch to a park in North Dallas and spread their blanket under a tree. The weather was so nice that it gave a bittersweet aura to the conversation.

“I love you so much, Allan. I don’t know if I can make it if we break up.”

Allan didn’t know what else to say, except the usual things about wanting to patch up his marriage. “Betty wants to go to Marriage Encounter now. I asked her once before, but she always said she didn’t think we needed it. I think maybe it will do us both some good.”

“I think Marriage Encounter is going to be the end for us,” Candy said.

“Oh, no, not necessarily. Let’s see what happens first.”

Two weeks later Betty returned to her doctor’s office, extremely tense and complaining of aches and pains in her shoulders. Her blood pressure was dangerously high. The doctor prescribed more pain killers and muscle relaxants and asked her to come back in a few days. Betty felt a little better after talking to the doctor. What she didn’t tell him was that all of her anxieties were centered on the coming weekend: she and Allan were about to be “encountered.”

“Why Did I Come Here This Weekend and What Do I Hope to Gain?”

Dunfey’s Royal Motor Coach Inn, a fake medieval castle full of tunnels and turrets and gables and the regal purples and scarlets of an Adult Disneyland, was the site each month of the weekend gathering called Methodist Marriage Encounter. It was less a counseling session than a total-immersion experience. Though it had the tacit approval of the church, it was run by laymen. It began with a Friday-night dinner at which the rules were explained. Spouses were to be at each other’s side at all times. Televisions were not to be turned on in the rooms. Newspapers were forbidden. Nothing was to get in the way of the couples’ communicating about their feelings.

“Communicating” and “feelings”—those were the watchwords of Marriage Encounter, as Allan and Betty found out soon after arriving into room 321. They were led into a large meeting hall, with three dozen or so other couples, and introduced to their Encounter leaders, all married couples who had previously gone through the program. The couples onstage would talk openly about their marriages, but no one else was to speak except in the privacy of their motel rooms. The procedure was that the leaders would propose a question—the first was, Why did I come here this weekend and what do I hope to gain?—and then the couples would retire to their rooms to write answers in their individual Marriage Encounter spiral notebooks. (Below the Marriage Encounter insignia on the cover was the Bible verse, “Love one another as I have loved you.”) Once they had written their answers, they exchanged notebooks “with a kiss,” read each other’s answers, and then discussed how those answers made them feel. When their time was up, they would be summoned back to the main room for more testimonials, followed by additional questions. The group leaders gave them printed sheets explaining “how to write a love letter,” “how to dialogue,” and “what is a feeling?” and assured them that everything written in the notebooks would be strictly private.

Allan and Betty, like most couples entering the program, were skeptical at first. It sounded silly, writing things down in a notebook. But they had no choice in the matter. That’s what they were told to do. They were sent to their rooms. They began to write. Allan didn’t know what to put down. Finally he wrote: “I wanted to come here because I see from [our friends’ examples] that it could strengthen or rebuild a marriage. I think too that I haven’t felt real close to you for some time and I don’t like that. I hope I can learn to talk to you. I hope you can learn to talk to me. I want to be able to understand why you do the things you do, and I want to be able to tell you what I want.”

Betty was more specific: “I came for several reasons. First—for a weekend of relaxation which will probably help my nerves…Second—and most important to get off by ourselves together…I’m not a person to be left alone at all. I want my husband with me and that’s what we’ll have this weekend —just us!!

“I hope to gain a little more freedom in expression between us. I don’t often hold back my feeling unless I’m mad—then not for long but I feel that sometimes you don’t let me know when things are bothering you. We need to work on this!”

As they read over their answers and then discussed what they had written, Allan was pleased to see that Betty really was responding to this program. After a few minutes, one of the group leaders came by and knocked on their door. It was time for the next session.

Called Focus on Feelings, this session was more personal. The couples were given three questions: What do I like best about you and how do I feel about that (or HDIFAT, one of many official Marriage Encounter abbreviations)? What do I like best about myself and HDIFAT? What do I like best about us and HDIFAT?

Suddenly the Gores were in a realm that brought out emotions Betty had never expressed before. To the first question, she wrote, “The thing I like best about you is your calmness and your ability to look at everything squarely. You don’t know (or maybe you do) how this affects me…You’re my tranquilizer.” Her final answer—what she liked about them as a couple—was “that special feeling I get when we’re together…Warm and happy—It’s horrible when we’re not—it’s like I’m only half of me—maybe that means I’m not secure enough. I don’t think so—your presence is just important to me.”

Allan’s answers were much more prosaic. He liked Betty’s “dedication to raising the children and [her] job.” He liked himself for his calmness and rationality. He liked them for their “promising future.” He felt “secure, but not totally fulfilled yet.”

The encounter session was in full swing Saturday, and as the day wore on, through meals and pep talks and instructions on how to DILD (describe in loving detail) or “share our uniqueness” or “open up the gift of dialogue,” and as the questions got progressively more personal and incisive, the group took on all the appearances of a love-in. Encouraged to show affection publicly, couples started emerging from their rooms with arms entwined, holding hands during the meeting room sessions, and exchanging light kisses at meals. Everyone was issued a name tag. Allan’s read “Allan and Betty Gore.” Betty’s read, “Betty and Allan Gore.” The couples were encouraged not to carry on any conversations with others without including their spouse entirely. Given the total immersion, the lack of outside influences, the complete concentration on one person for an entire weekend, it wasn’t surprising that remarkable things were happening. Allan was beginning to realize why couples who emerged from Marriage Encounter were likely to become evangelists.

During their time together in room 321, Allan and Betty were certainly starting to feel closer. When the couples were asked to write a “Love letter on feelings of disillusionment,” the dike gave way for Allan: “I have feelings of boredom, emptiness, and sort of loneliness. I don’t really know why, but I do. I don’t feel like I really know what makes you happy, and that’s frustrating…Sometimes I feel like what is most important to you is your classroom—not me. That may not be true, but sometimes I feel jealous of that classroom.”

Betty’s “love letters” on Saturday began with a confession of her shortcomings (“I wear the mask of the ‘Do it all’ person”) and led up to her most deep-seated fears. “So many times,” she began in one letter, “I feel that sex is an area that we are a long way apart. I guess part of it is the way I was brought up—sex is dirty and wrong—and for a long time the fear of becoming pregnant when I didn’t want to be…I want to be desirable to you—and I want to make you happy.”

In response to another question, she touched on an even more specific anxiety: “It’s hard for me to talk about sex too (more of the upbringing stuff). Sometimes it’s so hard to feel calm and quiet as you need to be to enjoy sex. I guess the relaxation part is the hardest for me. That’s why in Switz. a little (or a lot) of wine helped. It relaxed me so I could really be free to enjoy it all. I’ve tried several times to have some but what we’ve gotten tastes bad, or Alisa’s up, or it’s a school night etc. There’s always a drawback. Does this mean I’m not comfortable with sex if I need wine to make love more pleasant? I don’t know.”

When the sexual topics showed up in Betty’s letter, Allan was unable to respond. How could he tell her that one of the reasons he didn’t want to have sex as much anymore was that he was sleeping with Candy? The weekend was supposed to bring about total honesty, but that was one detail he did not intend to reveal. When they went to bed Saturday night, exhausted from the long day, they made love—and Allan could tell that the weekend was going to be good for both of them.

Sunday is the final and the most special day of a Marriage Encounter. It begins with religious services followed by more group sessions, and then each couple is given a mimeographed sheet. On it is the big question of the weekend, What are my reasons for wanting to go on living? The couples retire to their rooms for ninety minutes of writing in their notebooks and ninety minutes of dialogue—a total of three hours for what is called the matrimonial evaluation. It’s intended to bring out the emotions that have been building throughout the weekend. After the Go on Living session, couples frequently emerge from their rooms with tearstained faces and tousled hair. In the case of the Gores, it was an engrossing—and satisfying—experience. They declared their love over and over, in letter and the dialogue. Allan wrote: “Before this weekend…I was beginning to feel like I didn’t know if I really wanted to live with You. But just in the short time we’ve had together this weekend, I have realized that what I was feeling was not ‘I don’t like you’ but more like I don’t feel excited about you because I’m too used to the way things are…I want to share a lot more of your feelings and I want to be able to share mine with you.”

Betty was equally warm, but at the end of her letter, she turned solemn: “Here I sit crying because I am so happy and so proud to be your wife. I’ve known that all along, but when you really stop to think about it we are so lucky to have each other. Let’s don’t let anything come between us. We’ve been through so much, all of it we can look back at as good (except the times you were gone for a long time.)…I remember those times with dread. The aloneness, the coldness of a house that really wasn’t a home without you there, the fear for your safety, because you were where I was not, and I couldn’t make sure you were okay. I never really felt fear for my safety at home alone, but the feeling of being alone is the worst possible one to have. It’s like you’re in a dark tunnel and you’ve got a long ways to go to the light. The light isn’t there till you’re home again safe and sound.”

That night Allan and Betty emerged from room 321 for the final time, and the group gathered to celebrate the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper (using a modernized text). The couples sipped the communion wine in the Marriage Encounter fashion, with arms linked. Afterward, in the emotional climax, they were all remarried in a ceremony in which they led each other through the traditional vows. Many of their “encountered” friends surprised them with their presence at the ceremony, and others sent their love through greeting cards congratulating them on their new commitment. When the Gores got in the car to go home, the radio happened to be broadcasting the wrap-up show for the Dallas Cowboys game. Allan switched it off; it was just noise to him, part of a past life. When they got home that night, they fielded calls until bedtime, all from joyful well-wishers soon to be part of their “flame group” (as in “Keep the flame burning”), which would meet regularly to keep the spirit of fellowship alive.

The Gores ran one errand before they returned to Wylie, though. They stopped by the Montgomery house in Fairview to pick up Bethany, whom Candy had kept for the weekend. Allan went to the door while Betty waited in the car.

“How was it?” asked Candy as she handed him the baby.

“It was really good for us.”

“What does that mean?”

“I don’t know.”

The next morning Allan was still riding the emotional high as he dressed for work. On the drive into Richardson, he tried to shut out all sensations except thoughts of Betty. His life had changed. He wanted to concentrate all his thoughts and feelings on his marriage, which was once again the most important thing in his life. Yet when he got to work, he knew that sooner or later he would need to call Candy. She would want to meet him for lunch. He had to face that squarely.

They met a week later; she brought a picnic lunch and they went back to the park in North Dallas. Allan did most of the talking. He told Candy all about Marriage Encounter and what it had done for them. “We learned a lot about each other,” he said. “I think maybe I was wrong about Betty in some ways. I think a lot of the things she doesn’t like about me were based on fears of loneliness instead of bitchiness. We told each other things that we hadn’t even thought about.”

“That’s good,” said Candy. “I’m glad.”

“I don’t necessarily feel different about you,” said Allan, “but I do feel strongly that I want to give my full resources to my family. The relationship with you is taking away some of the emotional involvement and energy that I could direct toward Betty and the kids. I’m not sure how long this feeling will last or what will happen, but I know I don’t want to interfere with it.”

“What does that mean for me?”

Allan suddenly had no desire to go to bed with Candy again.

“I’m not sure I can deal with not seeing you,” said Candy.

After making the strongest argument he could for breaking up, Allan still couldn’t bring himself to say the words. They left the issue hanging but agreed to meet again the next day. When they did, Candy came directly to the point. “Allan, you seem to be leaving it up to me. So I’ve decided, I won’t call. I won’t try to see you. I won’t bother you anymore.”

They both cried a little because they knew it was over. Allan was secretly relieved that she had made the decision, not him. That way he didn’t have to bear the guilt. He hadn’t planned for it to happen that way. That’s just how it worked out.

Candy had mixed emotions as well. She was telling the truth when she said she didn’t know how she would deal with the loss of Allan. She had grown comfortable with the idea of loving two people. She loved Allan’s casual phone calls and small kindnesses, and she would miss them. The good news was that she didn’t have to make any more damned picnic lunches.

A short while later, Candy and Pat attended a Marriage Encounter session. Though they enjoyed it, they did not have the kind of life-changing experience that Betty and Allan had had. But both couples headed into the summer of 1980 with a sense of peaceful happiness about their lives. That would soon change.

Continued in Love and Death in Silicon Prairie, Part II: The Killing of Betty Gore. These pieces have been drawn from the book Evidence of Love, published by Texas Monthly Press.