I. THE DARKEST PLACE IN ELLIS

On November 9, 1967, Fred Cruz was in his sixth year of a fifteen-year robbery sentence and starting yet another stint in the hole. Of the many punishments the Texas prison system doled out to inmates, solitary confinement was one of the most brutal on the body and the soul. It wasn’t Cruz’s first time there, but it wasn’t something one got used to. The Ellis Unit, about fourteen miles north of Huntsville in a boggy lowland area of East Texas, was known as the toughest prison in the system, and there was no worse place to be in Ellis than solitary.

The cell’s darkness was so complete it made the eyes ache. On some occasions, Cruz was given a thin blanket and nothing else—no clothes and no mattress for the steel bunk. His toilet was a hole in the floor. He’d receive only three slices of bread a day with a full meal twice a week, and had shed multiple pounds from his already thin frame. After two weeks, an outer door to the cell would be opened, allowing in light from the hallway. This would be considered a “release” from solitary. Then the warden or an officer would come by and assess the sincerity of Cruz’s contrition. If he failed that yes-sir-no-sir encounter, the solid steel door would be shut again and the days of darkness would recommence.

Cruz’s ability to maintain his composure through interminable silence and darkness was better than that of many other inmates, but still uneven. Sometimes a panic would rise in his chest, his heart would pound, and he couldn’t catch his breath. Some days he simply wished for death.

But if he got his mind right, he could keep it together. Cruz’s upbringing had made him tough. Abandoned by his father, he came of age in the late fifties and early sixties in the segregated Mexican-American barrios on the West Side of San Antonio. It was a place where you joined a gang or risked becoming a victim. He ran with the Mirasoles and dressed in street pachuco style: zoot suits with pleated pants and suspenders. Members of his family sold drugs, and run-ins with the law were a regular occurrence. Cruz was nineteen and serving a short stint for selling marijuana when he learned that his older brother Frank had been shot dead by the police during a failed hold-up.

From that childhood grew an emotional steeliness, but it wasn’t until he started this fifteen-year stint in 1961 for robbery that he began to develop an intellectual and a spiritual strength. He took to reading difficult texts in philosophy and legal theory. He learned about yoga and Eastern religions, and started a correspondence with a Buddhist priest in San Francisco. It was the sixties, and though he was in prison, Cruz was aware of the cultural awakenings happening in the world around him. He read Joseph Campbell’s The Masks of God and Rammurti Mishra’s Fundamentals of Yoga. He was drawn to the Buddhist idea that peace of mind came not from the external world, but from personal insights into truth and reality.

Insubordination

That morning’s “infraction” had been stupid and petty. As Cruz’s squad prepared for the short journey to the cane fields, a friend had offered him a seat on a work wagon. A prison guard, Officer Graham, told Cruz to get on a different wagon, which he promptly did, although he couldn’t help making an offhand comment. “Personally,” he said, in his quiet but steady cadence, “I’m not particular about which trailer I go to work in.”

Cruz’s response might have sounded innocuous to anyone not schooled in the subtextual game of prison obedience and resistance. But any prisoner who heard the comment certainly knew it was a brazen challenge to the guard’s authority.

“You’re not going to take over my squad,” Officer Graham yelled at Cruz. “You aren’t going to run anything while you are working under me!”

That evening, after a full day of cutting cane and the open-air strip search that was required after prisoners used any tools, Cruz was called into the major’s office, where he found almost the entire prison hierarchy waiting for him, including Officer Graham and Assistant Warden McKaskle.

“What’s your trouble?” began one of the captains.

“I don’t know, sir,” said Cruz. “That’s what I’m here to find out.”

“Well, you’re sure fixing to find out right now,” said the captain. Then, Officer Graham told his story about Cruz getting on the wrong wagon. Cruz, he said, had been “running his head with them others. I told him to get off my trailer, and he opened his mouth to me.”

Captain Ramsey announced the penalty: “That will be one gallon of peanuts.” Shelling peanuts was at the low end of the punishment scale, a nasty, mind-numbing task that would keep Cruz up half the night and leave his fingers blistered and raw.

“Just a minute,” said Cruz. “Don’t I get to say anything at all?”

“Sure,” McKaskle said. “You got anything you want to say?”

He could have let it go right there and just taken the punishment. He knew that if he objected things would only get worse. But it wasn’t in Cruz’s character to let things go, and he bridled at arbitrary rules. So he launched into his defense, speaking slowly and looking his accusers in the eye. Many who guarded or served time with him would remember his preternatural calm. Even when being interrogated or brutally beaten, he stared out at the world as if nothing could surprise him, as if his true self had receded deep inside to watch events unfold from a distance. Cruz was only 27, but he had the sort of inner strength that could unnerve those charged with keeping him in line.

A page was added to Cruz’s folder of offense reports, a file that was already thick enough to make a thump when dropped on the warden’s desk. The new entry read: “Insubordination—refused peanuts.”

Cruz asked the men to tell him exactly what prison regulation he’d broken. Was there a rule about which work wagon he rode on or whom he sat next to? “I’m entitled, under your rules, to a fair hearing,” he told the group. “I’m refusing to go along with the recommendation at this time. I wish to appeal the decision of this committee to the prison board.”

“Very well,” said McKaskle. “You may do that when you are released from solitary.”

And so another confrontation with authority came to a close. A page was added to Cruz’s folder of offense reports, a file that was already thick enough to make a thump when dropped on the warden’s desk. The new entry read: “Insubordination—refused peanuts.”

Many of the other offenses chronicled in that disciplinary file were just as petty. Cruz had only recently been transferred to Ellis from another prison when he drifted away from his squad’s cotton row. For that, he had lost ninety days of “good time.” (Accruing good time allowed prisoners to take as many as two days off their sentences for every day they kept their noses clean. But looking at a guard sideways could be enough to wipe those “good time” days away.) On another occasion, while picking cotton, Cruz had asked a guard for water with the words “no water, no work.” For that he received a week in solitary. Then there was the time he received the punishment of standing on a rail, which meant standing for days at a time on a six-by-two plank turned sideways. The offense that day: “inmate started chasing an armadillo.”

The infractions went on and on: “unsatisfactory work” … “creating a disturbance” … “impudence” … “refusal to work” … “disobeying a direct order” … “disrespectful attitude” … “insolence” … “insubordination” … “insubordination.”

Cruz always lost, but with each encounter he learned a little more about the nature of the Texas Department of Corrections. He learned it the same way someone can learn a great deal about the nature of a grizzly by poking it with a stick.

Finding the Law

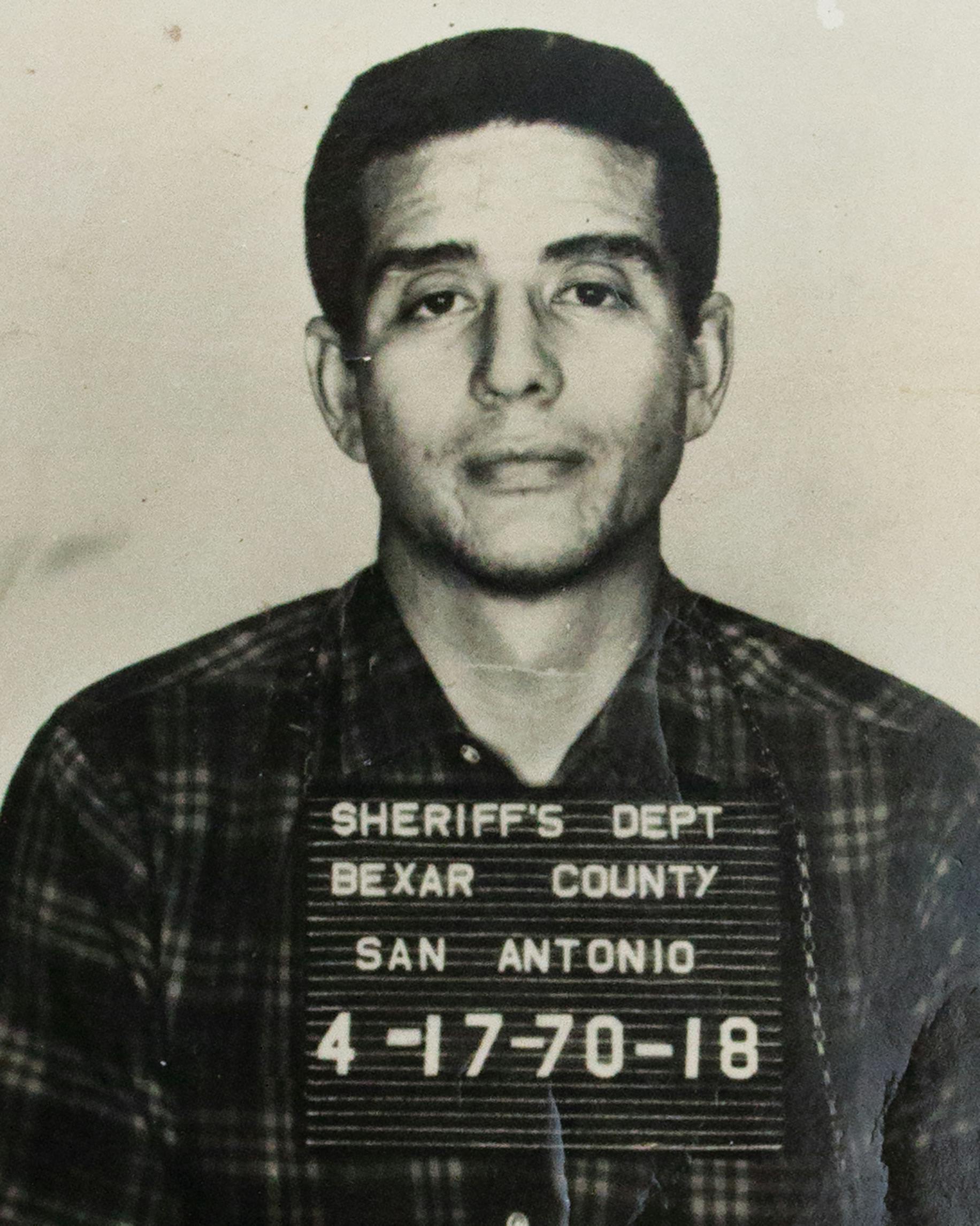

Cruz’s record up to that point confirmed the assessments most prison officials had made when he entered the system in 1961, after an arrest and conviction for the aggravated robbery of an ice house in San Antonio. He’d been described as an eighth-grade dropout and a “hardened incorrigible” with an IQ of 87, one who was an “extremely poor prospect” for rehabilitation.

A clinical psychologist named William Gates, who interviewed Cruz, was the only one who saw something different. To his eyes, Cruz was “intellectually bright” as well as “suspicious, and prone to be hostile to authority.” In a report to the warden, Gates warned that Cruz had “leadership potential,” and that if the prison authorities failed to keep him in line he would “most certainly be a disturbing influence.”

Gates should have been a fortune teller, because it wasn’t just dumb stuff like chasing armadillos or talking back to low-level turnkeys that would get Cruz in trouble. When not working in the fields, Cruz dedicated himself to studying law. Cut off from the siren calls of heroin, marijuana, and alcohol, he’d begun reading textbooks, as well as documents like Supreme Court opinions, the Bill of Rights, and the Constitution. And although he had no illusions of fairness inside the walls of Texas prisons, he came to understand, and long for, the platonic ideal of justice. He almost worshiped it.

Cruz’s early attempts at writing court filings mostly focused on appealing his own case on the grounds of inadequate representation. He had always denied that he’d robbed the ice house and claimed his court-appointed lawyer had been so disengaged that he failed to call an alibi witness. And while lower courts routinely dismissed Cruz’s pleadings, Cruz became known among his fellow inmates as someone who understood the legal system. They called him a “writ writer” and sought him out for help with their own appeals and filings.

Unfortunately, helping other prisoners with legal issues, or keeping legal books or documents in one’s cell, was strictly against the rules. Even talking to another prisoner about the law was a violation and could be punished with weeks of hunger and darkness in the hole. Cruz did several stints in solitary for possessing or sharing contraband books and documents—including Cochran’s Law Lexicon, 4th Edition; Casebook on Criminal Procedures in the Courts of Texas; and The Constitution of the United States of America.

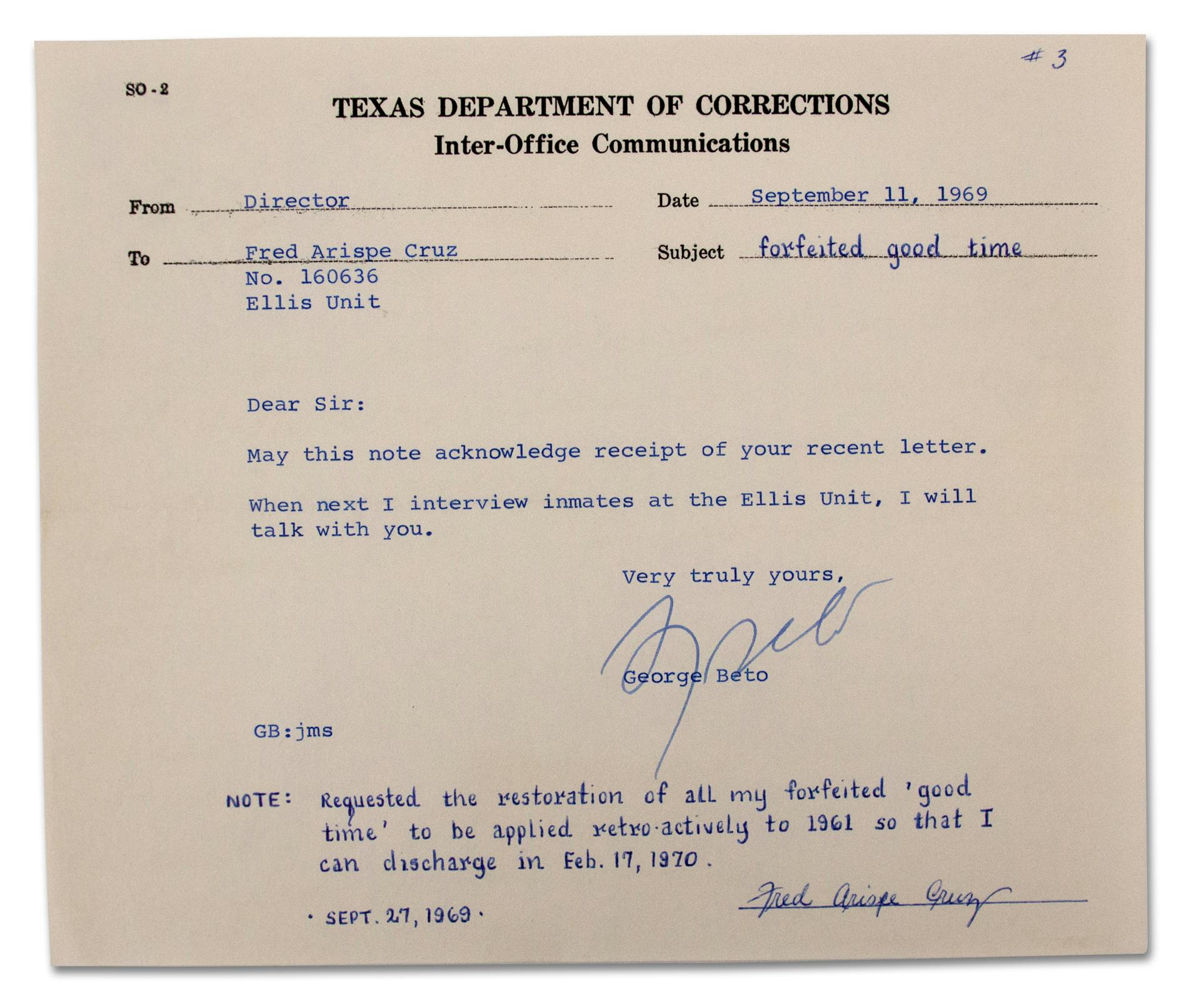

So Cruz lost good time: first weeks, then months, then years. But the punishments wouldn’t stop him. Using his growing legal acumen, he would become the most dangerous man in the cloistered and labyrinthine Texas prison system—a danger not to the other prisoners but to those with real power: the officers and the wardens, and George Beto, the director of the Texas Department of Corrections. As unlikely as it would have seemed as Fred Cruz sat in solitary in the winter of 1967, he would see to it that many of those men’s careers ended in disgrace. The effort would fundamentally alter prison systems across the country.

But he wouldn’t do it alone.

II. PORTIA FOR THE POOR

By all reasonable imaginings, Frances Jalet and Fred Cruz should never have met.

Jalet was born in Boston, and had been among the first cohorts of women to graduate from Columbia Law School, in 1937, but, like many educated women of that era, she found it difficult to put that education to use. She’d gotten married in 1935 and eventually moved to Darien, Connecticut, where the only jobs she could find were teaching and typing. She and her husband had five children, and Frances took charge of raising them. She went to church, she sang in the choir, she volunteered for good causes.

Then, while Jalet’s husband was flying a friend’s private plane on a trip to Chicago, his flight went down; he barely survived the crash. He came home irrevocably changed by the serious head injury he had sustained. He drank heavily and was unpredictable and angry. At one point he became so out of control he had to be hauled off in a straitjacket.

For several years, Jalet tried to keep the marriage going, but by 1954 it was over. Divorced, she moved with her kids to Washington, D.C. for a job with the American Association of University Women. That was one of a series of moves and short-term positions that lasted only a year or two. By the summer of 1959, she had finally found a job that stuck—as a staff attorney on the New York Law Revision Commission in Ithaca, New York. She held that position for eight years, until the last of her children was out of the house.

Jalet longed to be a part of the burgeoning civil rights movements, and saw this moment in time as her opportunity. “I am now without home ties,” she wrote. “My children are grown and need me less. My material needs are small. I want simply to spend all the rest of the time that might be mine giving assistance to those who need it.”

She applied for and was awarded a Reginald Heber Smith Fellowship. It was the first year of the program, which was funded by the federal Office of Economic Opportunity to attract lawyers from top law schools into the field of poverty law. The honor was mostly reserved for attorneys just starting out in their careers, and Jalet’s age made her stand out. After six weeks of intensive training, the fifty “Reggies” were scattered to poverty law centers across the country with the guarantee of a modest stipend from the federal government. Jalet asked where her services were most needed. The answer: Texas.

So, late in the summer of 1967, she packed her car and set out on the long drive to Austin. After a difficult marriage and two decades of motherhood, she was suddenly off on a new adventure. She drove west and south, through the August heat and thunderstorms. She was 56 years old.

A few days after she got to town, the Austin American-Statesman ran a short profile of this peculiar woman who had moved from the East Coast to Texas to help low-income plaintiffs. The writer of the story called her “Portia for the Poor,” after the heroine in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice—a rich heiress who dresses up as a man and fools everyone into believing she is a competent lawyer.

The next week, she received a letter from a prisoner named Fred Cruz. He’d read the article, he said, and wondered if she could help him with his case. Jalet had never set foot in a prison, never handled a criminal complaint—never headed any type of litigation, for that matter. She had yet to pass the Texas Bar. Helping a prisoner was also outside the bounds of her job description at the Legal Aid and Defender Society of Travis County. She was supposed to stick to predicaments in the lives of poor locals: evictions, consumer credit, and unfair debt collection. But Jalet decided she could make the visit on her own time. She called the prison to schedule a visit, and a couple of weeks later, on a breezy and cool late October day, she got into her car and drove the 160 miles to meet Cruz.

The Spark

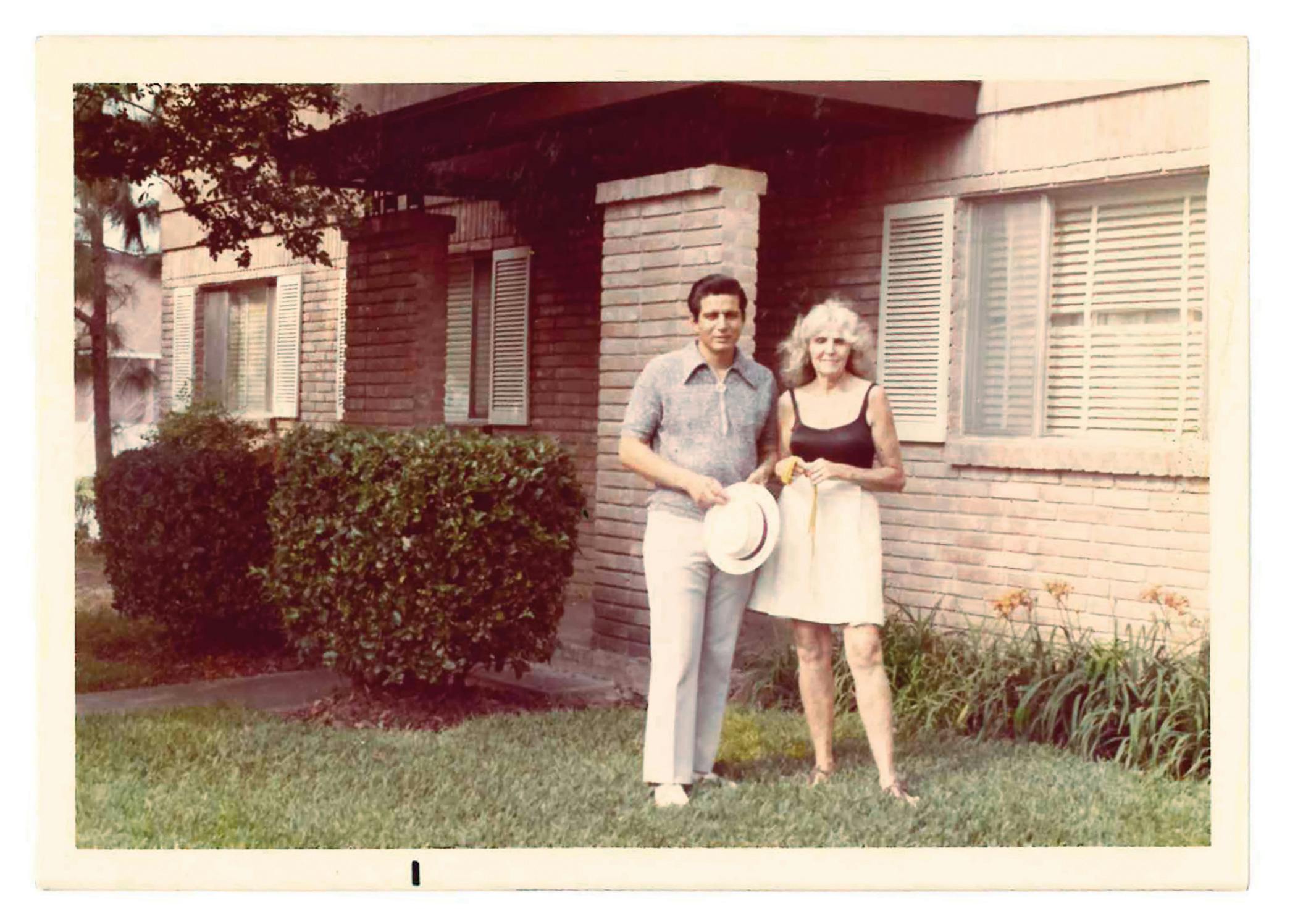

Jalet had no idea what to expect when she entered the Ellis visitors area for the first time. The prison was cleaner and quieter than she had imagined. Cruz was brought in and placed on the other side of a wire mesh partition. He wore a long-sleeved shirt and pants, both made of thick white cotton. She had expected drabber colors, maybe tan or gray. Cruz didn’t fit the mold of a criminal in the movies. His eyes were sad and kind. When he spoke, his voice was soft.

Cruz told her about his desire to appeal his conviction. Jalet told him that she wasn’t a trial attorney and was visiting him on her own time; she could advise him on his case and help him type up his briefs but couldn’t officially represent him. And, due to the length of her fellowship, she only planned to be in Texas until the following June.

Their conversation turned to other issues. They talked about their families and faith. Jalet told Cruz that one of her daughters was also studying Buddhism. As they talked, Jalet learned that Cruz had worked hard educating himself while in jail, reading the Bible, Jean-Paul Sartre’s Existentialism and Human Emotion, Martin Heidegger’s German Existentialism, and contemporary revolutionary tracts like Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. With the little money his mother sent him, he subscribed to the Supreme Court Reports. When he mentioned that one of his favorite books was Milton Konvitz’s Bill of Rights Reader: Leading Constitutional Cases, Jalet told him she knew Konvitz personally. Cruz was awestruck.

Their first conversation lasted about an hour. For Cruz, Jalet’s first visit was a major event. Just to be in the presence of a woman in a knee-length dress was unusual. But what truly amazed him was how she listened. That night, he wrote down everything he could remember about the encounter. He was charmed by her personality and wrote that she seemed “to have a vast resource of understanding and compassion for the plight of man.” As she talked to him, he’d later write her, he felt something that he hadn’t for many years. He’d felt free.

The Bosses

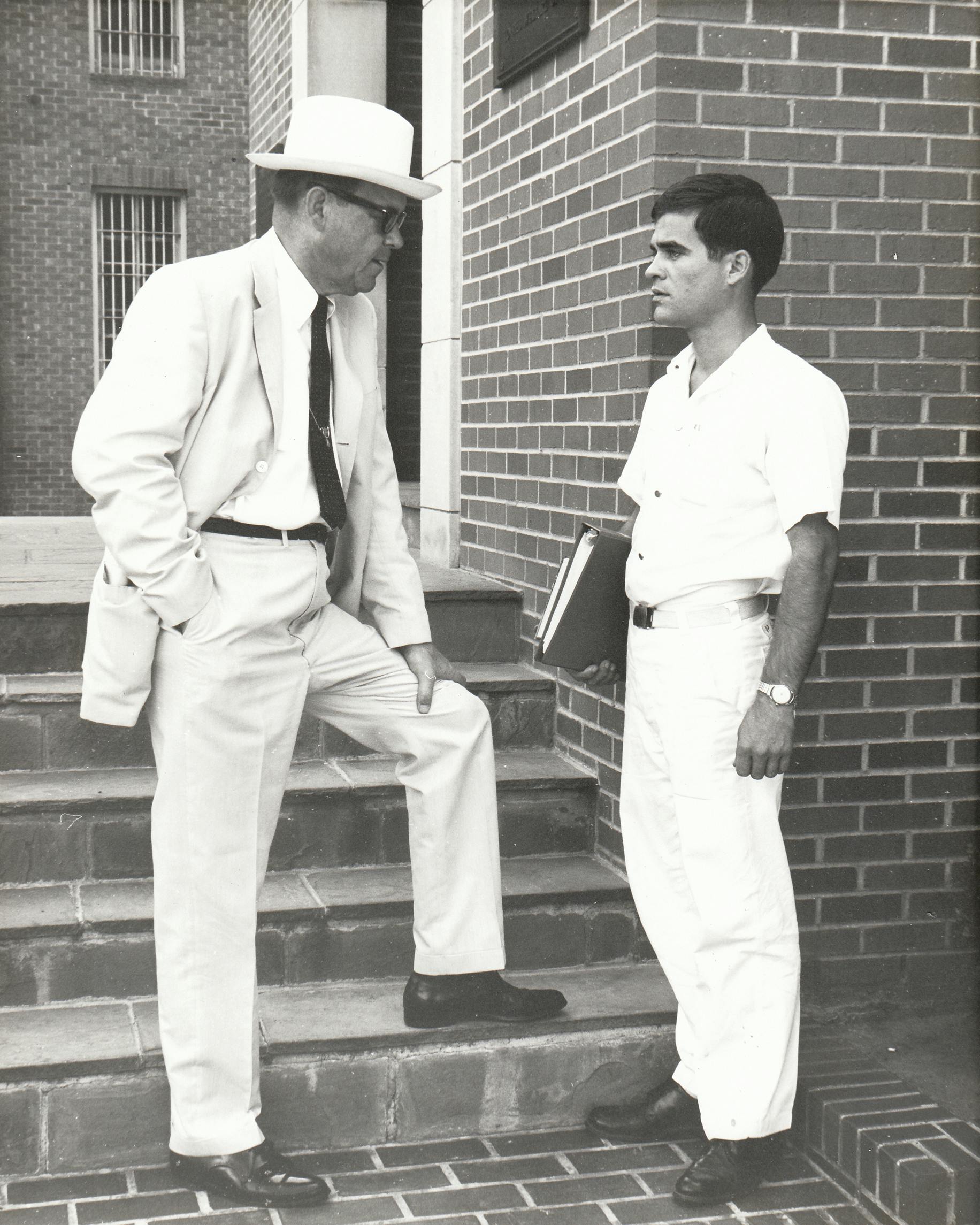

The director of the entire Texas Department of Corrections, George Beto, happened to be visiting Ellis the day Jalet first arrived. In addition to her inmate meeting, she was invited to sit down both with Beto and with Ellis warden Carl Luther “Beartracks” McAdams. Beto had just returned from deer hunting and was in a buoyant mood. Still in his hunting gear, Beto was happy to talk to Jalet about the Texas prison system he oversaw. Barrel-chested and six foot four, he towered over her. The former president of Concordia Lutheran College in Austin and an ordained minister, Beto portrayed himself as an enlightened leader who cared about his charges.

McAdams was another big man. Chinless, with a large gut, the warden had a reputation for brutality. His lumbering girth belied a capacity for sudden ferocity. Prisoners whispered stories of his ability to silently walk up on a man and lay him out with a roundhouse kick to the head. One Houston Chronicle reporter described McAdams as a “big man with a velvet voice, a cherub’s face,” who, “despite the paunch,” could “move like a mongoose when there is trouble brewing.” From later interviews, it seems McAdams disliked Jalet at first sight. He recalled that her skirt was far too provocative for a prison visit and that her mane of graying blond hair was only partially tamed into a bun. “If you dreamed of a witch,” McAdams told a video crew, “that’s exactly what she looked like.”

But Beto put on a charm offensive, the one that usually won over reporters and other visitors to his domain. He was always on the lookout for “do-gooders,” and usually managed to show interlopers only what he wanted them to see. The press reliably sang Beto’s praises in glowing feature stories, and there were things to praise: Beto had overseen the construction of new, more modern facilities and opened vocational learning and educational programs. Convicts could now earn their GEDs while in prison.

In their first meeting, Beto felt obliged to warn Jalet of how inmates often sought to con outsiders. He told her she should be particularly wary of Fred Cruz. Cruz was often in trouble for being a “writ-writer” and helping other prisoners out with their legal cases. Beto saw him as crafty, always trying to “out-snicker” him. He didn’t want Jalet to be taken advantage of by such a “nonconformist.”

“Is being a nonconformist a bad thing?” asked Jalet, who was, of course, something of a nonconformist herself.

One Houston Chronicle reporter described Warden McAdams as a “big man with a velvet voice, a cherub’s face,” who, “despite the paunch,” could “move like a mongoose when there is trouble brewing.”

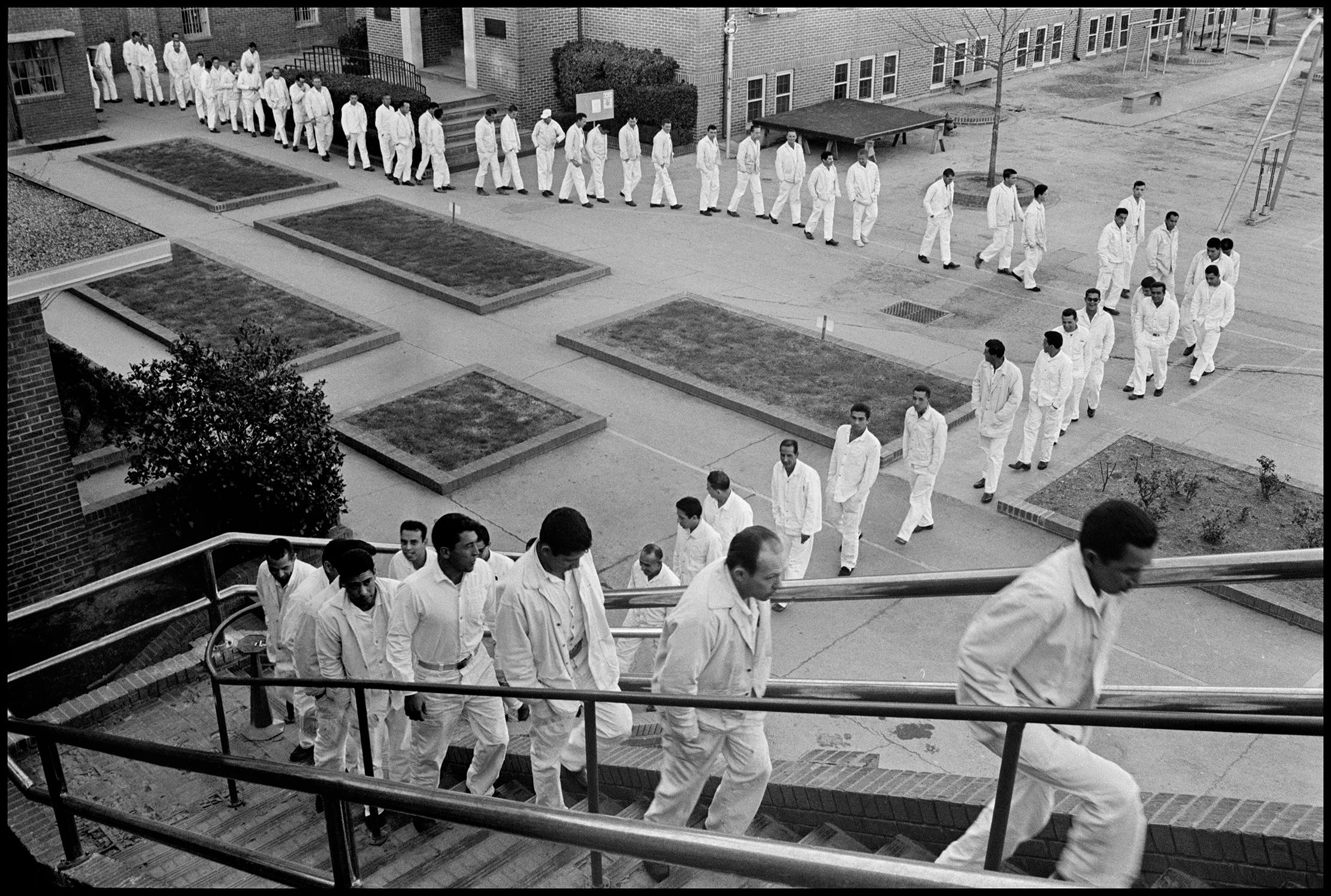

Beto probably didn’t like the sound of her comment. But he would have had no reason to be concerned about the arrival of a middle-aged female lawyer. He was one of the most powerful men in the state, controlling an empire of 14 separate penal facilities, which held more than 12,000 men and women. His prisons were spread across nearly 100,000 acres of alluvial bottomlands formed by the Brazos and Trinity Rivers, from Anderson County down to the Gulf of Mexico. Due to the size of the land holdings and number of employees and ancillary businesses supported by the TDC, locals called the area “the prison crescent.”

Beto liked to fly from one unit to the next in his private plane, often showing up unannounced early in the morning. He was known as “Walking George,” for his penchant for strolling among inmates during visits. Behind his back, inmates gave him another nickname: “Promising George,” as their requests and complaints never seemed to go anywhere despite his assurances.

“He was an educated man of God, a wonderful guy,” said A.R. “Babe” Schwartz, who served in the legislature. “We tried to get him as much money as we could.”

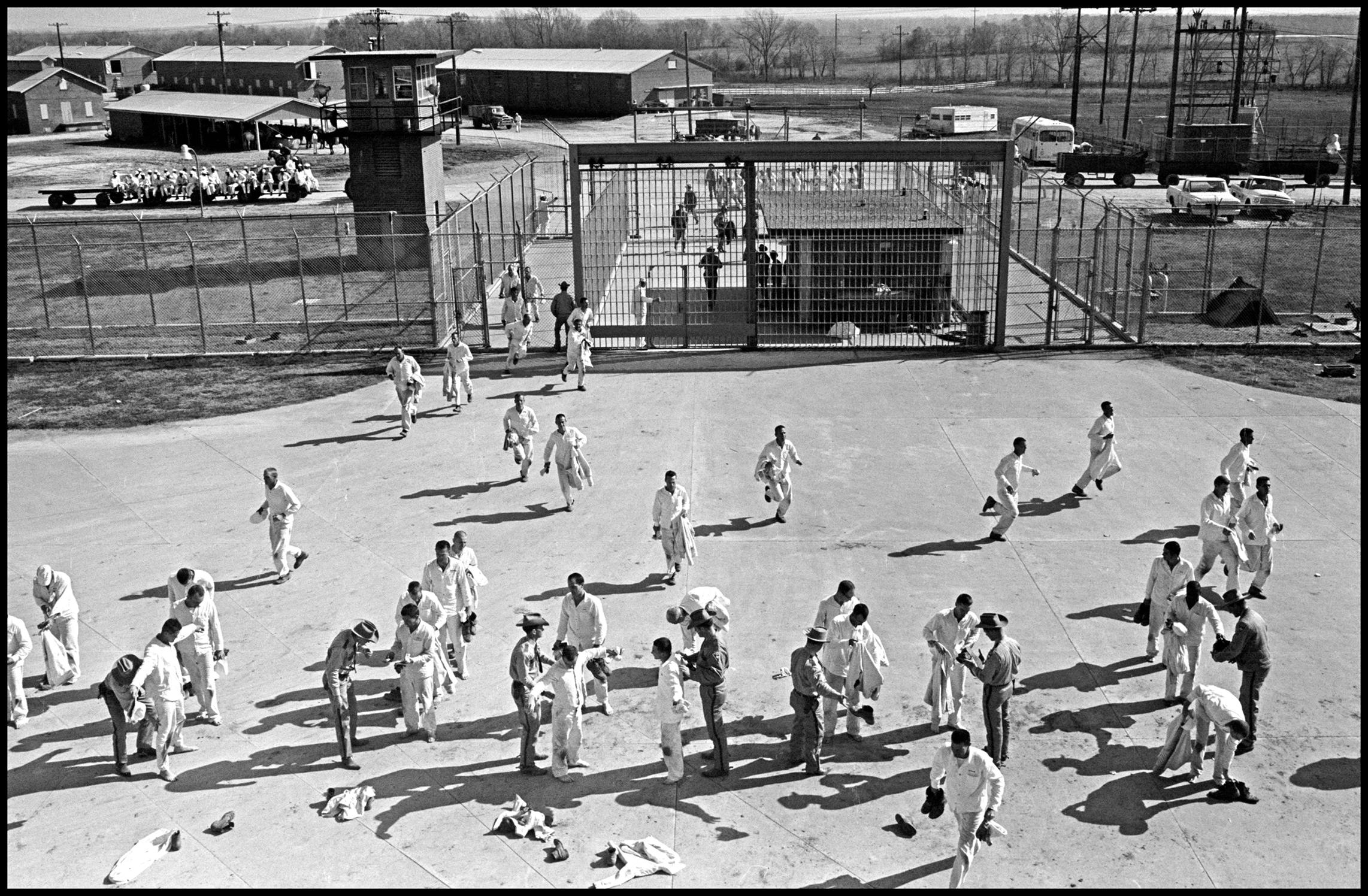

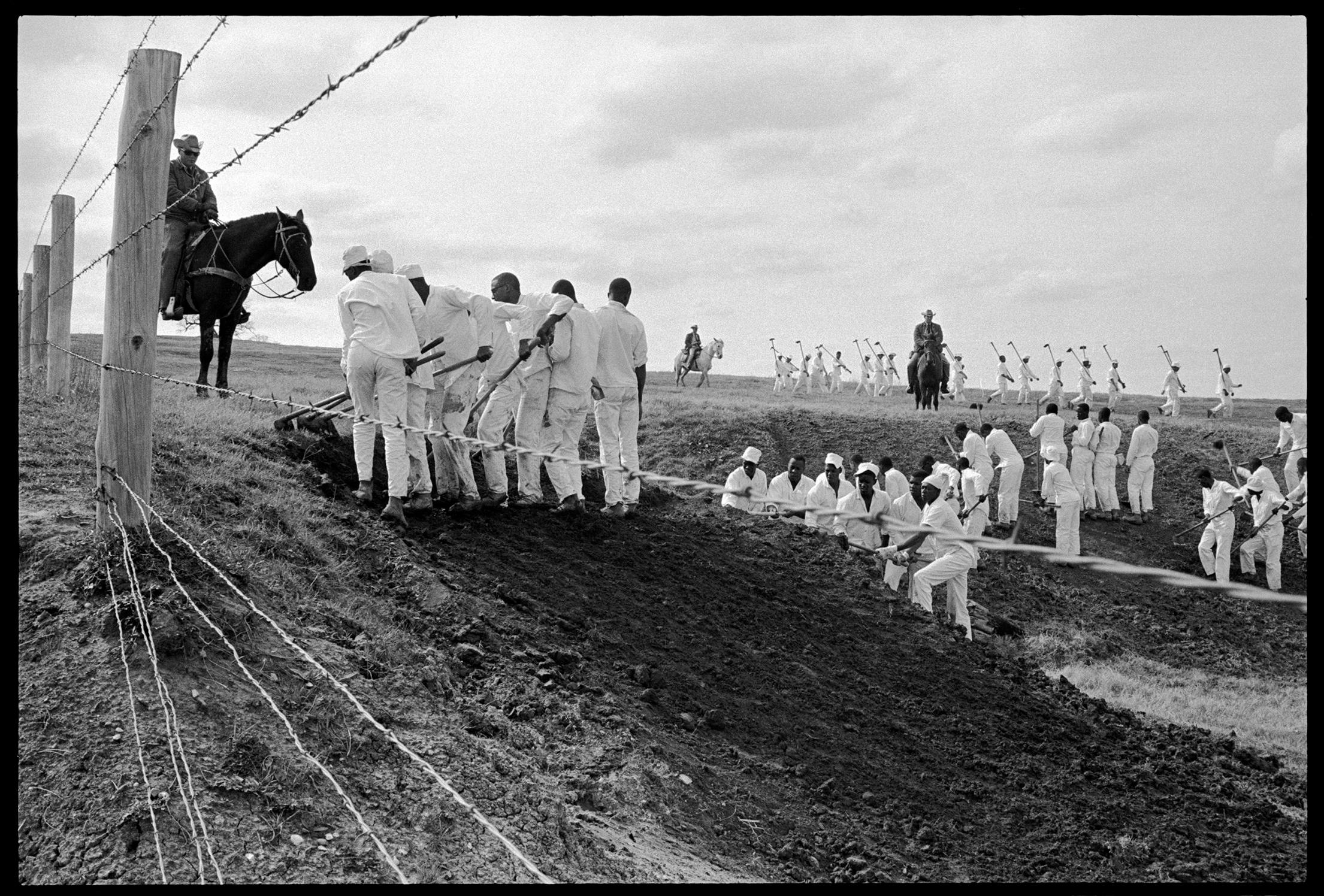

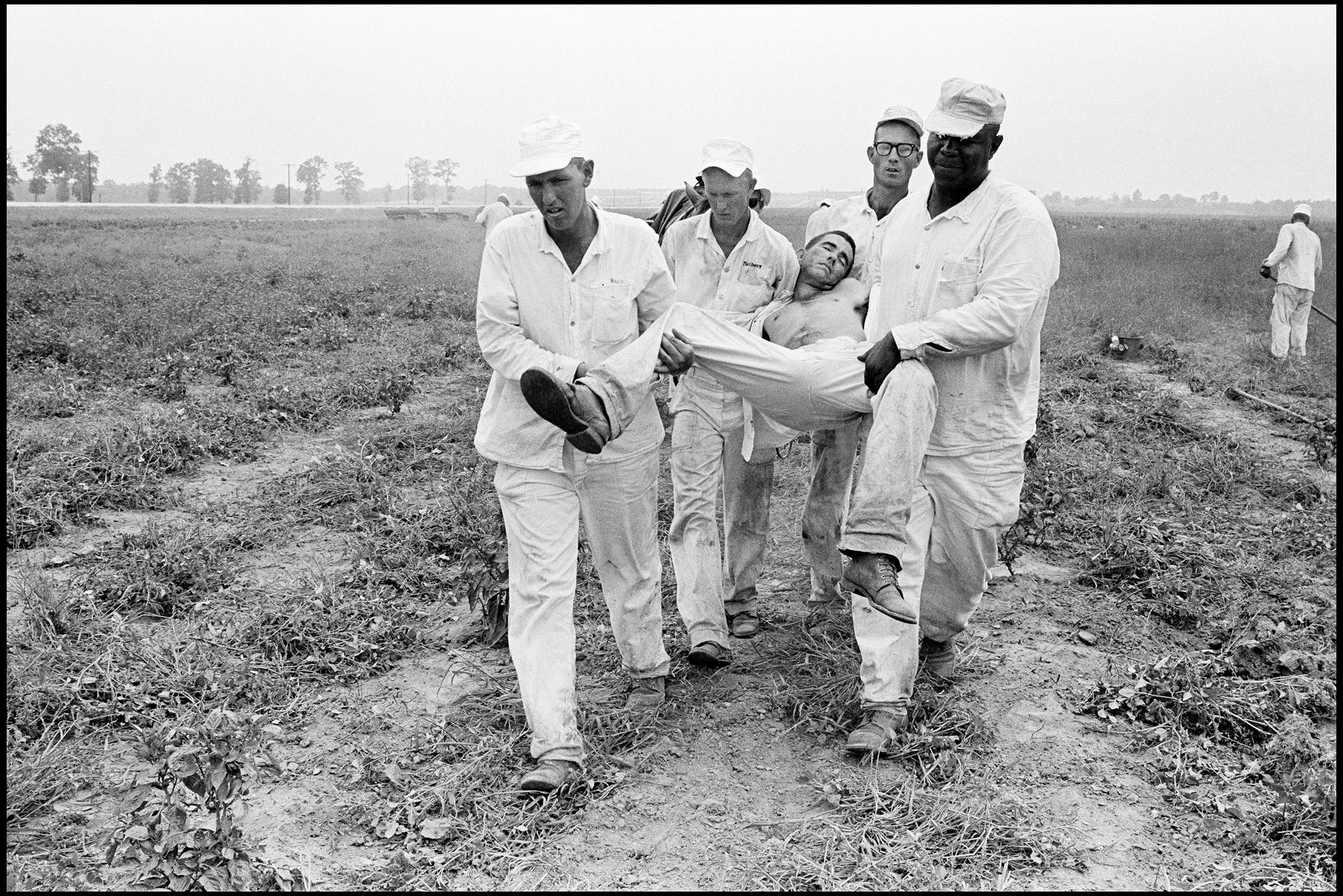

But it was the fact that the prison system didn’t need much money that made Beto popular. Much of the land controlled by the TDC was rich farmland, producing cotton, sugar cane, corn, and feed crops. The system had more than 15,000 beef and dairy cattle, 17,000 hogs, and 112,000 chickens that produced more than 800,000 dozen eggs a year. Convicts not only grew cotton—more than 3,500 five-hundred-pound bales a year—but also processed it through gins and spun it into cloth, which was sent to the Goree Unit in Huntsville, where female inmates sewed it into linens and the white uniforms the prisoners wore. Prisoners were also put to work building the stone walls and fences that confined them. Beto ruled a veritable self-contained empire.

So there was little chance that this lone lawyer—particularly one who barely knew a soul in Texas—could challenge Beto’s authority. The Constitution itself codified his right to treat his prisoners as slaves: the 13th Amendment, adopted in 1865, had abolished slavery in the United States “except as a punishment for crime.” From that point to well after World War II, Texas had simply swapped out slaves for inmates and kept on picking cotton. In the mid-1960s, the federal courts in other states began to hear prisoner’s rights cases, but little had changed in Texas, where federal judges still held to what was called the “hands-off” doctrine.

In the end, Beto no doubt knew that if his charm didn’t win over Jalet—if she became a problem to deal with—he had plenty of other cards he could play. All the prisoners’ mail, both incoming and outgoing, was read and censored, so he could find out what Jalet and Cruz were up to or just cut off their communication. He could have McAdams throw Cruz in solitary. And he had plenty of political pull in Austin: it wouldn’t take more than a couple of phone calls to make Texas a very inhospitable place for Frances Jalet.

III. THE PARTNERSHIP

Jalet’s first meeting with Cruz left an impression on her, too. Writing about the experience in a letter, she described Cruz as “an intelligent young man who has had a hard time.” For a poorly educated convict, he had an amazing grasp of legal issues. “I find he has courage also,” wrote Jalet. And in her private notes, there was a hint of something else. “Fred Cruz is handsome,” she wrote. “He can think. He can persuade. He can write. … It didn’t take much to arouse my interest in joining in with him.”

Jalet and Cruz began corresponding several times a week. They were both prolific writers, Jalet clocking 110 words per minute on an old manual typewriter that printed in cursive script. Because of the censors, letters often arrived weeks late and sometimes in batches. Cruz and Jalet took to numbering their correspondence so they would know when letters went missing.

On December 11, 1967, the day before Cruz’s 28th birthday, he was back in solitary. A corrections officer with the Dickensian name of Major Savage had accused him of disobeying an order not to share his Buddhist religious materials with other inmates. When Cruz was let out, he wrote in his diary, McAdams came to personally warn him that if he kept writing people about matters that didn’t pertain to his case, he would be put in solitary indefinitely. The warden and Savage accused him of “agitating” the other prisoners. Cruz couldn’t quite figure out what they were upset about, but it seemed to have something to do with his new correspondent. McAdams told Cruz he was thinking about cutting off all visits from that woman lawyer.

But over the first few months of 1968, Jalet and Cruz started to write each other almost daily, and she drove to visit him as often as she could. They discussed procedural issues, constitutional matters, and the moral underpinnings of justice. Jalet brought Cruz law articles, including one she had published in the UCLA Law Review titled “The Quest for the General Principles of Law Recognized by Civilized Nations.” Cruz would sometimes write to Jalet throughout the night; one letter penned shortly after one of her visits went on for twelve handwritten pages.

After a particularly noteworthy meeting, where for the first time they’d been allowed to be in the same room rather than separated by a barrier, Cruz wrote, “It was good to see you again, Mrs. Jalet. It took us a long time, but we finally got to shake hands didn’t we? During your visits … I often experienced the same frustrations Moses must have felt on the Mountain in being so close to godliness and not being able to make physical contact with it … You seem to have a very rare gifted capacity to employ your charm in such a tender fashion that while speaking with you a person feels very much at ease and comfortable in expressing one’s views.”

He wanted her to know the good and bad of the man he was. Over the course of their first year of contact, Cruz told Jalet that by the eighth grade he had stopped attending school, sunk into the local drug economy, and gone from smoking marijuana to shooting heroin. He had been in and out of the juvenile justice system and arrested multiple times. He also told her of an incident that scarred him deeply: at 17, he was goofing around with an uncle’s pistol, showing his best friend how fast he could draw it from his waistband. The gun fired and his friend fell, mortally wounded. No charges were filed; it was just another tragic accident in the bad part of town.

“I have been reared and grown up in [a] community of criminals who are anti-social to the greatest extent,” he wrote. “My place has always been among the worst. … I’m telling you these things in the hope that by learning some of my past background you will have a better insight into the nature of my existence. I do not have anything to hide, nor do I have anything of which to boast.”

Jalet would later insist that while Cruz was in jail their relationship was strictly one of client and lawyer. Their deep intellectual kinship, however, was apparent from the start.

The Mask of Respectability

Jalet became increasingly incensed by what she was learning from Cruz about his treatment in prison. His punishment for practicing and sharing his Buddhist faith, for one, seemed a clear violation of his constitutional rights. What was more fundamental than the freedom of religion? The brutality of solitary, and the arbitrary way it was used to punish prisoners for sharing legal advice, also seemed unconstitutional.

Prisoners elsewhere had begun to petition federal courts for constitutional protections; a few years before, a black Muslim prisoner in Illinois had won a Supreme Court case after being denied permission to buy religious materials or meet with ministers of his faith. But at Ellis, Cruz and others continued to be punished—including with solitary—for sharing their religious beliefs.

Cruz told some other prisoners about Jalet’s assistance and interests, and soon she was meeting with two other inmates at Ellis.

She met with a Muslim African-American prisoner named Bobby Brown, who had been punished with months of solitary confinement for practicing his faith. A white prisoner named Ronald Novak, serving a twelve-year stint for robbery and assault, also requested Jalet’s help. Novak struggled with mental illness and hallucinations. He told Jalet of being repeatedly beaten and starved in solitary, which had exacerbated a kidney ailment that dogged him. Novak was a troubled man and no model prisoner. Three years before meeting Jalet, he had disarmed two guards, stolen a truck, and made his way to Houston before being caught and thrown into solitary.

Based on her interviews, Jalet began to compose a document she called “The Ellis Report.” From the very first sentences of its fifteen typed pages, it was an all-out indictment: “The prisoners confined in the [Texas Department of Corrections], most especially on the Ellis Unit … are deprived of their constitutional rights and subjected to a pattern of repression, harassment, and even torture that is shocking. Through abusive practices based on brutality and dehumanization, the ‘inmates’ live in constant fear.”

Warden McAdams played a central role in the report. In Cruz’s diaries, he described McAdams as showing an “unwavering belief in the efficiency of brute force,” and said the warden’s intent was nothing less than “to inflict as much mental anguish as possible, lower morale, and plunge men into darkest despair.”

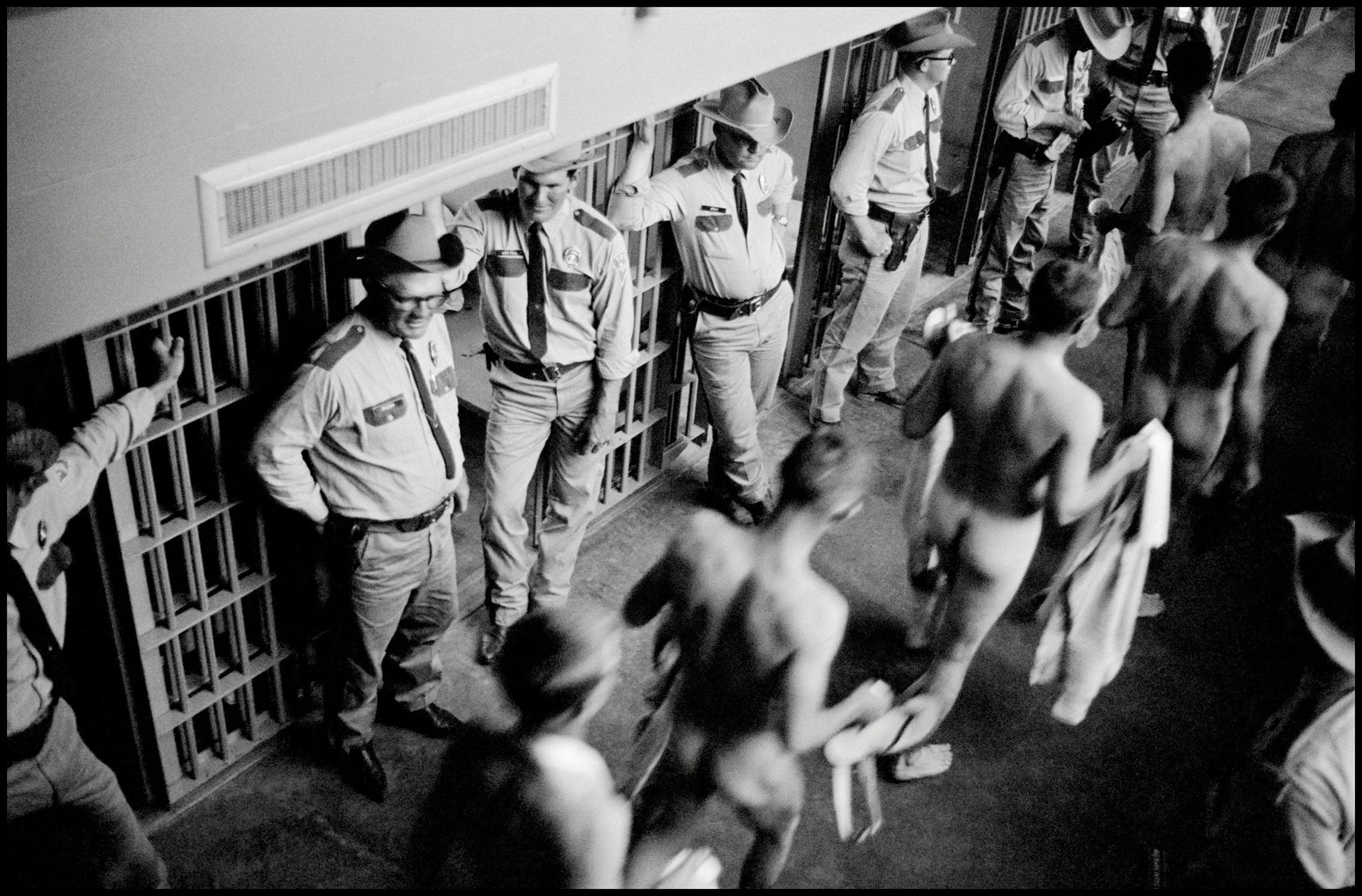

Jalet documented the stories she had heard from prisoners of being made to stand on a rail, of being hung from bars in straitjackets. She wrote of routine beatings with fists, baseball bats, brass knuckles, and blackjacks. McAdams himself often led the action, she wrote, particularly if an African-American work squad showed signs of malingering or “bucking.” She told of one incident when a prisoner was made to shell peanuts for five days straight until his fingers were so raw that he attempted suicide by slashing his own wrists.

She also exposed the role of the “building tenders,” inmates who were allowed to keep weapons so long as they were willing to tune up troublemakers at the request of prison administrators. They had remarkable power. “Building tenders are henchmen of the establishment and have authority to harass, intimidate and even to beat—possibly kill—prisoners,” Jalet wrote in her report.

The use of building tenders was being phased out across America, but Texas was a holdout. This was one of Beto’s dirty secrets: he could run his prisons cheaply not just because he had free labor, but because select prisoners acted as his guards and enforcers. They didn’t cost a thing; one just needed to give them some weapons and a few extra privileges.

Jalet began to circulate copies of the Ellis Report to state agencies and civil rights groups. She sent one copy to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, where it found its way to a young Harvard-trained staff attorney named William Bennett Turner. Jalet became increasingly convinced that the abuses in the prison—particularly the use of solitary confinement and the restriction on prisoners helping each other with legal pleadings—needed to be challenged in court.

It couldn’t have taken long before Beto caught wind of the report. If he had any doubt about whom Jalet was likely to sue, the first section cleared that up. The department’s “mask of respectability,” she wrote, “is furthered by the status of Dr. George J. Beto, a former Lutheran Minister and College President, who, though he cannot be blind to what goes on, manages to obscure the truth from interested eyes.”

The implications would have been obvious to Beto and his wardens: Jalet, using Cruz as her key informant, was declaring war on the Texas prison system.

The First Firing

In the spring of 1968, Beto decided it was time to go on the offensive. His first countermove was to lodge a complaint with Jalet’s boss at the legal aid office in Austin. What right, he wanted to know, did this out-of-state lawyer have stirring up the prison population? Jalet’s boss immediately took all her cases away. She wrote to her home office back in Philadelphia, which managed to find her a new posting at a poverty law center in Dallas.

Jalet was in her new job for only half a year when Beto phoned her new boss, Joshua Taylor, to say that his latest hire was a thorn in his side. Taylor dutifully instructed Jalet to stop visiting the prisons. Jalet refused. The bitter fights between the two—sometimes aggravated by Taylor’s late-afternoon drinking—became the talk of the workplace. “If you don’t like the way I run this office,” he shouted at her at one point, “you know where the door is!”

In a memo, Taylor ordered Jalet to no longer assist prisoners and to stop “attacking the policies” of the Texas prison system. When Beto got a copy of Taylor’s directive, he had a pretext to bar her from his prisons. He told his wardens to remove Jalet from approved visiting and correspondence lists. Suddenly, Jalet was completely cut off from her clients.

In response, Jalet filed an injunction and a restraining order against both Beto and Taylor. Filing a motion against her own boss, she surely knew, would be the last straw—and on Christmas Eve, Taylor called her into his office and told her he was firing her for “insubordination.”

That Christmas of 1968 was a tough one. On top of being let go and not knowing how she was going to pay rent, Jalet came down with the flu. It was also her first Christmas away from her children, and her youngest, Frances, a college student in New York, sent her a concerned note. “Are you staying down in Texas for Mr. Cruz and the others?” she asked. “If so I think that’s not reason enough. There are minority groups up here too and, more important, there are your children up here who need you.”

The head of the fellowship program in Philadelphia offered to find Jalet another poverty law center to work at back east. Although she longed to be near her children, Jalet refused. “I can’t just walk off [from] my commitments to prisoners here,” she wrote to a friend. She knew too much about what was happening behind the walls. Prisoners’ constitutional rights weren’t theoretical—they could be the difference between living and dying. She also didn’t like the idea of giving in to bullies.

So Jalet had to find another organization in Texas willing to take her in. By February, she had accepted the post of managing attorney of the Legal Aid Clinic at Texas Southern University Law School in Houston. Jalet found it to be small and poorly funded, but Houston had one advantage: it was only eighty miles from the Ellis Unit. She would have time to keep up with her prison cases—if she could get Beto’s ban rescinded.

Jalet learned that officials were moving her three clients between solitary and segregated isolation and pressuring at least one of them to sign papers accusing her of inciting violence.

Weeks went by with no ability to correspond with or visit her clients, and Jalet worried for Cruz, Novak, and Brown. Would they think she had abandoned them? Fortunately, she had the prison grapevine. She learned that officials were moving her three clients between solitary and segregated isolation and pressuring at least one of them to sign papers accusing her of inciting violence. She also learned that Beto and McAdams were keeping track of her. McAdams had bragged to one prison visitor that he knew exactly when Jalet had arrived in Houston and the dates of her trips to and from Dallas. She began to worry that her phone had been tapped and sometimes imposed on her neighbors when she needed to make sensitive calls.

“It is all like a nightmare,” Jalet wrote. “Especially when I think that the three prisoners I’ve tried to help have such a hard time.”

Jalet also began to reach out to powerful lawyers in Texas. Jalet hadn’t been well received by the state’s legal community, but when her fellow lawyers learned that a state official had barred her from speaking with her own clients, they began to come to her aid. One well-connected attorney in Houston was so disturbed by Jalet’s reports that he called the state’s attorney general’s first assistant, and convinced him to intercede.

By the time the Texas attorney general’s office negotiated a cease-fire—Jalet would be allowed to visit her clients if she dropped her legal action against Beto—things had gotten desperate. Bobby Brown had for months been held in a strip cell with no sheets, pillow, or toiletries. Novak had been beaten savagely by two building tenders, and the weeks he had spent in solitary had further damaged his precarious mental health. As for Cruz, after multiple stints in solitary, he could barely put together a coherent sentence. His voice was weak from disuse; he hadn’t spoken more than a few words in months.

But Jalet’s battle with Beto was a hot topic among the prison population. Beto was not someone who backed down, and yet the diminutive Yankee woman was back. Suddenly, dozens of inmates and their families asked for her assistance.

IV. THE FIRST TRIAL

On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon. The correspondence between Jalet and Cruz makes no mention of the event—they were far too busy pushing their first major lawsuit through the court system. Jalet helped Cruz and Novak write and file a lawsuit challenging both the TDC’s rule barring prisoners from helping each other with legal matters and the use of solitary confinement as punishment for prisoners sharing legal advice. They were finally going to challenge Beto and the prison system in federal district court.

Jalet wasn’t a seasoned trial attorney—in fact had no trial experience—so she partnered with William Bennett Turner, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund lawyer who had become interested in her prison advocacy after reading the Ellis Report. He flew out from San Francisco to help her interview witnesses and prepare for trial. His work ethic was a match for Jalet’s, and the pair toiled seven days a week. They did take a break and pay the one-dollar admission to witness the annual Prison Rodeo. Prisoners in striped outfits roped calves and rode bulls and broncos; others dressed as rodeo clowns. It was the first rodeo either of the two had attended.

A month before the trial date Jalet was at Ellis meeting with her clients. At noon, she left the prison to drive to Huntsville for lunch. She noticed right away that the steering in her car felt different. Rounding a curve, she lost control and crashed into a ditch. Although she was badly bruised, the x-rays showed no broken bones, and soon after her night in the hospital she was back at Ellis to continue her meetings.

She wondered later whether someone had tampered with her car, and regretted not having it inspected before it was repaired. “You are in redneck country,” Novak wrote her. “How do you know the incident was an accident?”

On December 15, the case came to trial in Houston. The judge assigned, Woodrow Seals, was a World War II Air Force veteran and a Democrat who had been a campaign manager for John F. Kennedy. He’d been appointed in 1966 by Lyndon B. Johnson, and though he didn’t have a long track record, given the possibility of other, good-old-boy judges in Texas courts, it seemed like a lucky break to get him.

Cruz wore a suit and sat next to Jalet at the counsel table. At the judge’s request, guards were placed throughout the courtroom to assist the U.S. Marshals. Several reporters, tipped off to a good story by letters Jalet had sent to their editors, sat with notebooks at the ready.

The trial began and Jalet and Turner called their first witness: Novak. He described the brutality and mental anguish of solitary. He told the judge that over a three-month period in the previous year he had spent more than 78 days in solitary in four separate stints. The starvation and isolation in darkness had pushed him beyond his mental limits. In despair, he said, he managed to saw through one of his Achilles tendons—a common act of self-mutilation that prisoners called “heel stringing”—in order to avoid future work in the field and be moved to the hospital unit. The reason he had been punished so harshly, Novak testified, was that he had asked Cruz for help in filing legal papers. The penalties became even more severe when he began to meet with Jalet.

Under cross-examination, he admitted that there were times in the past when he’d been placed in solitary for more serious offenses, including the time he had escaped in a stolen truck.

“What are they supposed to do with you [instead], give you a medal?” Judge Seals asked, in the first of many hints that Seals’s assignment might not have been such good fortune after all.

A Moral Duty to Resist

When Cruz took the stand, Judge Seals took over the questioning. If prison officials couldn’t use solitary, the judge wanted to know, what punishment would be the most effective in reprimanding a prisoner who repeatedly violated prison regulations?

“How about whipping?” Seals asked. “Would that deter people from violating the regulations in prison if you tied them to a stake in the prison yard and whipped them, not break any bones, not whip them unconscious, but whip them so that they know they’ve had a whipping?”

The judge seemed to want Cruz to admit that, on the scale of all possible penalties, solitary wasn’t the worst. Cruz, who had spent hundreds of hours thinking and writing about the nature of such punishments, gathered his thoughts.

“When you use physical force on a man,” Cruz said, “the only thing you do is breed hostility. … If you breach his respect for authority and he goes back in society, he takes that hostility and hatred with him, and that’s why a lot of people go back in society and commit more crimes and it creates a cycle.”

Judge Seals considered this answer unsatisfactory.

“Suppose, though, you have a prisoner who is not very smart and he might be a little emotionally disturbed,” the judge said, in a likely reference to Novak. “Now, don’t you think that he should be punished so he will learn that he can’t keep doing what he is doing?”

“I believe those people should be helped through a psychiatrist and counseling so that they would be able to understand,” Cruz said. “If they are not responsible for their actions, I don’t believe that they should be punished.”

“Is there any situation,” Seals asked, “where punishment does help a prisoner when he violates a regulation?”

Cruz admitted that sometimes a prisoner would have to be isolated if he were violent, but suggested that education and mediation would be better than solitary, in the long term, to help prisoners follow the rules and understand right from wrong.

“Suppose you give him another chance,” Seals pressed, “and he violates a valid regulation again? What would you do with him then?”

“I guess just repeat the process,” Cruz said.

“Suppose it doesn’t help?” the judge asked. “Here is a warden with hundreds and hundreds of people. … Don’t you think if he didn’t have some way of punishing these people, that he couldn’t run the prison? … How can he enforce discipline?”

“I don’t have the expertise on that, your honor,” Cruz said. “I can just say from my own experience and the effect this punishment has had on me.”

“What has that done to you?” Seals asked.

“For one thing,” Cruz began, “it has made me more resolute in trying to enjoin some of these unreasonable regulations that I feel are wrong.”

Seals wasn’t having any of this.

“The law did not give you the power to make the regulations, see?” Seals said. “You are just an uneducated young man with an eighth-grade education. The law puts power to regulate the prison in experts’ hands like Dr. Beto. Why don’t you recognize that that’s what the people of Texas want to do and obey its regulations, even though you disagree with them?”

If Seals thought he could browbeat Cruz into submission, he was wrong.

“I recognize the fact that he does have a broad discretion in promulgating these rules and regulations,” Cruz responded. “But I also recognize the fact that he could not enforce a rule and regulation that is in contradiction of federal law. He is under the obligation of law, just like I am … He also has to obey the law and he also has to protect my rights in support of regulations that [punish] me for exercising constitutional rights.” Because Beto had not provided that protection, Cruz said, “I feel I have a moral duty to resist it and that’s what I have been doing.”

Jalet already had great admiration for Cruz’s mind, but his performance on the stand took her by surprise. He had looked different, dapper in his suit and tie. And his preternatural poise facing rapid-fire questions from a district court judge amazed her. She had no doubt that, were he given the opportunity, he could be a great attorney.

George Beto took the stand at the very end of the weeklong trial. To Jalet’s eyes, he was clearly uncomfortable under oath. His answers were imperious mini-lectures about the difficulties of his job and the state of incarceration in America. As he had done throughout the week, Judge Seals took over much of the questioning.

Immediately after the close of the trial, just five days before Christmas, the president of Texas Southern University told the president of the law school that he’d have to fire Jalet or the university would lose funding.

“Is there any particular reason why you do not want Fred Cruz assisting other prisoners in the preparation of writs?” Seals asked Beto.

“He could develop an unconscionable control over other inmates by setting himself up as a lawyer,” Beto told the courtroom. “There are two types of prisons, those the convicts run and those the administration run. … I live in mortal fear of a convict-run prison.” Of course, what Beto really meant was that he didn’t want his prison run by convicts who were not in his control; cell blocks across Texas were already run by the building tenders.

Immediately after the close of the trial, just five days before Christmas, the president of Texas Southern University told the president of the law school that he’d have to fire Jalet or the university would lose funding. The faculty and the students at the school protested, but to no avail. “I’m deeply discouraged,” Jalet wrote in a letter. “[I] seem of late to be batting my head against a stone wall. Dr. Beto has almost succeeded in running me out of the state.”

It was little surprise that she felt that way—Jalet was taking on a man with incredible power and influence not just in Texas, but across the country. As 1970 began, Beto’s public reputation was at its peak. He was in his second year as the president of the American Correctional Association and he soon would be awarded the distinguished alumnus award by the University of Texas. He gave frequent speeches across the United States and internationally and was becoming known as “the grand old man of the cold gray walls.”

Relying on the Good Faith of Dr. Beto

After the trial Cruz was temporarily sent to the Wynne Unit, where he was placed in isolation and denied all privileges. Cruz was undeterred. While he didn’t yet know the outcome of the trial, he had challenged Beto and the prison system in front of a federal judge.

In the spring of 1970, Cruz managed to secure a pen and, using his ration of toilet paper, wrote a class action lawsuit against the State of Texas, stating that the prison system had punished him for trying to exercise his religious beliefs. He managed to get the toilet paper out of prison and filed in a district court. Whatever the outcome of the first case, Cruz and Jalet now had another lawsuit in the works.

In October, Judge Seals’s ruling came down: Cruz and Novak had lost. Seals ruled that prisoners had no need to help each other in legal matters because the year before the Department of Corrections had hired an attorney to provide assistance—one attorney for 14,000 inmates. Seals parroted Beto’s testimony that writ writers like Cruz might use their legal knowledge to control other prisoners—even though there had been no evidence that this had occurred.

As for solitary being a cruel and unusual punishment for prisoners helping each other out with legal matters, Seals decided that prison officials should have great leeway in choosing disciplinary measures, “lest the judicial stranglehold sabotage the entire system.” This reaffirmed the “hands-off doctrine” that gave administrators like Beto such enormous power over the lives of the inmates.

“Rather than define arbitrary requirements,” Seals wrote, “… we rely on the good faith of Dr. Beto and other prison officials to effect the spirit of the Constitution. … It is clear to the court from the evidence that the Texas Department of Corrections is an outstanding institution in every respect. The court is further convinced that Dr. George J. Beto, Director, is a fair, kind, and just man and an excellent administrator.”

About two months later, the class-action freedom of religion suit that Cruz had written on toilet paper was dismissed without a hearing at the district court in Houston. The judge cited Seals’s logic in the Novak case: a Buddhist inmate counseling other inmates or sharing religious literature might “influence” and “control” them, leading to a “convict-run” prison. The constitutionally guaranteed right to freedom of religion was, the judge wrote, best “left to the sound discretion of prison administrators.”

Jalet got to work appealing both losses, but they were devastating blows to her clients. Novak, his body long racked with chronic health problems, just seemed to give up. He couldn’t speak coherently, his pulse was rapid and irregular, and he was breaking out into a rash. Alvin Slaton, another of Jalet’s clients, who had trained as a nurse prior to prison, took on the charge of his care. When Novak started spitting up bright-red blood, Slaton begged guards to get him sent to the hospital. He was told that a doctor would be around soon for his routine visit. By December 14, Novak was in agony. He couldn’t defecate or keep food down. Slaton asked if he could at least administer some demerol to ease Novak’s pain. The guards refused.

A few days later Dr. Sheldon, the prison psychiatrist, came by on his rounds. He was appalled by Novak’s condition. He immediately got on the phone, yelling: “I’m not bullshitting. Get an ambulance out here right now. … [This man] is dying.”

On Christmas Eve, Jalet wrote to her troubled client, worrying about his declining health and telling him she would visit him soon. Novak would never read the letter. He died the day after Christmas.

V. THE LONG GAME

As 1971 began, Cruz and Jalet had little to show for their three-year partnership. Seals’s decision was a spectacular loss. Cruz’s toilet-paper appeal for religious freedom seemed to be going nowhere. Beto’s power and reputation had, if anything, grown.

Jalet knew that setbacks and slow progress were to be expected in civil rights work; battles for the rights of marginalized communities were rarely won at the lower court level. She was playing the long game. She knew that each time she managed to get a representative from the Department of Corrections to answer questions in a deposition or on the stand, she was creating a record of their lies and obfuscations. That testimony, she hoped, would eventually be their undoing. “Don’t worry,” she told a friend, “I’ll not give up the fight. But I’d sort of like to win a round or two.”

She had another reason to keep going: she was growing ever fonder of Cruz. “I know how deeply you love your son,” Jalet wrote to Cruz’s mother that spring. “I have grown to love him also.” Just what kind of love she was professing was unclear, perhaps even to her. She certainly had deep admiration for his intellect and mental strength. She knew like few others how he suffered in prison—every day he stayed there increased the likelihood that he’d suffer a permanent injury or be killed. She had to help get him out.

But prison officials continued to make life difficult. One day Jalet showed up at the gates and was told she needed to find a notary and attest in writing that she was a lawyer. She presented her Texas Bar card but was told that wouldn’t be enough. On other occasions she’d notify prison officials in advance that she was coming to see a client, only to arrive and find that he had been put on a work assignment out in the fields, or that there had been an “incident”—a code word for a fight or a beating—and the inmate was in solitary or the hospital. Sometimes they’d just send her the wrong man. It was a petty game, but Jalet dutifully documented each instance in order to have a record of all the ways she experienced Texas prison officials trying to keep inmates from their legal representation.

Warden “Beartracks” McAdams had been transferred from Ellis to another prison, but the new boss, Robert Cousins, was just as harsh. For Cruz, or any of Jalet’s other clients, no offense or sign of disrespect was too small to be severely punished. One day, Cruz was called out by a guard when he tried to put his shoes on in the hallway. Not being allowed to put on his shoes in the hallway seemed foolish to him, and he said so.

Warden Cousins was called to the scene and was told that Cruz had disobeyed a direct order and called the guard a fool. Cousins declared Cruz was going into solitary “until he changed his attitude.”

“Don’t you want to hear what I have to say?” Cruz asked. Cousins grabbed Cruz by the throat and pushed him against the wall. “I’m going to tell you something,” he said. “I’m tired of putting up with you, and I’m tired of that woman coming down to see you. … You’d better tell her and those nigger-loving lawyers they better hurry up and get you out of here or learn to keep my name out of their God-damn mouth because if they don’t I’m gonna send you out in a pine box. … Somebody should have killed you a long time ago.”

Cruz was then thrown naked into a solitary cell.

The Case Against Jalet

Jalet began to get word that prison officials had started a concerted campaign to turn her few dozen clients against her. They would call her prisoners in one by one to cajole and threaten them; things would go much better for them, they were told, if they fired that lady lawyer.

Some buckled. Jalet would show up at the prison gates and be told that certain clients no longer wanted to see her. She began to receive sharply worded letters from prisoners dismissing her help and denigrating her character.

“Mrs. Jalet, I’m beginning to catch on to a few things,” wrote one prisoner. “Number 1 is that you have a personal grudge against the TDC and are using a few prisoners to help you get your foot in the door. … If you have any care or compassion for your clients, prove it to them by not returning and stirring them up.”

Donald Lock, an inmate she had met only once and didn’t represent, wrote to prison officials and the attorney general that Jalet had ordered three beatings he’d received. Lock, who was young and brutalized by guards and other prisoners, had been beaten repeatedly, but the idea that Jalet had ordered the assaults was absurd. More likely, Lock saw a chance to gain the protection of prison officials by accusing Jalet. “I feel that Mrs. Jalet should be barred from the Texas Bar,” he wrote. “I’m hoping you could give me a lawyer to help me with this matter.”

That fall, Freddie Dreyer, a building tender, took matters a step further by filing a suit alleging a conspiracy between Jalet and her clients to foment revolt in the prisons. Dreyer’s suit claimed Jalet was “interfering with the prison’s orderly operation, causing a breakdown in morale, teaching revolutionary ideas, and threatening prison security” by encouraging and assisting a small prison population of “lazy, agitating troublemakers.” Soon another tender named Robert Slayman filed a suit with remarkably similar language. Lock filed a third suit and was promoted to “trustee,” the second most powerful role a prisoner could have behind building tender.

Jalet began to get word that prison officials had started a campaign to turn her clients against her. They would call her prisoners in one by one to cajole and threaten them; things would go much better for them, they were told, if they fired that lady lawyer.

Reporters jumped to cover the new lawsuits. A September 14, 1971 headline in the Houston Chronicle read: “Inmate Claims Woman Lawyer is Agitator.” The cases, the paper reported, alleged that “a Houston woman lawyer was … teaching revolutionary ideas and threatening prison security.”

Jalet was certain that Beto was behind the suits. One prisoner Jalet had tried to help had told her that he had been offered parole if he would file a similar action. This latest tactic was a new low in Jalet’s eyes. “I put nothing past [Beto],” she wrote that fall to a NAACP attorney, “including murder.”

Jalet assumed the lawsuits against her would be dismissed. Not only did they lack any basis in truth, they didn’t have any basis in law. The prisoners were suing her under the same law that she was using to sue Beto and the Department of Corrections—one that protected people from abuse at the hands of officials acting with the power of the state. Judge Carl Bue, however, didn’t seem to mind that Jalet wielded no state power—he combined the three suits into one and allowed them to go forward.

Jalet had lost every legal battle she had fought so far. If she lost this one, she knew, it would be the end of her lawyering days in the Lone Star State.

Guaranteeing Tranquility

Beto’s new plan to rid Texas of Jalet was likely motivated by other factors, such as the country’s dramatic rise in prison riots. There had been just five in 1967, but that number had tripled the next year. There were 27 riots in 1970, and 1971 was on pace for even more.

On September 9, an uprising by nearly half of the 2,200 prisoners at the Attica prison in New York turned into a five-day siege that dominated the news. Prisoners took 42 prison officers and civilian staff hostage. By the time the uprising was quelled, more than forty people were dead, including ten prison guards and employees. The day the New York state police launched the bloody assault on Attica to retake control, Beto was a featured speaker at the national governors’ conference in San Juan, Puerto Rico. That Attica riot, he told the attendees, was a “tragic and horrible example of the convict-run institution.”

Not long after he returned to Texas, Beto decided for the second time to ban Jalet from his prisons.

“Your continued and frequent visits to the Department of Corrections as well as your correspondence with inmates make it impossible for me to guarantee tranquility within the institutions and the protection of inmates,” he wrote to Jalet. “Accordingly, effective this date, I am requesting all Wardens of the Texas Department of Corrections to deny your admission to the institutions under my general supervision and to terminate correspondence between you and any inmate in the Texas Department of Corrections.”

At this point, Jalet represented close to fifty prisoners. By fiat, Beto had deprived all of them access to their lawyer.

When Cruz heard what Beto had done, he likely knew he was in grave danger. Sure enough, a few days later, a building tender named Jesse Montague, who went by the nickname Bay City, appeared at Cruz’s open cell door.

“I guess you know they barred that woman lawyer from coming to see you,” Montague said. He dragged Cruz out of his cell and, with the help of another tender who held Cruz’s arms behind his back, beat him savagely with a blackjack. “No fucking greaser is going to take over my cell block,” Montague spat.

After twelve days in the hospital, Cruz was accused of assaulting Montague and put in solitary. He lost the few good-time days he had accumulated. He was looking at another seven years in prison.

As Cruz recovered, Jalet spent long days at her typewriter and on the phone trying to get support from anyone who could help her fight Beto. Prominent figures from the Texas Bar came to her aid. They may not have had much in common with her politically—indeed, they may not have even liked her much—but many of them saw Beto’s decision for what it was: an assault on the constitutional rights of lawyers to defend their clients. After a series of letters from prominent attorneys objecting to the restrictions put on Jalet, Beto reversed his decision and allowed her access to the prison.

But Beto was far from conceding the fight.

VI. THE BROKE-DICK FARM

In mid-November, Cruz was taken out of solitary and told he was being transferred. He was put into a car with Warden Cousins and driven through the Ellis gates. After a few miles they stopped on the side of the road, where Beto sat waiting in another car. Cousins got out, walked over, spoke with the director, then got back into the car.

“Do you know where you are going?” Cousins asked Cruz.

“I’m going in the right direction,” Cruz said to the warden, “because I’m getting away from Ellis.”

“I’m taking you to a place where you can confer with your attorney,” the warden responded. “She wants to see you.”

Cruz wasn’t the only one being transferred that day. The pressure on inmates to disavow Jalet had left her with about half of her fifty clients. The two dozen who had stayed loyal were being shipped to the notorious Wynne Unit, on the outskirts of Huntsville.

Ellis may have been known as brutal and violent, but the Wynne Unit was also despised. Among prisoners, it was popularly known as the “broke-dick” farm because it housed the mentally disabled and the mentally ill. For years the unit had been run by a warden who was generally viewed as compassionate. But that warden had been replaced by none other than “Beartracks” McAdams. As wardens often did when they transferred, McAdams had brought along his favorite staff—in his case, his most vicious building tenders.

Jalet’s two dozen clients were put together on the fourth tier of the B wing and collectively designated the “Eight Hoe work squad.” They were isolated from the rest of the inmates, even eating at different times. They were allowed no access to regular recreational activities or educational or rehabilitation programs. They worked six days a week and were given the most disgusting and backbreaking assignments, like shoveling manure and stacking telephone poles and railroad ties.

They were also doped up. Normally not known for providing attentive medical care, prison doctors began liberally prescribing powerful psychoactive drugs such as thorazine and librium to the Eight Hoe. This worried Jalet. Cruz, as a former heroin user, would be in particular danger of falling back into addiction, and Jalet counseled him to resist the drugs. This wasn’t medical treatment, in Jalet’s assessment, but another way to debilitate her clients.

From Beto’s perspective, collecting these inmates in one place must have seemed like a savvy move: prison officials could keep an eye on them and, by isolating them from other prisoners, keep them from spreading their seditious activities. They could be punished as a group and shown the error of their ways.

Beto and McAdams were also aware that requiring inmates of different races to live together was considered by most Texas prisoners a punishment in itself. At every unit of the prison system, racial segregation was strictly enforced. Surely, they thought, this mixed bag of Hispanics, African Americans, and Caucasians would tear each other to bits. Prison officials made some cells unusable and “double-bunked us,” remembers Eight Hoe member Lawrence Pope. “They made it a definite point to mix the races and [put] black with white, black with Chicano, Chicano with white, and so forth—this was to cause friction … They thought we were going to get in all kinds of difficulties, but we didn’t. We were very cohesive … very much in solidarity with each other.”

This wasn’t Beto’s only miscalculation. Grouping all the “writ writers” on the same cell block would turn out to be a big mistake. Jalet hadn’t just represented these convicts: she had taken the time to educate them about the law, to teach them that it was a tool they could put to use. Her clients began to share their knowledge and work together.

“In effect,” wrote one historian, “the [Eight Hoe squad] would become one of the most successful prisoners’ rights law firms in the country.” Beto had inadvertently created a jailhouse lawyer dream team.

There was James Grigg, who had served time in another state and knew the rules and regulations in other institutions. David Ruiz was a born street fighter who had no fear when it came to physical violence or taking the punishment that the TDC dished out. Lawrence Pope, a failed banker turned bank robber, was a middle-class white guy with good organizational skills and a remarkable memory for details. Alvin Slayton, the trained nurse, would tend to the Eight Hoe squad’s wounds and illnesses.

“[It was] the worst thing that [Beto] could have done. He got all the best brains together,” said Eight Hoe inmate Guadalupe Guajardo. “That’s where he messed up.”

These men were intensely loyal to Jalet. They knew the suffering she had gone through to represent them, and saw how tirelessly she worked. Many might have been enamored of her. But they all knew that it was Cruz who had the truly deep connection with Jalet. And Cruz led the group; he had basically been Jalet’s student for years and could quote her legal reasoning on any topic.

Within two weeks of being put together on the Wynne Unit, the two dozen members of the Eight Hoe squad had joined with Jalet and begun drafting a lawsuit: they were suing Beto personally for denying them their constitutional rights by barring Jalet from the prison and for punishing their attempts to access the court system through her. This time, Jalet would be named as a plaintiff, alongside her prisoner clients.

The Sucker Punch

On the morning of November 29, two guards moved the Eight Hoe squad out of the cell block for another day’s trip to the fields. There was a damp chill in the air, and the men stopped to rummage through a pile of jackets made available during cold weather. Donald Lock, the newly appointed trustee who was suing Jalet, walked up behind Cruz. As Cruz turned around, Lock landed a solid punch, breaking Cruz’s glasses and opening a gash on his face.

Richard Jimenez, another of Jalet’s clients, was the first to come to Cruz’s aid. Unlike the building tenders, Lock wasn’t much of a fighter, and seeing that Cruz had help, he backed down.

“Just you and me, Cruz,” he yelled from several yards away. Cruz knew not to take the bait. He stood silently, surrounded by members of the Eight Hoe, holding a handkerchief to his bleeding face.

Moments later, guards on duty broke up the confrontation and called for Jimenez and Cruz to step away from the group, saying, “We’re getting you two for fighting.” They ordered the rest to walk toward the gate for their work assignment but nobody moved. The Eight Hoe squad had been together less than a month, but in that moment they made a collective decision: they were going to stick together.

The Eight Hoe squad demanded to see the warden. The guard, seeing that he had lost control of the men, relented. Before he left to get McAdams, he yelled up to a guard on a watch tower to get his .30-30 rifle and “shoot anyone that moves.”

McAdams soon arrived with a cadre of his lieutenants. Eight Hoe member David Robles spoke up first. “Fred didn’t start the fight,” Robles said to McAdams, “he was jumped on by Lock. Jimenez was just trying to break it up.”

McAdams approached Robles and shoved him. “That’s a lie,” he said. “These men are going in the hole.”

“If you take them,” Robles said, “you might as well take me too.”

Robles, Jimenez, and Cruz were hauled off to solitary and the rest of the squad was forced out into the fields. Members of the Eight Hoe thought the fight had been an obvious setup, an excuse to punish Cruz and an attempt to break the morale of the others. But it had only helped solidify the bond among them.

The First Victory

Christmastime in Texas always seemed to bring bad news for Jalet and Cruz. This was the season when Jalet had gotten fired from jobs, when Novak died, and when Jalet most missed her children. But as 1971 ended there were good tidings. The appeal of the Novak case had been heard by a panel of three judges in the Fifth Circuit. Disagreeing with Judge Seals, they ruled that the Department of Corrections had abjectly failed to provide prisoners with adequate access to legal services and, because of that, prisoners shouldn’t be punished for helping one another.

“The TDC’s ban against inmate [legal] assistance cannot stand,” wrote one of the ruling judges. Another circuit court judge would later write that the Novak decision was “the first hint … that change was in the wind.” No longer would the practices in state prisons be “beyond the pale of [federal courts’] scrutiny and intervention.”

In the Novak ruling, the Fifth Circuit judges added that any loss of good time suffered for violating that unlawful regulation had to be restored. This was big news for Cruz, who had lost years of good-time credit for helping his fellow inmates. After a decade behind bars, he was looking at the possibility of getting out in just a few months.

The main event was still to come in 1972. If the two building tenders and trustee Lock won their suit against Jalet that claimed she was fomenting revolt in the prisons, she’d be disgraced and likely lose her right to practice law in Texas. But a victory by Jalet and the Eight Hoe squad in their suit against Beto would be equally significant. It would not only be a public shaming of the director of the Texas Department of Corrections; it would also signal that not even someone that powerful could get away with denying prisoners their constitutional rights.

Jalet was far from optimistic. She had landed yet another job, this time with the VISTA poverty program, but it brought in just $190 a month, barely enough to pay for food and her small Houston apartment. She owned no property or assets other than her 1967 Rambler, which was worth about $700. She had no money saved to hire competent representation. A team of six lawyer-members of the Houston ACLU came to Jalet’s defense—two to defend against each of the three building tender suits. They volunteered their time, but unavoidable court costs and expenses would nearly bankrupt the chapter.

Early signals from Judge Bue gave Jalet even more reason to be nervous. After a meeting with Beto, Bue had handpicked three heavy-hitting lawyers to represent the prisoners suing Jalet. One was Tom Phillips, the chief trial lawyer at one of the largest and most prestigious firms in Houston. The second, Donald Eckhardt, happened to be a lawyer from Bue’s old firm. The last, Max Jennings, had an office on the same floor where Bue used to be in private practice.

Bue guaranteed that the plaintiffs’ costs for their lawyers would be picked up by the federal government. Jalet, however, would get no financial help. Worse yet, Bue would be the presiding judge in both cases—the prisoner suits against Jalet would go first, and then he’d hear Jalet and the Eight Hoe’s case against Beto.

“I truly believe that the judge is in a conspiracy with Beto and the attorney general and the wardens to finish me,” Jalet told a friend.

VII. CRUZ ON THE OUTSIDE

While Jalet and Cruz awaited the start date of the trial, two monumental events occurred.

On March 20, 1972, the United States Supreme Court ruled on Cruz’s freedom of religion lawsuit—the complaint Cruz had written on toilet paper while in solitary. They ruled that the State of Texas had “discriminated against [Cruz] by denying him a reasonable opportunity to pursue his Buddhist faith.” However, since the case had never had a full hearing, all the Supreme Court could do was direct the lower courts in Texas to hear it. As far as anyone knew, it was the first case written on toilet paper to be considered by the Supreme Court of the United States.

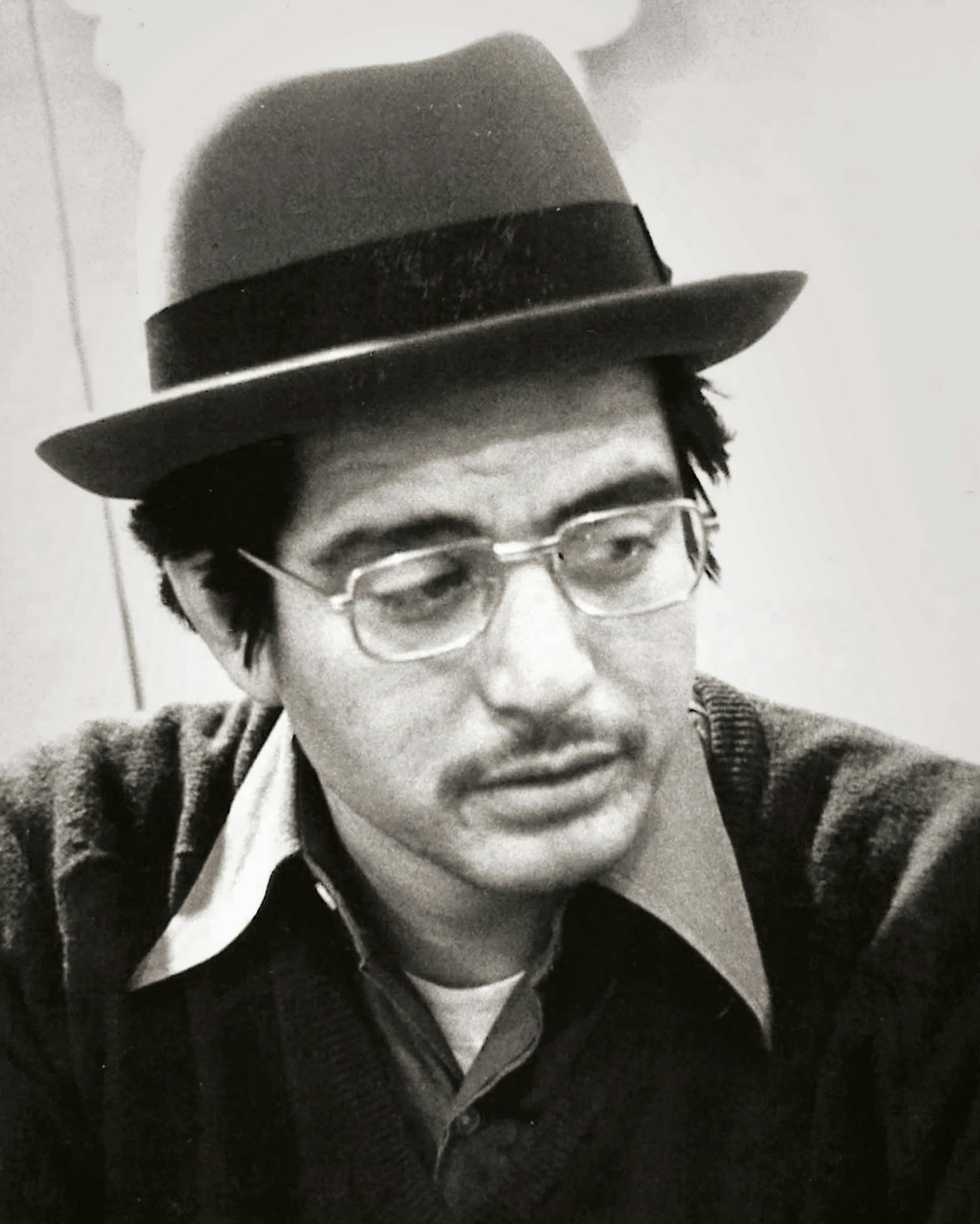

The second remarkable thing was that Fred Cruz was given back the good time he had lost. Subtracting those days from his fifteen-year sentence showed that he was overdue for release. On March 9, 1972, he walked out of the prisoner processing center in Huntsville. Now there were no bars, wire-mesh screens, or reinforced glass separating him from Jalet.

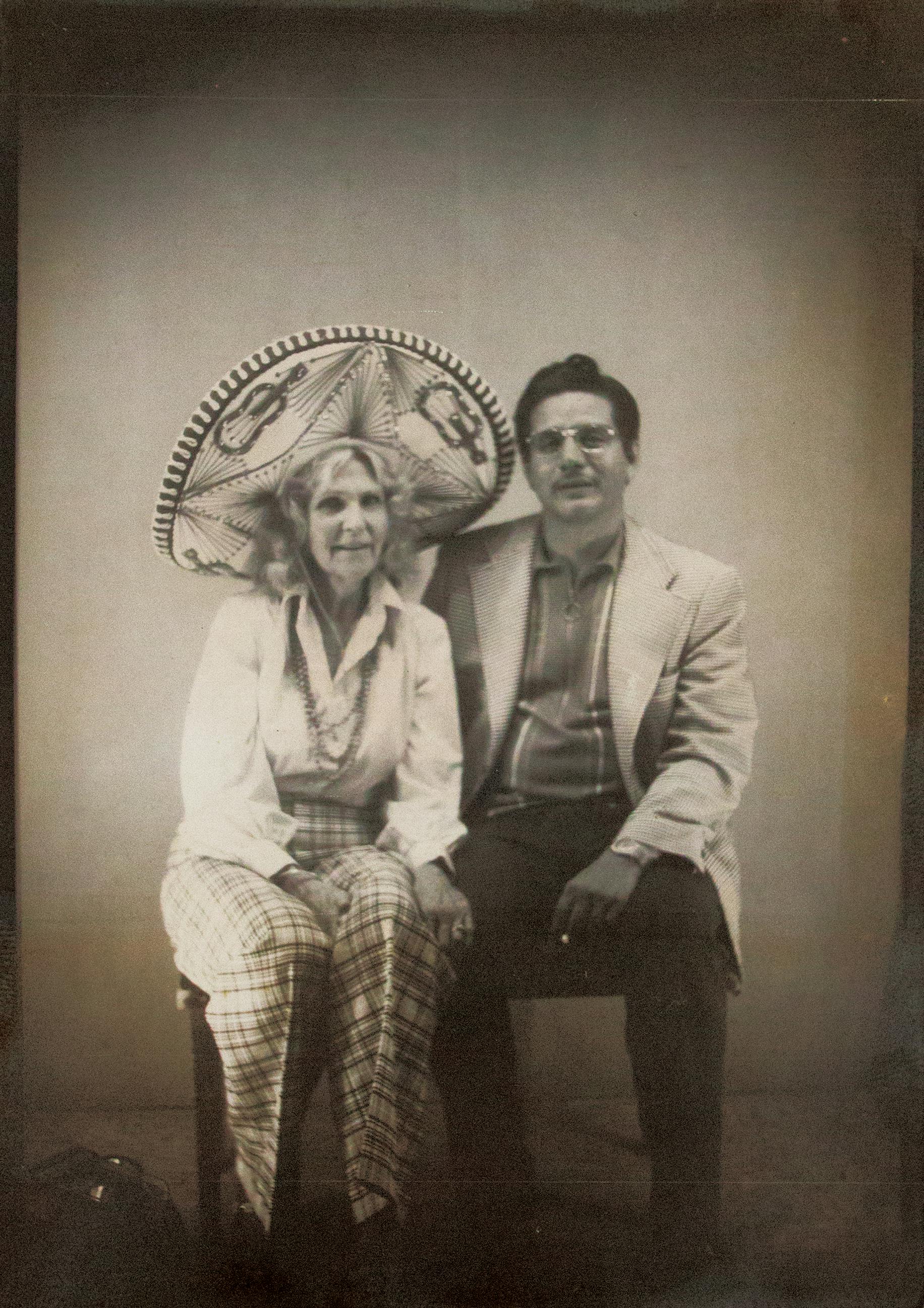

Since they had met in the fall of 1967, Jalet and Cruz had kept their relationship strictly professional. Now that Cruz was free, they could admit that they had fallen in love. A month later—just days before the start of the trial that would determine the fate of Jalet’s career—they drove across the Mexican border to the little town of Colombia, Nuevo Leon, and got married.

Their marriage was big news when Jalet’s trial commenced the following Tuesday. The ACLU lawyers were stunned, and all the papers ran stories on the salacious turn of events. “She Helped Free Him, He Marries Lawyer,” ran one headline. Jalet and Cruz’s age difference was always emphasized. The Houston Chronicle even put it in their headline: “Woman Lawyer, 61, Weds Ex-Con, 32.” There were also references to the differences in their educational backgrounds. “Mrs. Jalet, a Radcliffe graduate, said she and Cruz, who has an eighth-grade education, were married in Mexico Saturday,” wrote the Chronicle reporter.

Jalet had known the marriage would raise questions about her motivations. She told reporters and colleagues, as well as her daughters and friends, that she and Cruz had never discussed their feelings for one another until after Cruz’s release; since all of their letters were read by officials and many of their in-person conversations were monitored, the topic was likely never raised beforehand.

Still, reading between the lines of hundreds of pages of correspondence, one can clearly see a deep connection building over time. “Their intimacy grew from their mutual love of the law,” Frances Jalet-Miller, one of Jalet’s daughters, said years later. “They saw its beauty. It was their shared passion.” Jalet and Cruz had a shared commitment to their cause, and through it, their minds and hearts began to synchronize. Theirs had been a courtship where they showed devotion by withstanding deprivations, public humiliations, and many dark and uncertain hours. Although they were from radically different backgrounds, they had both spent their lives being underestimated and put down. In the other, they had each found a champion.

Jalet on Trial

The surprise marriage wasn’t the only remarkable occurrence that first week. Robert Slayman, one of the three prisoners suing Jalet, got his release from prison on the second day of the trial—likely as his reward for filing the suit. Then he up and disappeared. Now that he had his freedom, he apparently saw no point in continuing the farcical lawsuit claiming that Jalet was some revolutionary mastermind.

Dreyer and Lock, the other two prisoners suing Jalet, played their assigned parts—at least in the beginning.

On the stand they swore that Jalet, through Cruz, had encouraged her clients to join a conspiracy to take over the prison. They portrayed her as a dangerous ringleader of a group intent on revolt. Other building tenders were also brought in to testify. Julius Dwayne Perry said that Jalet had told him that riots like the one in Attica were necessary. “Sometimes we must suffer to open the eyes of the public,” he claimed she told him. Another building tender testified that Jalet had suggested he murder another prisoner.

Warden McAdams then testified to how Jalet stirred up the prisoners, making them more dangerous and less compliant. “After one or two visits,” he said on the stand, “there was more work stoppage, more fights, more tension, more men in solitary.” McAdams testified that under Beto’s rule, Texas prisons had transformed from an institution rife with sexual perversion, drug use, and violence to a modern institution where inmates were educated and rehabilitated. He even brought pictures to show the judge the improvements in the facilities. All of this good work, he testified, was threatened by Jalet’s interference.

The lawyers cross-examining McAdams asked him about the many abuses Jalet had documented with the help of her clients. He denied them all. Were prisoners ever punished for minor infractions of unwritten prison rules? Were they ever beaten with baseball bats or blackjacks? Were they ever hung from the bars with straitjackets? Were they made to stand on rails or stomped on while handcuffed? Were building tenders used as enforcers? Under oath, McAdams testified that none of it was true.

To counter McAdams’s anodyne picture of the Texas prison system, Jalet’s attorney introduced a book of photographs by Danny Lyon that had been published the year before. Beto had given Lyon an open pass to take pictures inside his prisons for fourteen months beginning in 1967. Lyon’s black-and-white photographs catalogued the daily realities of a world of forced labor and despair.

At the beginning of the second week, Jalet took the stand. She could not have looked less like the violence-prone Svengali described by the tenders; it was almost comical to imagine this well-spoken lawyer saying that somebody “needed killing.” Under questioning, Jalet denied that she had ever encouraged open revolt or advocated for the beating or murder of prisoners.

There was virtually no evidence—outside the outlandish claims of the building tenders themselves—that Jalet had ever done anything besides represent her clients. The TDC had monitored her letters to and from prisoners for four years, and in all that correspondence just one line was out of character: while Beto was conspiring to get Jalet fired from her first post in Austin, she had written that she wanted to “lash out at … the whole prison system.” It was a rare show of anger, but hardly proof that she had organized a conspiracy.

With no proof that Jalet had actually done anything she was accused of, the lawyers for Lock and Dreyer had to resort to hypotheticals. What if, they asked Jalet, one of her clients had told her they were planning a murderous prison riot? How would Jalet react?

Her first reaction, she told the court, would be to be upset. She said she would then counsel the prisoner against the plan and tell him she would not be a part of it. The lawyers made much of the fact that she did not say she would immediately inform prison authorities of the pending riot—never mind that the situation was entirely hypothetical.

The plaintiffs’ lawyers got Jalet to admit to having attended talks by renowned prison rights lawyer William Kunstler and marching in a protest against the Vietnam War. They also brought up her marriage to Cruz to impugn her motivations. But by the time Jalet got off the stand, the lawyers had little to show for their questioning.