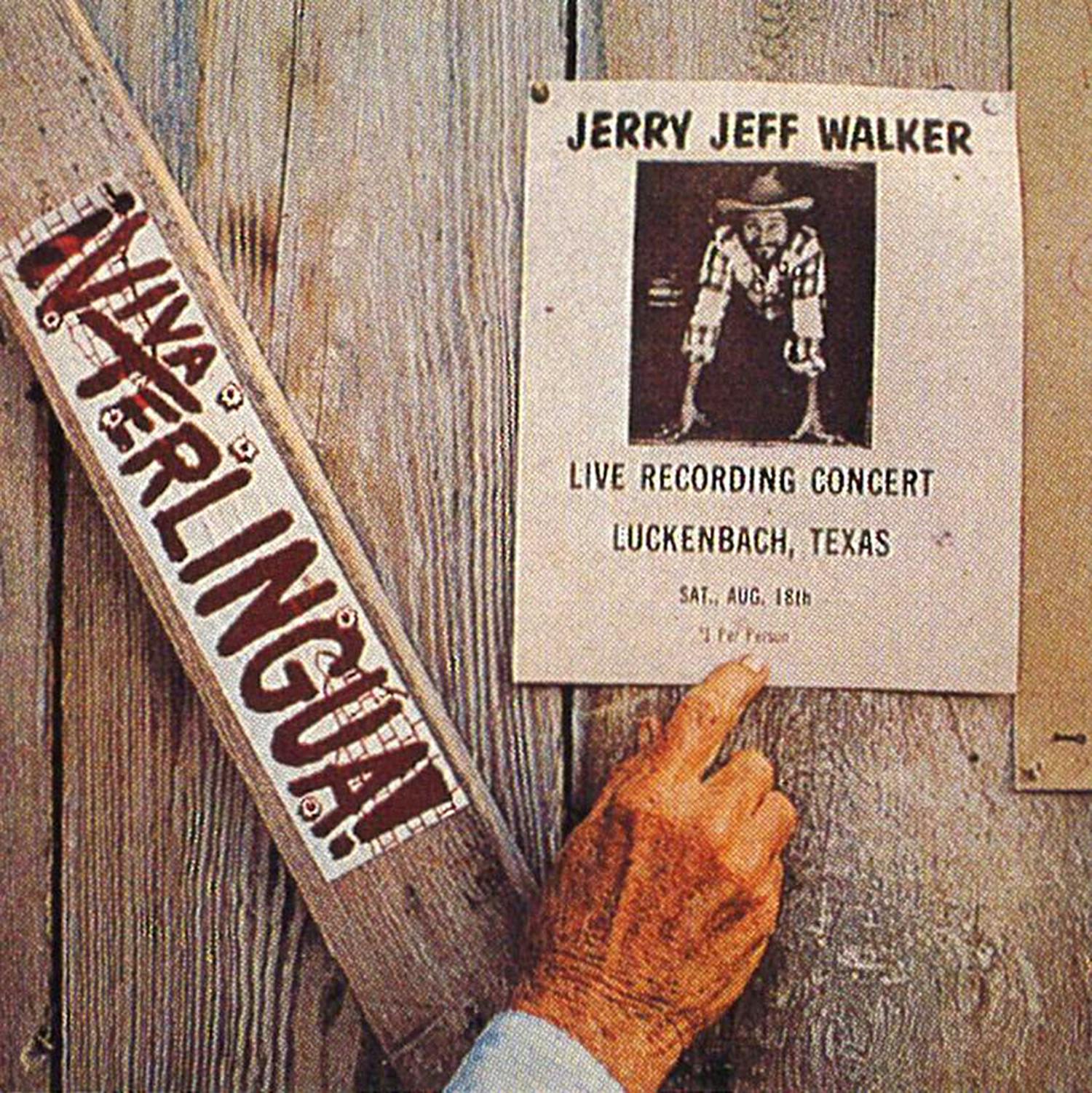

A few gray-haired gents stood outside the Luckenbach saloon with their shoulders hunched against an October night’s chill. There was a distinct air of unease among them. Across the road in the dance hall of Luckenbach, a quaint hamlet near Fredericksburg, Jerry Jeff Walker was trying to recapture what these men remember as a magic time in their lives. Here, in August 1973, Jerry Jeff and the Lost Gonzo Band recorded ¡Viva Terlingua!—the album title borrowed from a chili cookoff bumper sticker that was stuck on the saloon’s wall. That record, and a wild Saturday night concert, signaled a Texas music boom and countercultural uprising. Willie Nelson was the only Austin performer of that time who became a national star, but only Jerry Jeff could mix a clarinet and steel guitar and come out with rock and roll. As time went by, the weekend’s high jinks took on a revered, legendary aura. Now, twenty years later, Jerry Jeff had returned to play a ballyhooed Friday night concert for old friends and new admirers and to record a sequel album called ¡Viva Luckenbach!

The graybeards were, in the parlance of those bygone days, trying to get off—to memories, nostalgia, expectations—and their boot heels felt like lead. Among them was Steve Fromholz, a singer and lyricist who in 1973 also dreamed of gold records and stardom but settled for a stable, productive mid-life as a solo performer, actor, and wilderness river guide. A few minutes earlier, Fromholz had sat in with Jerry Jeff’s band and contributed a song meant for the new album. Now he looked across to the dance hall as Jerry Jeff and the Gonzos howled the chorus of “Up Against the Wall Red Neck,” which had set off a crowd frenzy at the concert two decades ago. “It’s so sedate in there,” Fromholz marveled. “The only ones drinking hard are me and the sound man.”

Doctor’s orders, divorces, survival instinct—many things had intervened over the years. Besides, did anyone really want to roll back the clock to that distant hour? Jerry Jeff landed in Austin two decades ago with several folk records behind him, one classic songwriting credit (“Mr. Bojangles”), and a gift onstage for falling over backward into the drums. He seemed to think that only outrageous behavior or an early grave certified his talent. He abused band members, club owners, his audience, and the affection and furniture of friends who wanted to go on believing in the goodness of his heart. “Y’all sure been good to me,” he mumbled at the end of one especially sodden and chaotic Austin performance long ago. “If I’da been in your place, I’da shot myself.” Back outside the Luckenbach saloon, these friends’ conversation naturally turned to Jerry Jeff’s penchant for getting pummeled. “Everybody beat him up; he didn’t leave you any choice,” said Gary Cartwright, a senior editor of this magazine. “The best time,” writer Bud Shrake reminisced, “he was playing the National Finals Rodeo in Oklahoma City. Some bull riders cornered him in a hotel suite, kicked him, and tied a rope and cowbell around his neck. Jerry Jeff got up and followed them to the elevator. He said, ‘You guys ain’t so tough. I got beat up a lot worse than this last week by some bikers in New Orleans!’ ”

In 1973 Jerry Jeff had a contract with a major label, MCA, whose executives encouraged him to take chances. He hated recording studios and his sidemen feared them, so he borrowed the Luckenbach dance hall owned in part by his hero, Hondo Crouch, the late rancher and self-appointed mayor of Luckenbach. With hay bales for baffling and a mobile sound truck manned by New Yorkers who camped beside the creek, the musicians plied their craft during the day and retired to their vices and Fredericksburg cabins at night. The material was a mix of old Jerry Jeff songs, new ones still being composed, and astute borrowings from other Texas songwriters. Customers of Hondo’s beer joint (which passed for a Hill Country salon in those days) drifted through at times. The tranquil getaway became an event when Jerry Jeff advertised a Saturday night concert, admission $1. The arrivals that day featured an Austin in-crowd of writers, artists, lawyers, and political activists, among them Ann Richards. (On the LP’s lyric sheet is a photograph of the future governor at the picnic table where the hardy hung out all day.) By dark the crowd had grown to nine hundred. The tiny dance hall was so packed that people crawled up into the rafters and stood six deep outside the open windows.

For the sequel recording and concert, Jerry Jeff perched on a stool with a cowboy hat and a guitar, showing none of the scrufffness of yore, and his voice was steadier and more disciplined. “What it is is what it is,” he says of ¡Viva Terlingua! “Trying to do all that and drink all the time was real hard. I think I’m singing ten times better now than I ever did.” It wasn’t just booze, of course. In the late seventies and early eighties, his career and life were almost undone by Thai sticks, speed, cocaine, bill collectors, and the legend itself. Jerry Jeff still wobbles off the straight and narrow on occasion, but in large part he cleaned up his act with a vengeance. He jogged, he fasted, he hung upside down from a tree because somebody told him that was a healthy thing to do. He exhibits none of the bitterness one has come to expect of the has-been and faded star; he is thankful to enjoy a present tense at all.

In fact, since his shrewd and striking wife, Susan, took over his management, Jerry Jeff has made a remarkable comeback. Along with the voluminous royalties of “Mr. Bojangles,” he has his own record label and access to a mailing list with thousands of names. Susan and the staff use the list for a Jerry Jeff newsletter and for direct-mail offers of CDs, tapes, T-shirts, and memorabilia. Although his records receive virtually no airplay, Jerry Jeff is making a lot more money these days; he travels to distant concert dates in his private turboprop. Throughout the country he has a cult following of college kids influenced, he thinks, by dads and older brothers who were cosmic cowboys in the seventies. These kids, derided by some of the old guard as fraternity kickers, made up about half of the crowd at the Luckenbach revival. Buying tickets offered only through the Jerry Jeff fan club, they paid $50 a head.

As with ¡Viva Terlingua!, starting at midweek Jerry Jeff and the band made sure they essentially had ¡Viva Luckenbach! in the can before the crowd showed up. Ironies resonated during the Friday concert. Instead of good times and rough edges, a premium was put on tight control and a polished product. At dark, security guards sealed off the road into Luckenbach, and the well-screened crowd was limited to three hundred. Everybody was seated at a numbered table. Beginning at eight o’clock, the musicians laid down an acoustic track, with backup vocals and electric guitars to be added later. Jerry Jeff’s favorite of this material was “The Gift,” an autobiographical ballad filled with longing for a guitar his grandma gave him, the year of fasting, his loving family, and a home built on a hill. (The rock and roll endpiece, “Movin’ On,” sounded like the hit to those who preferred the jumpier days.)

After a break, the players plugged in their amps, but still it seemed that Jerry Jeff preferred the folksinger mode. Throughout the evening, lamentations were heard for the lost madness of the good old days. And Jerry Jeff was often reminded of the entrapments and price of his cult status. The kids were drawn to him in part by tales of the outrageous antics he has tried to live down and move beyond, which has taken him half of his adult life. He has grown up, but these kids can’t appreciate what that has meant for Jerry Jeff. Sometimes they yell at him and, just as he did in his drinking days, he loses his patience and abuses their affection in return. In the spirit of ¡Viva Terlingua! and its generation, these kids also began to get drunk and assert themselves. “I want to thank you all collectively, ” said Jerry Jeff, with a glance toward the rowdiest contingent, “for coming and not yelling ‘Pissin’ in the Wind.’ ”

“Yahh! Yahh!” bellows erupted. “Play it! Play it!” Jerry Jeff finished out with “Mr. Bojangles” and a splendid version of Leadbelly’s “Goodnight Irene.” He said later that a nice and tender mood prevailed, and he didn’t want to get rambunctious and spoil it. (He and his sidemen came away convinced that they had made a better record the second time around, and judging from the smooth performance, they may be right.) Fifty bucks or no fifty bucks, he declined to play an encore. Some kids had just arrived, expecting of Luckenbach’s dance hall the same showtimes as the bars where they hang out in Austin and San Marcos. A young woman at table 32 stared at her second slice of pizza. “He’s not through, is he? I want my money back. I don’t believe it.” It was eleven o’clock. Bedtime for Gonzos.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Music

- Jerry Jeff Walker

- Ann Richards

- Fredericksburg