Country music, if you believe all the critics who have misread a recent movie called Nashville, is made up entirely of smarmy concoctions of drink, divorce, Fundamentalism, and other cheap, un-chic subjects. Country musicians, if one subscribes to Nashville’s credo, are perhaps one generation removed from cave dwellers. Their primitive musical instincts reveal themselves in cretinous tunes that parallel their wretched lives lived out in an alcoholic daze. Their existence is bounded by ’52 Buicks, trailer parks, and divorce court.

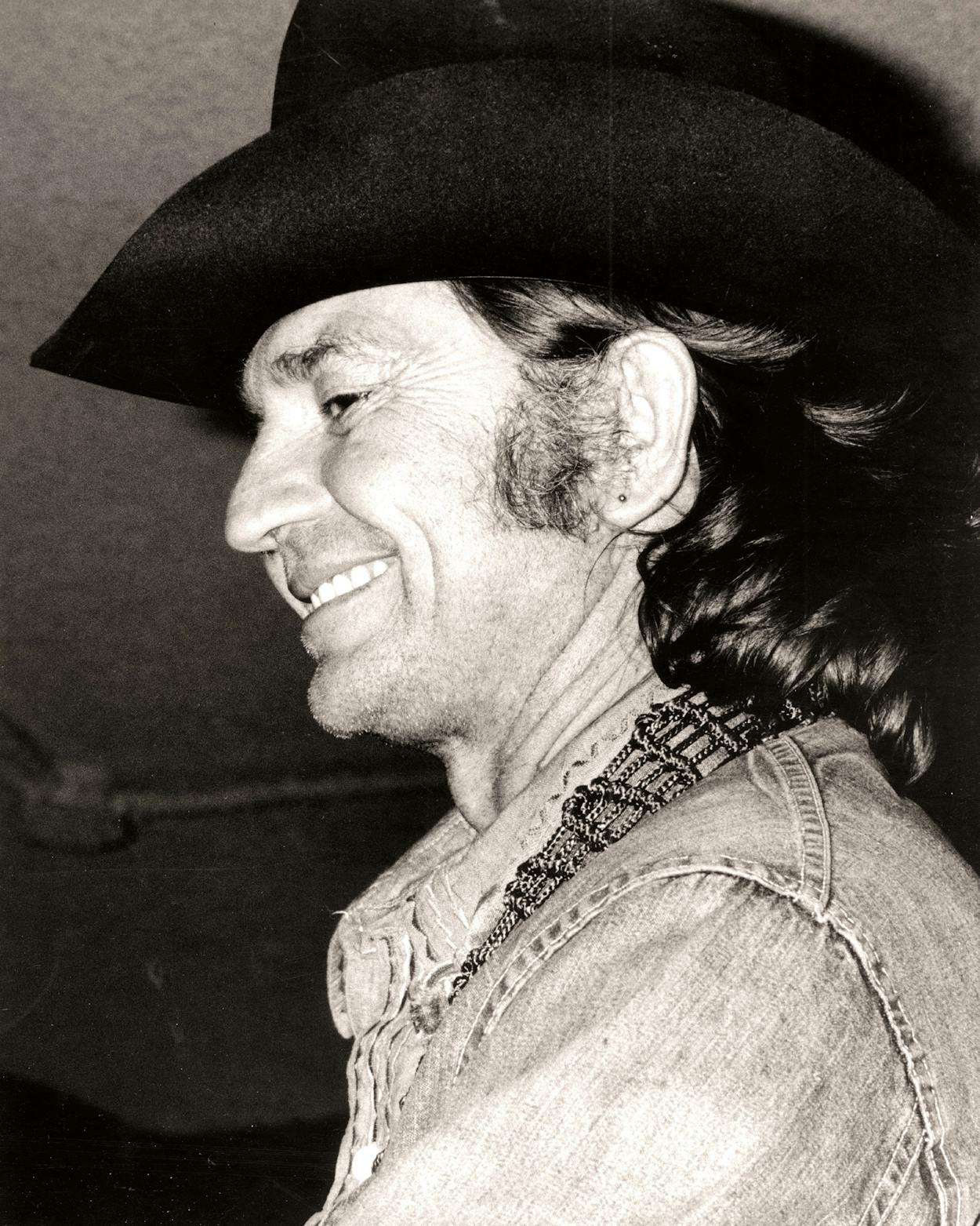

Country music sometimes may reflect such a life—but it is much, much more in the hands of its few truly gifted songwriters. The best of them—and this will come as no surprise to Texans—is a man named Willie Nelson who has recently recorded an album so remarkable that it calls for a redefinition of the term “country music.” The difference between Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger and any other current C&W album, and especially what passes for a soundtrack for Nashville, is astounding. What Nelson has done is simply unclassifiable; it is the only record I have ever heard that strikes me as otherworldly. Red Headed Stranger conjures up such strange emotions and works on so many levels that listening to it becomes totally obsessing. The world that Nelson has created is so seductive that you want to linger there indefinitely.

Basically, Stranger is a morality play that has a lot to do with honor and integrity and revenge and style and good and evil and God and the universe. The story line, on the surface, is this: the Stranger’s woman leaves him for another man, he tracks them down and kills them; in tormented mourning he rides aimlessly and wildly and shoots a woman who tries to steal the “dancing bay pony” that had belonged to his woman; along the way he undergoes a massive catharsis, an emotional death and rebirth and eventual salvation and acceptance of life through another woman he meets. Together, they build a new life. A simple plot, to be sure, but Nelson’s telling of it is extraordinary. The music industry term “concept album” is inadequate. Stranger is more a revival of the oral tradition, of the storyteller who preserves and passes on the beliefs and teachings of a tribe or group.

Nelson has given hints for years that he was capable of assuming such a role. Of all contemporary songwriters, he has most effectively observed and interpreted life around him. The master of despair, the poet of honky tonks, the chronicler of personal apocalypse—he has been called all of these and they are all accurate. After all, any man who could write a touching song about a man strangling his lover, another in which a despairing solitary man talks to the walls, and yet another with the remarkable title “Darkness on the Face of the Earth” is a man who walks close to the edge. That in itself is not unusual in country songwriters. Since the days of Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter family right up through Hank Williams to Merle Haggard the music has dealt with the life the songwriters knew and they depicted it in realistic terms. There has been little escapism in country lyrics and almost no fantasy. It’s been largely grim music that dealt with life’s central problems: problems with the job down at the plant, marital difficulties, hopelessly transparent love affairs, sordid one-night stands, and endless troubles with the bottle.

Musicians like Willie Nelson have refined these themes. Country music, as it broadened its horizons and pushed against its boundaries, had begun to attract a new generation of listeners and a cluster of young songwriters. Nelson remains the doyen of the new school, as he proved with his last album. Phases and Stages was the compassionate account of the dissolution of a marriage, which gave extremely sensitive male and female viewpoints. It, again, was labeled a “concept album” but I would call it a musical documentary.

I notice with interest that a single release off Stranger, “Blue Eyes Crying In the Rain,” has made a small noise for itself on the country charts. What’s astonishing is that Nelson, the master storyteller, did not write that song (Fred Rose of Nashville did); nor did he write much of the material on Stranger. He anthologized songs that span decades of American musical history and amazingly, once they were put together, they formed an unbroken tale. The effect is the same as if the entire album had been written at one sitting.

Nelson’s transitional device is his own “Time of the Preacher Theme,” with variations. The album opens with his weary, voice-of-a-prophet tale: “It was a time of the Preacher, when the story began, of the choice of a lady, and the love of a man. How he loved her so dearly, he went out of his mind, when she left him for someone, that she’d left behind.” *Timeless elements, these, and a classic basis for tragedy: romantic triangle, wronged lover, moral teachings, and inevitable revenge. The imagery, like the music instrumentation, is sparse and bleak: the wronged man “cried like a baby and screamed like a panther in the middle of the night. It was a time of the Preacher, in the year of ’01. Now the preachin’ is over, and the lesson’s begun.”*

The next song—or movement or chapter or whatever these installments should be called—is about mourning and garment tearing and smearing of ashes on one’s forehead and the profoundest grief over the loss. “I couldn’t believe it was true, O Lord,” sings the Stranger. If you’re of the opinion that Nelson’s morality play parallels the Book of Genesis, the retelling of it in frontier terms yields a surprise. Instead of reconciling himself to being cast out, the Stranger burns with an inner fire and could not possibly refrain from tracking down and shooting the woman and the viper who ended his happiness.

The Stranger “could not forgive her, though he tried and tried. And the halls of his memory still echoed her lies. He cried like a baby and screamed like a panther in the middle of the night. And he saddled his pony and went for a ride. It was a time of the Preacher in the year ’01. Now the lesson is over, and the killin’s begun.”* Revenge is his. But after he slays the woman and the other man, revenge is not enough. With his “eyes like the thunder,” the Stranger rides hell-bent to nowhere, like some terrifying Death Angel on his black stallion. He senses, in the throes of bitter remorse, that he can regain innocence lost, that he can again know the happiness that was his. He does not know how but, eventually, through resisting a false savior (a temptress whom he shoots), he comes to recognize and finally accept his fate. Side one ends with “Just As I Am,” the timeless and haunting gospel of total surrender to God.

On side two, he finds his reward in the form of a woman who will accept him: “With no place to hide, I looked in your eyes. And I found myself in you. I looked to the stars, tried all of the bards. And I’ve nearly gone up in smoke. Now my hand’s on the wheel of something that’s real. And I feel like I’m going home.”** Closing the tale is a pastoral guitar instrumental, “Bandera,” that suggests a vision of a second Eden.

Listeners with a sense of whimsy may want to file this record, this Willie Nelson Version, next to the King James or the Revised Standard Version.