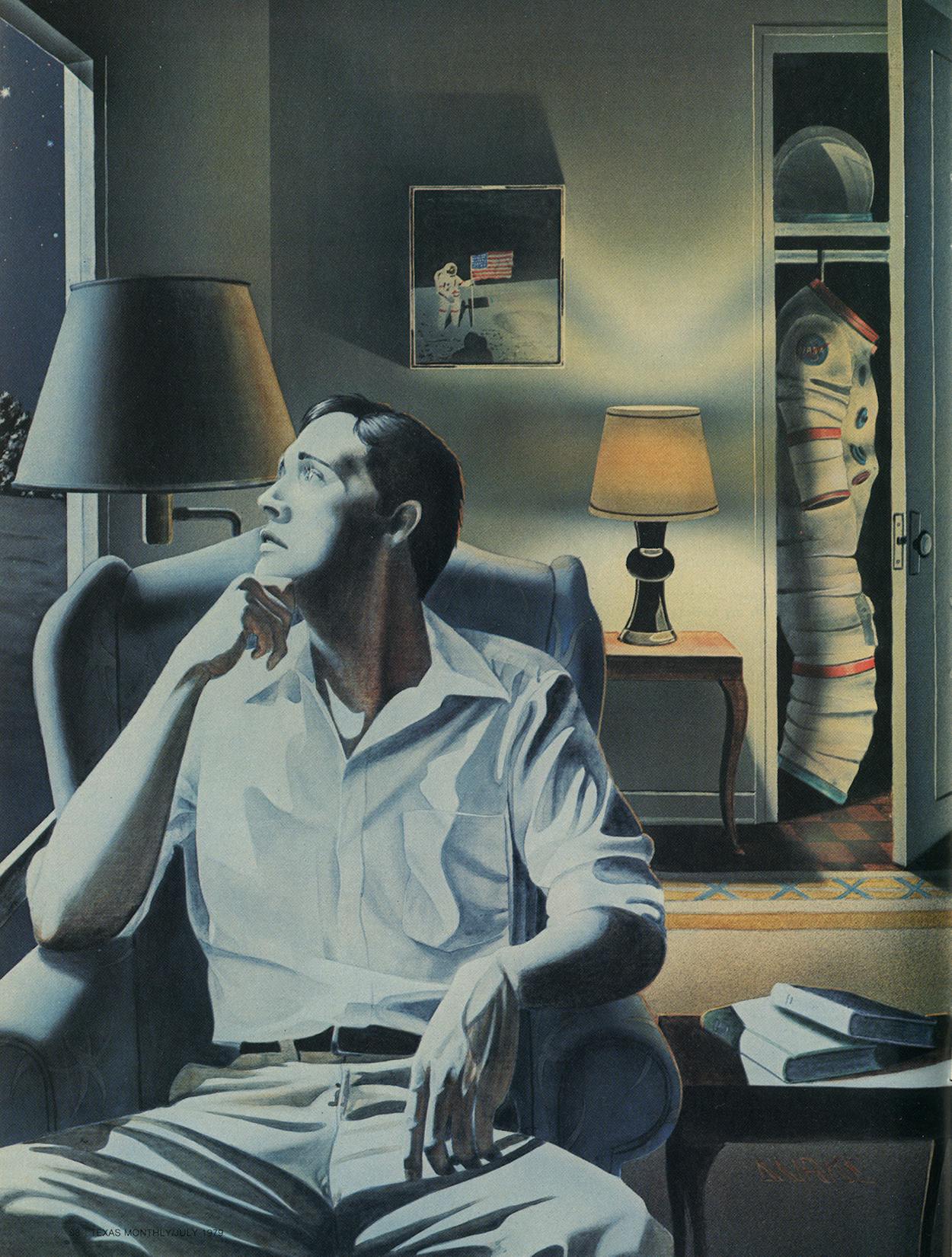

They had all seen the Moon before, of course. Indeed, there was never a druid more obsessed with the Moon than the astronauts in the Apollo program; no fertility cult with greater devotion. For thousands of hours apiece they had actually rehearsed going there—following their checklists, maneuvers, reacting to every situation the computers could conceive of—all under the most rigorous conditions that science could devise. If they “crashed” their simulator, they even had to report to the Accident Investigation Board to explain themselves. Dressed in outlandish costumes, they had lurched aroudn the Arizona desert, pretending it was the Mare Tranquillitatis, carefully gathering odd chunks of granite as if they were lunar samples. For years they had made believe, with precision and with dedication, yet they always knew it to be unreal. It was the Moon alone that gave meaning to the lives of Apollo astronauts, so when they saw it at night they must have genuinely yearned for it.

Among those men who went to the Moon, even the most insensitive of them, there were certain moments they recall in common, profoundly arresting moments that were stamped alike in their 24 separate lives, during nine different missions. One of these was that scene, three days out and afar in space, when they first turned and saw their destination.

They had last seen it the morning they launched—still fairly high in the Florida dawn and still far away—if they were lucky. “It was just by accident I saw it,” remembers Ken Mattingly, the command module pilot on Apollo 16. “Being command pilot I was sitting in the center seat, so that meant I climbed in last when we boarded. I didn’t have anything to do but stand around while the other guys strapped in, so I thought, well, I’ll just walk around some. So I walked over to the side of the launch platform and looked down at this big booster. I’d done that many times before, but it never had quite the same sensation as it did then.

“The gantry had been pulled back so the booster was sitting there all by itself, steaming and venting. At no other time does it have all the consumables on board, the oxygen and hydrogen that are causing it to have this appearance. And there’s no other structure around it. It’s just a rocket. There’s frost on the sides of the cold cryogenic tanks, and little vapors puffing out. And there’s an eerie silence. Normally when you’re out on the pad during any of the previous checkout operations there’s a lot of noise—machines running, elevators moving, people clanging and banging and talking. I was wearing my pressure suit, of course, which puts you in sort of an isolated environment already. There was no sound except for the little hum from my suit ventilator, and no one to talk to. Little puffs of the vapors would float by. You almost had the feeling: it’s alive!

“That sight was the first thing that was really different, that struck me, that said: You know today it is different. Today is not the game we’ve been playing in training for years. This is reality.

“From that point on, everything was unique. I climbed in; got strapped in; they closed the hatch. I don’t remember how long we spent on the pad before launch, but there’s a long period where you’ve done all the things you can do in the cockpit and you just have to wait. So I looked out the window at this point—I looked out and doggone if the Moon wasn’t visible in the daylight. Right straight out the top of the window! And I thought, ‘My God, that’s where we’re going. Today. For real.'”

“Most of the astronauts, though, had their last glimpse of an earthly Moon the night before, just before entering the windowless rooms of the quarantined crew quarters. Without exception they slept easy on that last night: they were that sure of themselves. Awakened after six or seven hours, they began the hurried ritual of physical exams, eating, suiting up, final briefings, last-minute checkouts. By the time they left their quarters they had reviewed, for the thousandth time, the entire launch procedure. They had also been pre-breathing pure oxygen for several hours, so they felt a shade giddy as they waited atop their Saturn rocket: 36 stories tall and filled with chemicals that can’t exist together, primed to explode in an organized way. And they saw no Moon.