Randall Jamail, the founder of Houston’s Justice Records, jiggles and jumps, takes a phone call, props a running shoe on a mixing board in Seattle’s vaunted Bad Animals Studio. He wears dark gray shades and his haircut is half an inch long. He hangs up, bolts down the hall to refill his cup with the studio’s “heroin coffee,” as he terms it, then hurries back and plays frenetic air guitar beside his hip, explaining the song’s arrangement to a musician. The 39-year-old Jamail is the son of famed Houston trial attorney Joe Jamail, a longtime chum of Willie Nelson’s. The younger Jamail grew up around Willie’s gigs and Fourth of July picnics; after college he graduated from law school, planning to join his dad’s firm, but that’s a hard act to follow. He launched Justice Records as a jazz label in 1989 and had fifteen Top Ten hits in three years. But the jazz share of the record market is minute, so Jamail branched out, signing blues singers, then county and western artists, followed by punk rock acts and recording a concert by London’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and an oration by Pope John Paul II—part of the Vatican’s first official acknowledgment of the Holocaust. Jamail also landed two of Willie’s albums, Moonlight Becomes You and Just One Love, when changing country and western fashion left the legendary Texas singer without a recording contract on a major label. Now it’s July 1995, and Jamail is engrossed in his latest long jump: Turn the nation’s top punk and grunge rockers loose with Willie Nelson material. “Outlaw to outlaw,” he frames the concept. The new record, scheduled for release later this month, is called Twisted Willie.

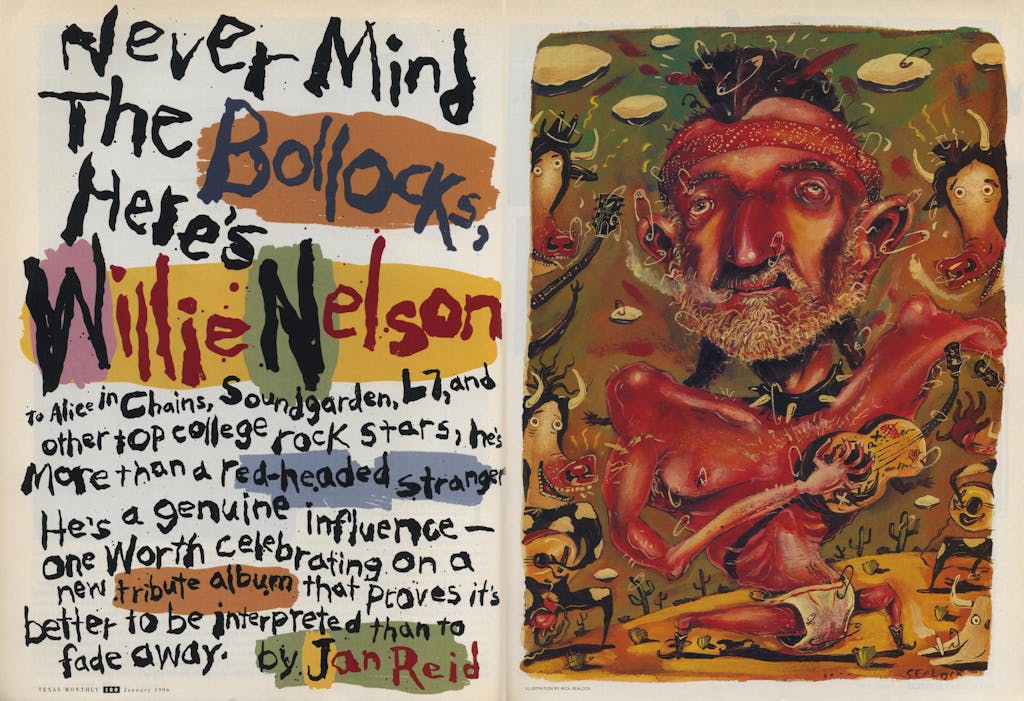

The lobby walls at Bad Animals Studio are lined with framed platinum records of Nirvana and Pearl Jam—Texas possesses no studio remotely like it—and one spin across the Seattle radio dial offers more evidence that this lush, fashionable, traffic-crushed city has become one of the country’s true music capitals. Yet grunge rock, the nihilistic evolution of punk and heavy metal that spawned the Seattle scene, began as the antithesis of commerciality. Nirvana and other groups put out albums on independent labels that, with no help from MTV videos or radio push of singles, spread word-of-mouth, took a large, youthful audience by storm, and made the major labels’ producers come to them, hats and contracts in hand. What’s that go to do with Willie Nelson? Precedent. “It’s like twenty years ago,” Jamail says, “when Willie was all but run out of Nashville. He came back to Texas, set up in Austin, and said, ‘I’m going to do what I do. And if the big record companies don’t get it, screw ’em.’ That’s exactly how it happened in Seattle.”

Willie’s career has looped, circled, and doubled back over so many times it’s akin to a trick roper’s routine. When the Nashville-based country music industry shunned him as a performer in the early seventies, he built his audience with tireless road appearances that filled rowdy halls with bankers, hippies, bikers. Their record-buying power changed the industry—suddenly it was all right for traditional country to rock and roll—and made Willie a superstar, along with his rough-edged Texas soul mate Waylon Jennings. But since then, the style they inspired has been burnished and slickened into the “hot country” sound that today drives the Nashville industry—hokum pop with a soft-rock dance beat. Willie and Waylon are old guys, they don’t prance around in tight jeans, and in the cities, country and western deejays just won’t play their records. And their 1985 tour and record with Johnny Cash and Kris Kristofferson as the Highwaymen did little to bolster their standing in the C&W market. To Nashville executives, they seem to be mere nostalgists.

But not to a younger generation of alternative-rock musicians. Jamail’s proposal of a radical interpretation of Willie’s songwriting, with contributions from each of the Highwaymen, has set off a stampede of big-name rock performers to get on board: members of Seattle grunge heavyweights Nirvana, Alice in Chains, Soundgarden, and Screaming Trees. Lollapalooza tour headliners L7, an all-woman band from Los Angeles; the seminal Hollywood punk rockers X. Moving around the Bad Animals control room is Danny Bland, a dark-haired man in jeans, lizard-skin boots, and a cap that says “Willie.” Bland, who helped Jamail line up much of the rock talent, is the manager of the Supersuckers, a red-hot band that moved to Seattle from Arizona a few years ago. Bland grew up in Phoenix, listening to his dad’s outlaw country records. “For four years my band’s been opening their shows with ‘Whiskey River,’ he says. “I told Randall, ‘Are you aware how much these musicians idolize Willie? I bet a lot of them would love to cover him on a record.’ So Randall got me to start asking around. I’d say, ‘The guy has produced Willie and the pope. That good enough?’” Bland chuckles. “This is going to be the first record I’ve ever been involved in that my dad will listen to.”

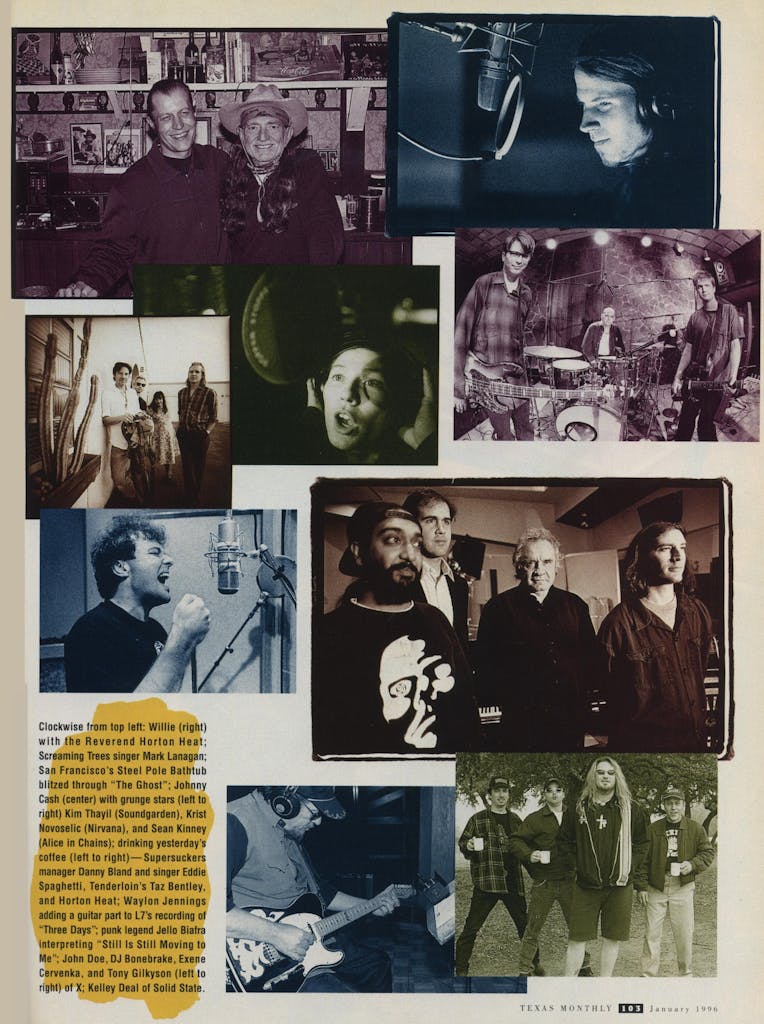

Jamail hopes to tap into the vast audience represented by those platinum records on the studio wall in downtown Seattle, but he wants Willie’s fans to buy the album too. For this session Jamail has recruited a Seattle all-star band to play behind Johnny Cash. “I said, ‘Johnny, I’m doing something kind of perverse with Willie Nelson songs.’ He said, ‘Great, I’m in.’” But Cash won’t show up for several more hours, and he doesn’t know exactly what he’s in for. Jamail, who is a skilled guitarist, has been sitting in with the players, trying to impart his vision of a track from Willie’s 1975 concept album, The Red Headed Stranger. The ominous lyrics of Willie’s “The Time of the Preacher” seem tailor-made for the sonorous drawl of the Man in Black: “It was the time of the preacher/In the year of ‘01/Now the lesson is over/And the killing’s begun.” Over the years Cash has accidentally set a fire in a national forest, holed up in a cave to die, kicked an addiction to painkillers at the Betty Ford Center, and written a novel about the Apostle Paul. Despite the thematic appropriateness, the band finds that turning the song into rock and roll is not all that easy.

The drummer, Sean Kinney, is from Alice in Chains—a Seattle band that ranks only behind Nirvana and Pearl Jam in commercial heft. Kinney is clean-shaven and handsome, with broad shoulders, grungy shirt, and long brown hair. He showed up at the studio with his girlfriend, a sleek and striking model. With each rehearsal, Kinney begins by whacking his drumsticks together four times; as the lead guitar weighs in, he attacks a cymbal like a boxer throwing knockout punches, then sits back with his shoulders squared and nostrils flared. He reaches coolly to the floor at the end of the take and gulps from a bottled beer. “I’m just trying to make it noisier,” Kinney tell me pleasantly in the control room during a break. “Not so candy.”

The drummer seems like a rock star from central casting, but the guitarists are nothing like what I expect. Kim Thayil is the lead guitarist for Soundgarden, a definitive Seattle grunge band that, like many others, enjoyed its first success on a local independent label called Sub-Pop. A dark-skinned young man with lively eyes and black hair and beard, Thayil grew up in Chicago, and his mother was born in India. Struggling with the material, Thayil unplugs his guitar, carries it into the control room, puts on headphones, inserts a CD of The Red Headed Stranger, and with periodic nods and murmurs of revelation, plays along to “The Time of the Preacher,” and finally gets a fair hang of Willie’s flamencolike style. Then he goes back, plugs in, doctors the sound by stepping on an effects box called a chorus, which he has set at full volume, and with yeeks, shrieks, and whongs, turns Willie’s distinctive guitar break into an aural likeness of a train wreck. Everyone agrees it’s getting a whole lot closer.

I am transfixed by Nirvana bass player Krist Novoselic. I’ve read that the defunct Seattle band may have been the most innovative and influential rock group since the Beatles, but the Nirvana lyric that sticks in my mind is “I wish I could eat your cancer.” I am preconditioned by the heroin-addiction and shotgun-suicide lore of bandleader Kurt Cobain, and by a fleeting brush in New York last year with Cobain’s widow, Courtney Love—to my taste, the only thing worse than being around her is hearing her sing. But when Novoselic walked into the studio, if not for the guitar case I would have pegged him for an insurance adjuster. He’s tall and skinny, his thinning black hair is cut short and conservatively, and he wears a white shirt and a blue blazer. During a break he samples some fruit provided by the studio and tells me that he grew up in a small Washington coastal town, the son of Croatian immigrants—a welder-machinist and a beautician. “When Danny Bland asked me if I’d do this, I said, ‘Are you kidding? In a second. Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash? Those guys are heroes of mine.’”

“You really listened to Willie?” I respond skeptically. “Bought his records?”

“Oh, yeah. The Red Headed Stranger was the first one I ever heard. Lotta class, lotta taste. Great songwriting. And Johnny Cash—he recorded ‘The Ballad of Ira Hayes.’ What an incredible song! We were always into these little hot-spot scenes—Minneapolis; Athens, Georgia; Austin, Texas. We listened to a lot of Texas bands. big Boys, Butthole Surfers, the Dicks. If you look at our home video where Kurt gets smashed in the face by a security guard, that was in Dallas. We always had a great time in Texas.” Novoselic says this with an air of such fundamental sweetness that I stare at him and think: Jimmy Stewart. After I thank him for the chat, he lifts his hand and replies, “Sure. Thanks for letting me eat my banana.”

Well into the evening, Johnny Cash comes into the studio with his red-bearded son, John Carter Cash, who will contribute an acoustic guitar track. “Hey, Krist,” Thaymil murmurs to Novoselic as they prepare to meet him. “You know the thing about the nerves? It’s here.” Cash is dressed in his signature black, and his hair looks stiff and tangled, like he just got out of bed. He is disarming and unassuming; he makes a complete circuit of the now-crowded studio, introducing himself to everyone—“Hello, I’m Johnny Cash”—as if any of us might fail to recognize him. This is a face firebombed with experience and character. When the tics start working, you fear he might be having a stroke.

Cash is an old hand at crossover connections with youth; his American Recordings was a career-reviving smash hit with the alternative rock crowd in 1994, and he has recorded with U2. But unlike Nirvana’s Novoselic, Cash was unfamiliar with “The Time of the Preacher,” when Jamail proposed recording it. “I met Willie in about ’56 at a disc jockey’s convention in Nashville,” Cash recalls. “Songwriters came there to meet artists who might record their songs. I’ve always been impressed with him as a musician, but what stuck with me was his writing. We never worked together until the Highwaymen scene came along. I never was that close to Willie.” In the control room he listens to a squalling backup track the Seattle all-stars recorded in rehearsal. “That’s terrific,” he says with a smile, on hearing Kim Thayil’s strange guitar riffs, and they go to work.

Though Cash needs a lyric sheet, he has a sure feel for the torment that drives the song. He records with the grunge rockers for about two hours. “Aw, they had it together before I came in,” he apologizes at one point. Jamail throbs with kinetic energy. “If we get to the point where we don’t recognize the song,” he tells them, “then we accomplished what we set out to do.” But with Cash’s voice and respect for the material, in fact there is little chance of that, and the younger musicians also exercise some restraint. The result is a fusion of a haunting love ballad and the murky and brooding guitar chords that imbue the Seattle sound. And it works. “What we came up with was pretty straight-ahead,” Novoselic tells me afterward. “Randall wanted to do something really weird, but we didn’t have much time. And we didn’t want to embarrass Johnny Cash.”

Jamail was doing well in his talent search before the Cash session, but after that, recording a cut on Twisted Willie becomes a prestige gig. For ascending Seattle-area bands such as Gas Huffer (“I Gotta Get Drunk”) and the Presidents of the United States of America (“Devil in a Sleepin’ Bag”), the album stages them as peers of heavyweights. But even punk rock has its graybeards, and for them the exposure is an authoritative growl from the lair, lest the audience forget. Jamail solicits theatrical contributions from X, best known for the 1980 punk album Los Angeles, and from Jello Biafra, onetime lead singer of the Dead Kennedys, triumphant defendant in a landmark obscenity case, and a surprisingly strong vote-getter in a San Francisco mayoral race. To Willie purists, X on “Home Motel” and Biafra on “Still Is Still Moving to Me” may verge on heresy, but for a producer and president of an obscure independent like Justice Records, both tracks are enormous coups.

Several groups attack Nelson’s material with loud, fond, comic irreverence. Tenderloin, a Kansas band, sets the standard here with “Shotgun Willie.” His lyric “Can’t make a record if you ain’t got nothing to say” is twisted into “Can’t drink a beer if you ain’t got no refrigerator.” But star Seattle singers Mark Lanegan of Screaming Trees and Jerry Cantrell of Alice in Chains balance the uproar with quiet, earnest, almost doleful takes on “She’s Not for You” and “I’ve Seen All This World I Care to See.” The album’s inventive, Beatles-like swing for the fences comes from L7, known as L.A. bad girls and Lollapalooza rivals of Courtney Love. They flabbergasted Jamail when they told him they wanted to revive “Three Days,” an all-but-forgotten love lament that Faron Young recorded before any of them were born. Then they went to a Waylon Jennings concert in Los Angeles with one of their roadies, who is such a fan of the Plainview native that the Waylon song and credo “Lonesome, Ornery, and Mean” is tattooed on his arm. Backstage the gruff Nashville outlaw allowed as how the girls were “real sweet,” inspiring a knowing guffaw from his son, whose nickname is Shooter. And the youth told his dad that he’d be crazy not to contribute a guitar solo and backup vocal tracks to L7’s paean to Willie.

Jennings, who later this year will record a back-to-the-roots Honky Tonk Heroes II album for Jamail and Justice, also contributes a jagged version of “I Never Cared for You” to Twisted Willie. The fourth Highwayman, Kris Kristofferson, lives in Hawaii now and keeps the musical component of his career alive with an approach that emphasizes his visibility as a move actor, his appeal to a largely female audience, and roots in folk rock rather than country. Jamail got him to fly over to Los Angeles for a session with another Lollapalooza headliner, singer Kelly Deal of the Breeders, now with a band called Solid State. The song was “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground,” a Kristofferson favorite, but he walked in to find Deal singing atonally to the accompaniment of the slowed and amplified sound of a sewing machine. She had told Jamail that she was entranced with the rhythm. Descriptions of the hypnotic percussion track vary wildly, but to my ear it sounds like an approach of savage tribesmen beating on sticks.

Jamail describes the scene: “Kris took one look at us and thought, ‘These people are completely out of their minds.’ But he’s a pro. He listened enough to lay down a harmonica track and sing a little piece for the end, then walked out. Then he immediately called Willie. I know he did, because the next day Willie calls me. ‘All right. Tell me about the sewing machine.’”

As Wilie Nelson brews coffee and looks on smiling, Jamail tells this story on a foggy October day in the saloon of an Old West movie set of Austin—part of the Pedernales playground that Willie salvaged from his battle with the Internal Revenue Service (it also includes a golf course and recording studio). Today Jamail is wearing dark blue glasses. He tells another tale of a session with a San Francisco punk band called Steel Pole Bathtub. Jamail suggested a dark ballad called “The Ghost” that Willie wrote in the early sixties. “They start out like they usually do and I say, ‘Wait, wait. You better slow that down. If you play that thing like punk rock, we’re gonna have a fifteen-second song.’”

Willie laughs and says, “Don’t take long to tell a good story.”

For a photo shoot, the honoree of all this youthful attention is decked out in his Red Headed Stranger garb—chaps, boots, and bandanna. He’s also entertaining some of the touring musicians who appear on Jamail’s record. A member of Tenderloin nervously asks him to autograph a dollar bill for a friend. On a stool next to me is Eddie Spaghetti, the lead singer of the Supersuckers. He has a cap, an earring, a stubble growth of beard, and a friendly round face. My 22-year-old stepdaughter, who is my primary guide to the alternative rock scene, has told me with a laugh that he is a heartthrob: “I’ve got a friend who wants to marry him. She says, ‘I want my name to be Megan Spaghetti.’” The Supersuckers recorded their version of “Bloody Mary Morning” in Austin’s Arlyn studio, and Willie contributed a cameo guitar solo, impressing the youths with his ability to play that fast. I ask Spaghetti when he connected with Willie’s music, and he says it was after high school, when the band was chasing gigs and learning the ropes in Arizona. He smiles and grips an imaginary steering wheel: “It’s road music. Put that in and just groove.”

The one I really want to meet is the Reverend Horton Heat. His real name is Jim Heath, and he grew up in Dallas, San Antonio, and Corpus Christi; he dropped out of college in Austin, then surfaced in Dallas’ Deep Ellum warehouse scene in the mid-eighties. My stepdaughter has been telling me for years that his music is rockabilly as much as anything. She also mentioned one night, “He plays the guitar with, uh, his penis.”

“Jesus! Doesn’t that hurt?”

This is not the kind of conversation we’re used to having. “I don’t know,” she said, blushing. “I mean, he’s wearing jeans.” (In fact, the musician grinds the neck of his guitar with his pelvis, producing a psychedelic sound.)

The Reverend Horton Heat is in his mid-thirties with slicked-back blond hair, long sideburns, and a toothy, wolfish grin. For my money, despite the merits and guaranteed hype of the Johnny Cash and L7 productions, the only Texan in Jamail’s alternative lineup delivers the album’s blow-away success. Heat’s baritone voice may not have great range, but with a driving guitar solo and brief vocal duet with Willie—the only one on the record—he shows that the career-spawning country and western classic “Hello Walls” is a great rock and roll song. One more time, it deserves to be a number one hit. “Since it swings, I thought we could make it swing a little harder,” says the Dallas rocker. Heat leans against the movie set’s likeness of an outhouse, smoking a cigarette. “The outlaw business is a cliché now,” he reflects, “but for a guy to get kicked around as hard as Willie was in Nashville and then come back and make it all happen here—Texas individualism is what it is. That guy’s the king.”

The youths drive off in the fog, and I linger awhile with Willie. In March sixteen alternative rock bands and all four Highwaymen are going to celebrate their strange record with a wild concert at the Universal Amphitheater in Los Angeles. The rockers are already promoting the album in their road shows. I ask Willie if he was familiar with the musicians Jamail brought to his royalty statements. “I heard the names,” he replies carefully. “I was surprised that there was that much knowledge among younger bands of my old songs. Some of the cuts they picked up on are really obscure.”

By commercial measure Willie’s career has been in decline for several years. His last number one record was “Nothing I Can Do About It Now” in 1989. After investing heavily in his 1993 album Across the Borderline and his sixtieth birthday celebration the same year, Columbia, his longtime record label, let his contract lapse. At 62 the singer finds himself shopping for labels and recording for an unevenly distributed independent like Justice, and mainstream country and western radio is deaf to his music; according to Jamail’s market research, Willie’s records get airplay mostly on roots rock stations and on country stations in towns of fewer than 200,000.

Yet it would be hard to find an artist with less concern. He goes on pleasing and replenishing his audience with his road shows, making the records he wants to make, and finding someone who’s eager to bring them out. All the rest is just gravy. His credo: “Fortunately, we are not in control.” In L.A. renowned producer Don Was is working with Jamaican musicians on another record drawn entirely from his material—reggae cum Willie. As for the adulation of these punk and grunge rockers, who knows? The embrace of alternative rock might propel him to a big commercial comeback, as it did Johnny Cash. But whatever happens, he can’t help but love Twisted Willie. He has been a great songwriter, but he has also been a superb interpreter. With all respect for the original context, Willie has imparted his own twist on the work of Hoagy Carmichael, Irving Berlin, Bob Wills, and Ira Gershwin. Interpretation is how music goes on living.

I tell him about watching the Soundgarden guitarist Kim Thayil play his buzzing guitar accompaniment to “The Time of the Preacher” during the Seattle session, and Willie flashes a smile of great pleasure. “Did you hear what Johnny said about Kim’s using the chorus?” Willie asks. I shake my head. “Cash called me up and said he had asked Kim that night, ‘What’s the purpose of the guitar chorus?’ ‘The purpose,’ Kim said, ‘is to destroy the melody.’ Cash said, ‘Fantastic. Now I understand.’”

- More About:

- Music

- Longreads

- Country Music

- Willie Nelson