This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

For going on twenty years Austin City Limits has been the elite soundstage of American popular music. The glitzless public television program, which is produced at station KLRU on the University of Texas campus, began and still fashions itself as a window into Austin’s celebrated barroom scene, but over the years an array of performers have trooped into the studio and played for union scale, including Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, Chet Atkins, Ry Cooder, Flaco Jimenez, Ray Charles, Leo Kottke, Pete Fountain, Loretta Lynn, B. B. King, Bonnie Raitt, Jerry Lee Lewis, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Fats Domino, George Jones, George Strait, George Thorogood, Waylon Jennings, Garth Brooks, Leonard Cohen, Emmylou Harris, Little Feat, Los Lobos, Robert Cray, Doug Sahm, Freddy Fender, Lyle Lovett, Dr. John, Johnny Cash, k. d. lang, Joan Baez, and Taj Mahal. The list is stunning.

Musicians love the show because they don’t feel smothered by the medium of television. The technicians—many of whom have been together for fifteen years—pay attention to sound quality and stay out of the way. Within the industry their approach has been copied frequently, most recently by MTV’s vastly successful Unplugged series. Every week, not counting reruns and overseas broadcasts, Austin City Limits reaches an audience of nearly two million in the U.S. No other artistic medium that is truly Texan in origin comes close to matching its imprint on American culture. Of course, any season could be the last. The Public Broadcasting System (PBS) is a beleaguered mom with an elitist reputation in Congress and a steadily shrinking purse. The show scrapes by with underwriting grants: $125,000 from the Frito-Lay corporation, $50,000 from the City of Austin. And so far, negotiations with entertainment companies have failed to yield the CDs and videocassettes that would generate new revenue.

Still, Austin City Limits perseveres. Country music is in the throes of an identity crisis—it doesn’t know what it’s supposed to be anymore, so it tries to be all things to all people—and that works to the program’s advantage. The loosened corset enables it to reach far beyond the music played on country radio stations, which enlarges the show’s audience and upgrades the quality of its playlist: Nashville’s contradictions are remade into Southwestern eclecticism. And in the strangest twist, though Nashville smashed Austin’s cocky little insurrection of the seventies, the C&W industry has honed its product and pushed it around until it almost echoes the Texas sound that was branded “outlaw” in Nashville twenty years ago.

One afternoon last September, at the rehearsal for the season opener, the paradoxes were hard to miss. The stars drifted into the studio sporting pricey athletic and hiking shoes, well-groomed beards, and collar-length hair, not a cowboy boot or gleam of hair oil among them. Their leader, Vince Gill, wore cutoff jeans, a T-shirt, and in that ubiquitous fashion statement of the times, a baseball cap turned around on his head. (They would change into their dance hall attire at show time.) Gill is the reigning king of Nashville country music. Ten days later, he would be voted entertainer of the year and top male vocalist by the Country Music Association, and he had a song on the number one album, Common Thread, an anthology of tributes to the seventies rock band the Eagles. To purists and cranks, such a record exemplifies everything that is wrong with country music in the nineties. Merle Haggard, who feels that he has been put out by the industry on an ice floe and is none too serene about it, gripes that it all sounds “like rock and roll strained through milk toast.” But Nashville has long been the Ellis Island of American pop: Give us your dispossessed, your possible crossovers, your slightly out-of-fashion. Gill, like other country stars, has commandeered a durable and engaging sound that is relegated elsewhere in the market to nostalgia tours and oldies radio.

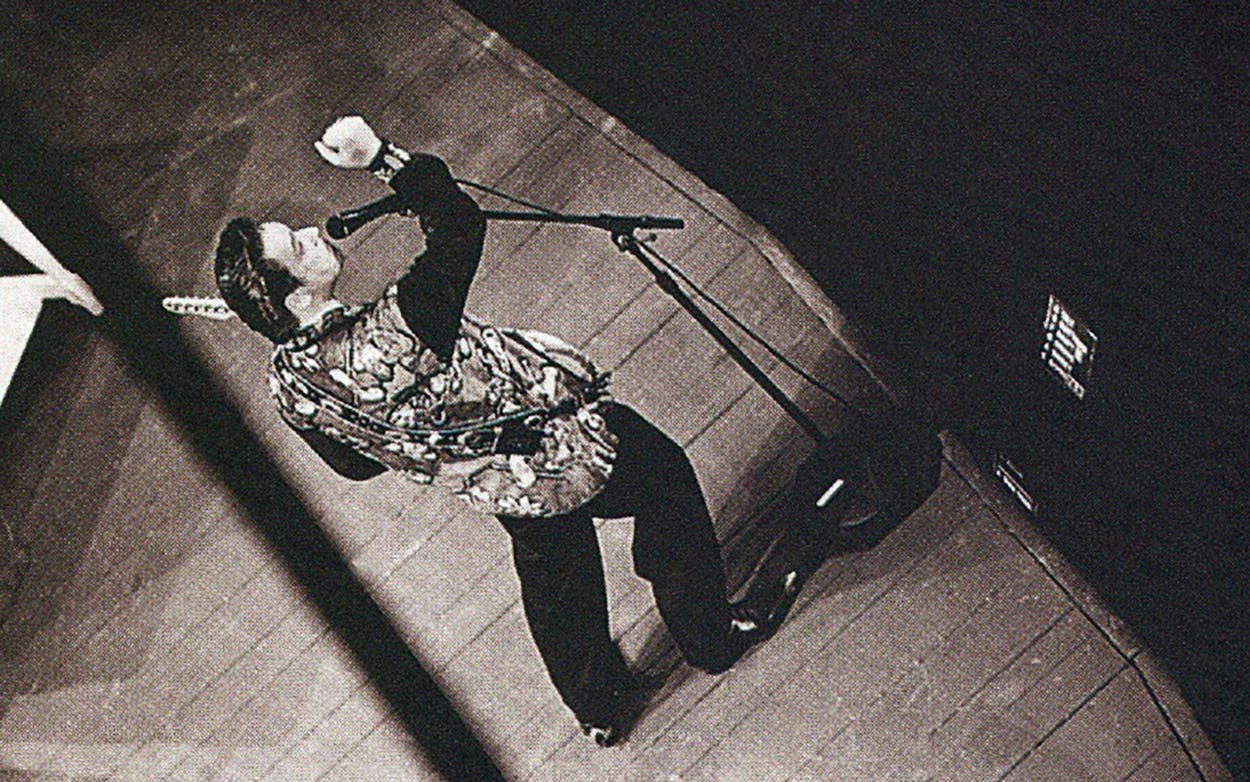

And there’s nothing devious about it. Gill first appeared on Austin City Limits in 1979 as a long-haired guitarist and singer with Pure Prairie League, a Southern country-rock band that sounded like the Eagles. The signatures of the descendant style that dominates mainstream country music today are a big, pretty, far-reaching tenor and a load of instrumentation and backup vocals: love songs and laments, nothing too hokey, framed by numbers short, loud, and danceable. Gill has a ten-piece band and is a splendid lead electric guitarist; rock stylist Mark Knopfler once asked him to play with Dire Straits. At the taping Gill dropped the name of Delbert McClinton, a Fort Worth roadhouse blues veteran and program favorite who had written a hot new song with him in Nashville. Gill called Austin City Limits “the hippest show on television” and for his encore sang a few smooth bars of the show’s theme, “London Homesick Blues.” Gill defines the genre: He’s tall and good-looking, and there’s not a rough edge on his face—or in his music.

By contrast, Junior Brown fretted and sweated through his rehearsal and performance backed up by his wife, Tanya Rae, on acoustic guitar; an expressionless, gum-chewing drummer; and a policeman’s son on stand-up bass. Brown is a baritone, not a tenor, and he plays an instrument he calls a guit-steel—a combination electric and steel guitar on a wooden frame, which he props on a stand behind his singer’s mike. On this day Brown wore a straw hat; he looked like Don Knotts as Mayberry deputy Barney Fife. The music business has a term of condescension for country artists who wear hats—“hat acts.” Hat acts often create problems for Austin City Limits technicians because the brims cloak the artists’ eyes in deep shadow. At the rehearsal Brown advised an associate producer of another hazard: “When I lean over to play a solo, my hat will sometimes make a feedback.”

Not long ago Brown was a community college teacher in Oklahoma. Today his weekly gigs pack Austin’s Continental Club with devotees who have nose rings and inked-up arms—the alternative crowd. Brown’s songwriting is built on humor. In one song he croons, “I got to get up every morning just to say good night to you.” In another, he tells why an old flame should not be rekindled: “ ’Cause you’re wanted by the po-lice and my wife thinks you’re dead.” He has a mimic’s ear, but there’s no putdown in his delivery. Merle Haggard contemplates the plight of the homeless, and George Jones and Ray Price are crying in their beers; the Grand Ole Opry cautiously allowed Brown onstage to sing his “My Baby Don’t Dance to Nothing But Ernest Tubb.” In a trucker’s song he drops a Roger Miller lyric into the revved-up growl and guitar run of Dave Dudley: “I’m the king of the road, she’s the queen of the house, and it may not be a palace / But it sure beats a load by the side of the road, broke down south of Dallas.” Brown’s routine drew raves in the New Yorker as “country music for people who hate country music.” You figure it; his take on older and rawer styles of country and western is almost reverential.

Nowadays, people who get tickets to an Austin City Limits taping are largely corporate sponsors of the program and contributors to KLRU and the university. Not the youngest and hippest music crowd in town. Most had heard of the superstar Gill, who entertained them well, but one could see them gasping when Brown came on afterward and stole the show. It was no surprise to the cultists who managed to slip inside, nor to the program crew, who seated them up front, where the cameras couldn’t miss them. One fellow with a crew cut, T-shirt, and bib overalls stood up after every song and wagged his finger slyly at his hero’s nose.

Brown closed out the night stooped over his strange guitar. Sucking on his cheeks, he used Hank Garland’s “Sugarfoot Rag,” an instrumental that helped define the Nashville Sound, as a springboard into a reprise of a flaming, acid-rock solo by Jimi Hendrix. Hours earlier, at rehearsal, Vince Gill and his band mates had watched Brown play the same song. When a sideman murmured a gibe in Gill’s ear, Gill rolled his eyes and said, “ ’Scuse me, while I kiss the sky.” The line, of course, was an echo of Hendrix, not the Grand Ole Opry.

Austin City Limits began with a burst of UT construction rather than creative inspiration. A building surge engineered two decades ago by regents chairman Frank Erwin transformed the campus’ public TV outlet—then part of an Austin–San Antonio co-op called KLRN—from a hole-in-the-wall into a full-blown station with studios and equipment. The program director at the time, Bill Arhos, a burly mustachioed man of Greek ancestry and a former star pitcher for the Rice Owls, took one look at the sudden wealth of technology and started searching for a program concept he could pitch to PBS. “What is the most visible cultural product of Austin?” he recalls thinking. “It was obvious. It’d be like ignoring a rhinoceros in your bathtub.”

Back then, progressive country was a fusion of country and western, rock and roll, folk, blues, and gospel. The Armadillo World Headquarters was its best-known venue, and its biggest stars were Willie Nelson, Jerry Jeff Walker, and Michael Martin Murphey, who coined the other collective term, “cosmic cowboys.” Its commerce was clouded by hippie credo, but the club scene was as hot as a bacon skillet. Arhos enlisted as his talent consultant Joe Gracey, an FM disc jockey who packaged the local favorites’ few records with those of Southern rock bands like the Allman Brothers and departed Texas saints like Bob Wills and Buddy Holly. PBS member stations liked a fundraising pilot, which starred Willie Nelson, enough to include the series in the 1976 season. The early tapings had none of the polish of the productions today. Heads and shoulders rose up in front of the cameras, which moved around in clumsy view. One of the biggest problems was drawing a crowd. “We were begging people to come in off the street,” Arhos says. “My favorite was a guy who’d been sniffing paint. You could see it on his moustache: silver. He had a terrific time.” When artists forgot a line or hit a bad note, they kept going—they were bar musicians. The Lost Gonzo Band launched one show with a song about dead armadillos; their leader, Jerry Jeff Walker, slouched onstage with his shirttail out. He looked up at one point and grinned at somebody dancing in a gorilla suit.

The program survived because it was genuine and different; the only rival country music show on the air was the cornball Hee Haw. Gracey lured the late Bob Wills’s band, the Texas Playboys, out of elderly retirement for a classic pairing with their Western-swing descendants, Asleep at the Wheel. PBS programmers rose up aghast, though, against the first-season offering of Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys. Friedman either sensed he was moving off into his new trade as a mystery novelist or was dreadfully naive about what would fly. Whatever the case, public TV wasn’t ready for a Lenny Bruce with sapphire sunshades and a matching fake-fur guitar strap. Arhos offered subscribers a tape of the hilarious show as a bonus, but it never aired anywhere. A few copies of the satire live on as an underground collector’s item.

While the cosmic cowboys were riding herd in Austin, Terry Lickona had been working as a rock deejay at an FM station in Poughkeepsie, New York. When the station’s management ordered a switch to a country and western format, they let him keep his job and play whatever he could stand to listen to. “Callers kept telling me I ought to go down to Austin, where there was actually a music scene close to what I was playing,” Lickona says. “So I did.” After moving in 1974, Lickona was disappointed in his hopes of bowling over Austin radio and took a public-affairs job at KLRN (the forerunner of KLRU); in 1979 he became Austin City Limits’ full-time producer. Ever since, Arhos (now the president and general manager) has been the country and western devotee who negotiates the minefields of PBS, while Lickona has booked the talent and pushed the creative envelope. “Bill’s the one who says no,” one crewman says, describing the relationship.

During Lickona’s first season, his adventurism peaked with the throwback beatnik Tom Waits, known these days more for his acting than for his gravel-voiced singing, and for good reason. (“I still don’t know how he got on there,” Arhos grumbles today.) With great billows of cigarette smoke, Waits lounged in red and blue light between two antique gasoline pumps, a spare tire slung over his arm, and rambled on for ten minutes in Kerouac fashion about Burma Shave and alienated youth: “He was just a juvenile delinquent / He never learned how to behave.” It finally became apparent this was a prelude to his singing “Summertime.”

Artists’ use of tobacco, highly visible in the early years, vanished when the university instituted its no-smoking policy. A more telling disappearance was the music scene that spawned the show. The progressive country FM radio format died first. In 1980 the Armadillo closed, and suddenly it was over; Willie Nelson’s national stardom and Asleep at the Wheel’s Grammy award were the only traces left. All at once the club rage in Austin was disco. When a PBS programmer flew down to see this hotbed of creativity, Arhos drove her all over town, mortified, in search of one country band.

Austin’s live music scene resurfaced quickly, but in the form of punk rock—a long jump for subscribers who thought they had been sold a country music show. The admirable course would have been to follow the Austin scene wherever the changing styles and emphases of Texas music took it, but there is little doubt that PBS would have gotten dizzy and ceased to renew the show. Starting in 1980, for every Joe Ely or Joe “King” Carrasco, there were ten productions of Don Williams, Roy Clark, Tammy Wynette, or Larry Gatlin. Complaints arose that the producers ought to rename the show Nashville City Limits. But they really had nowhere else to go.

During those years legendary musicians of national stature (Ray Charles, Jerry Lee Lewis, Neil Young, Emmylou Harris) began to arrange their tours so they could swing by Austin and do the show, and they felt no need to stick to country. A 1983 highlight was the emergence from long seclusion by the West Texas rockabilly Roy Orbison, who wore black clothes, white loafers, the world’s worst hairpiece, and the thick smoky glasses of the almost-blind. Orbison was clearly in poor health, but he hadn’t lost a note of his soaring register. The producers were much slower to embrace the driving force of the Austin club scene in the eighties: rhythm and blues. When Stevie Ray Vaughan finally got on in 1984, he played so loudly that ceiling insulation drifted down like snow. By his next appearance, broadcast a few months before his death in 1990, he had grown into his voice and stage presence. Beads of sweat dripped off his chin and ran down the guitar’s face. In the edit another production might have shied away from the tearlike effect. But Vaughan was a virtuoso, and watching how he made an electric guitar do all that was spellbinding.

In 1993 Lyle Lovett walked out in a brown gabardine suit with his “large band” and a quartet of black gospel singers. He said he felt like he’d grown up on Austin City Limits, and by then it was evident that this homely young man was no geek; he deserved the superstardom breaking around his head. He showed the comic instinct that caught the eye of film director Robert Altman, and perhaps some presentiment of his own. “I’d like to make a special dedication,” he said with droll pauses and nervous cuts of his eyes, “to anyone in the audience who’s ever been involved in a romantic relationship of any kind . . . and, and, who may have had the relationship not work out quite the way you had hoped it would . . . and, and, who may have consoled himself or herself by rationalizing that the person who maybe initiated the breakup will one day . . . live to regret it.” The name of the song was “She’s Leaving Me Because She Really Wants To.” Country music, yes. But like Willie Nelson, who on the same stage taped the pilot that first caught the executives’ eyes, Lovett’s inventions and phrasings are those of a jazz singer.

Rap, hip-hop, and heavy metal will probably never make it onto Austin City Limits, but within the boundaries of the show’s original definition, it’s hard to look down the anthology of past performers and Lickona’s list of prospects and think of a deserving Texas recording artist the program has missed or ignored. The twentieth-anniversary lineup taps into the Beaumont scene—hat-act country, with a dash of cajun spice—and Freddy Fender hosts a special of tejano performers who are making San Antonio the state’s hottest music town. Guitarist Jimmie Vaughan, like his brother, Stevie Ray, did years ago, steps out front and tries to make his voice work as well as his hands. Shawn Colvin, who has said she is much indebted to the songwriting of Tom Waits, celebrates her recent move to Austin. The anniversary season even unearths a cosmic cowboy of the nineties: Robert Earl Keen. In the last days of the Armadillo, he and Lyle Lovett were friends, rivals, and classmates in College Station. Once more, it’s the Aggies who keep tradition’s flame alive.

The hostility to Nashville that pervaded the Austin music scene in those years seems like a pointless conceit today. The new season’s most exciting country band hails from neither town: The Mavericks are from Miami, and their lead singer, Raul Malo, is an auburn-haired Cuban who sounds like he grew up with headphones and a stack of Sun records from Memphis. It struck me, as I watched a classic show by New Orleans’ Neville Brothers, that only in this studio in the fall of 1994 could one find a crowd of white middle-aged Texans howling and dancing to a song about the dignity of the people of Haiti. Austin City Limits outgrew its parochialism long ago.

Arhos’ proposal for a twenty-first season noted that the show leads public television in attracting viewers with a high school education or less; half of its audience earn less than $20,000 a year. “We’re the bone that PBS throws that dog,” one crew veteran told me with a fatalistic grin. It’s an article of faith among the crew that the typical viewer is now a Southern white woman in her fifties. Maybe so. But her taste is broad and curious, and she can still rock and roll.

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Country Music

- Austin City Limits

- Austin