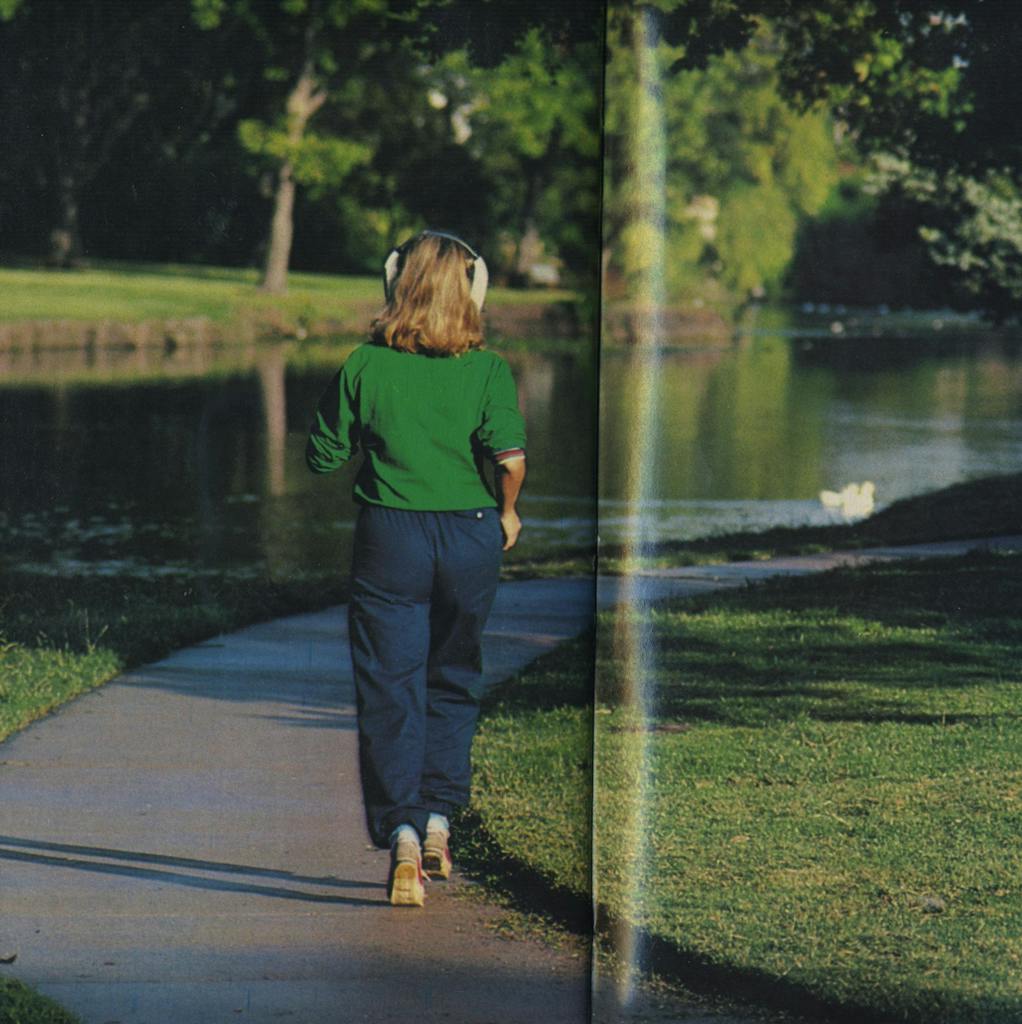

Now that the maid had arrived and was busy preparing breakfast for the kids, Ann pulled on her running clothes and stepped outside for her two-mile jog through the neighborhood. Her street showed few signs of life this early: a barking dog, a small nightgowned child sleepily sitting on her sidewalk steps cradling a cat, an elderly man picking up the morning newspaper. As always, nothing appeared to be amiss along the streets of Highland Park—the still-slumbering neighborhood seemed to have existed forever. Constancy and predictability were two of its greatest glories; surprise was as rare as rubbish or decay. There was little to startle a stranger except perhaps the sudden activation of a lawn sprinkler system. As Ann began her run, carrying a cloth napkin to wipe away the sweat, the morning silence was interrupted only by the hum of air conditioning units dispensing comfort and cold air and by the periodic roar of jet aircraft overhead.

Ann lives near Normandy Street, between the Dallas Country Club and the Arch McCulloch Middle School, in a house neither mansion nor bungalow—two stories, four bedrooms, den, swimming pool. Bought five years ago for $95,000, the house is now worth at least $300,000. Ann is 34, recently divorced, the mother of Tommy, 9, a fourth-grader at John Armstrong Elementary School, and Shana, 15, a freshman at Highland Park High School. Ann has a tweedy, cared-for look common to women in affluent suburbs. Her hair is a sun-streaked blonde, and she often ties it back on her neck with a ribbon. She has deeply tanned skin, crinkly squint lines around her eyes, a good, healthy body. She usually wears two small diamond earrings, a lady’s Rolex watch, oversized sunglasses, and her grandmother’s ring. Her clothes reveal a careful sense of style, subdued yet fashionable, cautiously au courant. Whether it’s fashion, children, interior decor, money, or conversation, Ann always knows the difference between discreet good taste and vulgar excess.

She crossed Mockingbird Lane and jogged south beside the country club that sits in the middle of Highland Park. On the streets near the fairways, crowded with the green of overhanging branches, lights began to appear in the windows of the older prairie-style houses with wide wraparound porches and the brick mansions sitting behind thick, manicured lawns along Beverly Drive. South of the country club, Ann continued along Lakeside Drive, the town’s most prestigious street, and watched the ducks gliding on Exall Lake and resting on the grounds of the estates that line Preston Road to the west. It was a sylvan, bucolic scene reminiscent of Wordsworth’s English Lake District, but it existed right in the middle of the state’s second-largest urban area.

Highland Park is an island just north of downtown Dallas, a small town of 8800 people dedicated to preserving the stable, traditional values of an earlier America. Those values don’t come cheap.

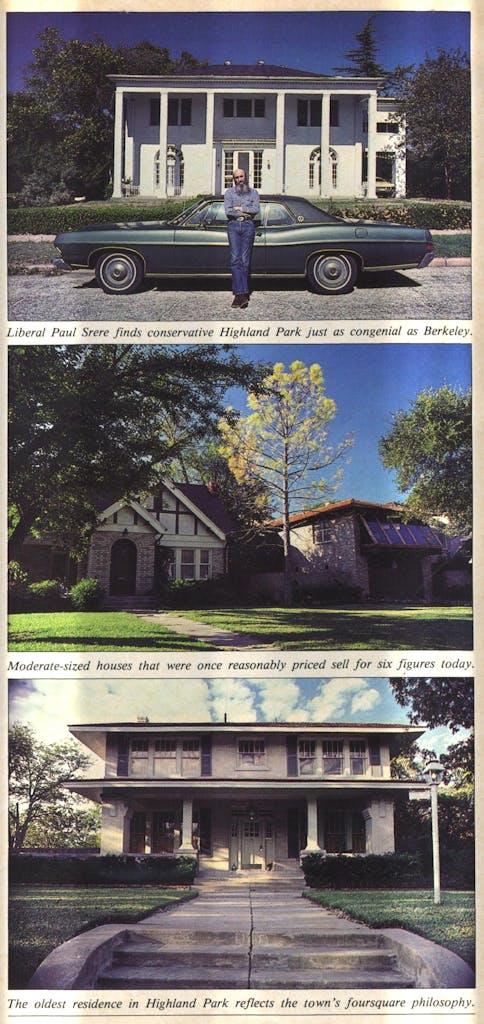

Highland Park is an island just north of downtown Dallas, a small town of 8800 people dedicated to preserving the stable, traditional values of an earlier America. Those values don’t come cheap. Unlike Houston’s River Oaks and other wealthy neighborhoods, Highland Park is actually a town. Not all of its homes are huge and imposing. On the east side, near the Central Expressway, are smaller “two-ones” (two bedrooms, one bath), bungalows where a decade ago a young lawyer or junior executive could have afforded to live. But that particular dream is no longer so accessible. The bungalows go for $150,000 and up, which means that only the wealthy can afford Highland Park now.

By the time Ann returned home the pulse of the street had quickened, as if it had heaved a lethargic sigh and gone to work. Neatly coiffed middle-aged men with purposeful strides and brushed coats left the spacious houses bound for their offices. Women like Ann would leave and return to their homes on many different missions, beginning with herding children into cars, Ann’s first task in a long day of activities. After the school car pool, she had her thrice-weekly exercise class; a Junior League meeting; an appointment with Jim Smith, the family counselor, at Highland Park Presbyterian Church; Tommy’s soccer practice; a drink with her ex-husband, Jack, to discuss the division of the marital assets; and a trip with the kids to Los Vaqueros in the Highland Park Village for a Mexican food supper. She had purposely left the noon hour open.

Dressed in her exercise leotard and ballet shoes, Ann began collecting neighborhood children. Tommy sat in the front seat with his notebook and Star Wars lunch box, relating an interminable tale about some television show, mimicking the voices of the different characters. Shana sat in the back, staring out the window, quiet and moody, occasionally firing statements at her mother about why she should get a hardship license so she could drive at fifteen. Soon the car was heavy with handsome youngsters whom Ann dropped off at school.

Just before nine, women in leotards, shorts, T-shirts, ballet shoes, and running shoes hurried from the parking lot across the street from the Highland Park Athletic Club to the exercise room on the club’s second floor, next to the five racquetball courts. Ann recognized several of the Mercedes outside and, as always, admired the blue rag-top Rolls-Royce that reminded her of when cars were worth looking at.

The leader of the exercise class, Jenny Ferguson, is an old Highland Park girl who used to sell real estate and now has the most popular—especially with the younger women—of the three Highland Park-area fitness groups. B. J. Norris’s class attracts a slightly older crowd, while the town’s grande dames still twist and stretch with exerciser emeritus Louise Williams. All three accompany the exercises with music.

Sometimes it seems that the entire ambulatory population of Highland Park is running and puffing and bending in an almost comic narcissistic urge to keep fit.

Sometimes it seems that the entire ambulatory population of Highland Park is running and puffing and bending in an almost comic narcissistic urge to keep fit. Normally healthy women trade war tales of jogging bruises and muscle failures at their luncheons. Wisecracks persist about being trampled by the gallopers at Park A, the town’s $60,000 jogging track and soccer field. And here at the HP Athletic Club, 35 women (including 2 who were actually overweight) bent elbow to knee and exhaled with a “choo” sound to a Blondie record while Ferguson, her black hair pulled into a ponytail, urged her charges to bend lower and finally to “kick it out.”

Ferguson, sleek and firm in a black leotard, stopped only to change records. It was a diligent and rigorous session, but very few of the women dropped out. “One or two more?” asked Ferguson. “Two,” the class wheezed back, anxious to work to the limit. Finally it was almost over. As Boz Scaggs sang “Look What You’ve Done to Me” the class sat in a yoga position, breathing deeply, swaying and sweating, achieving an almost meditative mood that was enhanced by the romantic ballad. Afterward, Ann and her friends swapped racy gossip, opinions on the Armstrong School teachers, and information on maids, sales on Ralph Lauren Polo shirts, and the latest inflated price paid for a Highland Park house.

A Sigh in the Supermarket

By midmorning Highland Park is a no-man’s-land, a town given over to women and babies. The men who remain—police officers, yardmen, carpenters—are insignificant compared to the numbers of visible women. As downtown has always been the male bastion, so the suburb has always been a female world, created from the beginning for raising children away from the turmoil of the inner city. Parenting is the only industry in Highland Park, and its assembly line workers, supervisors, and president have always been women. The job of Highland Park men is to leave town each day and earn enough money to keep the industry solvent. Ann thought of this after the exercise class when she stopped at the Village Safeway, filled at any time of the day with many of her women friends, constantly exchanging hey-hah-yews. She had avoided this intimate store for weeks and now she knew why. At the sight of the familiar, carefully made-up faces a slight depression came over her like fog drifting inland. Sometimes she felt she had spent her whole life in Zip Code 75205, Highland Park, Texas.

Back home Ann rested on the pool patio and absentmindedly examined seashells from last summer’s trip to South Padre Island, brought home to bleach and fade like photographs left in the sun. Her depression intensified as she realized how much housework she had to do at noon. With Jack gone, her house had suddenly grown huge and unwieldy despite the maid’s and her own continuous work to keep things in order. This house possessed her, she did not possess it. Walking inside, Ann sat down in her living room, a misnomer if there ever was one. Where was the homely litter that proclaimed that family activity had occurred here? She couldn’t think of anybody she knew who “lived” in their living rooms. Their rooms were all cold and empty of life, like department store windows that were roped off and used only as advertisements for symbols of success—the best furniture, a grand piano, valuable paintings, an expensive antique.

But only the living room seemed superfluous. Although Ann knew her house was too big, she had grown used to it, felt proud of the status it gave her. In Highland Park status is not determined by generational ties of locality or kinship. It is an unwritten rule of this province that people are judged largely by the number of things they own. People who are honest with themselves understand this perfectly, and so it was painful for Ann to think of stepping down in the Highland Park world to a duplex or a smaller home. But she knew she had to move soon and then, after getting settled, to find a job.

She would begin the search for a house by seeking out real estate agent friends, like Janet Caudle and Martha Tiner, who knew the territory. And she would also talk to them about what their jobs were like. She realized that knowing how to wash dirty laundry rated higher in the marketplace than her UT degree in history. Despite her Safeway-induced depression, Ann knew one thing: that she didn’t want to leave Highland Park, that her silent vow to settle elsewhere was a vain formality. Now that she was there she wasn’t going to leave. This beautiful, safe town of tree-shaded streets and good schools, free of pollution and racial strife, was the American dream come true—a material heaven in the here and now. It was the intent of its founders for their town to represent not what the world was like but what people said it should be.

Attracting the Best

Ever since immigration and industrialization changed the character of American cities in the nineteenth century, persons of means have pushed outward from the blighted, overcrowded areas to what are now known as the suburbs. In 1860 Boston’s horse-drawn trains moved a total of 13 million passengers—New York’s many more—back and forth from homes on the city’s outskirts to jobs downtown. In the latter part of the century transportation innovations like the trolley made it possible for the clerk and the middle manager to join their boss in the move away from downtown, leaving only the poor behind. While the earlier rush to the cities from the country had had an economic objective—to make money—the movement to the suburbs was explained in sociological terms—“It’s better for the children.”

The post-World War II era witnessed what might be called the greatest land rush in our history—to suburbia. It was caused by boom times: universal car ownership, an expanding highway system, more babies, new mass production techniques pioneered by builders like Bill Levitt of Pennsylvania, who created low-cost suburbs on large tracts of land. Between 1960 and 1970 the nation’s population increased by 13 per cent, to about 205 million. Seventy-three per cent of this growth occurred in the suburbs. In 1950 the population of Irving, a suburb of Dallas, was 2621; in 1960, 45,985; in 1980, an estimated 120,000.

One third of all Americans live in suburbs. Suburbs differ in many ways: house prices, income level, occupational makeup, educational level, religious and ethnic character. The major characteristic of the suburbanization of America, however, has been to further the division of Americans into a two-class society—one affluent, the other poor.

Land developers have always known that people, especially the wealthy, prefer to live near others as much like themselves as possible. Most of New York City’s well-to-do live in only one of the city’s 315 square miles—between 65th and 78th streets, east of Central Park from Fifth Avenue to Third Avenue. The same is true of many Texas cities: River Oaks and Memorial in Houston, Alamo Heights in San Antonio, Westover Hills in Fort Worth. There are those to whom place is unimportant, but to the inhabitants of communities like Highland Park location is everything.

The name itself suggests a natural, serene community, distant but not withdrawn. The site chosen in 1906 was in fact 130 feet higher than downtown Dallas, four miles to the south. Turtle and Hackberry creeks ran through the land, and due south of the acreage was the Dallas Golf and Country Club. From the beginning John S. Armstrong and his two sons-in-law, Edgar Flippen and Hugh Prather, Sr., planned for at least 20 per cent of the original 1300 acres to be set aside for parks and what are now called greenbelts.

The new community was a natural extension of the mansions creeping north along Turtle Creek from Reverchon Park. It was advertised as “beyond the city’s smoke and dust.” The Dallas Morning News retaliated by running the slogan “It’s ten degrees cooler in Highland Park” on the front page during bitter winter weather. The old trail that ran from Fort Preston, on the Red River, to Austin became Preston Road, the town’s first paved street. It also divided the stark cotton fields to the west from the tree-lined creeks and lakes on the east. Since then the area east of Preston Road has always been more desirable than Highland Park West.

To plat their town Flippen, Prather, and Armstrong imported one of the country’s finest landscape architects, William David Cook, who was also responsible for planning an elite California community named Beverly Hills. In 1907 they sold the first lots east of Preston Road in Old Highland Park. Then, in November 1913, after the City of Dallas had refused to annex the growing suburb, the citizens of Highland Park voted 47-7 to incorporate. One of the town’s first laws prohibited the “running loose of cattle, horses, and chickens.”

Several years later Prather wrote in Golf Illustrated magazine: “I have no hesitancy in saying that the Dallas Country Club has by far been the greatest influence in bringing into our residential development the very best element of Dallas-North Texas.” The Dallas Golf and Country Club, Texas’ oldest, had been located south of the city on Turtle Creek, near the present intersection of Oak Lawn and Lemmon. It had a six-hole course and used tin cans for cups. The Flippen-Prather Company persuaded the club to buy 150 acres (for $35,000) in the middle of their town, along its most important streets and creeks. The new club proved an irresistible lure for “the very best element.” Before Highland Park land was even officially on the market, 172 of 186 lots had sold for more than $430,000, the largest suburban land transaction in Texas history up to that time.

Son of the Founding Father

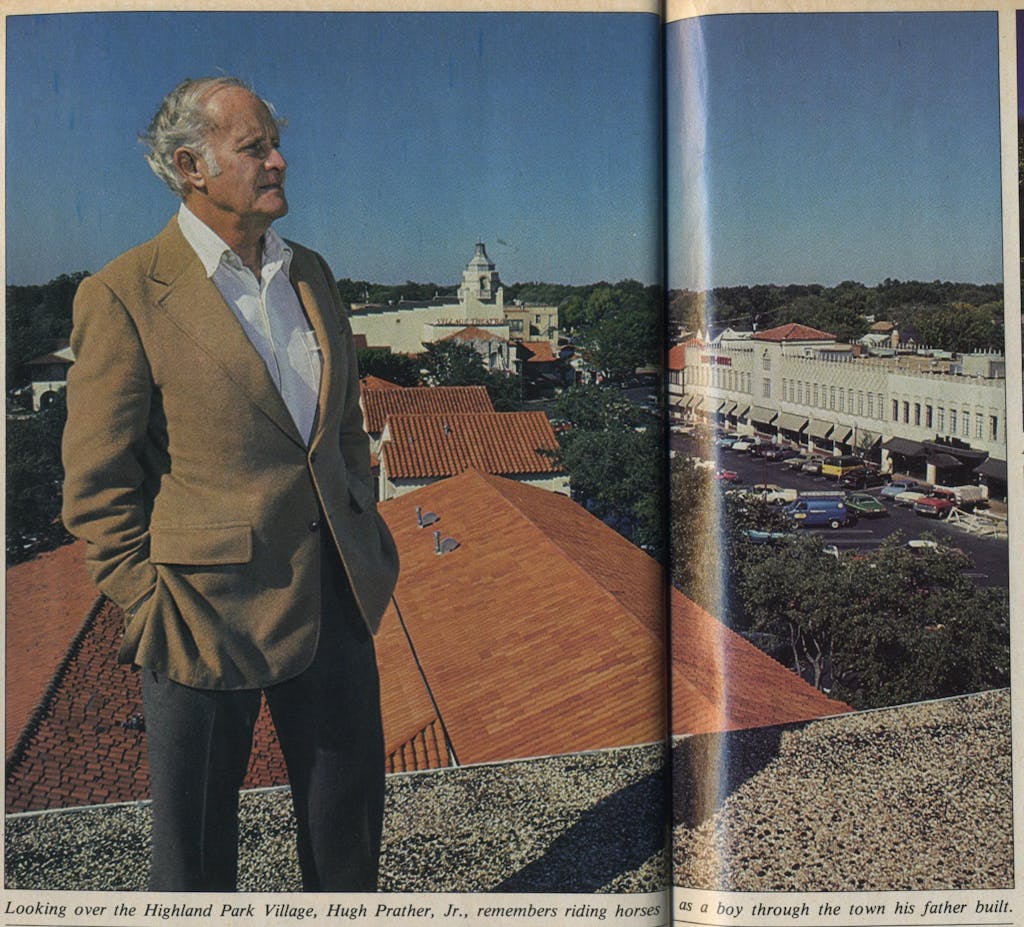

Recently Hugh Prather, Jr., stopped his car along Lakeside Drive near Armstrong Avenue and walked toward the spring where his great-grandfather, William T. Edmondson, had watered the team that brought the family from Tennessee back in the early 1850s. Prather’s grandfather had four sons and a daughter. Ed, the eldest child, was an original partner of Howard Hughes’s father, and a younger brother, Hugh, built Highland Park. Hugh Prather, Jr., is handsome enough to be in movies, as is his daughter, Joan (Eight Is Enough, Smile), and literate enough to write his own book of stories and poems (The Circle of a Thought), as has his son, Hugh, a best-selling poet (Notes to Myself) who lives in Santa Fe. Hugh is also a fine tennis player and the inventor of a gourmet dish known throughout Highland Park as Hugo’s Burritos. Tall, silver-haired, broad-chested, perpetually tanned, Prather’s courtly manners would shame Rhett Butler. He spends his days selling HP real estate from his office in the Highland Park Village.

“I was born in a house over at Lexington and Byron, east of the lake here,” Prather said nostalgically. “Then my father built one of the big estates along Preston Road. I’ve lived all over Highland Park. As a boy I used to chase rabbits on horseback west of Preston and live all summer in the swimming holes where we are now. When you talk Highland Park I’ve seen it all.”

“I was born in a house over at Lexington and Byron, east of the lake here,” Prather said nostalgically. “Then my father built one of the big estates along Preston Road. I’ve lived all over Highland Park. As a boy I used to chase rabbits on horseback west of Preston and live all summer in the swimming holes where we are now. When you talk Highland Park I’ve seen it all.”

In 1929 Prather’s father and an architect named James B. Cheek went to Spain, where they were much impressed by the buildings they saw in Barcelona. Spanish-style architecture already had a foothold in Highland Park (the town hall, built in 1924 for $64,000, is a beautiful Spanish-style stucco building with a red tile roof), and the two men decided that style would be the perfect expression of graciousness and beauty for their small North Texas town.

There was only one other shopping center in America in 1929, a development called Country Club Plaza in Kansas City, Missouri, that had been built in 1920. The senior Prather and James Cheek proposed an entirely different concept from the Kansas City center, where the stores faced each other across a matrix of public streets. The Village would be built off the main traffic artery on private streets and the stores would all face a central parking lot. It would also be done in the familiar Spanish architectural style. The ten-acre Village opened in 1932 with a gourmet grocery, Harold Volk’s clothing store, and the S&S Tea Room, which still operates in the same building it did 48 years ago. The Village prospered along with the town’s growth and became Highland Park’s Main Street, a cozy, informal collection of family-oriented shops much like those found in any small town.

Hugh Prather, Jr., left Highland Park after college and saw some of the world, traveling in Europe and Asia, working on ships, then returning to work in the East Texas oil fields. “My dad tracked me down at the bottom of a 224-foot oil mine shaft, a straight shaft where you could obtain oil through seepage. He was putting together the Highland Park Village—this was right at the beginning of the Depression—and needed me to persuade store owners to settle away from downtown.”

Leaving the ancestral spring along Lakeside Drive, Prather toured the town his father built, outlining the pattern of growth: the earliest homes stand along Lexington, Gillon, and Miramar streets and the smaller homes on the town’s eastern edge, near the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad track. The Highland Park railroad station stood on the same spot from 1922 until June 1965, closing 43 years to the day after it opened (a building on Preston Road used by Heritage Savings is a re-creation of the station). Prather pointed out the site of the town’s first commercial business—Abbott and Gillon, an insurance company built in 1911—and the town’s first big mansion at Beverly and Preston Road, completed in 1913 by Rose Lloyd and her husband, Al, who came from Shreveport. Mrs. Lloyd is rumored to have once received a copy of the town’s budget and, thinking it was a bill, sent the city a check for the full amount.

“The big homes followed south from the Lloyds, along Turtle Creek,” said Prather. “Ed Cox now lives in the Lloyd estate; it has the big wall and indoor tennis courts. Governor Bill Clements lives down the street from them. Mrs. John Black lives where my family used to live. Next the cotton barons built along Beverly Drive and finally, in the mid-twenties, along Armstrong Parkway to the west. We had to plant trees before that area could succeed. Hackberries, not for looks but because they grew quickly despite the hot sun and little water.”

The most famous tree in Highland Park is a 75-foot-tall, 100-foot-wide pecan tree about sixty yards west of Preston and Armstrong. It was planted by Joseph Cole on the family farm just after the Civil War and was the only tree growing west of Preston Road for many years. In 1928 Hugh Prather, Sr., decorated the large tree with two hundred 10-watt Christmas tree bulbs, running the 220-volt power line underground to avoid putting up unsightly poles in front of the new houses along Armstrong Parkway. Since then the lights have blazed each year from about December 11 until the evening of January 1, except in 1973, when the town council voted not to turn on the bulbs because of the energy crisis. Today about 2500 red, green, and blue bulbs cover the magnificent tree each Christmas. On Highland Park Arbor Day, January 20, 1951, the Town North Civitan Club planted another native pecan tree thirty yards behind the first to take the place of the older tree when it finally dies.

Traditions such as the Christmas lights and neighborhood block parties and Fourth of July parades are maintained effortlessly in a town like Highland Park, which has changed very little in the past fifty years. In 1965, when the town council drew up the first new zoning laws since 1929, the rule was to preserve and protect, to modify only when necessary. Architectural boards and zoning restrictions had always protected the integrity of neighborhoods. Commercial buildings were allowed in only three areas: the Village, Lomo Alto shopping center, and a strip on Oak Lawn. High rises were permissible only where they already existed, just north of the Lomo Alto center. Although the Henry S. Miller Company owns the Village, the town council has to approve any major exterior changes. The council struggled for eighteen months before agreeing on standards governing the building of tennis courts on residential lots. Whether applied to business or home, the gospel of sanctified soil is a well-received, loudly preached doctrine.

Land is valuable in Highland Park not because of its fertility but because it is scarce. Many people who would like to live there do not. There are two adjoining vacant lots on Beverly Drive owned by a lawyer named Claude Miller who lives just north of the empty property. Each year Hugh Prather, Jr., calls Claude and asks the same question.

“Claude, you want to sell this year?”

“Hugh, do you know anyplace I can put that money and increase it any faster?”

“Claude, honest to God, I don’t.”

“Guess I’ll keep it another year, Hugh.”

That stock conversation is to satisfy the formalities. The two empty lots would earn Miller about $600,000 now, but next year their value will increase by 20 per cent. Prather relates tale after tale of houses doubling in value in two years, of ordinary fifty-foot lots selling for $1500 a front foot, of increasing amounts of Canadian and California money buying up Highland Park commercial property, of most of his recent buyers paying cash, of the $250,000 town houses and condominiums like the Mews of Highland Park going up just west of the Dallas North Tollway, one street inside the town limits. The landscape of Highland Park is being washed by a wave of inflated values, and there’s no end in sight.

To be one of the 8800 citizens living within the town’s 2.2 square miles guarantees a quality of life enjoyed by only a tiny minority of Americans. If you can afford to be one of the elite, a city awaits you that works well by any criterion. Four years ago the town ranked second lowest ($796) among 25 Dallas County cities in a survey analyzing the annual combined cost per capita of municipal services, municipal and school taxes, and utilities. Dallas placed seventh ($941). Only Highland Park’s sister suburb, University Park, ranked lower ($793).

Except for bicycle thefts and a recent rash of silver robberies, crime in Highland Park is negligible. In 1977 the town became the first in North Texas to consolidate the police and fire departments into a public safety unit. The unit is headed by Henry Gardner, whose father served as HP police chief from 1939 to 1950. It is not dangerous duty, and the cops receive their share of kidding about rescuing kittens from trees and watching homes of vacationing residents. It is preventive police work that sometimes includes following a tipsy driver home—only if he is a Highland Park resident, of course—instead of pressing a DWI charge.

In a town where the major institutional focus is childrearing, the school system ranks second only to the home in importance. The reputation of the Highland Park Independent School District has always been and is still one of the magnets drawing residents to the town, particularly since it is not involved in the Dallas Independent School District’s busing plan.

The latest results of the California Test of Mental Maturity show that the Highland Park student’s IQ averages 12 points higher than the national average of 100.

On the state’s new minimum competency test, given to 500,000 fifth- and ninth-grade students across Texas last February and March, Highland Park’s ninth-graders received the highest scores among Dallas-Fort Worth schools in all three skills tested. Highland Park fifth-graders ranked first in reading, third in writing, and second in mathematics.

Only one other Dallas-area school district has an average teacher salary level higher than the statewide average, and only the Highland Park district exceeds the state average in per-pupil expenditures. The Highland Park student-teacher ratio of sixteen to one ranks as the second lowest in Dallas County. In 1979 the high school placed thirteen students as semifinalists in the National Merit Scholarship competition, leading the county in the number of semifinalists per thousand of enrollment per grade. An average of 95 per cent of HPHS graduates attend college. It is not a question of whether they will go to college but where. Perhaps the most impressive fact about Highland Park is that the town accepts no federal money for anything—not for lunchroom programs, road maintenance, law enforcement, and certainly not for welfare.

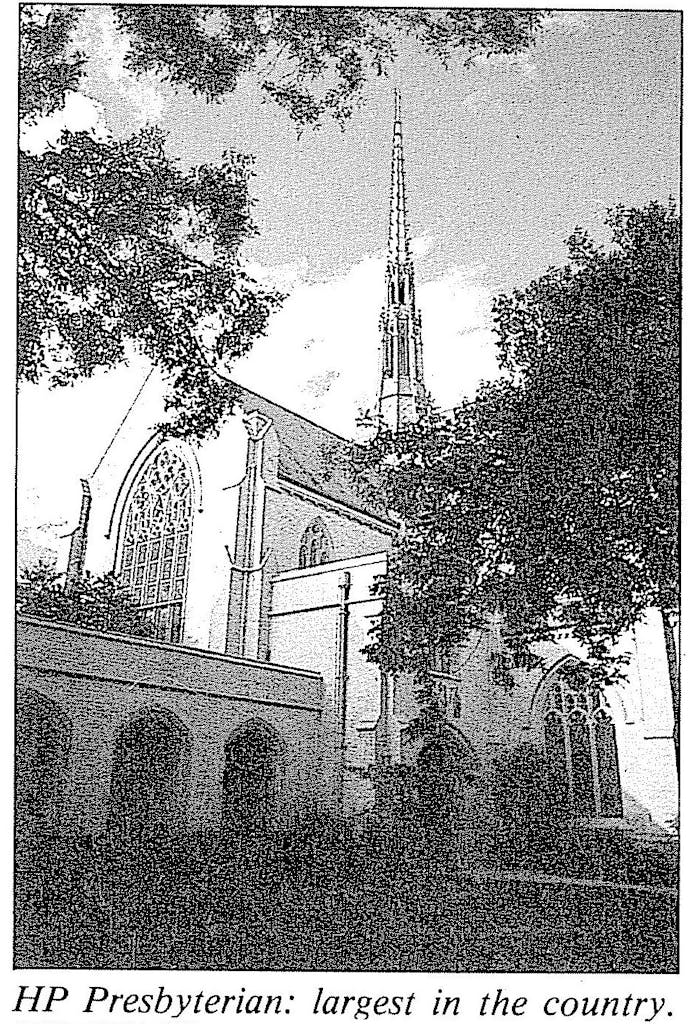

Back in his office, Prather gazed out his window toward the country club, where older men and women rode in golf carts along the lush fairways just across from the Village. “You know, Highland Park is not a town of churches. My father wanted them outside the town limits so the Sunday traffic wouldn’t clog the residential streets. Only a part of the Highland Park United Methodist Church is in Highland Park,” Prather said, chuckling. Close to the town his father kept churches out of is the largest Southern Presbyterian church in the United States, Highland Park Presbyterian; the second-largest Methodist church, Highland Park United; and one of the nation’s largest Episcopal churches, St. Michael and All Angels. His father had planned well, for the total membership of these three churches alone—imagine the cars required—numbers more than 20,000.

A Neighborhood Tragedy

Ann enjoys Junior League meetings only because she gets in a visit with Peggy Oglesby, the group’s president-elect. Actually, she regards Peggy with respectful awe, as do many of her friends who make it a point to drop Peggy’s name in conversations as proof that they are serious, thoughtful people and that the listener isn’t dealing with just your basic, large-bore Highland Park flit. Peggy enjoys this reputation because she is smart: bachelor’s degree from Smith College, master’s in mathematics from SMU, graduate work in number theory at Cambridge, creator of difficult puzzles for D and Houston City magazines. She encourages her son, John, to ride the city bus to and from St. Mark’s School, something unheard-of among her friends, and worked long and hard to get the town council to relocate the dangerously heavy animal-shaped swings and create a children’s play area near the public swimming pool. Ann sees Bud and Peggy Oglesby occasionally at the Highland Park Presbyterian Church. They both admit to feeling a bit lost in the crowd and wish the minister, Dr. Clayton Bell, would speak out more frequently on social issues.

While St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church can boast the social elite of Highland Park among its membership and Highland Park United Methodist has a larger congregation, it is the Highland Park Presbyterian Church that most represents the town’s churchgoing habits. This is not because of Presbyterian theology. Most members would have no ready answer if asked the differences between Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists. Among the affluent the choice of a church is based on a feeling of community more than anything else. It’s like choosing a spiritual country club: do your friends attend? is the range of activities (senior citizen domino games, preschool nursery facilities) large? is the minister dynamic? No longer is “leaving the church” the wrenching decision it used to be. Church shopping is permitted, even encouraged, either to find salvation or as a device to stay well connected.

Before their divorce Ann and Jack had switched to Highland Park Presbyterian so they could attend Jim Smith’s coed adult Sunday school classes (Wilshire Baptist had separated the sexes in its classes). As director of family development, Smith spends his days listening to problems arising from marriage, parenting, step-parenting, and personal difficulties, to tales of lechery, lack of fulfillment, and pain. His office is on the second floor of the new $5.5 million Hunt Building, one of three in the church’s complex, just below the gymnasium, weight-lifting and exercising rooms, steam bath, and meeting room where Jim Riley, director of recreation, holds his NFL Bible Study classes before Monday night football games.

The social changes of the sixties and early seventies—women’s liberation, drugs, sexual freedom, civil rights—bypassed Highland Park. It wasn’t the dawning of the Age of Aquarius but the continuing of the Age of Acquiescence.

When Jim Smith came to Highland Park seven years ago after working in Detroit’s inner-city ghetto, he thought he had stepped back into the fifties. It wasn’t just the town’s monochromatic white-as-cream population and high median income (five times the national average) and conservative tone. More surprising than anything to Smith was that the hurricane of the sixties and early seventies, with its accompanying winds of social change—women’s liberation, drugs, sexual freedom, civil rights, anti-war feeling, abrupt career turnabouts—had skirted the town of Highland Park, blowing around the edges and then moving on. No one seemed affected by the drastic events that were fundamentally altering the rest of the country. The place seemed frozen in time, the people locked in their paradise of childrearing, tennis dates, and small dinner parties. It wasn’t the dawning of the Age of Aquarius but the continuing of the Age of Acquiescence.

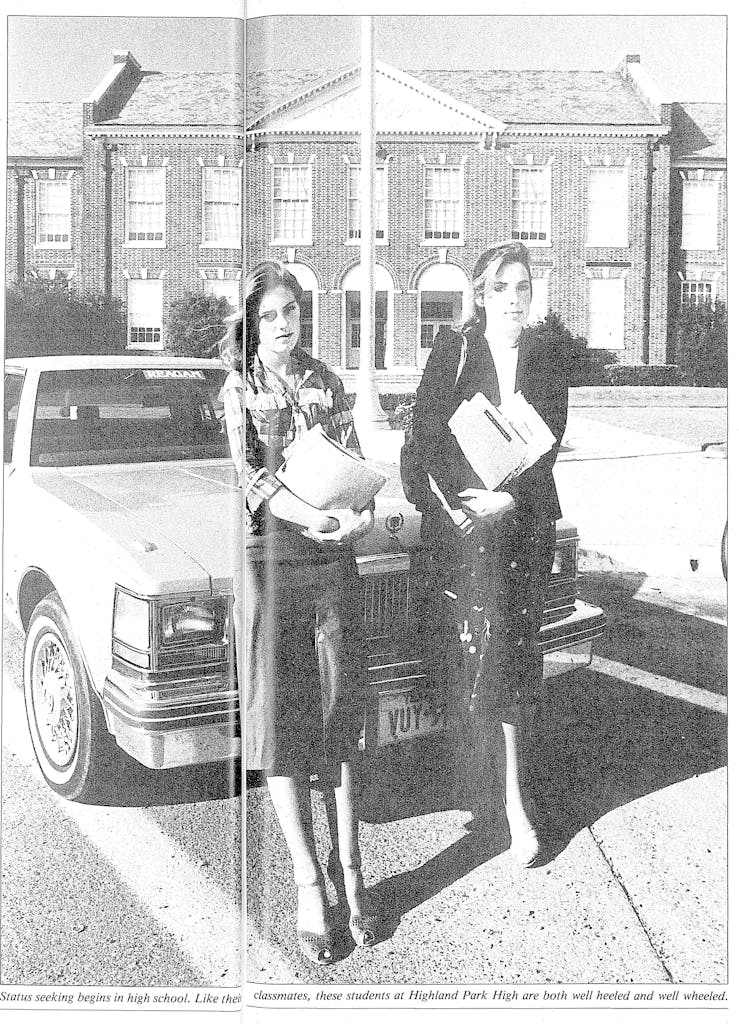

While Smith did not find social rage or lifestyle experiments, he did find inner turmoil and crumbling family bonds caused by abundance and stress. He found not drug addicts but pressured and harried status junkies. High school kids felt inferior driving old cars, lost confidence when they quit the football team and their girlfriends vanished, felt like failures when they were unable to get into the college of their choice. Two years ago, three fourths of the 389-member HPHS graduating class had A or B averages. Twenty-three per cent had A or A-plus averages. Teenagers are under pressure to perform in the classroom and on the athletic field (52 per cent of HPISD students compete on school teams), pressure to acquire, and most of all, pressure to conform.

This high-performance dogma seems almost an obsession with Highland Park citizens. “Did you know Highland Park kids total only ten per cent of the campers at Camp Mystic but win fifty per cent of the awards?” boasted a proud father over lunch at the Dallas Country Club. From the HPISD superintendent, Winston Power: “If there is one characteristic that best sums up Highland Park kids and their parents, it is that they’re competitive!”

Jim Smith, sitting in his cluttered office, agreed. “People here equate self-worth with achievement. A certain amount of performance is good, of course, but here in Highland Park, a town of strivers, climbers, movers, and shakers, there seems to be no choice. Most of these people never have had a chance to choose another value system. There is no room to be Joe Average. Christ didn’t put a lot of emphasis on success. By Highland Park standards He was a washout, a misfit.

“It isn’t much different with the adults I counsel. It is interesting that of the three major causes of divorce around the country—money, sex, and conflicts with in-laws—in Highland Park only money ranks high as a reason for divorce. With men it’s anxieties resulting from not achieving occupational goals—realizing they won’t become the company president—and money problems. With women it’s low self-esteem, loneliness, isolation, boredom despite all the running around. ‘Love things, use people’ seems to be the motto, not just in Highland Park but in most affluent communities,” sighed Smith.

There was no dramatic showdown or cataclysmic event that caused the death of Jack and Ann’s marriage. It was more the victim of a slow but deadly cancer that went unnoticed for years. On the surface all seemed healthy. Jack advanced in his law firm. They moved to larger houses, raised babies, vacationed at South Padre Island in the summer, skied the slopes at Vail at Christmas. They followed the Cowboys, Bluebirded and Cub Scouted, PTAed, and car-pooled. Jack took a weekly tennis lesson at Brook Hollow Golf Club and “did deals” at the club’s Nineteenth Hole. Ann jogged and worked the Armstrong School cafeteria lunch line. During the last years Jack buried himself in his work, and Ann’s life continued to resemble some kinetic art object, a Calder mobile moved by a relentless progression of tasks and schedules revolving around children and husband, scouts, summer camp, clubs, church, anything but herself. Her ubiquitous leatherbound datebook looked like an American Airlines timetable.

Somewhere along the way she and Jack lost touch with each other. Family logistics and finances dominated their conversations. Money bought expensive toys and allowed them to play the game a little longer. Toward the end a succession of counselors, including Jim Smith, sought to save the marriage. After the counseling the couple wept, embraced, and returned to their old ways. Finally it was over. They had grown tired of speaking carefully and wearing faces with expressions and feelings wrapped up tight as umbrellas. While Ann took the kids to a movie, Jack packed his suitcase and walked out the door.

For the first few months Ann could think of little else but leaving Highland Park. What had before appeared safe and secure now appeared boring, cautious, a refuge for people who lived in fear. While the rest of the world scratched out a living, Highland Parkers seemed exceedingly smug and carefree. How many times she had seen her friends shudder at riding through some parts of Dallas, rolling the windows up tight and locking the car doors, literally sighing with relief to be back on Beverly Drive. Weren’t they the bland leading the bland, making money and buying things, drawing their sustenance from the main city only to carry the spoils back into their tree-lined enclaves and ignore the rest of the world and its problems? There were days when the town seemed grotesque, but she also knew it contained decency, virtue, and a possibility for fulfillment.

It was a neighborhood tragedy that helped Ann regain her perspective about Highland Park. John and Stephanie May lived around the corner on Normandy Street. John was chairman and chief executive of May Petroleum and had lived in Highland Park most of his life. He and Stephanie had been married for 25 years and had three children. On a Sunday in March 1979 the plane carrying John, two of the children, and a son-in-law crashed in the Colorado mountains shortly after leaving Aspen. All were killed. The third child had flown home earlier in the day.

Later Stephanie said it was the Highland Park Presbyterian Church and her neighborhood friends that saved her life during the first dark days following the loss of her family. Partly to forget her own troubles, Ann spent long hours at the May house working and visiting with the hundreds of people who came by to express their sympathy. She gained a new respect for the church and its minister, Dr. Bell. Bell had brought the news of the tragedy to Stephanie and later urged her to write about the experience, which she did in a 43-page diary, “In God’s Hands.” It was Dr. Bell who urged Stephanie to speak in the church sanctuary about the role religion played in coping with her loss and to continue speaking around the country on dealing with life after losing four family members at once.

During this time Ann got to know her Normandy Street neighbors, developed friendships, was brought closer to these people she usually would see only through car windows, at the Village Safeway, or at Saturday soccer games. The lady she had thought pompous proved to be shy and blossomed like a morning glory with a little attention. The grump turned out to be agreeable. In the collective mood of shock and sympathy Ann learned to look past the stereotypes and see her fellow folk without prejudice.

Open the Doors and Here Are the People

One early evening when the city was wrapped in its accustomed quiet, she walked down the 3700 block of Normandy and thought of her new friends not with the old air of mock damnation but with affection. Twenty houses lined the street, ranging from low-slung modern ones to modest brick homes built fifty years ago. Ann’s friends who lived elsewhere thought Highland Park was populated only by nabobs, plutocrats, and heirs of Midas, Croesus, and Mammon. That view could be prophetic if real estate prices continued to climb, but Normandy’s residents bore a greater resemblance to a tourist group. There were three retired couples, four divorced women (among whom were a Ukrainian geologist, a woman who had the morning paper route, and the first wife of football great Doak Walker), ten married couples (including two doctors, an aerospace executive, an architect, a realtor, a salesman, and an electronics engineer), one recluse, one empty house, and that rarest of Highland Park creatures, a bachelor, who flew with American Airlines.

Soon after the May family’s tragedy, the Swearingen family—Barbara, Wayne, and their fourteen-year-old daughter Shannon—moved into their new house just east of the Mays’ modern home. The dwelling is a curious marriage of home and town house, fronted by a curved driveway instead of a lawn, backed with a swimming pool and Wayne’s “piddling room,” a workshop filled with tools and gadgets. They hosted two housewarming parties, one for Wayne’s business friends and employees of the Swearingen Company and one for the block. Ann decided to attend, for she seldom missed an opportunity to see how other houses were decorated.

Among the young to middle-aged residents the typical Highland Park decor is bright and lively, lots of lime green and yellow, with plants, flower-print fabrics on the walls, an oriental rug or two with double borders, plenty of brass and wood, a smattering of English antiques, here a Queen Anne-style table, there a Sheraton sideboard, chintz gathered on curtain rods, wicker furniture in the sun room, hardwood floors—a semi-eclectic, new-fashioned look, always very nice and reaching for sophistication but very much like a furniture store. None of this for the Swearingens. The house reflects Wayne’s recent success in real estate: an art deco bedroom, a huge playroom done in plum with a pinball machine and a TV connected to a Betamax, a Jacuzzi in a sunken tub, steam outlets in the shower, a temperature-controlled wine closet, a bedroom fireplace, and a redwood deck above the pool.

Wayne’s study expresses his love of hunting with pictures of his annual elk hunt and his white-wing bird shooting expeditions. His library reveals his fascination with World War II (Hitler’s Letters and Notes, The War in Europe, and Return to the Philippines). There are also a number of sports mementos. The Swearingens hold season tickets to the football games of Highland Park High School, the Baylor Bears, and the Dallas Cowboys. Until this year, they also went to all the SMU Mustangs’ games. They play tennis at the Inwood Tennis Club, have a box at the World Championship Tennis tournament, and have attended two Super Bowls. During the past year they spent May in Europe, Easter at Grand Cayman, and Christmas at Vail (after the October elk hunt) and made several other trips on business and to escape the summer heat. Barbara skipped the hunting trips in favor of a Mexican spa near Ixtapán.

Barbara and Wayne have been married seventeen years, the second marriage for both, and they have worked hard to achieve their bounty. From apartments in Garland and Irving they progressed to successively larger homes as Wayne’s career prospered. They lived for seven years in a much larger home in North Dallas before moving to Highland Park. What prompted the move was concern for their daughter’s education.

“We moved from the White Rock area so she could attend Hillcrest instead of Bryan Adams. Then, after the busing began, Hillcrest began having problems. The teacher excellence declined. And the school turned out not to be what we expected,” said Barbara, sitting in her huge, vaulted living room, which she calls the “talking room” because it has no television. “Shannon knew Highland Park kids from her summers at Camp Longhorn and from the Junior Assembly dance club, so the transfer worked out fine. She started her freshman year at Highland Park High and her communicant’s classes at Highland Park Presbyterian, where we transferred earlier in the year. She has big sisters assigned to look after her from the church and school.” When Ann’s daughter, Shana, also a freshman, met Shannon Swearingen she breathlessly brought home the news that Shannon’s parents had bought her an MG sports car two years before she could legally drive. Ann later saw the car sitting behind the Swearingens’ home.

Caryl and Wilson Jaeggli, who live six houses east of the Swearingens, also moved from North Dallas because of the effect of busing. Their daughter Carron’s school in North Haven would have been Pershing Elementary. Its enrollment was soaring—mostly black students bused in—and Caryl, a former teacher herself, believed the educational quality had dropped dramatically. She and Wilson were committed to public schools, and Highland Park seemed to be the only place where they were working. So three years ago they bought their Normandy Street home for about $75,000, putting another $30,000 into remodeling (now they could sell it for around $200,000).

Although she was convinced that the move was the right one for her children, Caryl worried about how the town would affect her. She expressed her fears in a twelve-page letter to her best friend. Would she sacrifice her identity and fall prey to social nonsense? Would she become her children’s alter ego and shadow like one of her friends, who unconsciously said, “We started first grade today”? She found that those dangers were indeed part of life in Highland Park and she notes that it took an effort to resist community pressure enough to retain her own identity.

“People say we live in a bubble or under a protected cover. I like to chip away at the eggshell from the inside,” says Caryl. “I work hard at seeing other types of people, exposing my kids to other lifestyles, doing lots of things myself to remember the rest of the world isn’t Highland Park. I am a fourth-generation Dallasite and I really identify with Dallas. The best thing about Highland Park is that it resembles the Dallas I grew up in, an intimate, friendly, small town. It’s a good place to live, but it can be confining. It takes a lot of work to keep growing.”

While Wilson Jaeggli works six days a week to ensure the success of his year-old aerospace electronics company, Caryl pecks at the eggshell by writing freelance articles, working as a copywriter for the PBS television station, serving as a volunteer counselor for teenage girls, preparing reports for the women’s book club, and working at her children’s school and her church. The young Normandy Street women lead a fast-moving, overflowing life, some to escape tedium’s domination, others to avoid the smothering bubble, and still others to be sure of remaining under its protection. “I don’t do solitude.” Those words are heard all over town.

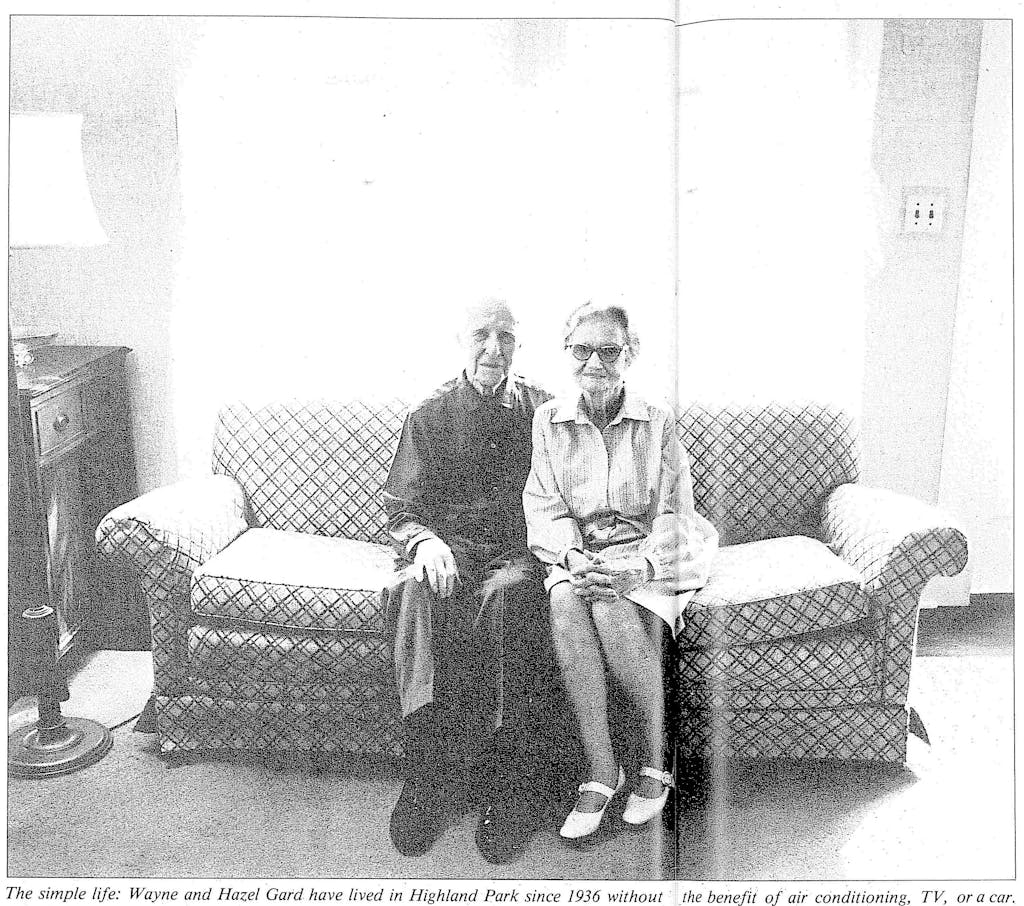

Ann’s favorite couple on Normandy Street have a house where one can see the rarest sight of all in the affluent tropics of Highland Park on a hot summer day: open windows. Since Columbus Day, 1936, Wayne and Hazel Gard have lived in their two-story home without ever owning air conditioning. They don’t worry about subscribing to cable television because they have never owned a TV. They have never sat in a gas line because they have never owned an automobile. “Actually, there’s one other house on this block that isn’t air-conditioned,” says Wayne. “Of the rest, two houses have window units and sixteen have central air. Nothing changed the face of Highland Park more than the installation of central air conditioning. All the houses closed up.”

Retired from the Dallas Morning News since 1964, Wayne, who is 81, has authored eight books in his open-air quarters, books on the American West he learned to love from watching Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Shows as a child in the Midwest. Hazel, 79, no longer walks to the grocery store with her cart as she did for 34 years. She now pays an additional $1.50 for the Simon David store’s Thursday morning delivery, but she still makes her own bread. The Gards have never felt the lack of a car. They ride city buses to Fair Park, walk to nearby SMU for concerts and plays, and take taxis when necessary. They have traveled to San Francisco, Boston, New York, New Orleans, Yellowstone National Park, Quebec, and even to Europe. Gard’s only regret about never owning a car is not being able to research books on the East Texas oil field and the Brazos River.

If the younger couples on Normandy who fill up their lives with everything imaginable would think of the Gards’ long and happy marriage, their simple, unaffected way of life, their sense of contentment, they might wonder if climbing off the merry-go-round of happenings and thinning out their possessions would bring them happiness, would help keep their marriages alive, would help make sense of this perplexing life. Who could say? The real question is this: is it the character of people that makes the place or the other way around?

“Cute, Y’all”

Ann relaxed as she sat with her children in the Los Vaqueros restaurant waiting for their food. After dinner they were going a few doors down to Harold’s, the source of most of the clothes in the room. What struck a newcomer right away about the Highland Park teenagers gathered in the restaurant was that they were uniformly dressed and uniformly pretty. A small alligator or polo player adorned the left breast of their shirts, which were almost all lavender, pink, or blue. Dark brown Bass Weejuns penny loafers encased the feet. Designer jeans covered the girls; Wranglers and Levi’s the boys. Khaki Gurkha purses, James Avery dangling-cross rings, add-a-bead necklaces, and multistriped belts, hair ribbons, and watchbands completed the look. Pseudo-Cartier tank watches, not really Cartier’s $650 model but $95 look-alikes with the same square, flat dial, were on almost all wrists.

It was a room full of smooth, tanned complexions, bold Roman noses with well-defined arches, clear eyes, flat jaws, noble necks, and healthy, well-cared-for hair. There was no ugliness in the place, no ragtag youths with pockmarked faces, no missing or even crooked teeth, no obesity or signs of poor nutrition. They sat eating bean-and-cheese nachos without onions and sipping beer and iced tea, their faces expressing vagueness but not vacuity, blankness but not stupidity. It was a look of being committed to nothing in particular—above all, an attitude of confidence that assumed little or nothing was beyond their control. Self-possessed, easygoing, genial, they exuded a mood of pleasant expectation and gushy self-confidence.

These were not children of aristocrats, although some did belong to Dallas’s first-cabin families; they were mostly Highland Park upper-middle-class kids, products of careful Anglo-Saxon breeding, raised in affluence in the spotless town of winding, tree-shaded streets and quiet beauty, set far apart from congestion, industry, poverty, slums, and—except for servants—people of a different color. Because of where they lived, these children enjoyed the best educational, health, recreational, spiritual, and residential advantages Texas had to offer. Because they had grown up in a comfortable world of abundance, they had every right to expect that the good, comfortable life, was their destiny, to continue associating seasons with vacations, to have unlimited confidence about the future. Most would expect these things as a right, not a privilege.

With cries of “Cute, y’all,” “Tons fun, y’all,” and “Oh bull tell me no, y’all” (the 1980 version of “far out” or “oh, wow”), a group of girls at a nearby table discussed the recent day of havoc at the high school. All hell had broken loose in the lunchroom. A smoke bomb exploded. Hundreds of BBs rolled across the floor. Students tripped and stumbled and crashed into tables and chairs, falling over the invisible fishing line that had been wound around the furniture legs. Playboy magazine centerfolds had been stuck to the slide screen. Someone said the front hall had been greased, but none of the girls used that hall anymore. The sack lunches of a few selected students had been switched with brown bags containing dog droppings. “It was tons fun, y’all,” squealed one of the girls. Actually, it sounded like a refreshing display of adolescent antics in a school where the student body is not so much the wild ones as the mild ones, almost frozen solid with sophistication and coolness. They have not had a lot of training in displaying emotion.

Chandler and Betty Bunton, best friends and seniors at Highland Park High School, often join their friends at “Los Vas” after their Saturday morning jobs at the Initial Place, a monogram shop in Preston Center. Laura drives over in her dad’s old blue Mercedes and Betty in her baby-blue Buick Regal, which she hates. It is four years old, a hand-me-down from her brother; worse, it has no air conditioner. The excitement of driving faded long ago for both girls. Now they only enjoy driving their parents’ bigger, more comfortable cars, either their mothers’ station wagons or, best of all, their fathers’ cars. Laura’s dad has a new Cadillac Eldorado.

Chandler and Betty Bunton, best friends and seniors at Highland Park High School, often join their friends at “Los Vas” after their Saturday morning jobs at the Initial Place, a monogram shop in Preston Center. Laura drives over in her dad’s old blue Mercedes and Betty in her baby-blue Buick Regal, which she hates. It is four years old, a hand-me-down from her brother; worse, it has no air conditioner. The excitement of driving faded long ago for both girls. Now they only enjoy driving their parents’ bigger, more comfortable cars, either their mothers’ station wagons or, best of all, their fathers’ cars. Laura’s dad has a new Cadillac Eldorado.

Both girls are truly beautiful, as pure and pristine and refined as the town they live in. Laura, raven-haired, freckled, taller than Betty, could pass for a college freshman. She was five when her family moved to Highland Park from Lookout Mountain, Tennessee, another affluent community. She grew up on Gillon Street in Old Highland Park, within walking distance of elementary and junior high schools. Laura’s family belongs to Brook Hollow Golf Club, the most prestigious in Dallas, and to St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church. Religion plays a large role in her life. She prefers the Sunday school classes at Highland Park Presbyterian but the sermons at St. Michael. She attends the Monday night meetings of the Northwest Bible Church’s Young Life religious group, probably the second-largest social gathering of Highland Park teenagers after the Friday night Highland Park High School Scots football game.

Brunette and button-cute with bright, sparkling eyes, Betty Bunton looks not a day over fourteen. Her father works as an executive at a large Dallas bank and she has two brothers and a sister. She too is a member of Young Life and attends Highland Park Methodist Church. Her family belongs to the Dallas Country Club.

Their clothes, friends, associations, and school activities identify both girls as “socials,” the largest high school societal cluster, the smart set who dress preppie, date boys on athletic teams (especially football), love the school dances, and look forward each winter to the main social event of the year, the Junior Symphony Ball, held at the Apparel Mart. They generally avoid the “freaks” and the “brains,” the other two HPHS groups. Freaks attempt to grow their hair long (of the Dallas-area high schools, only Highland Park and Mesquite enforce hair codes), tune cars, and play in rock ’n’ roll bands. Brains serve on the literary board and write for the Tartan (the school literary magazine), join the Round Table discussion club, and participate on the debate team. Brains resent the socials who are in their honors program classes because the socials don’t answer questions in class and they use Cliff’s Notes and other brain-stuffing-in-a-hurry devices.

For Betty and Laura this senior year at Highland Park High has turned serious. Because the football team is good, maybe great, maybe going all the way, the players wrap themselves up in pregame jitters and post-Friday night exhaustion. On Saturday nights a large group usually gathers at one of the guys’ houses to watch TV, or sometimes to go to a movie or have dinner at Judge Beans, Chili’s, or Reggio’s Pizza. The group isn’t playing as many pranks (“doing queer things”) this year as in the past, no tennis-shoeing of cars (darting out of the dark and running over the hood, roof, and trunk to startle the lovers parked along Lakeside Drive), no egging of cars or putting trash bags filled with leaves in the middle of streets. Both girls realize that a stage in their life is ending, that a plateau has been reached. College and adulthood loom ahead.

Laura has narrowed her college choices down to Hollins, Mary Baldwin, Alabama, or Ole Miss; she wants to become a dental hygienist. Betty likes retail work and thinks she might study business at Ole Miss, UT, Arkansas, Alabama, or SMU. Laura and Betty both want very much to return to Highland Park after their schooling.

“I know it’s sheltered and protected, but, it’s a great place to raise children,” said one Highland Park senior. “There are just good people here, not like in Austin with all those longhairs who wear dirty clothes and rub up against you. I think it’s real scary to go to school with blacks and I’m glad I don’t have to. I’ve grown up in a real prejudiced family and it’s sad, but that’s the way I am. I’ve been around kids with money all my life, at Camp Longhorn, at church, at school, and I know that will always be important to me. I know I want to stay at Hardin House at UT because so many Highland Park people will be there. And I know I will want to marry a guy who has lived like I have.” Thus the torch is passed.

Polos or Izods, That Is the Question

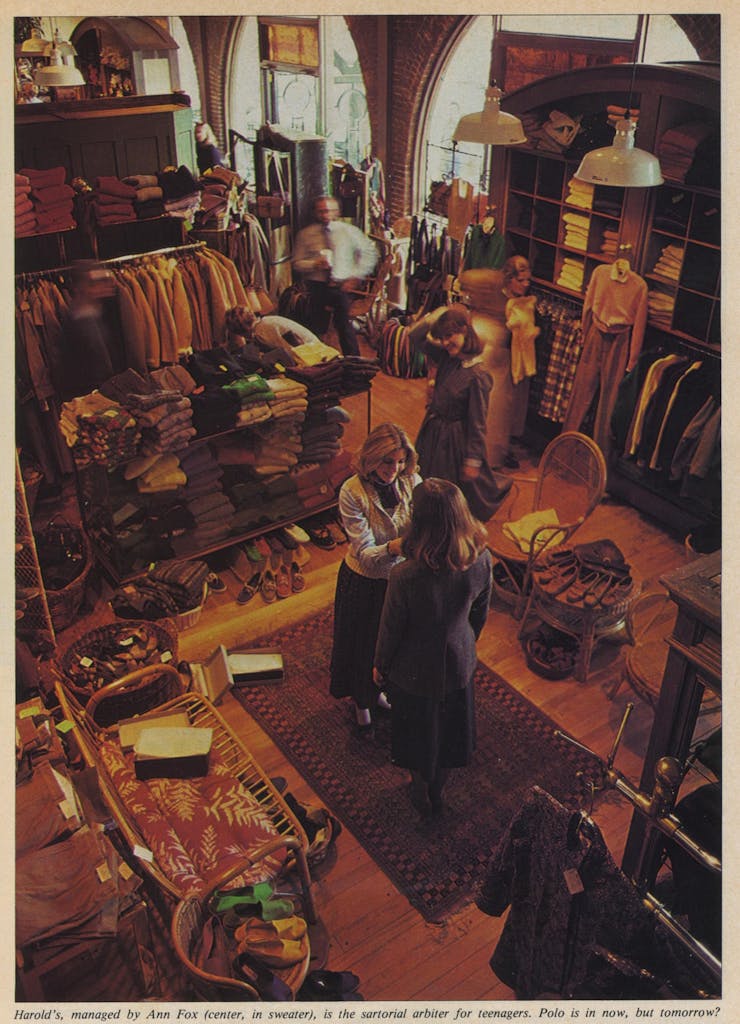

Ann and Shana walked down the newly bricked Highland Park Village sidewalk to Harold’s with friends they had met at Los Vaqueros, and soon the postprandial aroma of Mexican food wafted through the store. Some of the young women and a few mothers examined the new Shetland sweaters and sweater vests, while others quickly depleted the supply of lavender Polo shirts. Colors were important. Last year’s favorite, pink, had been replaced by lavender; burgundy and yellow were the most popular sweater vest colors; khaki was always in favor. Camel corduroy blazers, tortoiseshell combs for the hair, barrettes with bows attached, Ralph Lauren Polo socks—all were rapidly disappearing from Harold’s shelves. The young customers paid mostly with cash and check, a few with credit cards. Many asked the salespersons to hold a selection. Harold’s sales staff knew that Monday would bring the two M’s: mothers and money.

During her three years at Harold’s, manager Ann Fox has witnessed a phenomenal increase in teenage spending. Now no one seems to mind paying $95 for a ninth-grader’s original Gurkha purse or $54 for a skirt for a fast-growing eighth-grader or $26 for a string tie. Each week Fox orders dozens of multicolored hair ribbons that sell for $5 apiece and never has enough. Even after the Polo oxford-cloth shirts went up in price, she couldn’t keep them in stock. Price increases often signal the beginning of the end for an item. It is too early to tell for sure, but the cognoscenti predict a swing back to Izod alligators and Cole Haan loafers ($55) and away from Bass Weejuns ($39) because the latter will soon be machine made and not hand stitched. “When I saw the Safeway checker wearing a Polo shirt I knew that was it,” said Ann Fox. Polos have become the new Highland Park T-shirts.

Not only fashion but dating habits and cosmetic expertise have changed drastically in the past few years. Not too long ago seventh-grade girls had to ask their mothers whether they could shave their legs. They didn’t talk seriously to boys until the ninth grade. Now eleven-, twelve-, and thirteen-year-olds are wearing panty hose, dating, mastering complex cosmetic treatments, and arbitrarily becoming blondes. Constance Adams, a HPHS junior, transferred to the Arch McCulloch Middle School six years ago from New Haven, Connecticut. She was stunned at what she found, what she had to learn.

“Makeup? Topsiders? Panty hose? Boyfriends? What, are you kidding? I’m eleven. What is this?” Adams says, remembering those first days of middle school culture shock. “These kids were playing grown-up, and they had barely mastered fractions.”

Fads, trends, and styles are nothing new to Highland Park or any other affluent suburb. They come and go out of concern for both status and conformity. With the relaxation of economic fears, fads flourish and options become a way of life. The list of choices is endless: Aspen or Vail; Polo shirts or Izods; cable TV, videocassettes, or both; mopeds or motorcycles; Valium or Luminal; tennis or golf; est or Bill Gotherd; a Mercedes diesel station wagon or a Buick station wagon.

One high school senior has seen this change in her own family. “There were certain things my older brother couldn’t do until his senior year in high school. My sister could do those things her junior year, and I did them as a sophomore,” said the girl. “Now my little brother comes home and watches 10 on TV. It’s not right. He’s in the seventh grade.”

Perhaps the alterations in the Highland Park Village shopping center could also be explained by this change in habits, this conversion of luxuries into necessities. After the Henry S. Miller Company bought the Village in 1976, many of the long-established service-oriented shops began leaving: Roos Electric Repair Shop; Oriental Cleaners; Shiner’s Stationery and Gift Shop; A&A Liquor Store. The new owners tried to oust two of the center’s mainstays, Hall’s Variety and the S & S Tea Room, but howls of outrage from longtime customers resulted in their reducing Hall’s space by half and remodeling the Tea Room.

The Village managers replaced these useful, family-style stores with shops carrying expensive, exclusive items: Ralph Lauren Polo; Courreges; Guy Laroche; Bonds Jewelry; Cafe Pacific; several art galleries and costly gift shops; the Village Garden, owned by oilman Ed Cox’s daughter Chan Cox Mashek; and Billings Village Hardware, which is famous for not stocking screws, bolts, extension cords, and other fix-it basics. It seemed to many Highland Parkers that the Village was becoming a shopping center for the very rich, a circular Rodeo Drive appealing chiefly to the Lakeside Drive mansion dwellers and giving only a slight nod to the common man with Skillern’s, Sanger Harris, and Safeway.

The Village’s managers deny that its character has changed, deny that they are driving away established tenants by not offering an opportunity to renegotiate leases. It is clear, though, that the emphasis is no longer on Main Street, USA, but on dollar return and sales volume per square foot, which has risen to an average of $350 in the 220,000-square-foot center. Some customers applaud the Miller regime. They say the Village had become run-down and shabby and needed some shops with class. But considerable grumbling about the regrettable changes in “our” Village is heard at important gatherings like the Old Highland Park Bicycling and Seated Whiskey Club, a group of 35 or 40 powerful and respected women from Old Highland Park, such as Ruth Virginia Drewery, Marge Steakley, and Betty Gertz, who meet once a month for no bicycling, a little whiskey, and a lot of talk. It was bad enough when Everett’s Jewelers left, but now Jockroy Linens? If this continues, OHPBASWC members say, we shall have to consider going to Snider Plaza in University Park or even to Dallas. Now that’s serious.

The Village Liberal

The outrageous prices paid for moderate-sized homes, the snobbish direction taken by the Highland Park Village, the town’s young people embracing and becoming accustomed to a rich lifestyle—all that suggests that Highland Park is growing even more exclusive. The town has actually lost population since 1950. No more moderate-income families will be moving in, partly because of high real estate prices and partly because the town has prohibited the installation of ranges or other cooking equipment in servants’ quarters and guest rooms, preventing their conversion to rental property. And as for black or brown Americans buying a home there—well, it just isn’t done.

Except for those who served the owners of the mansions and stayed in the quarters behind the big house, blacks and Mexican Americans never have lived in Highland Park. In 1971 a group called Grass Roots, Inc., headed by Curtis Gaines, singled out Highland Park as a target area for future property ownership by blacks. Blacks who had lived in Highland Park had been servants and slaves, said Gaines, and it was time to remove the stigma of second-class citizenship. A civil rights activist named Mary Jo Vines sold Gaines a house at 4816 Abbott for “ten dollars and other valuable considerations.” After the publicity died down, Gaines moved on.

Except for those who served the owners of the mansions and stayed in the quarters behind the big house, blacks and Mexican Americans never have lived in Highland Park. In 1971 a group called Grass Roots, Inc., headed by Curtis Gaines, singled out Highland Park as a target area for future property ownership by blacks. Blacks who had lived in Highland Park had been servants and slaves, said Gaines, and it was time to remove the stigma of second-class citizenship. A civil rights activist named Mary Jo Vines sold Gaines a house at 4816 Abbott for “ten dollars and other valuable considerations.” After the publicity died down, Gaines moved on.

Exactly one black has graduated from Highland Park High School: James Lockhart, who transferred from San Antonio as a junior in 1974. So Highland Park children experience people of different races not as fellow students but as servants, people who provide convenience and comfort for them, who aim to please. They also get to know and become fond of a few conspicuous blacks: Eloise Walker, who works at the Dallas Country Club; Leon Cunningham, who handles groceries at the Village Safeway; Randolph, the Highland Park yardman king with his truck and his crews of workers; and the squad of shoeshine men at the Village Barbers.

Certainly, real estate prices constitute the main barrier to the integration of Highland Park. The town never has had a law prohibiting the sale of a house to a family of any certain race. It just never happened. When asked why even wealthy black families haven’t settled in the town, citizens almost unanimously reply, “They want to live with their own kind just as we do”—more or less the we’re-tolerant-but-you-gotta-be-realistic view of social groupings. J. D. Hancock, the retired town administrator, perhaps comes closer to the truth. “Any black rich enough to live here is smarter than that. He’ll live in North Dallas, where he can get a lot more house for his money. The prestige and mystique of Highland Park doesn’t mean a darn to him.”

Highland Park’s most liberal couple arrived fourteen years ago, after ten years of academic life in two of the nation’s most liberal communities, Berkeley and Ann Arbor. Paul and Oz Srere came to Dallas when Paul, a biochemist, accepted a job at the Veterans Administration Medical Center. They made one trip to look over Dallas before moving, and a real estate agent drove them around Highland Park. They expected an all-white, conservative suburb, and that’s what they found, but they were delighted by its old-fashioned look and quiet beauty. Proximity to schools and shopping centers was especially important to a couple who had imposed a rule that their four children could do just about anything as long as it did not require their being driven by a parent. A few weeks later the Sreres bought a handsome two-story home across from a small park, sight unseen, after the agent described the floor plan over the telephone.

Paul brought to Highland Park one of its first beards, not the close-trimmed face fuzz favored by ad men but a long, dangling affair that gives him the appearance of a Hasidic rabbi. He is in fact Jewish, although he and his wife do not believe in any religion. Another oddity the Sreres brought with them was old cars. The courteous but firm HP police, always suspicious of old cars driving Highland Park streets at night, frequently stopped Paul and Oz at first, and it still occasionally happens when Paul drives his old Ford, which has over 160,000 miles on it.

Despite their different background and iconoclastic nature they have enjoyed their life in this city where the citizens fundamentally differ with the Sreres on almost every topic. They found their neighbors in Highland Park more honest than the phony liberals in Berkeley who preached school integration and then scrambled to move or to transfer their kids to private schools when it arrived. Paul, who teaches part time at the UT Health Science Center, helped organize a “free university” at Lee Park, and Oz worked to raise her neighbors’ consciousness about maids’ salaries.

“It has been good for our kids to grow up where they have to defend their unpopular viewpoint every step of the way,” says Paul. “It’s easy to be a liberal where we used to live. Here they had to think through their position under heavy pressure to conform, and they are stronger for it. My main quarrel in Highland Park has been with the school’s enforcement of arbitrary rules—hair and dress codes—that weren’t really policy, just used to control students. This year you can wear T-shirts. Last year you couldn’t. I have been in schools all my life—studying, teaching, researching—and never have I seen a single case of learning disability caused by long hair or a certain kind of clothes.”

The Great Decision

Ann sat in bed and watched the moonlight edge across her empty lawn as up and down her block, windows darkened and the town began to slumber, deep in anonymous silence broken only by the swish-swish of sprinklers and the infrequent mutterings of traffic. The kids—fed, washed, homework finished—slept down the hall. Ann was tired. Her brain felt unappreciated, her nerves worn. She was trying to decide between taking a Valium and reading Arnold Toynbee. “That’s a decision?” she could hear her cynical, witty friend Jean say.

Ann thought of her meeting with Jack, at which they had discussed the further dismantling of loved, familiar things, the baggage of years of marriage. He had come straight from work, one of the hundreds of thousands in the tide struggling toward home along the freeways. Home for Jack now was a high-rise apartment on Turtle Creek, a honeycomb filled with many recently divorced middle-aged men. The Stoneleigh Terrace served the same purpose for older men. Heartbreak Hotel, they called it. Men moved out, got an apartment, went to work, saw the kids once in a while, and rejoined the libidinal race with hardly a pit stop. Jack had sprinkled their conversation with allusions to country-and-western dance lessons, hot tubs, and learning to “reach his feelings.” Despite his chatter of a new and exciting life, he looked tired and had gained weight. As he rose to leave, his ponderous body reminded Ann of a jumbo jet lumbering down the runway. Despite the strain of her own new responsibilities, she did not envy him. “Farewell, sleep well,” she had said to the man she had lived with for thirteen years.

Ann put down her book and reviewed her long day, thinking of the contradictions of Highland Park that troubled her. She lived in a paradise of man-made and natural beauty, in many ways the reincarnation of a country village, though an increasingly expensive one. Living here simplified many things for her, relieved her mind of fears mothers elsewhere in Dallas constantly fretted over—crime, filth, traffic, pollution, racial problems, substandard schools. Her neighbors were, for the most part, decent sorts who invested tremendous energy in their domestic lives, practically cloistering themselves with the family and dropping any but vocational and vacational contacts with the world.

But these undeniable truths weren’t really important. What really mattered was how the Highland Park children were turned into adults. What ideals were offered to them? The point was to produce not winning football teams or good-looking business executives but young people who would become good citizens and who might solve a few of the world’s problems. Was this possible, given the town’s homogeneous character, the lack of cultural and racial diversity, the atmosphere that did little to promote tolerance of social and cultural differences among Americans? Was the town a breeding ground of prejudice, destructive social snobbery, and false values—too tidy, too neatly packaged, too caste-ridden?

“That is part of it,” Ann thought. You can’t have low crime rates, high property values, quiet and clean neighborhoods without paying a price. The bubble of Highland Park was both soothing and stifling. She would do her best to ensure that her kids would not feel they were “entitled,” would not become materialistic and racist, ignorant and fearful of people on the other side of the tracks. She had no doubt that she would stay in Highland Park where she felt safe and secure. She would accept and enjoy its virtues and continue to worry over its subtle corrupting influences. She would go through her predictable, unvarying days of duties, responsibilities, and projects, raising her children, making new friends and a new life, committing herself to this unique community, ignoring the occasional warning signal until it threatened to drown out all other sounds.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Longreads

- Dallas