This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Here’s another one,” Randy Shell said, opening a manila folder. It was a Monday morning in July 1998, and four women in their early twenties were gathered around his desk in his spare North Austin office. “A mother is reported to be living in a cheap motel with her children, ages two and four. She’s using all her money and food stamps for crack. The kids are left alone all day in the motel room. They’re not being fed.”

Randy ran a hand through his long salt-and-pepper hair and stared at the women. Their faces were blank; the fluorescent strip lighting had drained the color from their cheeks. Already that morning they had divided eight manila folders among themselves, and another five were still sitting on Randy’s desk. “There’s just one problem,” he said matter of factly. “All we know is that Mom is in some motel along Interstate 35. She keeps moving from one place to another. No one knows what could be happening to those kids.”

The women seemed frozen in place, their eyes focused on the folder. Randy didn’t need to be told what they were thinking: Don’t give it to me. Don’t give it to me. This was a “door knocker,” a case that could require an entire day of knocking on doors of fleabag motels. None of them had time to play detective, though that is exactly what they had been hired to do. They were members of Unit 25, a child abuse investigative team for the state’s Child Protective Services (CPS) office in Travis County, and as they had been told over and over in their training sessions, they were the last line of defense for helpless children. It was their job to keep kids from getting their cheekbones crushed by beatings or their skin stripped away by scalding water. They were supposed to find the sick toddlers turning jaundiced from lack of medical treatment and the helpless grade-schoolers who stifled screams at night while an uncle or a stepfather fondled them.

For several seconds, the 38-year-old Randy, Unit 25’s supervisor, studied his caseworkers and wondered who was going to quit first. They were all rookies—they had been with him less than a year—and he had no doubt that they were all thinking about resigning. CPS has the highest employee turnover of any state agency: More than one out of every three caseworkers quit within twelve months. Randy was a rarity, an eight-year veteran who wanted to stay in the investigative division. He was something of a legend around CPS, so dedicated to his job that he occasionally spent the night on a bedroll on the floor of his office.

“Anyone interested in the motel case?” he asked. Standing at the far left of his desk was one of his best staffers, Christine Cheshire, a thoughtful 23-year-old who carried a Carson McCullers novel in her car to read during her breaks as a way to keep herself sane. On this day Randy had given her two case folders, and both needed immediate work. The first concerned a two-year-old girl and her ten-month-old sister, daughters of teenage parents who lived in a mobile home. The older girl reportedly had little round burns on her ankles, the kind made by lit cigarettes; she was also vomiting blood. The second folder told the story of a three-year-old boy who was seen standing alone in front of his house at two in the morning. The person who called CPS’s 800-number to file the report had said the boy’s mother regularly left him outside with a bag of potato chips while she went off to prostitute herself to buy drugs.

Christine might have been able to handle the two cases if there were not forty older folders already piled up on her desk. Unlike the ones Randy was passing out, most of those did not require instant attention, but she knew that if she disregarded them for too long, they were liable to blow up in her face. On her desk, for instance, was a report on an eleven-year-old boy who had told a teacher at school that he had seen his father hit his mother over the head with a lamp. His father had then picked up a piece of the lamp and pointed it at him. Because there was no evidence of abuse, Christine was supposed to close the case. But she couldn’t do it. In her conversation with the boy, she could sense how scared he was. He kept licking his lips and looking over his shoulder as she talked to him.

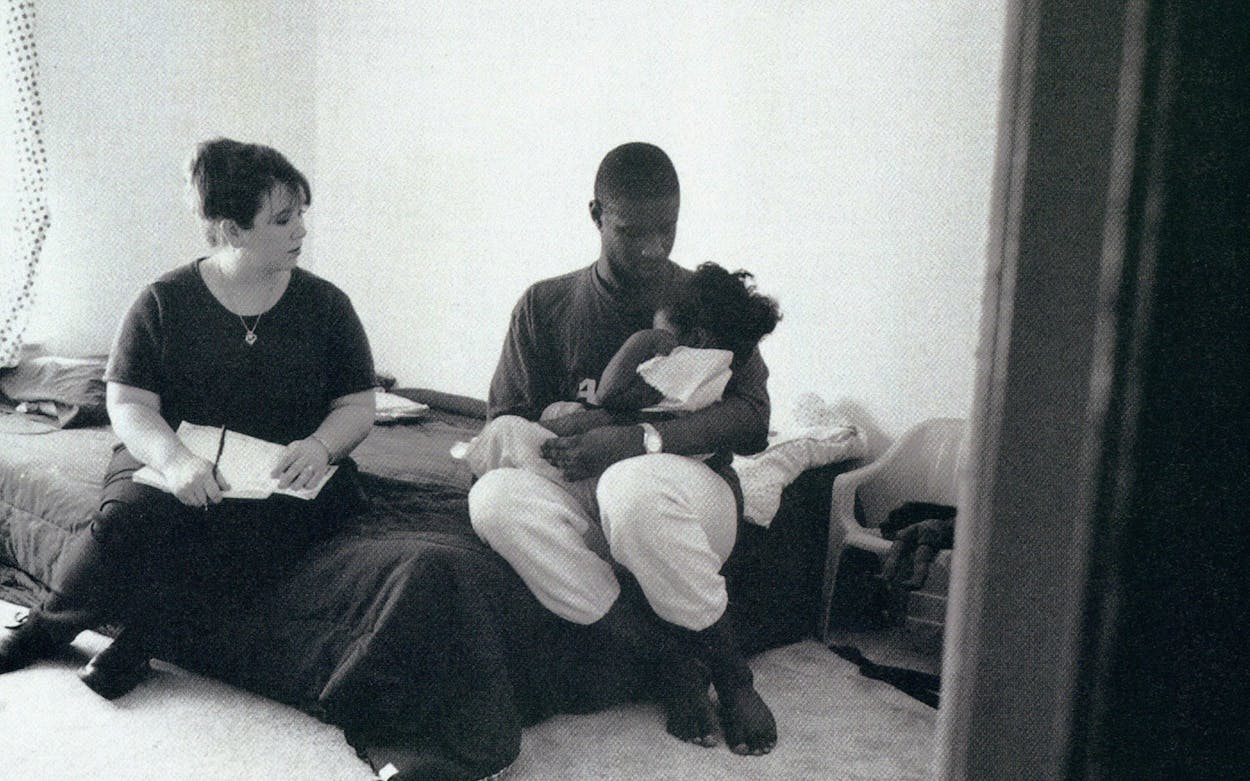

“Something’s going to happen to that one,” she had told another Unit 25 investigator, 24-year-old Reneé Munn, who also had more than forty open cases. Reneé was the staff sentimentalist: On the walls of her office were photos of kids she’d tried to help, including one of four beautiful young sisters who were sexually abused by a relative. She had come to work that morning hoping to find time to talk to five children from a middle-class Austin family who kept showing up at school with bruises and welts on their legs. But Randy had quickly handed her two more folders, one of which told the story of a 17-year-old who had just given birth to a girl. Nurses at an Austin hospital had called CPS to say the mother seemed mentally slow, didn’t know how to feed the baby, and was unwilling to change her diaper—and because she had no insurance and was not registered for a government aid program, the hospital had to discharge them. “Reneé, that mother needs some support services,” Randy had told her. He didn’t have to say what else was on his mind: Without supervision, the baby could easily die of neglect.

Randy thought about giving the motel case to his newest caseworker, 23-year-old Stephanie Fambro. He could tell she was a fighter. Whenever she heard him describe a gruesome case, she would narrow her eyes and angrily purse her lips. But on this day he really needed her to focus on another report that had just come in: An 8-year-old girl with bruises was hiding every afternoon in a drainage tunnel near her apartment complex, and no one knew where her mother was.

Finally, Randy handed the file to the caseworker standing on the far right of his desk. Jackie Rowe, a pretty, blue-eyed 24-year-old who had swum competitively at Ohio University, worked as a social worker in her native Kentucky for a year before moving to Austin because, as she put it, she was ready for a change of pace from her genteel life. Yet after only a few days on the job, she was already talking about how different life in Texas was for children. “How do you get to all the cases?” she had once asked her co-workers when she too found herself with a backlog of forty files. There was a long silence before someone replied, “You don’t.”

“Do the best you can on this one,” Randy said as Jackie took the folder. She twisted her lips in what looked like a smile. But Randy noticed that her shoulders were slumping, a clear sign that she was succumbing to the pressure. Jackie put the folder on top of another one—a case involving a boy in the East Austin projects who wore cotton in his ears to keep out the roaches that crawled on his bed at night—and walked out the door.

When Governor George W. Bush proposed earlier this year to allocate funds to hire 380 more CPS caseworkers, you might have thought that something was finally being done to fight child abuse in Texas. Perhaps because they didn’t want to risk alienating Bush and state legislators, CPS officials spoke out publicly in support of the plan. Newspaper editorialists applauded what they saw as a commitment by politicians to address the problems of an underfunded and understaffed agency.

What no one said, however, was that the new caseworkers would have no noticeable effect whatsoever on the safety of the state’s children. The brutal truth about abuse and neglect in Texas is that it’s escalating out of control, and recent front-page headlines—child abuse deaths increased from 103 in 1997 to a record 176 in 1998, newspapers reported in January—only tell a small part of the story. There are so many kids now being abused or neglected that the 2,631 CPS workers statewide (fewer than a third of whom work full-time in investigative units) are completely overwhelmed. Out of desperation, they’ve taken a “triage” approach to their job, much as doctors on battlefields do: Less serious wounds that would have been fully investigated five years ago (such as bruises on an older child as a result of spanking) are now ignored so that more attention can be paid to the worst cases.

In fact, of the 360,000 calls made to CPS last year reporting what was thought to be abuse or neglect, only 151,349—well under half—were considered significant enough to be labeled potential cases. (The other calls were classified as too vague to be investigated or outside the CPS definition of abuse or neglect.) Of those 151,349 calls, caseworkers only looked into 111,147. Even more disturbing, fewer than 30,000 of those 111,000 or so reports—less than 10 percent of the total number of calls—were labeled “confirmed” instances of abuse or neglect, the standard that must be met before CPS can monitor a family or remove a child from the home.

Some might suggest that the reason for this low number of full-scale investigations is that CPS is inundated with false or unfounded reports—the kind of reports, for instance, filed by parents who level child abuse allegations against their ex-spouse to win divorce or custody cases. Not so. In the past thirteen years, the number of children living in Texas has shot up by 16 percent, to 5.5 million. Of those, 1.5 million—more than 25 percent—live in poverty, which child abuse experts say is where most abuse and neglect occurs. It is no secret that rampant use of drugs like crack cocaine has also led to the greater deterioration of families. CPS reports that nearly 900,000 Texas children were at risk for abuse or neglect in 1998, a 7 percent increase over 1992.

The first warning bells about Texas’ child abuse crisis were set off last year by state district judge F. Scott McCown, who oversees many of the child-welfare cases for Austin and the rest of Travis County. While flipping through some old records, he noticed that in 1985, when the state’s child population was just under 4.8 million, CPS officially designated 62,233 children as abused or neglected. How, he wondered, could the number of children being abused have dropped from 62,233 children in 1985 to 44,536 in 1998? He then discovered that the number of potential child abuse cases assigned for investigation was also dropping steadily year after year. In 1993, 21.91 cases were investigated for every 1,000 reports made. But in 1997, only 16.93 cases were investigated per 1,000 reports. Upon further examination, McCown realized that CPS caseworkers in Texas were not removing children from abusive or neglectful environments as often as caseworkers in other states did. Texas ranked thirtieth in “removals,” taking a mere 7,723 children out of their homes—a far cry from California, which had 26,987 removals. If Texas had just raised its numbers to the national average, an additional 5,897 children would have been removed from their homes.

What was going on? How could it be that, while other states were increasing their investigations and confirming a larger percentage of cases of abuse or neglect, Texas’ CPS caseworkers were doing fewer investigations, confirming a smaller percentage of those cases, and then not removing enough children from potentially life-threatening circumstances?

The answer, of course, has to do with money. Texas ranks near the bottom of the fifty states in the amount it spends per capita for child welfare, and CPS officials are consistently told to cut their budget. Often that means cutting staff, since salaries and benefits are a particularly juicy budget line; in fact, CPS has fewer staff today than it did in 1995. The agency’s increasingly heavy workload compounds the problem. Not only is CPS charged with investigating cases, but also it is legally required to supervise all of the children it takes out of abusive homes and places in foster homes or with extended family members or close friends. In 1997 CPS was responsible for 23,595 children, nearly 15,000 more than in 1985. As a result, most of its money is spent on taking care of them, leaving less available every year to investigate the predicaments of children in need of help but outside the system. CPS is now little more than a leaky rescue boat, according to Judge McCown, “so heavily loaded with children . . . that it moves slowly to the scene of the next crisis and once there has little space for new passengers.”

What’s more, the department’s triage policy simply isn’t working, for as any CPS staffer can tell you, it’s often the smaller cases that quickly escalate into disaster. Some of the kids who are dying or showing up in emergency rooms with their bones broken have been the subjects of previous CPS investigations that were closed too early. Others are not saved because overly stressed caseworkers are starting to make mistakes. In Kingsville last June, a twelve-year-old boy was beaten to death with a belt, a hose, a board, and a rock by his father and stepmother. His body was found on the bathroom floor, covered with fire ants. The local CPS office had been informed about the allegedly abusive relationship, but as one CPS official admitted, the young caseworker who went to the house “didn’t see the bruises on the boy or have time to double-check answers or talk to other people about what they knew. He didn’t do any follow-up.”

Sadly, critics say, this is the rule rather than the exception. The policy of the state of Texas is, in effect, to put the safety of our at-risk children in the hands of young, typically inexperienced caseworkers who earn an average of $23,000 a year. And they do the most mind-numbingly difficult job imaginable, as I learned when I spent eight months following around Randy Shell’s Unit 25, one of three investigative units that cover Travis County. I wanted not only to see the kinds of challenges the unit faced but also to assess its ability—or lack thereof—to make a difference in the lives of children at risk. “There’s hardly a day that goes by that I don’t ask myself if this is the day a kid dies from my unit,” Randy told me not long after I met him. “It’s happened to me before, and I know how quickly it could happen again.”

The baby girl was lying on a white table, her bruises shining like freshly washed plums under the hospital lights. Unit 25 investigator Christine Cheshire sucked in her breath as she listened to a nurse read from a chart. The girl, fourteen months old, had a large lesion on her chin, a burn on her shoulder, three bruises on her back, one bruise on her chest between her nipples, and more bruises on her arms, thighs, and buttocks. There were lesions in the area of her vagina that could not be explained. Her left leg was fractured in two places; one of the fractures was several months old. She had sustained retinal damage in her eyes that was consistent with shaken baby syndrome. A CAT scan revealed a bleeding bruise to the brain.

“It’s amazing she’s alive,” Christine said when she called Randy Shell. She tried to keep her composure. “The mother says she thinks the baby-sitter did it, and the baby-sitter says she thinks the mother did it.”

“Anybody else saying anything?”

“Nothing.”

It was late August, one month after Randy had assigned the cases involving the crack-addicted mother in the motel, the child left outside at night with the potato chips, and the little girl hiding in the drainage ditch. When I asked him what had come of those investigations, he paused. “Sorry,” he said. “We’ve had so many cases come through here since then that I have trouble remembering all of them.”

As it turned out, they’d been lucky in July. After two full days of searching, caseworker Jackie Rowe had finally found the motel where the mother was staying and persuaded her to let CPS move her two children to their grandmother’s home. “But to tell you the truth,” Jackie told me, “it’s probably going to be a matter of days before the mother realizes that CPS has filed away her case and goes back and gets her kids. And then, eventually, one of us will get another report about her.”

To help the teenage mother who was about to be released from the hospital with no clear idea how to care for her newborn, Randy had called his longtime contacts at other county agencies and arranged for social workers to be brought in to watch over the child. Still, on her off days, caseworker Reneé Munn was dropping by the house, just to say hello. “In a few weeks the social workers are going to leave that mother with the baby,” Reneé said, “and she is going be alone with that child.”

“And then what?” I asked.

“We have to cross our fingers and hope for the best.”

As for the girl in the drainage ditch, Stephanie Fambro tracked down the girl’s mother—she was in a tattoo parlor—then pointed her finger at her and told her to find relatives who would keep the child after school.

And Christine’s case of the two young sisters, one of whom had cigarette burns? She was able to get the courts to temporarily remove them from their home until the parents had gone through CPS-sponsored counseling (a three-hour session with a psychologist) and a series of parenting- skills classes. She had found the girls space in the usually packed Austin Children’s Shelter, which provides living quarters for abused kids who have no other place to go, and for a few minutes, before heading off to another case, she had sat with them in the kitchen of the shelter, watching them eat sliced peaches. They kept putting down their spoons and smiling at her. “Sometimes you try to tell yourself it’s all worth it, you know?” Christine said that week. “You think that, just maybe, you did something to make their lives a little better.”

But now, a month later, standing at the hospital alongside a child who was nearly dead, Christine was in a daze. No matter how many hours a day she spent at her job, she still could not comprehend why an adult would deliberately hurt a child. Even if the mother wasn’t abusing her daughter, she surely had to have known for months that someone else was. “This is one of those cases where you ought to be able to go to a judge, tell him the facts, and get that child to a family who will love her,” Christine said.

Yet she couldn’t. Instead, she had to go back to work and prepare an affidavit asking a judge to remove the child from her mother’s home. Pulling together the twenty pages of paperwork would take the rest of the day and much of the night, putting her farther behind on her other cases. Even then, she knew that there was a good chance the mother would get the child back. Since Christine had found no hard evidence suggesting the mother was the abuser—the child was, of course, too young to give a statement—the mother could easily challenge the affidavit. It was a scene that played out over and over at the child welfare courtroom in downtown Austin: a parent tearfully proclaiming his or her innocence before a judge, then lambasting CPS caseworkers as storm troopers with a license to rip apart families.

Back at the office, other caseworkers were immersed in new cases of their own. A toddler with gums that were bleeding from forced feedings. A three-year-old boy seen holding a marijuana cigarette. A thirteen-year-old girl, mentally unbalanced since her stepfather shot her in the head when she was four, living on the streets because her mother said she could no longer care for her. When I told Christine that the Child Welfare League of America recommends that a caseworker handle just twelve cases at any one time, she laughed. “Where did that number come from?” she asked. “Fantasyland?” In the investigative units in Texas’ urban areas, caseworkers rarely have fewer than forty cases going at once. “Unless you are willing to be here all day and all night and on weekends,” Randy said, “you will never have time to build a relationship with these families, some of whom really would like some help. You don’t get the chance to prevent fires. You’re lucky if you’re able to put a few out before they burn out of control.”

As opposed to the typical CPS staffer who receives a college degree in social work and comes straight to the agency, Randy began his career as a Chinese linguist with the Air Force. When he left the service in 1990, he could have made a nice living as a national security consultant, but instead he joined CPS’s Austin office as a caseworker. “Nothing sounded more heroic than rescuing abused children,” he told me. He quickly learned, however, that there were few chances to be a hero. In one of his first cases, he went to the hospital to look at a baby who had been shaken so badly by the father that his brain was disconnected from his spine. Randy held the baby’s hand as a nurse turned off the life-support machine.

A few years after arriving at the agency, he realized that all 24 people who had been in his training classes had resigned. Many quit out of exhaustion or because of the extraordinarily low pay. Some quit because they kept waking up in the middle of the night, terrified that a kid in one of the cases they didn’t have time to investigate would turn up dead. “They didn’t want blood on their hands,” Randy said. “Who could blame them?”

But Randy stayed. He bought a rusty school bus, towed it to a piece of land he owned outside of Austin, and converted it into a home for himself. He purchased a beat-up Mercedes that often broke down but had a back seat that was big enough to accommodate several kids at once. Although many abused children hid under beds or ran from their homes when they saw him tooling through their neighborhoods—their parents had told them CPS wanted to put them in prison—Randy kept coming back around. After he removed his first three kids—he got a court order to take them from their mother, an aging prostitute who was reportedly trying to sell them to her johns—he became so attached to them that he looked them up each Christmas thereafter and gave them presents.

In July 1996, after working in a CPS conservatorship unit (a group that watches over kids who have been removed from their homes), Randy was named the supervisor of Unit 25. Waves of new caseworkers were put in his charge, and he tried to teach each one everything he knew: how to stay calm when listening to threats from parents, how to avoid gasping when a child began reciting the litany of ways he’d been kicked or punched, how to let a child know quietly that nothing he’d done was deserving of such punishment. He made a point of going on calls with the new caseworkers, making sure they looked in refrigerators to see if there was food and ran their fingers through the ashtrays to see if there was any marijuana or crack. He insisted that his caseworkers have cute stuffed animals in their offices so that visiting children could have something to play with, and he provided them with anatomically correct dolls that could be handed to a child to learn whether someone had touched him in a “good place” or a “bad place.” He stopped taking vacations. He worked on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. He started spending nights at the office.

And yet the cases kept coming. By 1998 Travis County was leading all other Texas counties with 9.5 cases of reported child abuse and neglect for every one thousand children—second-place Bexar County had 8.1 cases—and more kids were slipping through the cracks. In the fall of 1997 Randy received a phone call from a caseworker at a dilapidated house less than a mile from the state capitol. Inside was a nine-year-old girl named Victoria. She apparently had been living in a single room and had never once ventured outside. Her clothes were stained with feces. She urinated on the floor and, as a cat does, attempted to cover it up. She had no language skills; she only made squeaking sounds, imitating the rats that climbed around the windows of her room and rustled underneath the piles of trash on the floor.

Randy did some checking and learned that CPS had received its first phone call about Victoria in December 1994. Yet the report was never assigned to a caseworker because the information was too “vague.” After two more referrals about the girl in 1995, it was turned over to another unit. An investigator made quick visits to the home but did no follow-up after the mother assured him the girl was mentally retarded and was being homeschooled. Not long afterward, that caseworker quit the agency for another job, and the manila folder containing details of Victoria’s life of squalor went untouched for more than two years. Only when another complaint came in did the case get the attention it deserved.

Around the same time, a two-month-old baby boy named Nakia was found dead in his crib in another ramshackle, trash-filled Austin house overrun with rats and roaches. The baby had died from a respiratory infection that was possibly caused by rat feces. His mother was just seventeen years old, and she was living with her own mother and her seven younger brothers and sisters. Randy was devastated when he found out. The family had been the subject of ten CPS investigations between June 1994—more than three years before Nakia was born—and February 1997. The last time, a just-hired caseworker had gone to the house to look into reports of physical and medical neglect of the children, but he had closed the case after the adult mother promised to fix the broken stove, clean the refrigerator, where roaches were nesting, and get rid of the rats. It never happened. “The hardest thing for a new caseworker is to decide whether children should be removed from a home where there is no abuse,” said Randy. “No matter how impoverished the home life is, it’s still home for those kids, and you know that moving them out and putting them in foster care will scar them forever. On the other hand, if you give a neglectful parent too many chances, those kids will be scarred in another way altogether. In this job, you can feel damned if you do and damned if you don’t.”

Predictably, it didn’t take too long for most of Randy’s caseworkers from that period to resign or transfer to other CPS jobs. The woman who had handled Victoria’s case was so shocked by what she had seen that she quit working with children and moved to Chicago. Replacements arrived, though not much changed: One lasted only a day.

But when Christine, Reneé, Jackie, Stephanie, and others arrived in late 1997 and early 1998, Randy thought he had finally turned a corner. They were willing to do whatever it took to protect kids. On her own, Stephanie marched up to a crack dealer’s house and demanded to see a mother who supposedly was living there with three unfed, unclothed children. “Get off my f—ing property or I’ll kick your ass,” the crack dealer told her. The mother quickly moved to another crack house, but Stephanie found her, showed up with the police, and got the children removed.

By last November, however, Randy could sense the dynamic shifting. His staff had grown tired of writing up the notes from all their investigations, especially those that turned out to be false reports. They resented having to spend all day standing outside a courtroom waiting for a hearing, only to have lawyers postpone it for another week. They hated having to work holidays, when parents were more likely to be home drinking and losing patience with their kids. And they were sickened by seeing so many child abusers getting off scot-free. Randy himself knew the feeling all too well. Once, he had worked on a case in which a father had beaten his child to a bloody pulp, then drop-kicked him into a wall and stuffed him between pillows. But because there was no corroborating evidence—as in many cases, the wife and children were too scared to testify against him—the father was never prosecuted. A few years later, the father was riding his bicycle when he was accidentally hit by a truck and killed. Randy and his CPS colleagues could barely keep from hugging one another when they heard the news.

In January, after a difficult month in which more than 550 cases were assigned to just three investigative units in Travis County, Jackie Rowe quit. She had not been able to sleep at night, she said. When she closed her eyes, she would see the faces of children. She would lie in bed wondering about kids she’d not been able to visit that day. When Randy asked her what she would do next, she said, “I don’t know. I’m just leaving.”

Jackie’s co-workers openly admitted that they were jealous. While sitting in Reneé’s office one afternoon, Christine said, “Every morning when I open the newspaper, I look for the stories about dead children to see if one of them was mine. I want to know what it feels like to get up in the mornings and not have to worry.” In the last six months of 1998 Christine had gained 25 pounds. Instead of Carson McCullers, she had taken to reading Sylvia Plath. She had begun scouring online classified ads for another job. “Sometimes when I’m alone in my office around all my files,” she told me, “I shut the door and put my head down on my desk, and I try not to cry.”

But Christine was not the next to go. In early February Randy gathered his staff around his desk and told them he had been chosen to manage a statewide program that would set up contracts with organizations to provide more services to children, such as runaway shelters and outreach programs. The money was a little better—after eight years at CPS, he was making only $34,000 a year—but the real reason he was leaving, he said, was because he too was overwhelmed. His caseworkers stared at him open-mouthed. Soon, other workers from around the building were coming over to Randy’s office to ask if the news was true. They told him that he couldn’t leave: He was the only investigative supervisor with more than a few months of supervisory experience. “I just need to take a break,” he told me that day. “Whenever I’ve tried to take a vacation, I spend all day on the phone talking to caseworkers who need help.”

He paused for several seconds. “Maybe I’ll come back. Maybe I will. But, God, I’ve never felt so weary. I’m having a hard time giving my old pep talks to the caseworkers about how they are making a difference. I just gave Christine a case about a father carving 666 in his chest, bleeding on his own six-year-old daughter, and then taking her to a funeral home to dance in a fountain. And here’s another one about a three-year-old girl from Honduras who’s been abandoned here. She’s dying of AIDS. She’ll die alone somewhere, wondering where her mommy is.”

As it happened, Randy barely had time to say his good-byes. In his last days on the job, he had new cases to assign and a new caseworker to train: Ambrose “A.J.” Jones, a bright 33-year-old who was hired to take Jackie’s place. Like Randy, A.J. had been in the military—in his case, the U.S. Navy. After his time in the service, he returned to college to get a degree in social work. He joined CPS, he told me, “because I wanted other children to know they felt protected, the same way my own seven-year-old son feels.”

On February 11 A.J. left the office to look into a report that a young boy was being neglected at a shabby home in South Austin. Randy decided to go with him, and as he read over the initial report, he recognized the name of the nineteen-year-old father. When the father had been a boy himself, Randy had removed him from his home after discovering that his parents were neglecting him. “It’s amazing the way this cycle works,” Randy said. “The kids I once tried to help are now the parents I’m having to investigate. Maybe I have been in this business too long.”

The house smelled like sewage and dogs and rotting food. The floor was covered with tops from old vegetable cans, soiled magazines, old clothes, beer bottles, and cigarette butts. The broken toilet was full of feces, the bathtub half full of brown water and garbage. The stove had been ripped from the kitchen wall. The father was gone—he had moved out days before—but sleeping in the house were two young men in punk outfits who, Randy guessed, spent their days begging for money along the University of Texas Drag. A.J. and Randy went into a front bedroom and saw a two-year-old boy with dirt on his feet and hands lying on a bare mattress. The boy’s mother, wearing overalls and a tank top, was sitting beside him. She had clearly not bathed in a long time: There was a ring of dirt around her neck. Both she and the boy sounded congested.

A.J. did the initial questioning. The mother told him that she was doing her best with her son. She said she had taken him to the doctor—and, indeed, she showed A.J. the medicine she had been given for the boy’s cough. “I love my child,” she said. “I do everything I can for him. Do you want to punish me just because I’m poor?” As filthy as the house was, A.J. had to admit that he’d seen worse. He also had met parents who were far more neglectful and who never would have gone to the trouble to get medicine for their sick children. He decided to give the mother a stern warning about the condition of the house. He was going to leave the boy in her care, but he would return in a few days to see how things looked.

But after studying the medicine bottle himself, Randy took A.J. outside and said, “We’re removing the child. The mom’s not giving the child the proper dosage of medicine. She should have finished this bottle by now. There’s no telling how sick this kid is.” A.J. stared at Randy. He had not even thought of checking the medicine. “It’s all right,” Randy said. “You only learn this stuff from experience.”

When Randy told the mother they were taking the boy with them and getting a court order to keep him until the house was no longer a health hazard, the mother began screaming, “No! No!”

“What gives you the right to play God, you motherf—er?” one of the young punks shouted at Randy. “I bet your place looks like shit too!”

For several minutes, the mother wouldn’t let go of the boy. Neighbors surrounded Randy and A.J. and insisted that the woman didn’t mistreat her child. “Get your ass out of here,” someone shouted. “Why do you like ruining other people’s lives?”

When Randy finally got the boy out of his mother’s arms, she collapsed and began sobbing uncontrollably. Randy and A.J. then drove him to the emergency room, where doctors discovered that he had severe bronchitis, infections in both ears, and a temperature of 103.7.

“If I had left him at the house, he could have died that day,” a visibly shaken A.J. told Randy that night. At first Randy said nothing; then he told A.J. to go home and get some sleep. But A.J. didn’t sleep a wink. He lay awake in bed, wondering if he would be able to last a year on the job.

A few days later, Randy’s colleagues gathered at a nearby restaurant for his good-bye party. Everyone was determined not to talk about work, but within fifteen minutes the air was thick with stories about the latest CPS investigations. Christine came with her new boyfriend, an Austin police officer she’d met while working on a case. “Where else does a CPS worker meet someone?” she asked me. A.J. sat quietly at another table and left early. Reneé sipped cocktails with a couple of CPS staffers who used to work for Randy. (“I’m staying,” she was overheard murmuring. Although she and Christine had quietly put in for transfers soon after learning of Randy’s resignation, they had made a pact to remain with Unit 25 until the fall of 1999 so that they could say they had lasted two years.) Most of the group didn’t go home until around midnight. Randy, one of the last to leave, said he was going to take a long-deserved three-day vacation before starting his new job.

But the next morning, he slipped back into his old office. It was a Saturday. No one else was there. He began to pack his things, but then he saw some manila folders on his desk. He stopped what he was doing, flipped open the top one, and started reading. “I just want to make sure no one is slipping through the cracks,” he said.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- Austin