This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

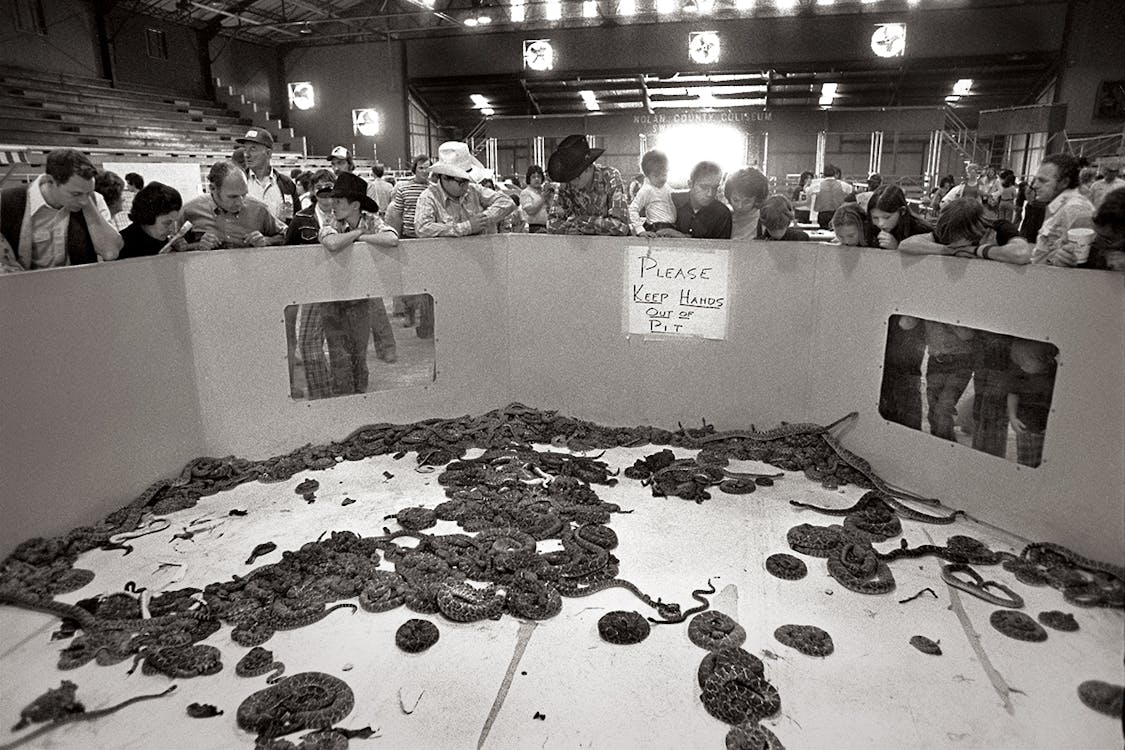

Several hours before the 1976 Rattlesnake Roundup is officially to begin, two Jaycees in red felt vests and red-white-and-blue baseball caps cross the floor of the Nolan County Coliseum. Between them they carry a metal garbage can that is so heavily loaded they can barely skim it above the ground. When the Jaycees reach a white octagonal stockade they take the lid off the can, heft it over the chest-high plywood wall, and turn it upside down. I don’t suppose I have to tell you what comes out.

There is already a great braided mass of rattlesnakes inside the pit—the first early fruits of this year’s Roundup—and when the new arrivals land in a knotted clump on top of them the air is enlivened for a moment with the chilling whirr of several dozen sets of rattles. The snakes try to coil but they are so entwined that few of them manage it, so the majority simply swing open their jaws and hiss, displaying the long cuticular sheaths of their fangs and the pink satiny inseam of their mouths.

The Sweetwater Rattlesnake Roundup, it is said, is the biggest rattlesnake roundup in the world. It is said, of course, mostly by the Sweetwater Jaycees, who are responsible for mounting the event every year. There are vague rumors that one roundup in Oklahoma is really larger, but since I have the flu and consider my presence here already above and beyond the call, I won’t track these rumors down.

It might be useful, though, to explain exactly what a rattlesnake roundup is. It is an event in which people, individually and in groups, scour the countryside and capture great masses of live rattlesnakes, chop their heads off with machetes, and eat them. Essentially.

For the masses, and they do amass, it is a chance to look down into a pit filled with hundreds of rattlesnakes and let certain primal fears out for a romp. Spectators can watch snakes being milked, poked at, and slung around, they can attend the Miss Snake Charmer beauty contest, buy a clear plastic toilet seat with a twelve-inch rattlesnake sealed into the lid, and end their rattlesnake glut quite appropriately as a contestant in the rattlesnake-eating contest.

All this is scheduled to begin at ten o’clock this Friday morning. The Jaycees are bustling about with their bushels of rattlesnakes like anxious parents hiding Easter eggs for their kids. Another load of disgruntled reptiles is slung into the pit. The snakes calm down somewhat after the newcomers have had time to absorb the shock and confusion of their arrival. A few of them begin to glide in a soft, straightforward crawl over the lethargic bodies of the more settled occupants. Others try to scale the low wall, but their ventral scutes cannot afford them the vertical traction they need to reach higher than the plastic viewing windows a foot or so from the floor.

I bend down to look through one of these windows and find myself staring into the alien countenance of a rattler that is swaying back and forth like a cobra. Like all the others in the pit, it is a western diamondback rattlesnake, Crotalus (for “castanets”) atrox (for “fearful”). This individual is perhaps three feet long, a good deal smaller than the seven-foot record holder, but certainly capable of assuming gargantuan proportions if confronted in the wild.

The snake’s head is broad and flat, with venomous jowls and two close-set eyes that seem fixed and vestigial. Dusky geometries, interlocking diamond patterns that look like sand paintings, lead down to the still rattle, the hard hollow conjoined nubs of keratin left behind by moulted skins. An English explorer reported in 1714 that at the sound of this instrument inhabitants of the New World were “seized with sorrow.”

The snakes gravitate toward the sides of the pit, leaving a clearing in the center furnished by a small table, upon which a small glass sits supported in a vise. As I move back from the enclosure the individual rattlers seem to meld into one of those deadly organic forces that in horror movies tend to seep under doors and well up in moist crevices, twitching and foaming and waiting impersonally for a victim.

That’s a pretty distasteful metaphor, and the fact that I’ve concocted it dashes my hopes for the cool-headed appreciation of our slithering brethren that I’d hoped to present. But, like everyone else in our culture, I was inculcated with a fear of snakes at an early age. The greater part of my education was conducted under the outspread arms of a plaster Virgin Mary whose bare feet were invariably scrunching the arch-fiend himself in the guise of a serpent.

You don’t sit under such a display for a good many formative years without feeling the compulsion to choose up sides. What’ll it be, kid, the Virgin or the Viper? It seemed obvious to me that God had created snakes for no other reason than to watch them squirm and stew in their own self-loathing, that indeed He probably spent His off-hours in heaven hacking them to pieces with a hoe. It would not occur to me for a long time that maybe snakes were, after all, a legitimate form of life.

But standing here before a pit full of rattlers early in the morning is not helping to dispel my conditioning. I go out into the parking lot, where a small group of prospective snake hunters are idly passing the time waiting for registration to begin. A cowboy with a well-pruned mustache and a snakeskin hatband is leaning against the hood of his Scout and picking imaginary rattlers up off the concrete with his homemade snake tongs. A group of longhaired factory workers from Houston who have driven all night stand around in the cold air goosing one another and exhausting their repertoire of disreputable snake jokes. A man in a lime-green leisure suit and a pompadour walks around the parking lot like a sleepwalker.

I fall into conversation with a morose-looking accountant from Chicago. As he speaks he runs his thumb along the blade of an enormous cheap Bowie knife whose empty scabbard hangs from his belt almost to his knee.

“I’ve been waiting for this for years,” he says. “I’ve seen rattlesnakes in zoos and on TV and I just couldn’t stand it anymore, I just had to come down here and catch one.

“I’ll do every crazy thing you can think of. Most people wouldn’t go into a pit with a bunch of rattlesnakes, but if they gave me the chance I’d do it. Next thing I want to do is go shark fishing with a spear gun, and then I’m going to go hunt grizzly bear with this old flintlock rifle I have. That way the bear’ll have a fighting chance.”

He puts his knife away and looks off at the prairie on the other side of the coliseum. “I don’t know what it is that makes me do things like this. I guess it’s just my sense of adventure.”

By 10 a.m. the roundup has, without fanfare, officially begun. Most of the early hunters have already paid their $5 fee at the registration booth in back of the coliseum. This fee buys them a map of the official hunting areas (which are local ranches involved in a symbiotic relationship with the Jaycees), a red ID ribbon, and the opportunity to compete for any of a dozen trophies.

The filing fee also includes an optional chaperoned safari to the hunting’ areas, since the Jaycees have learned from experience that a great many of the hunters haven’t the slightest idea of where or how to catch a rattlesnake. To assuage this ignorance, the registration table is laden with items for sale: snake tongs for $25 apiece, $6 snake hooks made from recycled golf clubs, squirt cans for gassing the serpent from his lair and official Bicentennial Rattlesnake Roundup caps. A man from Arizona buys one of everything and sets his boxed snake tongs in the crook of his arm.

I join up with a caravan headed out to the allegedly snake-infested prairie. A hunter from Dallas named Ken Schroeder hitches a ride in my car. He carries a long broom handle with at loop of wire at one end that can be closed from the handle once the head of a hypothetical rattler is hypothetically inside. He made the snare himself, and it differs considerably from the official tongs that the Jaycees are selling. These are shaped like spear guns and feature three mechanical prongs that are operated by a trigger in the handle. In the off-season they probably double as barbecue tools.

“I sure hope this works,” Schroeder says, cramming the snare into the car. “I’m really counting on catching a snake.”

“Uh, why?”

“I don’t know. It’s just something different to do. Everybody in the office thought I was crazy when I told them I was coming down here. I started to wonder if maybe I didn’t have some weird homosexual tendencies or something for wanting to do this. But I was raised on a farm, you know, and I’m interested in animals, and this is one animal I’ve never had any contact with.”

He wears a high bulbous cowboy hat that reaches up to the ceiling of the car, a piece of headgear so inconsistent with the prim set of his face that it looks like something that has taken up residence on his head without his knowledge.

Schroeder looks wistfully out the window at a Dairy Queen sign that says “Welcome Snake Hunters.” He wears a high bulbous cowboy hat that reaches up to the ceiling of the car, a piece of headgear so inconsistent with the prim set of his face that it looks like something that has taken up residence on his head without his knowledge.

The Double Heart Ranch, our destination, is located five or six miles from the Sweetwater city limits. It is still midmorning when our caravan drives past the big seven-foot Valentine hearts that mark the graves of the husband and wife who once lived here. There is a desert clarity to the sunlight, and beneath it the dry broomweed carpet is the color of wheat. Off to the west we can see the land drifting away into the vast unmarked expanse of the Llano Estacado.

We drive down a dirt road that leads away from the hearts and runs perpendicular to a series of draws forested with scrub cedar. Once we are out of our cars, Wes Ronemus, one of the four Jaycee bwanas, assumes some high ground and delivers an orientation lecture. We’re told all the standard precautions: stay alert, watch your step, keep your noses out of snake dens. If we hear the rattle of a snake we should freeze, since sudden motions are to a rattler a sign of bad faith.

As he speaks, Ronemus picks up rocks with his snake tongs and slings them aside. The hunting party listens impatiently. It consists of about 30 people, few of whom are armed with any sort of snake-handling device. There is an elderly couple from Colorado, an adolescent cowboy with a fistful of snuff mouldering in his cheek, two men wearing identical blue jumpsuits, and a number of individuals like Schroeder and the knife-wielding accountant who seem simply to have a calm resolve to catch a rattlesnake and go home.

When at length we descend into the draw, the group splits roughly into four patrols that form behind each of the Jaycees. I follow Ronemus along a path that leads into a small gully formed from the cleavage of a rock face, and proceed with what I consider a rather keen vigilance, a woodland skill I involuntarily developed after a sixth-grade picnic at which I unexpectedly came across a huge coiled rattler that was trollishly guarding a dry creekbed.

So I tread today over suspicious snake haunts with an exaggerated caution that is probably not as appropriate to the business at hand as I want to think. My stealthiness, after all, has been custom-designed over the years as a way to avoid snakes altogether, and I have to keep reminding myself that we’re here to flush them out.

If-You-See-One-Kill-It is the operable and universal ethos when it comes to rattlesnakes. When the Roundup began in 1958 it was not conceived simply as a community festival or a totemic ritual, but as a way of reducing the population of one of Sweetwater’s most bounteous and least desirable commodities. This hatred of rattlesnakes has doubtless been with us ever since the European mind, still reeling from the loss of Eden, took possession of the New World and put rattlesnakes under the aegis of a new cosmology. Indians recognized the virulence of rattlesnakes as a power, but the white race, living out its own myths, could see it only as a profanity, the thorniest abomination in the Promised Land. The rattler became the ultimate varmint.

The fact that rattlesnakes will be killed here in Sweetwater in such numbers and with such relish is evidence that this tradition has been handed down to us virtually intact. Perhaps we could attribute this to some kind of racial memory, to the accumulated fears of generations of people whose lives were hard enough without losing livestock and loved ones to snakes. Tornadoes, pestilence, sandstorms, drought—the early citizens of Sweetwater could do little about such elemental catastrophes, but a rattlesnake was a finite thing, capable of being killed, and it was surely grim and grisly and dangerous enough to seem the incarnation of every counterproductive natural force. While its human counterparts were busy scratching out a New Eden, it had made its home in hell. So the rattlesnake was the prairie succubus, it carried in its venom sacs the distillate of all the poisons that plagued human habitation in the West.

It is indisputably true that many people have died or have lost limbs through encounters with rattlers. (The latest statistics indicate that 7000 people are bitten by venomous snakes in the U.S. every year, and that 14 or 15 of them die.) A good many snakebite victims, though, would not have been bitten at all had they not felt compelled to go out of their way to kill or harass the snake in question. A western diamondback is a fierce rattler, with a severely toxic venom, but it is no match for human beings and does not customarily attempt to consume them. That rattle is not, as popularly assumed, a device for the sinister but sporting reptile to warn its victims of its intentions, but a way of stalling for time while it makes its getaway.

Heedless of any such revisionist attitudes, the hunters storm through the low-lying branches, flinging limbs back into each other’s midsections, and hack their way through the cedar thickets looking for a cool, promising den. Every so often one of them will stop and remain poised for a second like a frightened deer, listening to an imaginary rattle.

The chances are slim that anyone on this expedition will spot an isolated, exposed rattler. Though the sun is still high and it’s mid-March, there is an unseasonable chill in the air. The snakes, whose blood, like that of all reptiles, adapts to the prevailing temperature, have more than likely retired to their dens rather than take on the outdoors climate.

So the object of the hunt is to look for burrows dug beneath trees, or for wide seams in the rock ledges, or for shallow caves. A rattlesnake is hardly equipped to dig its own den, so it either takes over an abandoned shelter or ingests the tenants of an occupied one. Inside these dens, snakes tend to gather for their annual hibernation festivities, and so it’s not unusual to hear of a prominent den that once yielded upwards of a hundred rattlesnakes.

“See those bushes right there in front of that rock ledge?” Ronemus says. “Ten to one there’s a snake in there.”

He climbs up to a small den tucked beneath an outcropping of rock and takes a small hand mirror from his pocket. The reflected light reveals the interior of the den in precise slivers of illumination that resemble cats’ eyes peering from the darkness. There is no snake there.

“Well, we’ll find one soon enough if we keep lookin’.”

We never do. By noon a dragnet of several hours’ duration has turned up no reptiles of any sort. The snakes have apparently adjourned from the field. I watch the gradual spread of disappointment on the faces of the hunters as they come to realize that the Texas prairie is not exactly the scalp of Medusa.

One theory, put forth by a Jaycee wearing metal leggings that look like the bottom half of a suit of armor, proposes that a mild winter has coaxed the rattlers out and afield of their ancestral dens sooner than usual, and this sudden cold snap has temporarily resettled them.

Another, more obvious theory is that Sweetwater is headed toward the Last Roundup, that the annual purge has, to use an apt metaphor, begun to swallow its tail. Ronemus notes that in the first year of the Roundup, nearly twenty years ago, 14,000 pounds of snakes were taken. Last year the total was down to 3000 pounds. This estimate is at variance with official figures, but there is no doubt the event is successful in its purpose of dispatching as many snakes as possible. Rattlesnakes are such a dwindling resource, in fact, that several roundups in other cities have made arrangements to buy their snakes from other areas. The Sweetwater Jaycees maintain that they stay apart from this practice.

It’s past lunchtime now, and the Jaycees are hungry, so we climb back up the draw to our cars. The group will return after lunch (without me) and spend the rest of the afternoon scouring the other designated areas where their efforts will be rewarded, sort of. Eight carloads of hunters will return with one snake of average size.

I have a corndog for lunch at the Dairy Queen. This seems a reasonable approximation of fried rattlesnake, which my system refuses to cry out for but which I feel duty-bound, at some point, to force upon it.

Returning to the coliseum, peopled now with the rather spotty Friday afternoon crowd, I find myself struck with a peculiar combination of odors, the smell of cotton candy and rattlesnakes. The snake population at the milking pit has remained somewhat stable, and I notice that the Jaycees are not only delivering snakes to the pit but also taking them away as well. The milking area, therefore, is only one station on a rattlesnake disassembly line. The creatures are weighed in and categorized at the back of the coliseum, taken to the milking pit where their venom is collected in the glass on the table (no one is milking them at the moment), and then transferred to the skinning booth, where they are rendered suitable for the deep-frying vats at the concession areas.

It is the skinning booth that, at the moment, is commanding the attention of most of the spectators. In this area four men and boys in blood-stained white lab coats are pulling out the entrails and tearing off the skins of headless shakes that hang from a clothesline before them. The muscles in the snakes’ bodies are still alive and ungovernable, and the carcasses contort so wildly that occasionally the butchers have to back off from their work to avoid being whacked in the face.

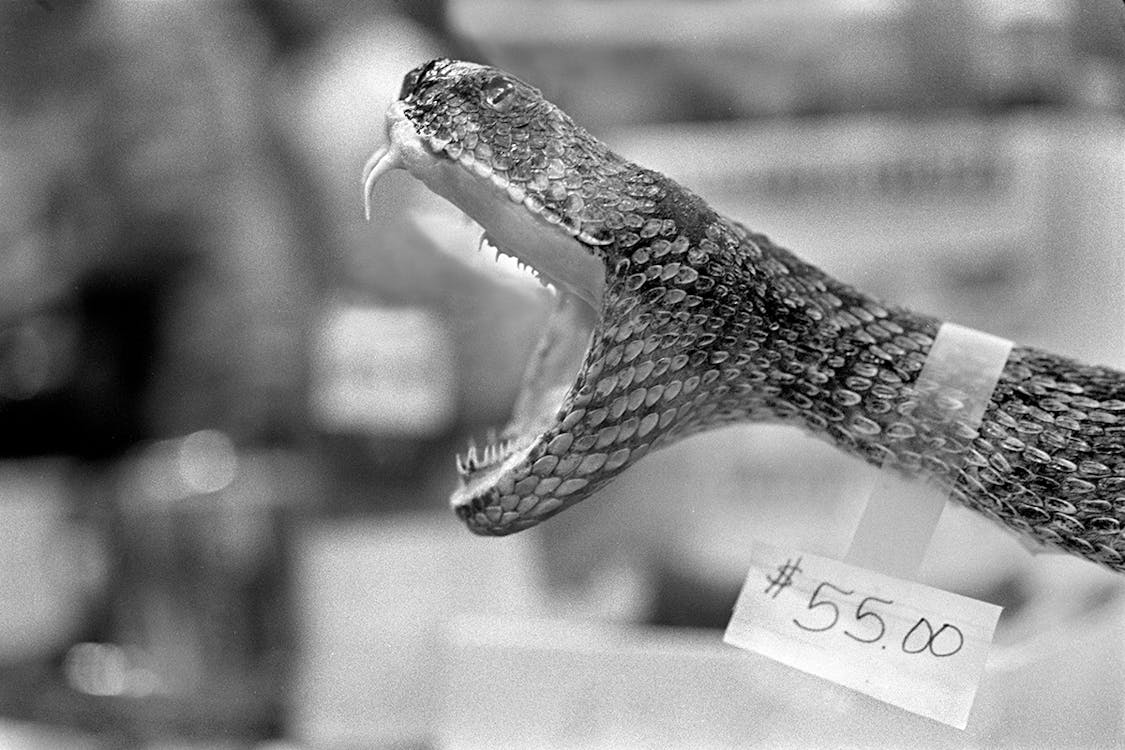

Two Jaycees in the same booth have just lifted a big rattler out of a garbage can with their tongs and have spread it out across a chopping block, A third Jaycee cuts its head off with a machete. The snake’s rattle ceases instantly, like a broken electrical circuit, and its mouth gapes into full striking position, taking on an expression that suggests forbearance pushed beyond its limits. But it is too late, of course, for the snake to act. The Jaycees throw its head into a cardboard box and toss its body at the feet of the skinners.

The undirected, stored-up, wandering impulses in the greater end of the reptile’s body try to work together one last time; the headless snake coils and rears, but the synaptic gap is too great between it and the head painfully working its jaws in the box five feet away. The data, the order to strike, cannot get through. The snake lingers hesitantly in the air, and then collapses.

“Daddy,” a little girl says in a calm, clammy voice, “I saw the rattlesnake’s head get cut off. And it’s still alive.”

Another pit in the center of the coliseum floor contains, among other snakes, the sole contender so far for largest rattler: a torpid five-footer with a band of masking tape constricting its thick body. This pit is not nearly as full as it will become in the next two days, but there must be 70 or 80 snakes in it already. Maybe one or two of these have been brought in by freelancers like the members of the group I was out with this morning. The rest were captured over a period of months by local “snake clubs” who, like all the registered hunters, sell their snakes to the Jaycees for 55 cents a pound. That’s today’s price: a rattlesnake depreciates in value approximately 20 cents a day as the Roundup progresses. This price scale is to insure that enough snakes are on hand for the early oglers.

This year, though, the Jaycees have been outbid. A thousand pounds of rattlesnake captured by a local club was bought by a private Dallas collector a few days before the Roundup opened for $1 a pound. But even with the serpent shortage the Jaycees should do all right financially. Snake meat and rattles are selling briskly, snake venom is still in demand by laboratories, and this year brings a bullish market on snakeheads. It seems someone in Alabama has discovered that bleached rattler skulls make lovely bolo tie slides and wants to buy the Jaycees’ entire grisly inventory.

A man standing next to me at the edge of the pit points to a small rattlesnake wrapped through the coils of a snake twenty times its size.

“Heh, heh. You know, it just tickles me to see that little snake snuggled up against that big feller there. That’s cute as hell.”

Bill Ransberger takes out a can of air freshener and sprays it over the rattlesnakes that encircle him inside the milking pit

“It gets kind of rank in here sometimes,” he explains as a rattler takes a dose of lemon scent in the pit glands and hisses malevolently at the aerosol can.

Ransberger is a professional snake handler of some twenty years’ experience. He has an easy, inscrutable grin whose effect has certainly not been diminished by all the venom that has passed through his veins. His shirt packet sags under the weight of perhaps twenty ballpoint pens and tiparillos, and he is accoutred at every opportunity in snakeskin. All in all, he has the look of a slightly insane scoutmaster.

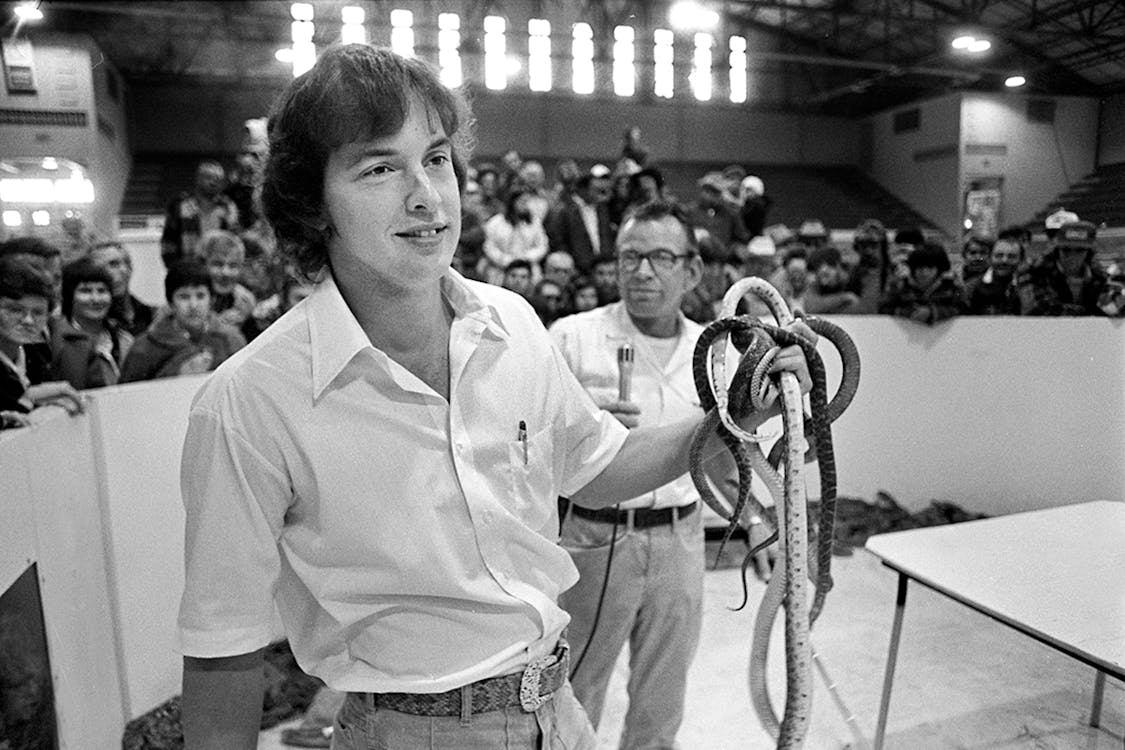

While Ransberger is deodorizing the pit, his two assistants, Larry Crosby and Clint Longley, are milking a new batch of snakes. This process is performed with an impassivity that is both boring and inspiring. Crosby grabs a big rattler at the middle of its body with his snake hook, holds it a discreet distance from himself and his fellow humans, and slings it onto the table. The rattler, made sluggish by the cool air of the coliseum, merely feigns outrage, and seems overall to have passed into some existential gloom. Crosby looks down at it with distaste, flattens its head with his hook as the rattler moves back defensively into its own coiled body, and grabs it by the back of the neck. Crosby then secures the snake’s body under his arm, hooks its fangs over the rim of the milking glass, and squeezes its head like a lemon. Something very much like lemon juice dribbles out.

Ransberger looks on with obvious pride at what he has accomplished with his students. Three years ago Crosby, who owns a chain of convenience stores in Garland, was such a herpephobe he would run from an earthworm. When he attended a rattlesnake roundup in Coleman and met Ransberger he experienced one of those peculiar occupational epiphanies that seem to be typical of snake handlers: it came to him that there was no reason to live any longer with such an irrational fear, and that the only way to rid himself of it was to get in there and mix it up with the rattlesnakes. When I ask him later what emotions he now feels toward rattlesnakes, he thinks for a moment and replies that he feels none at all.

His colleague, Clint Longley, or “Roger Staubach, Junior,” as Ransberger introduces him, is the backup quarterback for the Dallas Cowboys. He says he handles snakes because he’s a “sensationalist, a thrill seeker” and because it’s a good way to stay in the public eye during the off-season. Longley is, in that regard, an obvious asset to the snake show. He is all finesse and chummy good looks, and the crowd seems protective of his safety.

From time to time a stray snake will make a low-grade lunge at the fang-proof boots of one of the handlers, but most of the rattlers are accustomed by now to their environment and feel no threats in the careful moves of their captors.

Larry Crosby makes a slight face and throws a snake he has just pinned down into a garbage can without milking it.

“What’s the matter with that one?” Ransberger asks.

“Aw, I broke his neck.”

By this time a local sixth-grade class has filled the bleachers above the pit. Ransberger steps to the microphone and makes a few introductory remarks to the kids about rattlesnakes, admonishing them always to carry a club or a stick or something when walking outdoors so if they come across a rattlesnake they’ll have something to kill it with.

Then he announces that he will demonstrate for their benefit the striking distance of a rattler. He selects the largest specimen he can find and throws it on the table. The snake coils but is largely indifferent. Then Ransberger begins acting strangely. He runs around the table waving his arms, jabbing the snake with his hook, blowing smoke in its face. Finally the snake strikes, missing its tormentor’s shoulder by a foot.

Ransberger blows up a balloon, holds it in front of the snake’s face, and agitates the creature until it strikes the balloon and pops it. He continues this line of activity for a while. Everybody laughs at the snake’s frustrations, but there is something compelling and resolute about its behavior.

I remember from my rather scanty research how awash in perception snakes are: they can see, they can hear, they have a sense of touch and warmth, and they have extra, unimaginable dimensions: with their tongues they can gather up particles of the air and actually taste the far-flung components of their environment; and, like other pit vipers, rattlesnakes can assimilate a picture of what is immediately before them by an intricate sense of heat detection.

The snake on the table seems to be reacting to Ransberger’s harassments with the full range of these powers. The reptile’s complete absorption, its total reliance on its senses, its trust in them, seems to endow it with an overpowering integrity. The rattlesnake roundup, like most other human festivities, is inflated with hype and hoopla, but at its center, like a hard crystal, lies the irreducible awareness of its victims.

On Saturday, the second day of the Roundup, I arrive at the coliseum at noon, having awakened late in the morning with my flu symptoms intact and with my memory invested by a persistent, rather queasy dream in which I attended something called the Miss Snake Charmer 1976 Pageant.

I now realize that it was no dream. Through the gauze of my fever I can remember a stage full of knock-kneed nubiles doing the bump with one another and sort of goose-stepping around the stage to the tune of “Yankee Doodle Dandy.” I remember also a contestant whose “accomplishments” were listed as “playing volleyball and bike riding,” and I’m fairly certain I heard somebody introduced as the “1974 Yucca Duchess.” My notes, when I think to check them, reveal that I left early. There is no clue as to what I was doing there in the first place.

By coincidence, the first thing I notice today is a small, dark-haired girl with a crown on her head standing in the center of the milking pit and shrinking with trepidation as Bill Ransberger gathers up several handfuls of snakes.

“You lookin’ forward to handlin’ these snakes?” Clint Longley asks her.

“Well, sorta,” she says, almost in tears, as she takes the writhing mass into her arms. The fact that it consists of non-poisonous bull snakes does not seem to afford her much comfort. One of them, a small black number, ambles up her left arm and peers salaciously at her neck.

“Uh . . . Uh . . . ” Miss Snake Charmer says, bending her head away from the renegade snake as far as it will go.

Ransberger repositions the creature and the situation is stabilized enough for the girl to stand there with her bouquet of snakes and manage a tight smile for the photographers. I find myself grateful that I’ve never read Freud.

Finally Miss Snake Charmer, who is named Linda Tuttle in civilian life, is relieved of her snakes, and she climbs out of the pit, endures a few pats on the back, and makes for the staff trailer, where she breaks into tears.

“A very brave girl!” Ransberger comments to the crowd. Applause.

The attendance today is easily triple what it was on Friday. The snake demonstration is packed at each hourly performance, and the coliseum floor is lined with vendors’ tables laden with rattlesnake belt buckles, ashtrays, paperweights, T-shirts, even taxidermy kits for mounting rattlers.

At one of those tables I run into one of the factory workers from Houston I’d met yesterday.

“Well, we got one,” he says. “Four foot long. We got him out there in the El Camino!”

“You know how we got him? We didn’t pay no attention to those designated areas. Hell, we just drove up to the first farmhouse we saw that didn’t look like there was anybody home. We found this rattlesnake right under the porch! Listen, I’ll tell you what, you go get that photographer of yours and y’all come out to the car and I’ll kiss that snake! I’m serious, I’ll do it, right on the mouth!”

So I wander off looking for the photographer. The search proves unsuccessful, though, and I decide to break for lunch.

“I’d like an order of snake,” I tell a Jaycee at the concession stand.

“One order of snake,” he says.

For $1 I get what looks like three tiny chicken backs set in a nest of potato chips. I nibble on them a while before leaving the bones on the bleachers. What meat there is on the little random sections of vertebrae tastes like deep-fried Kleenex.

At the big blue pit I stop to observe the pile of rattlesnakes that has accumulated there since yesterday. A few of them are dead, lying on their backs with their white bellies exposed. The great majority, still alive but sluggish and ailing, move across one another in that stalking crawl that seems all at once a marvel of locomotion.

Just as I’m about to gush with latent affection for these creatures I hear the announcement for the 3 p.m. Simulated Snake Hunt. This is an entertainment the Jaycees have devised for those who have failed in their snake-hunting hopes and for those whose aspirations were never that high but who still are curious as to how it is done. Since I fall into both categories I board the ancient red and white Jaycee bus that will take us to Simulated Snake Hunt Headquarters some five miles away.

The bus requires a little tinkering under the hood before it can bestir itself, but it is soon rambling down a series of dirt roads. A minor sandstorm develops in the interior, but is not serious enough to dispel the camaraderie that has sprung up among the passengers. When finally we reach a picturesque little arroyo the driver stops the bus and opens the door.

“Y’all get off and enjoy the snakes.”

The simulators are ready for us. The Jaycees have placed a token rattlesnake on a boulder and stand in a semicircle around it like the high priests of some exotic snake worship cult. The ubiquitous Wes Ronemus is again the MC. He makes a few general remarks about a rattlesnake’s sensing apparatus, and then demonstrates how the snake on the boulder will stop rattling once we are all still.

But there are at least twenty of us, and we can never seem to stop moving at the same time, and so the snake shifts back and forth on its boulder in the direction of each new outbreak of turbulence. I don’t know what causes our restiveness, but it is surely not fear: though we are six feet away from a large, confused, testy rattlesnake, the authenticity we want to feel is rapidly on the wane.

Ronemus scoops the snake up with his hook and shoves it into a nearby rock cleft. This is the simulated den. Other Jaycees run copper tubing from a squirt can into an opening at the rear of the cleft and pump gasoline inside. By and by the snake comes out and hunkers at the mouth of the den. Ronemus picks it up with his tongs. A green fluid oozes from the snake’s anus. This is how a rattlesnake is caught.

Before putting the snake into the padlocked wooden box that reads on the outside Caution, Live Rattlesnakes, the Jaycees hold it up and invite the onlookers to feel its scales. A small boy walks up and squeezes the rattler’s middle.

“Not so hard, honey,” his mother tells him. “You’ll hurt him.”

“Naw,” Ronemus counters, “you won’t hurt him. Hell, you can kill him if you want.”

Five people are seated silently at a table, their hands clasped reverently in front of them as if they’re about to say grace. And though I wouldn’t rule out the possibility that one or two of them might actually be formulating a prayer, this is not the kind of contest you would expect God to take an active hand in.

These people are here to see who can eat the most rattlesnake in five minutes. They are undergoing an interminable countdown as the cooks prepare backup plates of snake meat and the sheriff and his deputy settle the ground rules. Miss Snake Charmer, in her official capacity, sort of presides.

“Okay, listen,” the referee tells the contestants, “the Jaycees ain’t responsible for what could happen. Snake bones in your throat, something like that. Understand?”

They nod. If they look especially solemn, it’s because the stakes are higher than you might expect: a place in the Guinness Book of World Records.

Last year Phillip Sprinkle, a slight, rather beatific-looking fifteen-year-old, ate nine pounds and three ounces of rattlesnake in something like four hours, but couldn’t officially claim the record because there was no time limit. This year he’s competing again, but because of the five-minute limit the race this time may be to the swift rather than to the capacious.

A quick check of the contestants, all male, reveals one serious contender. W. H. O’Haver, a machine-shop owner from Silsby, looks like he has emerged from the backwoods for the first time in many years for the sole purpose of calmly claiming his rightful title. He has a round, confident face, wears greasy overalls, and rests his hands, Lincoln-style, on the shoulder straps. He has already had his lunch.

Randy Eaton, another contestant, looms over his first course of rattlesnake in the exact posture of Christ at the Last Supper. I interrupt his reverie to ask him what it is he’s after here.

“Fame,” he says.

At 3:35 p.m. on Sunday, on the last day of the Sweetwater Rattlesnake Roundup, the official stopwatch is raised. The contestants’ hands hover and shake over their plates.

“Go!”

But it is no contest. O’Haver is an eating machine. He can store vast amounts of food in his cheeks like a chipmunk and swallow it all in the few seconds it takes for the judges to give him a new plate.

When it is over, Sprinkle has managed a respectable second. He looks on wistfully as Miss Snake Charmer poses with O’Haver, who sits calmly on a chair as she inserts a piece of rattlesnake into his mouth. Sprinkle accepts the condolences of his friends and goes back to work at the skinning pit.

By the time the prizes are to be awarded on Sunday evening the coliseum is almost empty. The trophies are all of the standard winged victory variety, and are given out from the reviewing stand by Clint Longley. A succession of serious-looking snake hunters step up to claim them. The Sweetwater-Snyder Hunt Club takes the prize for most snakes (914 pounds) and for largest individual (66½ inches). A man named Preston Alston caught a thirteen-inch rattler and wins the trophy for smallest snake.

I’ve been given a complimentary Roundup cap and I hold it in my hand as I stand at the milking pit and look down at the snakes one last time. My perceptions, though, are as inadequate to the situation as theirs. I can make out nothing but a pile of half-dead rattlesnakes littered with the remains of popped balloons.

During the three days of the Roundup 2397 pounds of Crotalus atrox was extracted from the landscape. Ten thousand people passed through the coliseum, 203 hunters were officially registered. Nobody was bitten by a rattlesnake, though late this afternoon one did sink its fangs into the fabric of Bill Ransberger’s pants.