This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Janis came home to Port Arthur one last time in August 1970, seeking satisfaction: revenge, acknowledgment of her superiority, perhaps an apology or two from those who once called her a pig and a whore and threw pennies at her, perhaps simply acceptance at last, at last. It was her tenth high school reunion, and in those ten years the world had gone crazy. In that span of time, Janis had become a star, an icon of the counterculture, a wealthy woman, an alcoholic, and a heroin addict. Her whole world revolved at high speed. For that matter, even the world of Port Arthur had begun to spin. Some of the kids wore long hair. The schools had integrated. And when cars trolled along Procter Avenue with the windows down, you no longer heard the Coasters, Chuck Berry, and the sweet nothings of girl groups bubbling out of the radio speakers. Now you heard Janis Joplin.

But the essence of Port Arthur hadn’t changed anymore than Janis herself had changed. It was still a small town where appearances counted, and she was still a thin-skinned rebel—“needing acceptance,” as one of her close friends put it, “while at the same time rejecting the society from which she needed the acceptance.” Janis was still of Texas, in her music and in her soul. No matter how frayed the bond, no matter how much she slashed away at it, no matter how much it tortured her, there it was. Unlike Janis, her tight circle of high school friends hadn’t bothered to attend this gathering. Reunions weren’t their trip; they didn’t give a damn if Port Arthur accepted them or not. And not one of them had achieved the fame and fortune Janis Joplin had. Yet all of them had found a way to make peace with their pasts.

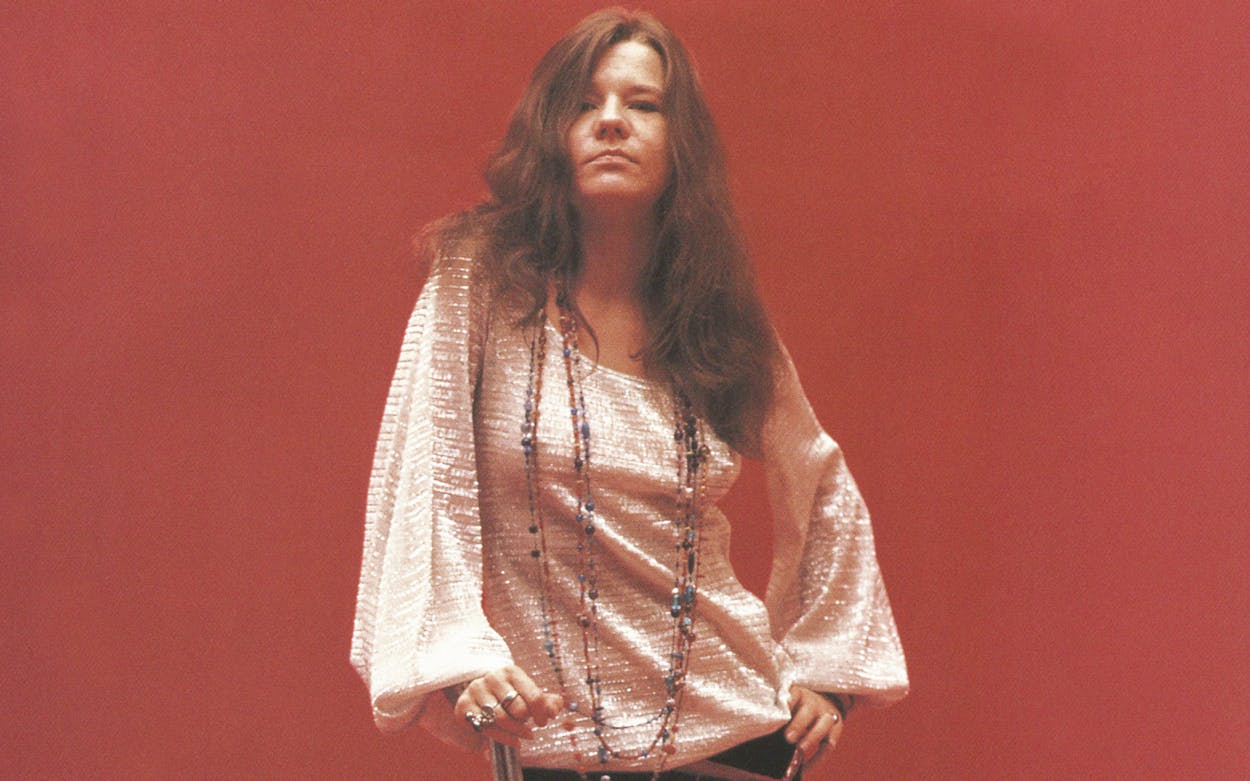

Janis had not, nor would she. She arrived at the Goodhue Hotel in full flourish, wearing purple and pink feathers and open-toed silver slippers and oversized sunglasses and fluorescent orange paint on her toenails and enough metal on her wrists and forearms to build a prison cell, accompanied by three long-haired guys of undetermined origin. Her peers spent the evening gawking at her or making catty comments out of her earshot. Several asked for autographs. At least one of them, who had never been close to the singer, assured Janis that she’d given the media the wrong impression about Port Arthur’s treatment of her. “Janis, we liked you!” she insisted.

Janis did not respond. She had pledged to a reporter that she would attend the Thomas Jefferson High School reunion “just to jam it up their asses,” to “see all those kids who are still working in gas stations and driving dry cleaning trucks while I’m making $50,000 a night.” But now that she saw them and they saw her, what was there to say? What deep scars could suddenly disappear? What damage could possibly be undone? She spent the evening drinking, then returned to California, where she phoned a close friend, her publicist and eventual biographer, Myra Friedman. In a dejected voice she told Friedman, “Well, I guess you can’t go home again, right?”

Less than seven weeks later, on October 4, 1970, 27-year-old Janis Joplin died of a heroin overdose. Her will stipulated that her body not be buried in Port Arthur—rather, that it be cremated and the ashes spread across the Pacific coastline of Marin County, California. With Janis’ last wish fulfilled, Port Arthur was forever denied a piece of its prodigal daughter’s heart.

The movement to reunite Janis Joplin with her native state has been made possible only by redefining Janis Joplin. As the years passed, visitors from all over the world would drive through Port Arthur, searching for tributes to the city’s most famous celebrity. Yet no sign, no building bore her name. Her childhood home had been torn down in 1980. Her family had moved to Arizona. And those who remembered Janis did not always have nice things to say. For what had she said about Port Arthur? A town filled with bowling alleys, rednecks, and plumbers, leading “such tacky lives.” Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, and John Lennon may have appalled the establishment, but at least they didn’t get personal about it. To some in Port Arthur, Janis Joplin symbolized the very worst of her generation. She was a spiteful, ungrateful ragamuffin who made a spectacle of herself, slept with everyone in sight, and ultimately drugged herself to death—though not before influencing thousands of gullible children toward the same doom. Small wonder that when another Joplin biographer, Ellis Amburn, strolled through Port Arthur a few years back and asked passersby why there wasn’t a street named after Janis, “most people were outraged that I would even bring up the subject,” he says.

Amburn would later term Port Arthur “a town without pity.” But by the mid-eighties, fate had dealt the town a pitiless hand. Oil production had dried up. In 1984 Gulf laid off 1,600 workers in a single day. One year later, unemployment in Port Arthur stood at 25 percent. The city’s downtown area looked as if it had been beaten and left for dead. All of this is not to say that civic leaders were completely receptive when, in 1987, the owner of a local barge and tugboat business and a former classmate of Janis’ named John Palmer offered to pay for a bust of the singer if the city would agree to unveil it during a fitting memorial ceremony. Recession or no, Port Arthur still wasn’t inclined to honor drug users—especially drug users who publicly ridiculed Port Arthur.

But what was the use in fighting anymore? Janis was dead and Port Arthur had wounds to heal. It happened, then, that on January 19, 1988, a crowd of about five thousand people wedged themselves into the Port Arthur Civic Center and viewed the unveiling of the bust. They cried and sang along to “Me and Bobby McGee,” the Kris Kristofferson song that Janis once sang like the sweetest heartache: “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.” One Port Arthuran after another lined up and told the dozens of reporters in attendance, “We love Janis.” That and, “We forgive her.”

Among those attending the event was Laura Joplin, Janis’ younger sister. Two years earlier, their father, Seth Joplin, had angrily declared to Houston Post reporter Clifford Pugh, “The people in Port Arthur disliked Janis and did everything they could to hurt her.” But Seth was now dead, and Laura found herself deeply moved by Port Arthur’s desire to make peace with the past. Then and there, Laura Joplin determined to write her own biography, which would paint Janis in a different light: Janis as a beloved girl, even a normal girl, in a world that was not so troubled after all.

Thus began the recasting of Janis Joplin—and by extension, of the era that begat her. The bust of Janis now sits in a Port Arthur library, surrounded by odds and ends donated by the Joplin family. The impression these objects leave is that of a thoroughly conventional girl, one who sang in the church choir, painted religious motifs, wrote loving Mother’s Day cards, and had her high school yearbook signed by dozens of pals. These tokens represent only a sliver of the woman. Yet it is the sliver that gives the city comfort. Port Arthur cannot find it within itself to immortalize what was immortal about Janis Joplin.

Those characteristics—the outrageous behavior, the excesses, the voice that wailed a hurt that could not be contrived, the need for love that no one could sate—are now dismissed by Port Arthurans as media hype. “I think she made up every single thing in that book,” a local librarian told me in reference to Myra Friedman’s critically acclaimed biography of Janis, Buried Alive, which has just been updated and rereleased. The author unapologetically discusses “Janis as victim,” primarily of her own pathologies, and paints a desolate portrait of Port Arthur: “The air is gummy with humidity, and it howls—heat, mediocrity, boredom.” Soon, however, the most unpopular book in town will be Ellis Amburn’s Pearl: The Obsessions and Passions of Janis Joplin. Amburn, who himself has bad memories of growing up in Texas, lays the Janis Joplin tragedy squarely at the feet of Port Arthur. “Though she survived into adulthood,” he writes, “the emotional deformities sustained in youth prevented her from having a normal life.”

Port Arthur, and the Joplin family, will hear nothing of this damaged account of Janis. “If you think of Janis as a wounded puppy, you’ve got the wrong image,” says Laura Joplin, whose Love, Janis has just been published. The book is part of her family’s organized effort to control Janis’ life in a way that they could not when she was alive. They have sued a Seattle theater company over the right to base a play on Janis’ life, denied Friedman permission to reprint letters from Janis that were included in the first edition of Buried Alive, and sent letters to Port Arthurans implicitly urging them not to cooperate with Amburn’s book. Surprisingly, the family’s version of Janis’ life is both earnest and comprehensive. Yet its central mission—that of normalizing Janis—is apparent on almost every page. In Love, Janis, pages and pages are devoted to childhood scenes that cast the Joplin family in a dubiously Rockwellian glow. The pain of her high school years is attributed simply to adolescence, her oddball demeanor to the group she hung out with.

The book’s distinguishing feature is that it contains 25 letters from Janis that have never before been published. The letters are to Janis’ mother, and they reveal a young woman desperate to please her parents—desperate, in spite of her brave new world, to be the normal Port Arthur girl she could not possibly become. Unfortunately, Laura Joplin has used these letters to suggest that her sister was, in the end, just another young woman with a dog, a boyfriend, a nice apartment, a well-managed bank account, and a promising career. One of Janis’ roommates in San Francisco and closest friends, Sunshine Nichols, recalls the singer mocking the letters even as she wrote them. “This is what just drives me insane about Laura basing her book on these letters,” says Nichols today. “I mean, anybody who has left home knows the letters you write your parents are lies.”

In fact, the letters are exactly half the truth, the words of a woman torn in two.

Janis Joplin grew up in Port Arthur in the late fifties, moved to Austin in the early sixties, and said good-bye to Texas in 1966. Her path to San Francisco had already been blazed by other young Texans who felt stifled by the culture of their native state. She caught up with them in a hurry: If there exists an icon of the counterculture, it is Janis Joplin. And yet psychically she remained trapped within the fault line that divided the two cultures. Janis was a middle-class white girl who sang the blues. No one had any difficulty reconciling this: The ear didn’t lie, and besides, Janis’ blues were a matter of public knowledge, excruciatingly so. Perhaps in counterculture etiquette, it was bad form to show anything but indifference toward the world you left behind, but Janis Joplin was far too honest to conceal her agony. Practically up until her last breaths, she spoke of her native state with the kind of hostility anyone could recognize as the language of the spurned: “They laughed me out of class, out of town, and out of the state.” She said it so often that today Port Arthurans and the Joplins have had to resort to the shaky claim that Janis’ whole feud with Texas was just a well-rehearsed publicity hook that she and the media played for all it was worth—as if to suggest that the generation gap was nothing more than a PR ruse perpetrated by Timothy Leary and Spiro Agnew.

Yet it would be unfair to expect Port Arthur to make sense of the sixties when no one else has. The era dawned in the middle of a post-war daydream, when towns like Port Arthur were well-off and had no reason to anticipate anything but more of the same. By the time Janis Lyn Joplin entered Thomas Jefferson High School in 1957 at the precocious age of fourteen, Port Arthur had 57,000 residents, the majority of them beneficiaries of the oil boom. The boom meant that workers could afford a decent home, that their roads would be well tended and safe, and that their children’s schools would be well financed.

There remained something disquieting about the oil-town culture, however, something that traveled through the air with the rest of the refinery fumes, something that was not readily exhaled. A kid could get a good education in Port Arthur. But as David Moriaty, one of Janis’ schoolmates and longtime friends, says, “There was no social premium on being educated. In a normal small town, if you get educated, you become a banker or lawyer and attain a position of standing. In Port Arthur, the stillmen made fifty thousand dollars a year without much schooling.” The middle-class life made possible by the port was accompanied by a churchgoing small-town moral code. But the port also brought in other elements. Brothels operated in plain view. Gambling joints openly advertised their activities. “When we were in high school,” says Tary Owens, another friend and classmate of Janis’, “the city was on the one hand very straitlaced. But on the other hand, the town was absolutely wide open. I mean, the hypocrisy just glared.”

“The blacks in town, at least 40 percent of the population, lived ‘on the other side of the tracks,’ ” writes Laura Joplin. If oil-town prosperity reduced some of the financial inequality between the races, oil-town culture kept blacks in their place. During Janis’ last year of junior high, a frequent debate topic was “Will federal aid to education bring integration?” As Owens, who was on a debate team in Beaumont, recalls, “We weren’t allowed to argue the pros and cons of integration—it was a given that integration was a horrible thing. The argument instead focused on whether you could get federal aid without having to integrate.”

Still, by reading Jack Kerouac books, Janis and her friends got a taste of the black world; more importantly, they heard black music on the radio. By the late fifties, Elvis Presley had been drafted and Buddy Holly had died, and little was left that deserved the term “rock and roll.” In contrast to the sickly sweet pop tunes that dominated white radio stations, the music of traditional folk and blues musicians such as Willie Mae Thornton, Odetta, and Leadbelly carried a raw honesty that was devastatingly seductive to Janis’ crowd. Devastating, because that raw honesty served only to underscore the inconsistencies in Port Arthur’s moral fabric.

Had Janis Joplin been able to overlook these inconsistencies, she might have passed her days in Port Arthur untormented. For there was much to recommend the girl. She was intensely bright, an excellent student, with a natural gift for painting, and her doughy features were not without their appeal. But the same acute sensitivity that made her a painter also made her resent the social obstacles to individuality. By her junior year in high school, they seemed to hit Janis all at once: Why did girls have to wear their clothes and hair just so? Why were the practices of drinking, cursing, and having sex forbidden and yet widespread throughout Port Arthur? And why could you listen to black music on the radio and yet not have black classmates in school?

“A key to her personality was that she could not abide hypocrisy,” says David Moriaty. Janis spent her junior year hanging with the senior beatnik crowd, which included Moriaty, a jazz musician named Jim Langdon, and a music enthusiast named Grant Lyons, who Janis would later credit with having introduced her to the music of Leadbelly and Bessie Smith—the music that inspired her to sing. She wore black turtlenecks and tights (the closest she could get to pants, which were forbidden by school authorities) or sometimes skirts, which she took pains to hem just above the knees. They passed the evenings driving restlessly through town, singing along to the songs on the radio—Janis and the boys, freethinkers plowing through nights that burned with the demon glow of the refinery lights.

If the boys were a little weird—and they were—then that could be forgiven. A guy was expected to go off the beam now and again. But when Janis fell into their company and took the night drives and drank beer and dyed her hair orange and hollered “F—k” in the high school hallways, that was something else again. Talk began to spread. She was weird. She was obscene. She was no longer a virgin. She was a whore! Boys who had never met Janis bragged openly that they had slept with her. Girls in the locker room cast furtive glances toward Janis’ private parts to see if there existed some kind of visible evidence of her promiscuity. The barbs were aimed specifically at Janis, the female—despite Laura Joplin’s assertion, in Love, Janis, that “the guys got as much flak as Janis did.” (Tary Owens, who was interviewed for Love, Janis, distinctly recalls, “She bore the brunt of the abuse.”) But for a time it was only low talk. “When she was in our group in high school, she was under our protection,” says Moriaty. “But after we left, she got messed with. Her senior class essentially turned on her.”

For all the differences between the Joplin biographers, they agree that Janis Joplin’s life took a drastic turn for the worse in 1959. Her protectors had graduated. She had grown pudgy, and her acne festered to the point that her face had to be sanded. Classmates began to follow her down the hallways, calling her a pig, asking her for sex, goading her into saying the word “F—k.” Rather than ignore them, she screamed back obscenities. Janis could not keep her mouth shut. She decried segregation in class and thus was declared a “nigger lover.” She continued to wear her skirts short and to spend evenings with beatniks at the Sage Coffeehouse or slugging beer in Louisiana juke joints, ensuring her status as a cheap girl. It is possible that a part of her relished her position as teenage outlaw. It is absolutely certain that she was not about to change for anyone. Yet it is equally certain that Janis suffered—not simply out of frustration over Port Arthur’s unwillingness to concede that her way was the right way, as Laura Joplin theorizes, but also because she felt socially inadequate. Privately she would paint her nails and agonize over her figure. She felt downcast when no one asked her to the senior prom and experienced further dejection when the senior class’s steering committee attempted to bar her from attending the school’s Black and White Ball. Many years later, starry-eyed reporters would ask her what it was like to be Janis Joplin, only to hear the singer bemoan her failure to have a husband and children. Beneath the pleasures of celebrity, Janis Joplin—the Janis who was not asked to the prom, the one whose craving for acceptance was matched only by her refusal to behave acceptably—would not find satisfaction.

By the time Janis graduated in 1960, she had already been in and out of psychological counseling and had brought so much turmoil into the Joplin household that Laura fled to the church, where she prayed for God to bring peace to her family. Janis’ parents, Seth and Dorothy, hardly fit the mold of strict disciplinarians, but it was obvious to them that Janis’ behavior invited scorn. She enrolled at Lamar State College of Technology in Beaumont, where most Jefferson High graduates went if they went to college at all—meaning, as Laura Joplin notes, “the gossip mongers who had talked about Janis in high school had followed her to college.” She spent most of her evenings across the state line. She stopped going to class. Not yet eighteen, Janis was already showing signs of alcoholism. She sought counseling. But at least she had music.

No one seems to be able to recall exactly when Janis discovered she could sing. They remember only that when Janis came to her friends offering proof of her talent, they listened to her voice and agreed: God, yes, she could sing. At parties she took to mimicking whatever was on the phonograph: Joan Baez, Jean Ritchie, Bessie Smith, Odetta, even Little Richard—she could do them all. As her confidence in her voice grew, her interest in painting declined. Among the Joplin biographers, the popular explanation for Janis’ giving up painting is that she met a fellow who could paint better than she could, and realizing that she could not be the very best, she put down her brush for good. That Janis did, in fact, have a competitive streak makes it hard to imagine that she would give up so readily on anything that meant so much to her. What seems more likely is that Janis recognized that singing suited her needs and temperament better. “I don’t think she had the discipline for painting anymore,” says Tary Owens. “And in singing there’s immediate acceptance, and that’s what she was after—love and acceptance.”

In the summer of 1962, Janis Joplin enrolled at the University of Texas at Austin. The change would do her good, and Janis was ripe for change. She had spent the previous year in Venice, California, haunting the coffeehouses, hitching from one bar to the next, having sex with strangers. She brought back a World War II bomber jacket, which she wore inside out, along with a smug awareness of street life that gave her instant cachet with the Austin hipsters who congregated just west of campus at 2812½ Nueces, at a building that came to be known as the Ghetto.

Built in the twenties, the Ghetto consisted of eight apartments, some fairly comfortable in size, some not much larger than a closet. The rooms rented for $35 to $65 a month, utilities included. Some of the occupants were young men who had just come out of the military on the GI Bill; others were musicians, artists, and political leftists. At times it was difficult to tell just who lived at the Ghetto, because a rotating cast of individuals tended to crash out there on the hammocks and chairs and sofas that had been dragged out into the yard to accommodate the evening festivities. There was always a party at the Ghetto, usually with musicians jamming—and usually, by 1962, featuring the powerful voice of Janis Joplin.

Though Austin as a city was light-years ahead of Port Arthur in its cultural eclecticism, the atmosphere at UT reflected the numbness of the country at large. The males wore their hair short and their clothes starched; to grow a beard was to foreclose any possibility of a job interview. The young women stuck to gray wool skirts, white bobby socks, penny loafers, white cotton blouses, and beehive hairdos. Recalls one of Janis’ friends, “You could go on campus in between classes and see just hundreds of women who were dressed exactly like that.”

The Ghetto crowd kept their own table at the Student Union’s Chuck Wagon Cafeteria. Among them, none stood out as alarmingly as Janis, who wore jeans, a dirty blue work shirt, and no bra. SHE DARES TO BE DIFFERENT! declared a story about Janis in the Daily Texan (written by Pat Sharpe, now a senior editor at Texas Monthly), and indeed it was a dare that entailed certain risks. “There were only a handful of us oddballs there,” says Powell St. John, who lived at the Ghetto and who was beaten up by fraternity boys for his beatnik appearance. “You had to kind of cluster together and keep your heads down.”

But provoking frat boys was not all Janis’ new gang had to fear. The repressive culture at the university had darker manifestations than tacit dress codes. There lingered an odor of McCarthyism in the early sixties, an attitude that freethinking should be not merely discouraged but treated as a serious threat. When a former high-ranking UT official retired three years ago, he left behind boxes of papers, including a list with the heading “Ghetto.” A note at the top of the list says, “The following information was extracted from the records of the Office of the Dean of Student Life.” It consists of 68 individuals, along with information such as their majors, their home addresses, and their disciplinary records at the university, and comments such as “one of the leaders of the Ghetto group,” “secretary for the local chapter of the Young Peoples Socialist League,” “believed to be using heavy drugs,” “believed to be a homosexual,” “suspected of sabotaging the air raid sirens in Austin,” “believed to be very promiscuous,” “believed to be a communist,” “has had trouble with bad checks,” “has psychiatric problems,” and “pathological liar.” Among those listed are The Gay Place author Billy Lee Brammer, cartoonist Gilbert Shelton, several current or former professors and government officials, Dave Moriaty, Tary Owens, Powell St. John, and Janis Joplin.

Recalls Travis Rivers, who attended UT before moving to San Francisco in the early sixties, “I used to say, ‘The eyes of Texas are upon you—at all times.’ ”

But none of the Ghetto crowd was fully aware of the surveillance activities—least of all Janis, who smoked marijuana despite a prevailing paranoia that meant, as Owens says, “You didn’t tell your best friend you smoked pot.” Janis felt utterly sure of herself. Among her crowd, which included several other women, she distinguished herself as a singer, and the locals flocked to watch her perform at Threadgill’s, a converted gas station owned by yodeler Kenneth Threadgill where rednecks, beatniks, and English professors alike gathered to hear the bands play for the wage of two bucks and all the beer they could drink. People sat on tables and window ledges to hear the Waller Creek Boys, which consisted of St. John on harmonica, Lanny Wiggins on guitar, and Janis, singing and playing the autoharp. She still mimicked Odetta, Bessie Smith, and Leadbelly, but there was nothing borrowed about her wailing soprano and her bawdy, unrestrained presence.

Janis’ reputation as a singer spread throughout Austin. Back on campus, however, her reputation remained primarily as that of a weirdo, far more so than the reputations of others who congregated at the Ghetto. “The rest of us kept a modicum of going to school or keeping a job,” says Owens. “But she was totally in that lifestyle. Janis once said to me, ‘Tary, I don’t see how you can live in both worlds. I can’t. I’ve got to be all the one way or all the other way.’ ”

She remained, then, the most obvious target for insults. At the close of 1962, Alpha Phi Omega sponsored its traditional Ugliest Man on Campus contest as part of a charity drive. Each fraternity paid $5 to nominate one of its own, who would then dress up in a mask and ragged attire with artificial blood and parade around in hopes that people would spend a dime to vote for him as Ugliest Man. Though no one seems to know how it began, apparently a write-in campaign developed to elect Janis Joplin as the Ugliest Man on Campus. And although she did not win, as is popularly believed (first place went to Lonnie “the Hunch” Farrell), it seems that she did receive votes. Thirty years later, a few people contend that this event was of no consequence to Janis or that she found it amusing or even that she threw her own name into the ring. (“I think that it was easily within the realm of possibility that Janis nominated herself as Ugly Man as a joke,” says Laura Joplin.) But the overwhelming consensus among those friends of Janis’ who attended UT that year is that she was humiliated by the contest. When interviewing Janis’ mother for Buried Alive, Myra Friedman was told by Dorothy Joplin that Janis wrote an “anguished” letter home, detailing the contest’s effect on her.

Less than a month after the Ugliest Man on Campus contest, Janis wrote a song and recorded it at a friend’s house. The song is called “It’s Sad to Be Alone,” and Tary Owens retains a copy of the tape, featuring Janis on autoharp, singing in baleful, desolate tones: “The dusty road calls you, Come again. / The dusty road calls you, Come again. / The dusty road calls you. You walk to the end. / It’s sad, so sad to be alone.”

A week later, Janis Joplin dropped out of school and hitchhiked to San Francisco. Her companions were her autoharp and Chet Helms, a long-haired, deeply spiritual young man who had already hitched to San Francisco the year before to escape the racism and right-wing morality he had encountered in his youth in Fort Worth and at school in Austin. To Janis, Helms seemed to be a worldly and romantic figure. To Helms, Janis was unlike any woman he’d ever met in Texas. Together they hitched to Fort Worth, where Helms’s mother, a fundamentalist Christian, took one look at Janis in her jeans and pink sunglasses and blue work shirt unbuttoned halfway down and informed her son that they could not stay the night. Helms’s brother drove them to the edge of town, past the Stockyards, and deposited them there.

Some fifty hours later, Helms and Janis were in San Francisco’s North Beach. That night she played her first gig, at a folkie hangout called Coffee and Confusion that had heard any number of wispy Kingston Trio–style singers but nothing like this woman from Texas. She brought the house down, prompting the owner to violate a long-standing house policy against passing the hat. Thereafter, Janis and her autoharp played at the Coffee Gallery, at the Catalyst and the Barn in Santa Cruz, and at St. Michael’s Alley in Palo Alto. Word came back to the Ghetto: Janis had made it.

A year and a half later, in May 1965, Janis Joplin returned to Port Arthur, haggard, her weight down to 88 pounds, her arms punctured with needle tracks. In the City of Lights she had met all her inner demons, the holes in her soul she filled with all the sex and drugs her body could withstand. She spent equal time at the Amp Palace, a Grant Avenue cafe where amphetamine junkies hung out, and at the Anxious Asp, a lesbian bar. She was doing speed and heroin, bouncing from one sex partner to the next, fast revealing herself to be what her classmates at Jefferson High had accused her of being all along.

Her singing had won her notoriety, including attention from record companies. Yet her capacity to self-destruct had overwhelmed her ambitions. She injured her leg in a motor-scooter accident, got beaten up outside of the Anxious Asp following a confrontation with a few bikers. Physically and mentally she was going to pieces before her new friends’ eyes. Most of them did drugs too, but what was happening to Janis was nothing to act casual about. Together they raised money to put Janis on a bus and send her back to Port Arthur.

Her lifestyle having edged her toward death, Janis now swung to the other extreme. She resolved to become a good Port Arthur girl. She bought dresses with long sleeves to cover the needle tracks. She fixed her hair in a bun and wore makeup. She enrolled at Lamar Tech. She threw a party at her parents’ house—only this time, the party was for straight Port Arthurans, husbands and wives who did not booze it up.

Janis herself was about to become a wife. She had met a fellow in San Francisco who went by the name of John Pierre Smith, and though little was known about him, Seth Joplin consented when the young man traveled to Port Arthur to ask for Janis’ hand in marriage. Thereafter, Janis picked out her china and her wedding gown. She would become the girl in her letters to her parents, demanding nothing but what the others had, dreaming only the simple dreams of the oil town.

But Janis’ fiance never returned to Port Arthur, and with that humiliation, her newly straightened life began to tilt. She found her classes at Lamar Tech dull and unchallenging. She took several opportunities to visit her friends in Austin. On Thanksgiving weekend in 1965, Janis performed at the Half Way House Club in Beaumont. Among those who saw the young woman with the bun and the freshly pressed dress was her old beatnik friend from Jefferson High Jim Langdon. Langdon was now writing an entertainment column for the Austin American-Statesman. He was not as stunned by her new look as by her startling evolution as a singer. Both in print and in person, Langdon encouraged Janis to play wherever they would let her play.

Janis returned to Austin, now with guitar in hand, performing at Threadgill’s, the Eleventh Door on Red River, and the Methodist Student Center. Her old band mate Powell St. John sat in the audience one night and was awed. If Janis can stay straight, he thought, we’ll have another Odetta.

If she stayed straight. No one was more aware of that provision than Janis. “California is behind me,” she would say. But now she looked ahead, and the road through Texas simply went around and around. There remained few clubs in Texas, and there remained in Texas a hostility toward its freethinking sons and daughters. One by one they were leaving Texas: Steve Miller, Boz Scaggs, Mother Earth, the Sir Douglas Quintet, the Thirteenth Floor Elevators. And not just the musicians. Chet Helms was organizing musical events, Travis Rivers was opening the legendary Print Mint poster shop, and Wichita Falls native Bob Simmons was on his way to becoming one of the nation’s seminal FM disc jockeys. But not in Texas. All of them had gone to San Francisco to blossom, and others still would follow, deserting Janis.

Sometime in 1966, Travis Rivers learned that Chet Helms had been auditioning vocalists for the band Helms was managing, Big Brother and the Holding Company. More than thirty women had tried out, but none was what the band was looking for. The band members had heard about Janis’ talent, but they weren’t sure if she was right either.

The issue didn’t come to a head until Rivers and a friend named Mark borrowed a 1953 Chevy and drove to Austin. There, Rivers learned from friends that Janis had gotten off of drugs, was attending classes at Lamar Tech, and was making straight A’s. It sounded to Rivers as if Janis had finally found happiness. “So I decided not to call her,” he says.

Early one morning, Rivers was asleep at a friend’s house in Austin when Janis showed up, fresh from a gig in Bryan. Rivers felt obliged to tell Janis about the Big Brother audition. Janis mulled it over. As she had to many of her other friends, she told Rivers that she felt stuck in Texas but fearful of San Francisco. She wanted to become famous, but she didn’t want to fall back into her drug-dependent ways. Rivers could see that the dilemma had been eating at Janis for some time.

That night Janis and Rivers went to an Austin club and watched Boz Scaggs’s former band play rock and roll. Janis imagined herself without her autoharp, without her guitar, rocking the house with a full band. Then she turned to Rivers. Her eyes were on fire. “That’s what I want to do,” she said. “Man, let’s go!”

First they drove to Port Arthur. Rivers sat in the car outside the Joplin house while Janis explained her decision to her parents. When she returned to the car, she gave Rivers the impression that her parents had given their approval—which was hardly the case. From there they drove to Beaumont, to Lamar Tech. Janis met with her counselor, who advised her that she should find some balance between her straight life and her creative life. Then she went to the Lamar Tech registrar’s office to report that she would be leaving the state and would like to retain the option to return for the fall semester.

Janis and Rivers drove back to Austin. They made a beeline to the house of Houston White, who would later found Austin’s Vulcan Gas Company nightclub. Rivers used White’s telephone to dial the number of Chet Helms, then passed the receiver to Janis. Without hesitation, she relayed her interest to Helms and also her concerns. Where would she live? How would she support herself? And what about all the drugs?

Helms loved Janis. He wasn’t going to deceive her. Sure, drugs are still around, he told her. But the scene has changed. Things are less reckless, more relaxed. Speed and heroin are out; organic drugs are in. As for money, Janis would make plenty with Big Brother and the Holding Company. But until she did, Helms would put her up himself. And if things didn’t work out, he would personally pay her way back in time for the fall semester.

Okay, said Janis. She was on her way.

Hastily she packed and contacted a few of her friends. Jim Langdon told her she was making a mistake: She should play things slowly, groom her skills in Texas for a while, establish herself as a solo artist or take up one of the many offers she had received to play for a Texas band. Powell St. John was excited for her, although, as he says today, “I was afraid it would kill her right away.” Dave Moriaty and a few other Jefferson High friends were also horrified. “The first time she came back from San Francisco, she was so near to being dead that we figured the second time was gonna take,” Moriaty says.

But everyone could see that Janis wasn’t going on a whim. “She took it real seriously,” Owens remembers. “It was a business proposition all the way.”

And so in June 1966 she and Travis Rivers set out from Austin, driving U.S. 290 west, pushing on to El Paso and out of Texas; replacing one flat tire with another soon to be; getting stranded with another flat in Golden, New Mexico, and making love in an abandoned house and minding the town’s general store while its proprietor drove to Albuquerque to fetch a replacement tire; meeting up with a gold prospector, lingering with the Indians at a reservation south of Taos, encountering a terrain of volcanic stone and nearby a lake as clear as glass, and making love again; Rivers contending with another flat in Flagstaff, Arizona, while Janis sat on the hood of the ’53 Chevy, reading Zelda; and having $30 wired to them from someone in the Midwest, which fueled them at last to San Francisco.

And in two weeks Janis auditioned with Big Brother, learned the songs, and performed to an adoring crowd at the Avalon Ballroom. Then more of the same, only to bigger crowds and greater acclaim—astounding them at Monterey in 1967, flooring them in New York’s Anderson Theatre and Fillmore East in 1968. Big-time management, a salary of $150,000, a debut album that sold more than a million copies as fast as they could be pressed. An explosive U.S. tour, the breakup of Big Brother, Woodstock, still more fame. Faster and faster, the record revolving at speeds never imagined in Port Arthur, Janis swinging round and round, bottle of Southern Comfort in hand, tracks on her arms again, her voice now a desperate growl, the blues plain for all to hear even after all the years and all the cheers, pig, whore, you can’t go home again, you cannot stop . . .

And then an explosion, and utter silence, and the sky cried ashes of Janis. Perhaps not all of them fell into the sea. Perhaps some never fell and somehow caught a rogue eastern wind and floated lazily toward home, where they now hover with the dreams and the fumes, seeking satisfaction.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Music

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Janis Joplin

- Port Arthur

- Austin