If Carl Sandburg had come from Waco, his name would have been Billy Joe Shaver. Back in the late sixties, when Christ was a cowboy, I first met Billy Joe in Nashville. We were both songwriters, and we once stayed up for six nights and it felt like a week. Today, he’s arguably the finest poet and songwriter this state has ever produced.

If you doubt my opinion, you could ask Willie Nelson or wait until you get to hillbilly heaven to ask Townes Van Zandt, who are the other folks in the equation, but they might not give you a straight answer. Willie, for instance, tends to speak only in lyrics. Just last week I was with an attractive young woman, and I said to Willie, “I’m not sure who’s taller, but her ass is six inches higher than mine.” He responded, “My ass is higher than both of your asses.” Be that as it may, you’ll rarely see Willie perform without singing Billy Joe’s classic “I Been to Georgia on a Fast Train,” which contains the line “I’d just like to mention that my grandma’s old-age pension is the reason why I’m standin’ here today.” Like everything else about Billy Joe, that line is the literal truth. He is an achingly honest storyteller in a world that prefers to hear something else.

Thanks to his grandma’s pension, Billy Joe survived grinding poverty as a child in Corsicana. “Course I cana!” was his motto then, but after his grandma conked, he moved to Waco, where he built a résumé that would’ve made Jack London mildly petulant. He worked as a cowboy, a roughneck, a cotton picker, a chicken plucker, and a millworker (he lost three fingers at that job when he was 22 and later wrote these lines: “Three fingers’ whiskey pleasures the drinker/Movin’ does more than the drinkin’ for me/Willy he tells me that doers and thinkers/Say movin’s the closest thing to being free”).

I believe that every culture gets what it deserves. Ours deserves Rush Limbaugh and Dr. Laura and Garth Brooks (whom I like to refer to as the anti-Hank). But when the meaningless mainstream is forgotten, people will still remember those who struggled with success: van Gogh and Mozart, who were buried in paupers’ graves; Hank, who died in the back of a Cadillac; and Anne Frank, who had no grave at all. I think there may be room in that shining motel of immortality for Billy Joe’s timeless works, beautiful beyond words and music, written by a gypsy guitarist with three fingers missing.

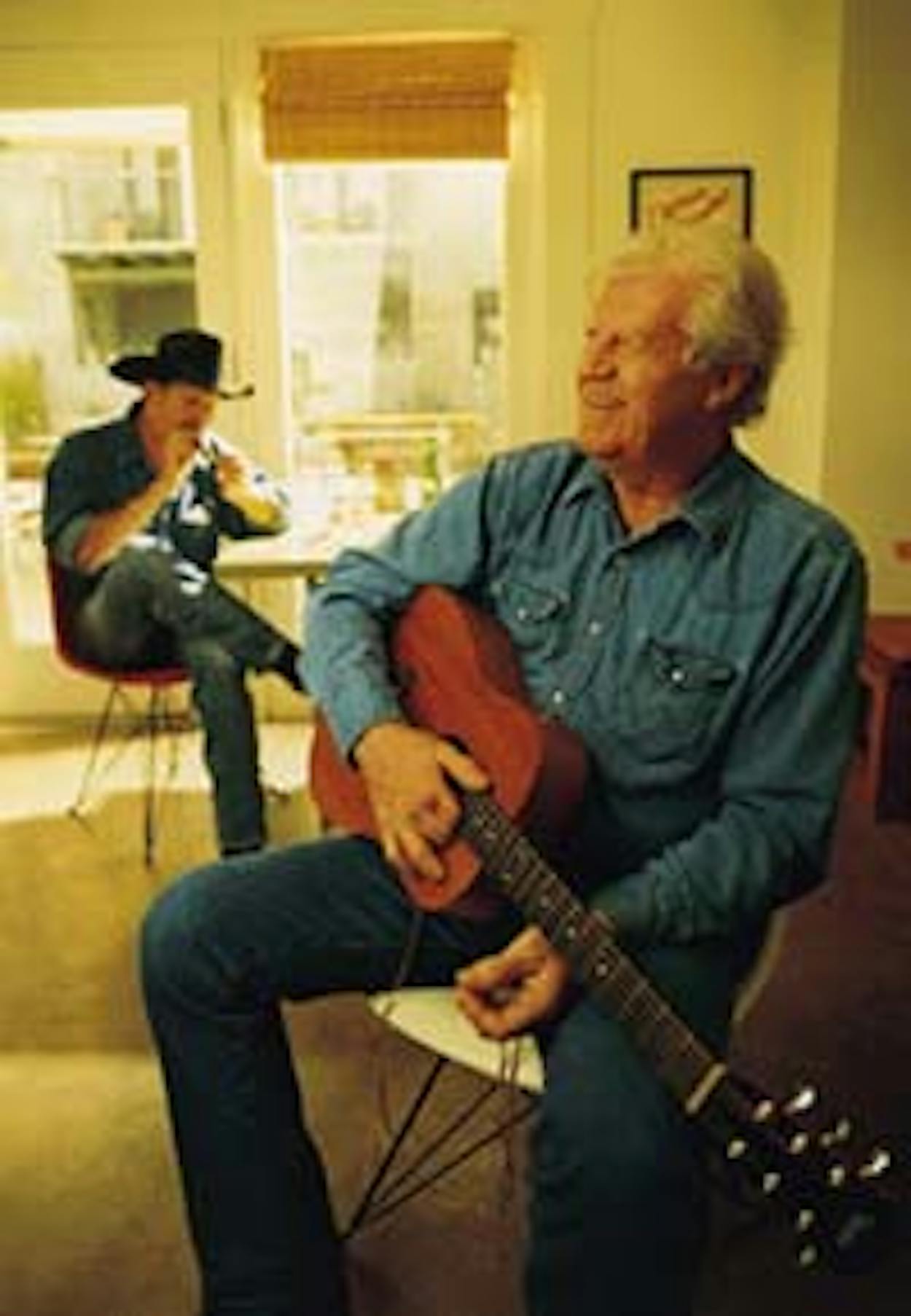

Last February Billy Joe and I teamed up again to play a series of shows with Little Jewford, Jesse “Guitar” Taylor, “Sweet” Mary Hattersley, and my Lebanese friend Jimmie “Ratso” Silman. (Ratso and I have long considered ourselves to be the last true hope for peace in the Middle East.) Pieces were missing, however. God had sent a hat trick of grief to Billy Joe in a year that even Job would have thrown back. His mother, Victory, and his beloved wife, Brenda, stepped on a rainbow, and on New Year’s Eve, 2000, his son, Eddy, a sweet and talented guitarist, joined them. Hank and Townes also had been bugled to Jesus in the cosmic window of the New Year.

I watched Billy Joe playing with pain, the big man engendering, perhaps not so strangely, an almost Judy Garlandlike rapport with the audience. He played “Ol’ Five and Dimers Like Me” (which Dylan recorded), “You Asked Me To” (which Elvis recorded), and “Honky Tonk Heroes” (which Waylon recorded). He also played one of my favorites, which, well, Billy Joe recorded: “Our freckled faces sparkled then like diamonds in the rough/With smiles that smelled of snaggled teeth and good ol’ Garrett snuff./If I could I would be tradin’ all this fat back for the lean/When Jesus was our savior and cotton was our king.”

Seeing Billy Joe perform that night reminded me of a benefit we’d played in Kerrville several years before. Friends had asked me to help them save the old Arcadia Theatre, and I called upon Billy Joe. Toward the end of his set, however, a rather uncomfortable moment occurred when he told the crowd, “There’s one man I’d like to thank at this time.” I, of course, began making my way to the stage. “That man is the reason I’m here tonight,” he said.

I confidently walked in front of the whole crowd, preparing to leap onstage when he mentioned my name. “That man,” said Billy Joe, “is Jesus Christ.”

Much chagrined, I walked back to my seat as the audience aimed their laughter at me like the Taliban militia shooting down a Buddha. It was quite a social embarrassment for the Kinkster. But I’ll get over it.

So will Billy Joe.

“Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me” and “Jesus Was Our Savior,” by Billy Joe Shaver, copyright (c) 1972 Sony/ATV Songs LLC (renewed). All rights administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing, 8 Music Square West, Nashville, TN, 37203. All rights reserved. Used by permission.