ON A SATURDAY AFTERNOON IN HOUSTON, IN TWO BUILDINGS separated by some fifteen miles of roadway—and by ethical distinctions that are harder to measure—more guns are sold than perhaps anywhere else in the United States. Both locations are overrun with buyers, and each will do thousands of dollars of weapons-related business by days end. As the two cater to somewhat different markets, they are not competitors in the strict sense of the word. Yet in the framework of Texas’ concealed-weapons debate, and also the national debate over gun control, they are severely at odds over what responsibilities they should shoulder.

On the west side of the city sits the Katy Freeway location of Carter’s Country, a gargantuan 12,000-square-foot structure that, despite the antlers on the walls and artillery lining the shelves, exudes the apple-cheeked ambience of a Foley’s cookware department. The sales staff is helpful and wholesomely groomed; the stock is graciously displayed; the customers hold their children’s hands and browse at an unhurried pace. Guns, of course, can be bought here, ranging from a $149 .38-caliber police revolver to a heavily modified deer rifle going for upward of $4,000. But a shopper can also stroll into Carter’s Country and walk out with camping gear, hunting licenses, deer feeders, raccoon traps, snake chaps, and taped wildlife calls. It’s a one-stop megashop conceived by Bill Carter, Sr., whose four Houston stores have made him the nation’s leading independent gun dealer, though there are a number of things he won’t sell—imported assault rifles and “cop-killer” bullets, for example. The veteran gun merchant is unusually outspoken about his industry’s ethics, or lack thereof. “The Second Amendment gives us a wonderful freedom,” Carter says. “To protect that freedom, we must be safe and responsible in all ways. But the black market believes that the Second Amendment gives them the freedom to be unsafe and irresponsible.”

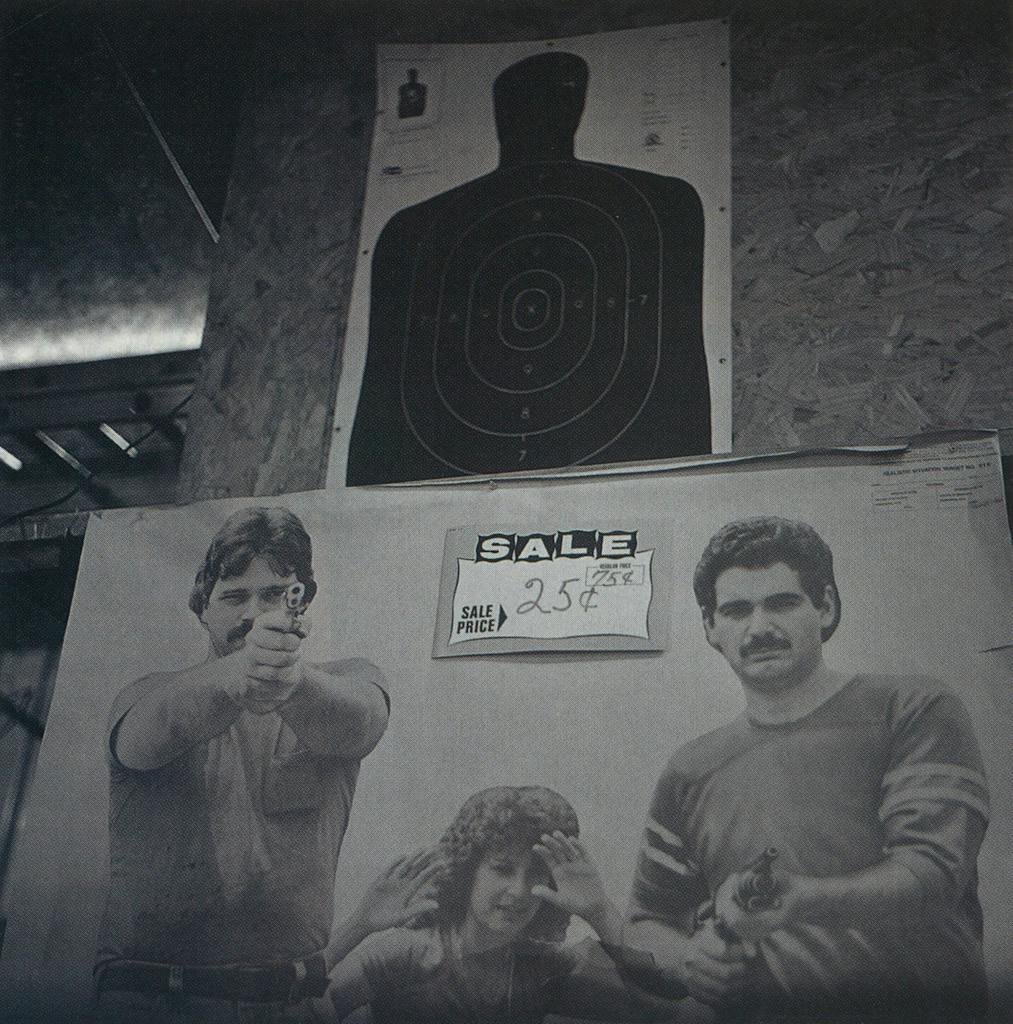

By the “black market,” Carter means the activity that takes place, on this particular day, in the Astroarena, where the Texas Weapon Collectors Association (TWCA) is holding one of the thirty gun shows it promotes each year across the state. Within this cavernous atmosphere, thousands of people weave elbow to elbow among the hundreds of tables set up by federally licensed wholesalers and unlicensed private sellers who pay the TWCA around $50 to peddle their wares. Some sellers don’t even bother with tables—they simply hang signs around their necks advertising what’s available. “No waiting period or paperwork here,” a sign at one table promises. Haggling is common, even expected. There’s no adornment, no goody-goody pretense.

As in the Katy Freeway outlet of Carter’s Country, the shoppers who pay $5 to step inside the Astroarena can buy plenty of things that don’t shoot bullets. But some of the non-firearm merchandise is decidedly hard-core: laser scopes, booby traps, Israeli gas masks, crossbows, Chinese sabers, U.S. marshal badges, Nazi helmets, bumper stickers that read “First Lincoln, Then Kennedy, Now Clinton?” Many of the guns are standard fare, but just as many are elaborately deadly: There are rifles of the Russian-sniper, Chinese-paratrooper, and Egyptian-assault variety, as well as parts for AK-47’s and Uzis. Correspondingly, visitors to the gun show range from earnest-looking yuppie couples to swaggering sportsmen and pale, wild-eyed types who stalk about with an exotic rifle slung over each shoulder and a revolver tucked halfway down the front of their jeans.

If Carter’s Country conjures up the image of a discreet, well-heeled department store, the Astroarena show suggests a freeform bazaar, the flea-marketing of firearms. Both images, however, test one’s comfort level with the right to bear arms. The conflict between Bill Carter and the gun show operators reveals that even within the industry, there’s plenty of unease over rights and wrongs—and plenty of frayed moral edges where the gun-selling pie is sliced.

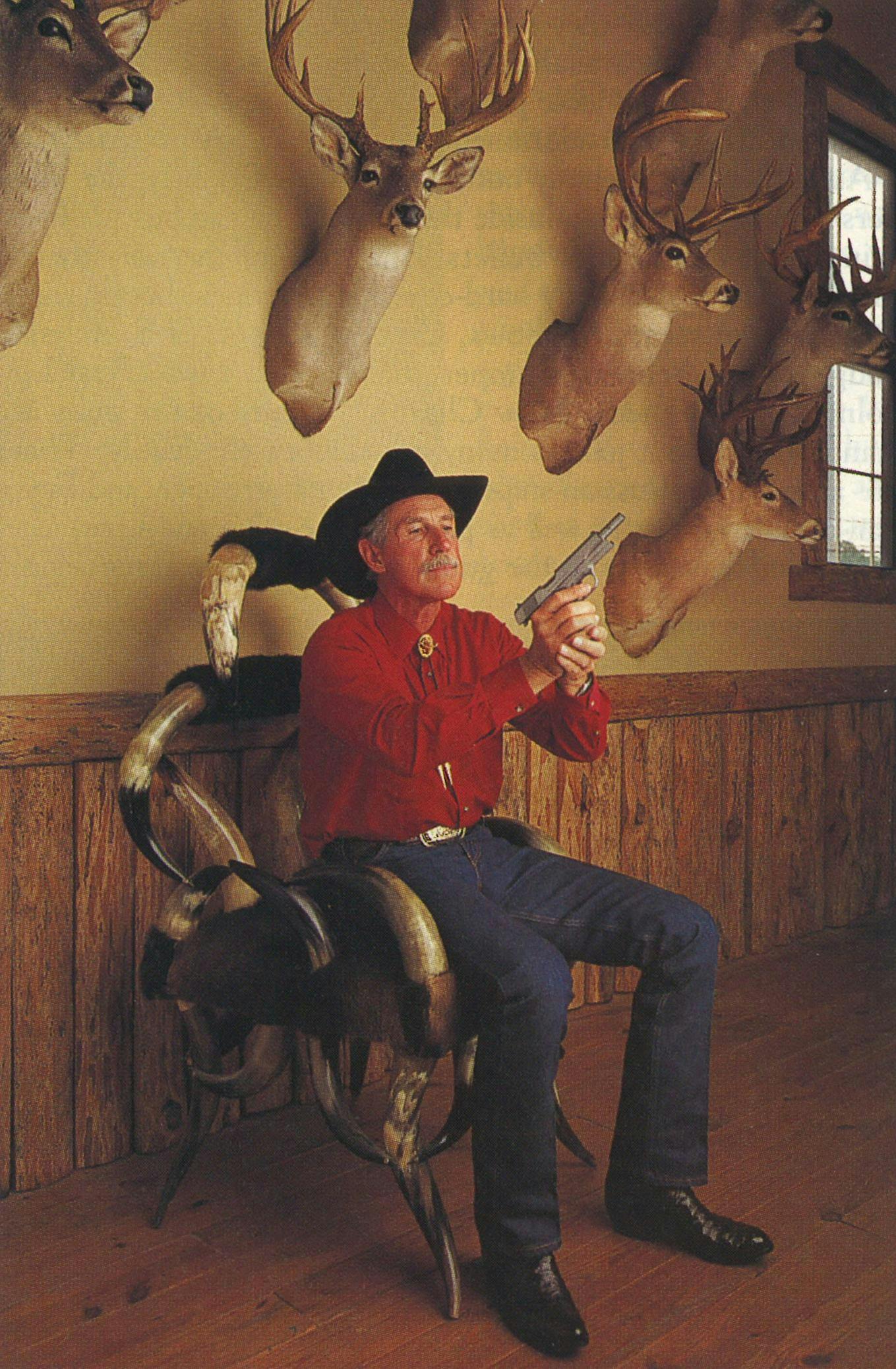

ALTHOUGH THE GAUNT AND MUSTACHIOED BILL CARTER favors cowboy duds—string tie, ostrich boots, a deer-skin vest—he describes himself in the mythic terms of the everyday American dreamer whose faith in God, family, and hard work has elevated him to prosperity. It’s not a hard sell. Raised among the farms and the mills of North Carolina, Carter hung around hunters from early childhood and grew up in the presence of firearms. “My lifetime ambition was to be a gun dealer,” he told me in his Katy Freeway office, which is so crammed with antlers and tusks that upon entering it takes a series of nimble movements to keep from being impaled. “From the day I first got to shoot a rifle, I was smitten.” He bought a .22 rifle at age eleven—with paper route money, naturally.

After stints in the National Guard and the Marine Corps, Carter became a merchant seaman, a job that brought him frequently to Houston, where opportunities seemed plentiful. He and his wife relocated there in 1959, and he took a job as an ironworker on skyscrapers. The pay—$5 an hour—was excellent, enabling him to buy a nice tract home; but what he really enjoyed doing was custom-designing rifles he hand-tooled from wood he got from the Pacific Northwest. He tested the customized firearms at a shooting range on the northeast edge of the city, and only a few months after he moved to town, the owner of the range offered to sell him the place for $15,000 down. Carter scraped together the money. By day he continued his ironwork while his wife worked the range; in the evenings he took over so that she could return to her job as an emergency room nurse at Hermann Hospital.

“We serviced all the rifles that had been sold in the gun stores downtown,” Carter recalls. “We would see a lot of mistakes the retailers were making: mismatched scopes and mounts, the work of good people who just didn’t know the business.” In time, it occurred to him that he could beat the competition with his expertise and a little more display space than his ten-by-ten metal shack afforded. In 1968 a developer bought the range for twice what Carter paid for it, and Carter used the money to buy 33 acres in Spring, just outside the city limits. On that site he built the first Carter’s Country. Six years later came the Katy Freeway store, followed by a Pasadena outlet in 1980 and a fourth store in 1984 on the southwest side of Houston.

Today Bill Carter’s chain is a Goliath among Texas gun dealers, engaging in nearly 400,000 business transactions annually. In addition to the four stores, he owns commercial-hunting ranches in West Texas (near Van Horn), in the Hill Country (near Hunt), and along the border (near Laredo). Carter and his employees also test firearms on those properties—so it’s no surprise that he has significant clout when it comes to shaping weapons manufacturers’ product-development plans. “A lot of the companies up northeast don’t know the terrain they’re marketing to,” he explains, “and a lot of ’em have never seen a rattlesnake.”

It’s interesting, then, to see a gun merchant of Carter’s stature take positions that seem calculated to offend Second Amendment purists. He refused to sell the first Glock handgun, believing it to be too complicated and therefore unsafe for the average consumer. He refused to sell the first imported assault rifle and later encouraged Houston newspapers not to accept assault-weapon ads. The National Rifle Association (NRA) has vocalized its displeasure with Carter, which hardly bothers him. “The NRA isn’t a firearms lobby—it’s a membership lobby,” he says. “I happen to be an NRA lifetime member, but I think they got too radical. They missed the boat on cop-killer bullets. Who really needs those kinds of products? What we have to do in the firearms business is have a conscience. We’ve got to be safe and we’ve got to be responsible.” Beneath Carter’s moralizing lies a practical concern: If the industry doesn’t police itself, the government will. “A lot of gun dealers picked up our philosophy when they saw the Brady bill pass,” he says, referring to the controversial 1993 federal law requiring up to a five-day waiting period so that local law enforcement can review a gun purchaser’s criminal and mental history. “Now, the assault-gun legislation wasn’t completely harmless to us, since it removed the homeowner’s defense weapon of choice—the high-capacity semiautomatic, which we had been selling. But that was mainly a feel-good bill compared to Brady, which has just saddled a lot of good people with a lot of crappy paperwork and really hasn’t accomplished a thing. It has hurt business, and it has lost us part of our freedom.”

That freedom has been curtailed because, Carter says, “the Second Amendment has been abused, unfortunately.” The abusers, he insists, aren’t well-known dealers; rather, they’re gun show merchants who sell whatever they can to whoever wants it. “People talk about buying guns in back alleys,” says Carter, “but that’s not where criminals get their weapons. They don’t have to! They just look at a billboard or a newspaper and see when the next gun show is, and they just go right in. Anything goes. No paperwork. You see obvious criminals buy weapons. It’ll make the hair stand on the back of your neck.”

But what gives Carter’s neck a pain is that many of the gun show merchants don’t have to pay attention to gun regulations, because the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms only has jurisdiction over federally licensed dealers. Private sellers aren’t exempt by law, Carter complains, “but they’re exempt by enforcement.”

Carter says that he knows several gun show merchants who are respectable, but that “the bad guys are too embedded.” Until either the shows’ promoters exert a sense of moral responsibility or the government turns more of a regulatory eye on the shows, Carter fears that crime will increase while the rights of gun owners and gun sellers will diminish. “I’ve been in this business for thirty-five years,” he says, “and until the gun shows cropped up, there wasn’t a major outlet for criminals that I was aware of. And what bothers me most about this is that this irresponsible activity is just going to pave the way for more gun-control legislation. And it’s only going to be enforced on us.”

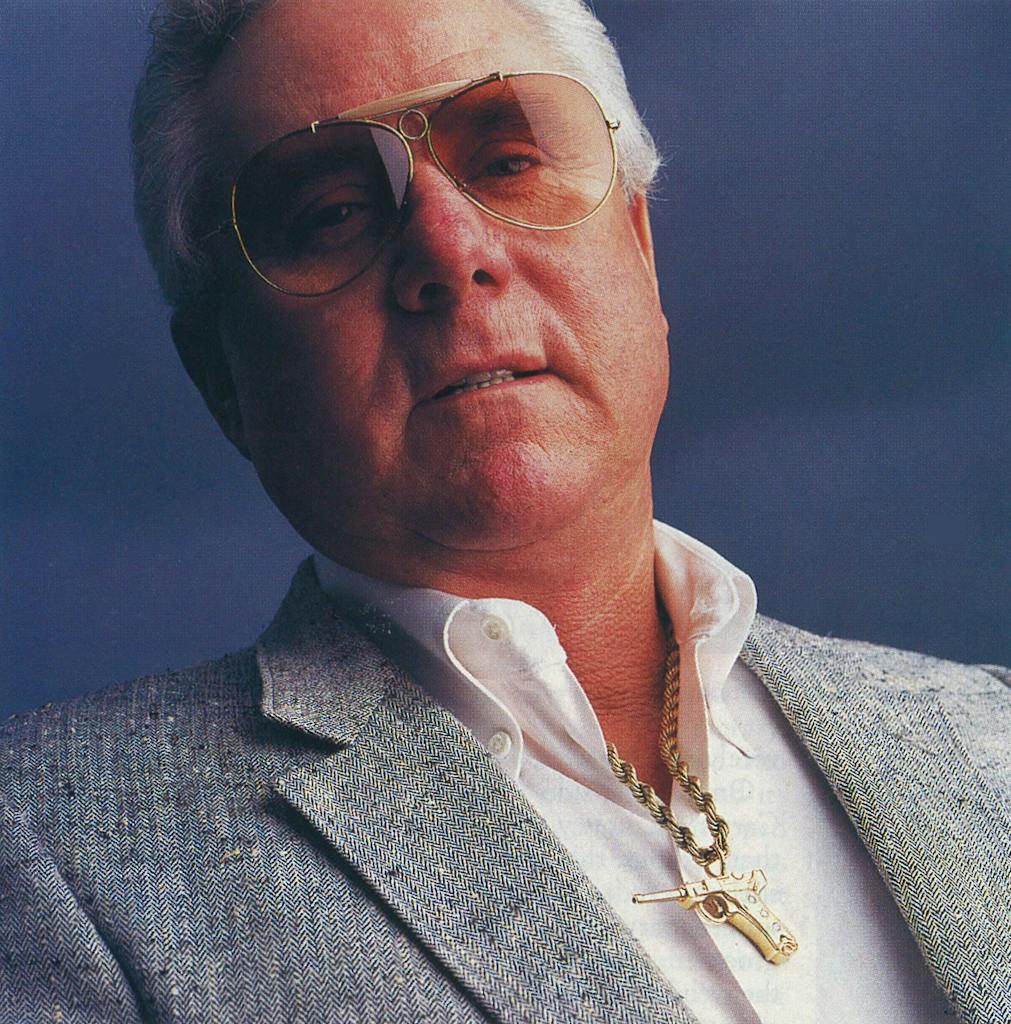

AS IT HAPPENS, ONE OBJECT OF Bill Carter’s scorn has a great deal more in common with him than with, say, Brady bill champion Sarah Brady. Mike Morris, the San Antonio-based director of the Texas Weapon Collectors Association, promoted his first gun show in 1966, the same year Carter hired his first full-time non-family employee at the rifle range. Like Carter’s Country, the TWCA is a family-owned-and-operated business, despite Morris’ status as the biggest of the half-dozen or so gun show promoters in the state. Like Carter, Morris is a lifetime NRA member who supports the concealed-handgun bill—though, like Carter, he’s doubtful that it will bring gun merchants much extra business and worries that it will open the door to further gun-registration efforts. And, like Carter, Morris is a lifelong gun hobbyist who fulfilled his entrepreneurial dream—which is why Carter’s carping strikes him as more than a little bit hypocritical.

“All that talk about responsibility is a cop-out,” Morris declares. “Bill Carter doesn’t give a hoot about his industry’s image as long as his pockets are lined. If he’s so concerned about image, then why isn’t he screaming bloody murder about the guns you see advertised in the classifieds in every major newspaper in Texas? Why does he spend all his time ranting and raving about gun shows? Because we’ve put a big dent in his business. In our shows, there are thousands of merchants competing for the same dollar. In his store, there’s only Bill Carter, selling firearms at higher prices.” To Morris, Carter’s Country is nothing more than a giant business that seeks to crush the gun shows. He scoffs at Carter’s contention that criminals flock to the shows: “What criminal will go through the gauntlet of policemen who stand at our front door and buy a gun from a merchant, who is required to write down every name and address and check identification, when that criminal can just go break into someone’s house and steal a gun?” But no uniformed officer was standing at the door when I entered the Astroarena. And Morris admits he doesn’t have any way of knowing the number of wholesalers at his shows beyond the amount of table space he receives payment for; since he doesn’t collect a commission, he also doesn’t know how many transactions take place. Do the merchants carefully examine a customer’s identification? Do they record every sale? Because Morris usually stands near the front entrance, he can’t be certain. And the gun show merchants don’t have to fill out Brady forms if they say they’re merely, as Morris puts it, “liquidating a private collection.” It’s therefore hard to imagine why a criminal would bother breaking into a home to steal a gun when, with a fake ID or a few persuasive words, he can pick up an arsenal at a gun show.

In his own defense, Morris points out that he is “the only gun show promoter to put a sign on the front door saying that no one under twenty-one is allowed inside unless accompanied by their parent. ” Morris says he does this to discourage gang members, adding, “We’re also the only gun show promoter to have a dress code. If anyone shows up at our door wearing gang clothes, like baggy pants or his cap on backward, I’ll tell him, ‘Sorry, son, we can’t let you in dressed like that.’” So there are limits to the freedom of his entrepreneurial conscience—just as there are limits to Carter’s business ethics. Though Carter won’t advertise domestic assault rifles, for example, he isn’t above selling them. Occasionally, he says, a customer will ask for the Colt AR-15, which was commonly used in Vietnam, and he’ll obligingly fulfill the order without a lecture. “But our customers aren’t really interested in assault rifles,” he quickly adds.

In the end, Bill Carter and Mike Morris aren’t philosophically that far apart. Both would prefer that gun control mean self-control. But their differing versions of how much self-control should be exercised is, finally, the best explanation for why the control is out of their hands.