This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Of my father’s four sisters, Ina Cowan is the quilting one. She has always lived in cotton country—for the last 55 years near little Munday, population 1738, where most of the year you can spot grayish shreds of cotton sticking in weeds by the roadside. Aunt Ina started quilting in 1931, mostly to fill time in the solitude of her husband’s farm. Since then, by a conservative estimate, she’s made a hundred quilts and pieced the tops for two hundred more. Because of her passion, family legend holds that it’s lucky to sleep under a quilt. And one of our favorite stories concerns the time she needed a particular shade of green for a Nine Patch. She happened to notice that her pants were just the right color—so good-bye, pants. Next thing they knew, they were in a quilt.

As her nieces and nephews and other kin grew older or married or moved to cold climates, Aunt Ina gave us each a quilt, always signed and dated in embroidery on the back. She won’t sell her work; you have to be related to her to get one. Aunt Ina is 76 now. She doesn’t hear too well, but otherwise she’s as lively as ever. She still pieces a top every two weeks or so, but it’s harder for her to quilt it out. Two of her favorite quilters, one in Lueders and one in Comanche, are also in their seventies, and they can no longer work because of frailness or ill health. The era of the quilter is passing, and Aunt Ina’s quilts are already heirlooms.

Today the quilt is big business, the latest antique craze. As the electric-blanket generation discovered the charm of the patchwork quilt, it raised the humble coverlet to the status of art—sometimes with a four-figure price tag. Even new quilts are hot items; quilt stores, which sell supplies and lessons and, for the unhandy, the finished product, are booming. Houston alone has four, and its myriad antique stores also handle quilts. Quilt madness has even hit fashion. When designer Ralph Lauren began slicing up old quilts to make trendy skirts and vests, he touched off an angry debate between defenders of the designer and guardians of the craft—both, of course, equally commercial-minded. The truth is that the sudden popularity of quilts has nothing to do with their origins; they’re homemade covers born out of poverty and isolation. All the citified hoopla slights the surviving veterans of the craft: elderly, bespectacled women, small-town holdouts, who still make quilts the way they did when they were girls in the country.

The seventy- and eighty-year-old ladies of Texas quilt because they grew up poor. From the 1830s, when immigrants first started arriving in Texas, until almost a century later, quilts were the only cover available. There were few textile mills and commercial looms to weave blankets, and the cost of moving cloth so far overland from the East made it phenomenally expensive. The only alternative was to recycle old clothes and feed sacks to produce a makeshift blanket. The fact that quilts were often beautiful objects as well was a bonus, a natural outgrowth of the maker’s desire to own something pretty in an otherwise bleak world; she had few other outlets to satisfy her creative hankerings. Today women have no need to create their own art—they can go out and buy it and replace it at will. But their pioneer foremothers had no such choice. Their only option was in their scraps and fingers and minds.

Because quilts were a necessity in the poorly heated houses of the day, most girls started quilting as soon as they could hold a needle. Often boys of the family helped too, for quilt-making was as essential as bread-baking or water-drawing. If a family was very big it needed dozens of quilts; during a norther three quilts to a bed was barely enough, and though with more a sleeper might not be able to move under the covers, at least he stayed warm. Quilts were tucked in as lap robes in wagons, fetched along on picnics, carried to the fields for the baby to play on while the family worked. Because the quilt was so well used and weathered so many washings, it’s rare to find one that isn’t worn. Mint-condition quilts are likely to be the company covers a prudent mother laid away for the circuit rider’s visit.

Many older women in Texas remember quilting as one of their few pleasures in the sparsely populated countryside. “It was isolated out on our farm,” Aunt Ina recalls. “All the neighbors moved out and left us; the older ones died, the younger ones left for better parts. I learned to quilt then, when it was so isolated.” Quilting also provided a chance to sit down and rest after the tedious chores of the day and yet still keep busy—an ethic essential to the hardworking farm families of the plains. Often, though, a woman’s careful labor was unappreciated by anyone but her own family, for quilts were considered common and were never displayed. “If you left a quilt on top of the bed,” Aunt Ina says, “that meant your bed wasn’t made. You had a counterpane or a bedspread to throw over it. But that goes to show you that although a woman had to make quilts, she didn’t have to make them pretty. She did that for herself.”

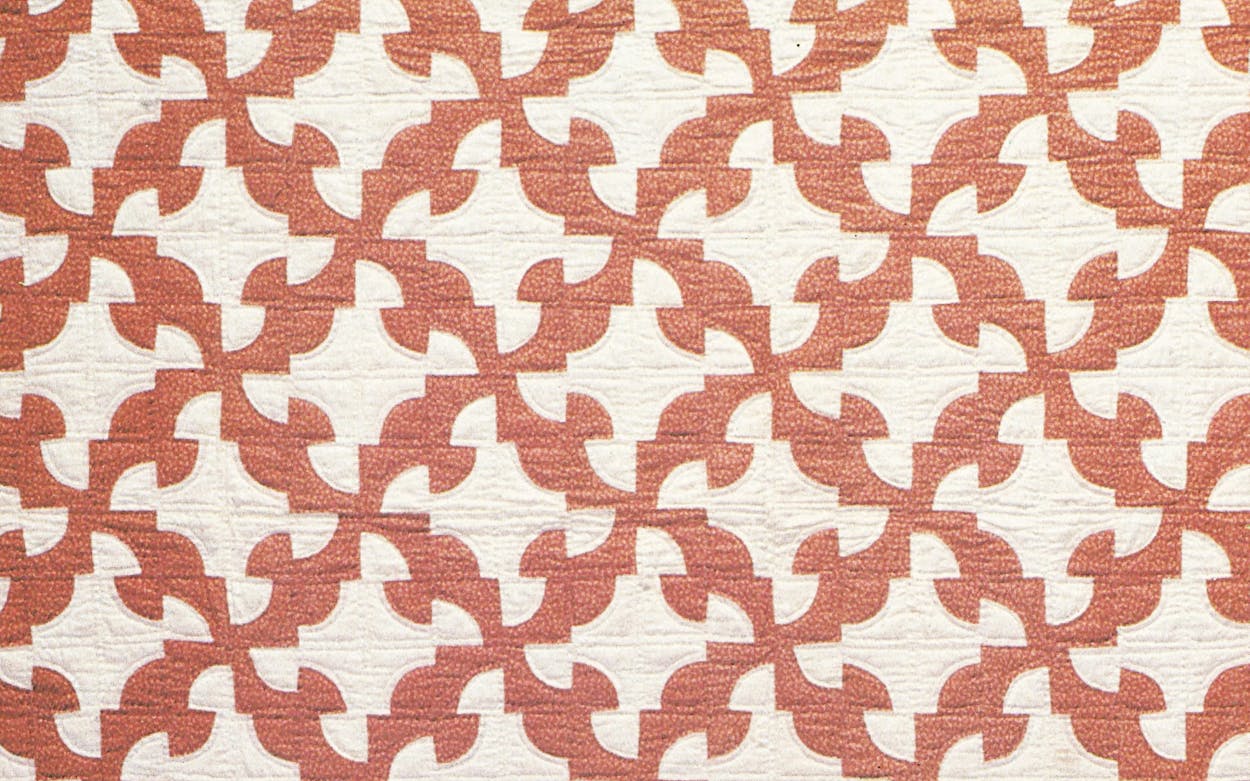

Texas women did a lot to satisfy their own minds. They created some fifty state patterns, more than any other state can claim. Most refer to some historical event or symbol of the state: Star of the Alamo, Texas Ranger, Yellow Rose. But by far the favorite is the Lone Star. At least a dozen different versions exist, the most popular of which is the overall pattern of a giant eight-pointed star. The Texas quilter could take her pick from scores of traditional patterns handed along by her sisters up East—Double Wedding Ring, Grandmother’s Fan, Flower Garden—but she favored patterns that reflected her world: Tumbleweed, Broken Dishes, Log Cabin, Windmill, Spiderweb. Or she was likely to rename another pattern to suit her fancy. A design once known as Job’s Tears or Slave Chain became Texas Tears after the fall of the Alamo. Thirty years later Kansas women were calling the same pattern Rocky Road to Kansas, and soon some of their Texas counterparts rechristened it Crooked Road to Texas.

The bond of Texanness, the sheer hard work, and the simultaneous fun of quilt-making are three reasons the quilting bee existed. Besides getting the work done faster, it provided a ready excuse for socializing, a pleasure that came all too seldom even thirty years ago, when Texas was still largely rural. Quilting bees were especially common when a wedding approached; a traditional dowry was thirteen quilts, though few Texas girls could afford so many. For such an event even the picky seamstress who would never allow anyone else to touch her quilt joined in with a willing hand.

During the Depression, quilting enjoyed a nationwide revival because of the combination of frugality and creativity it offered. In Texas the craft had in fact never declined, but most old Texas quilts date from the thirties, when pastel dyes first became widely available—a boon to seamstresses accustomed to the same old red, blue, dark purple, and brown. Feed and grain companies capitalized on the quilting trend by putting out their products in printed cloth sacks, which became a strong selling point. The aptly named Pioneer Flour Mills of San Antonio still markets its flour in cotton sacks today. The quilting fad of the thirties also revived the popularity of the quilting bee, which in Texas had never really died out; it was simply neighborliness. Although the modern resurrection of quilting exists partly because of the gloss of sisterhood, the old spirit of the bee lives on. It’s a safe bet that every town in Texas hosts a quilting group today, a chance for the local ladies to catch up on the news and work at the same time. In tiny Andice, a handful of ladies—a good portion of the total population—gets together weekly to quilt.

“We’ve been meeting a couple of years now,” says Helen Wade, the baby of the group at 57. “I sure do look forward to it. Right now we’re working on a Lone Star. We’re going to raffle it off for our fire department. It sure is pretty, isn’t it? I think it’s about the prettiest one we’ve made so far, don’t you think, ladies? We don’t have any trouble selling quilts. Why, we had one sold before we ever started on it.”

“I used to supply the refreshments every week,” chimes in Olga Jacob, 70, “lemonade or coffee or such. But now we just drink water, ’cause I learned to quilt.”

“I’ll tell you why we quilt,” adds Lenora Pearson, 76. “It’s an excuse to sit down. ’Course, then you get so stiff you can’t move.”

The steps the Andice group and other quilters follow sound simple but represent hundreds of hours of work. A quilt is a layer-cake cover consisting of a pieced top, a middle stuffing for fullness, and a backing. Once a quilter settles on a pattern, she has to make templates for the basic elements of the design—triangles or diamonds or squares. Tracing repeatedly around these shapes, she proceeds to the endless cutting of pieces. Using as a guideline her mental map of the quilt, she takes careful stock of her fabric colors before she begins piecing each block, or square, in the quilt; to run out of a certain color ruins the overall look. A quilt with mismatched blocks, though, is not necessarily the sign of an indifferent quilter but simply an indication that she had only a limited amount of fabric at her disposal.

The tedious work of trying to eke out the colors makes foresight a big part of her work; a quilt loses something if its maker can drive to a store and pick material to match her decor—and with yardage to spare. Seasoned quilters recycle old clothes and curtains and sheets and anything else because they can’t bear to throw it away. “Half the fun of an old quilt,” Aunt Ina says, “is looking at it and seeing a dress you wore to school, or whatever. Conserving and using up—that’s the pioneer spirit, more than going out and buying pretty new material and making a replica of an old quilt.”

After a seamstress pieces the first block, she still has anywhere from thirty to a hundred or more to go, depending on the size of the quilt and of the block. In medallion quilts, such as the Lone Star, the center star is pieced as a single huge block, while in a Postage Stamp quilt as many as five thousand tiny squares must be sewn together.

Once the quilter has finished the top, she’s ready to set up her frame and stitch the layers together. Most frames today are freestanding, though occasionally a quilter still has one suspended from the ceiling with ropes, to be pulled up out of the way when not in use—a holdover from early days when space was at a premium. Four legs hold wooden boards fastened at the corners; the sides of the frame are movable to allow a worker to roll up the quilt as she goes, so she can easily reach the center. Strips of material stapled to the sides of the frame let her pin in the backing, traditionally a solid piece of “domestic,” or unbleached muslin.

Next comes the batting, or filling. Nowadays polyester batting conveniently comes in rolls, but fifty years ago preparing the batting was one more time-consuming task. Many Texas women had to card their own cotton, often picking up stray bolls from trucks at the local gin yard. They combed it, removed the burrs, washed it, recombed it, and carded it into squares; the rule of thumb was that a stack of cotton squares reaching from a chair seat all the way up the back was enough for a full-sized quilt. Such a filling required a lot of little stitches to keep it from bunching up and spoiling the appearance and warmness of the quilt. The beauty of the stitches—often perfectly straight, tiny things, twelve or fourteen to an inch—was almost secondary. Today quilts have much less stitching, and what there is serves more to outline the design than to secure the innards.

Once a quilter spreads the batting on the backing, she lays the pieced top over it and pins that to the edge of the frame too, stretching it until no wrinkles remain. The tightness makes it easier to sew through the thickness of three layers, which she does using a stubby needle designed to save the back-and-forth motion that would tire her arm. This is the actual quilting. It takes a cautious eye as well as a careful hand; not only is the quilter sewing the layers together but she is also emphasizing or playing down certain parts of her pattern. If there is a plain background or white squares alternated with pieced ones, she covers them with decorative stitching. The final step is binding the edges of the quilt or adding a pretty border.

If you want a quilt, senior citizen centers or small-town quilting groups are your best bet. You can get a new, sturdy quilt made by veteran quilters at a fair price—and in colors and patterns you want, to boot. You’ll also have the satisfaction of knowing the profit is going directly to the makers rather than to a dealer. If you’d rather have an old quilt, try poking around flea markets and keep an eye out for roadside signs; often you’ll find a decent thirties quilt for as little as $50. A more realistic price is $200, though, and if you buy from a dealer, expect to pay a lot more.

But whether you want a new quilt made by old ladies or an old quilt made by young girls, remember what you’re buying: history. “A quilt is something that will outlast anybody,” Aunt Ina says. “A cared-for quilt will last fifty years and be useful, which is more than you can say for some people. I think about that when I’m working on one: This quilt will be here a long time after I’m gone.’ I like old quilts. I used to look at ’em and think, ‘That’s worn.’ But now they speak to me. If they could talk, they could tell you things.

Step by Step

To make a quilt you need determination and a few hundred hours.

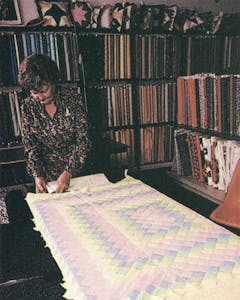

With scissors and thread at the ready, Austin quilting whiz Thelma Hobbs, 63, pieces a Virginia Star. The reverse side shows the network of seams that connect 28 pieces into a single block.

Here Mrs. Hobbs pins a completed top, Trip Around the World, into her quilting frame—quite a job for one person. She has rolled one side of the quilt in so she can reach the center comfortably.

The final work is the actual quilting; Mrs. Hobbs patiently stitches around each individual square. This baby quilt will use up considerably less than the average five hundred yards of thread.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- TM Classics