This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Very early in the trial of Cullen Davis, the richest man ever to be brought to judgment on a murder charge in this country, a shapeless and badly used Panhandle housewife with her cheeks heavily rouged and her hair tinted raven black caught a glimpse of Cullen’s estranged wife, Priscilla, and announced to those around her: “I can tell she’s guilty just by looking!” I mumbled that Priscilla’s guilt or innocence wasn’t an issue in the case, but I knew as I said it that I was wrong. Three months later Cullen walked free, and the housewife wept in gratitude as she thanked her friends and neighbors on the jury.

The housewife had driven more than fifty miles that morning back in August, not realizing that the 52 seats in Judge George E. Dowlen’s Amarillo courtroom would be coveted like tickets to Gloryland. The housewife could have returned home in time to watch Days of Our Lives, but she didn’t. Instead, she waited in the corridor with about a dozen other disappointed middle-aged women, watching the proceedings through a small glass panel about the size of a small TV screen. It was their common experience that women like Priscilla were responsible for the majority of the evils of the world. Their first clue was Priscilla’s expensive outfit with its frills of virginal white lace. Who did she think she was fooling? Then there were the high heels, the cascade of platinum hair, and her shockingly piquant figure. But the clincher, the moral equivalent of the smoking pistol, was the tiny gold cross that the state’s key witness wore defiantly between her silicone breasts.

“Have you ever seen anything so tacky?” the housewife asked the assembly of indignant spectators. What they didn’t know was that Priscilla had carried that same cross in her purse on the night of the murders of her daughter and her lover, the night she had been shot between those breasts and, miraculously, had survived.

“You should’ve seen her yesterday,” another middle-aged woman said. “She wore suede. In August, no less!”

Still another woman remarked that, while she hadn’t actually seen it, she had heard that Priscilla arrived in Amarillo carrying a white Bible and a single perfect lily.

“Why would he ever marry her?”

That was a good question, but one they would not hear answered. Maybe Cullen did it out of a sense of Christian charity, or perhaps because of some well-intentioned flaw in his own personality, some Pygmalion instinct. Hadn’t he tried to help her? Whatever the answer to this riddle, it was generally agreed that the time had come to place blame where it belonged; Cullen Davis’ strange collection of groupies—“the menopause brigade,” one bailiff named them—had resolved to do what they could. They scolded Deputy Sheriff Al Cross for not seeing to it that Cullen’s bed linens were changed regularly. They brought the defendant cookies and pies and flocked around him at each recess. They brought their children and grandchildren to meet him and—for some strange and convoluted reason—had him autograph their copies of Blood and Money. One had him autograph her neck brace, and another offered to iron his shorts and socks. On one occasion the mother of a juror chatted with Cullen.

Not all the groupies were shapeless, middle-aged housewives. There was a nifty, dark-haired young morsel who enjoyed getting Cullen in the corner and discussing sociology. And there was a stream of young beauties, most of them from Fort Worth or Dallas, who frequented the trial. They always sat directly behind the defendant in the courtroom and shared daily catered luncheons with Cullen and his attractive girl friend, Karen Master. One of the most striking was Rhonda Sellers, whose mother is a close friend of Karen Master. Rhonda is a Dallas Cowboys cheerleader and the former Miss Metroplex. The jurors didn’t know any of the beauties by name, but they wouldn’t forget what they looked like.

During each recess you could find Cullen moving freely among his admirers, shaking hands, posing for pictures, exchanging pleasantries. The housewives loved the way Cullen referred to his cell mate as “my old lady,” a carryover from his days as a Texas A&M cadet. At times the security was so informal that, had he been so inclined, Cullen Davis could have walked out of the courthouse and been out of town before anyone noticed. The bailiffs assigned to guard the defendant were openly on his side and treated him as they would a visiting dignitary. One bailiff in fact had once worked for one of Cullen’s companies. There was the day that Cullen walked out of the courtroom and took an elevator to the ground floor, accompanied only by one of his attorneys. Another time when he was left alone in the jail booking office, the telephone rang and Cullen answered it.

Cullen had his own telephone installed in Judge Dowlen’s waiting room and frequently conducted high-level corporate affairs during recesses. Besides being permitted to have catered meals, the defendant was allowed to keep a color TV set in his cell. Although the Potter County jail was so overcrowded that other prisoners slept on the floor, Cullen was at times assigned to a private double-bunk cell. He was always freshly groomed and immaculate in his expensive, conservatively cut business suits, very much the corporate president, collected and in control. Each afternoon when the court recessed for the day, Cullen gathered a fresh change of clothes and in the company of Deputy Al Cross drove across town to see his chiropractor. Members of the press began referring to the Potter County jail as the “Cullen Hilton.” And always there were the groupies waving him on with brave smiles and wet eyes that showed clearly they shared his ordeal. Their eyes were windows into the heart of the community. Their eyes said: We’re for Cullen.

What made all this display particularly weird was the nature of the crime. Cullen Davis wasn’t even on trial for shooting his estranged wife and killing her live-in lover, Stan Farr. He was specifically charged with the cold-blooded execution of his twelve-year-old stepdaughter, Andrea Wilborn, his assumed motive being the elimination of all witnesses. Many times I marveled at the doting housewives who were so quick to embrace the cause of a man three eyewitnesses placed at the scene of the murders. They didn’t merely acquit him in their hearts—they adored him. It was as if he were someone to whom they were beholden, someone whose position, courage, and fortitude set him well above the struggling masses and, in some inexplicable way, promised meaning to all their lives.

I suspect that all the same forces at work on the housewives likewise hit home with the jury. “The Cinderella’s Sisters Syndrome,” you might call it. Why did the Prince pick her? And just where did Priscilla Lee Wilborn Davis get off acting so high and mighty? Since Cullen Davis was one of the richest men in Texas, the selection of a jury of his peers was out of the question. What the court settled for was a jury of Priscilla’s peers, most of whom saw the wealth she had been given as a trust she had betrayed.

In retrospect, Amarillo seems the perfect setting for the murder trial. Amarillo is large enough and flexible enough to contain a cast of characters of Dickensian duplicity and roguish charm. Yet it is isolated, self-contained, and properly aloof. “People here aren’t all that interested in what’s going on in Fort Worth or Dallas or Houston or San Antonio,” Judge Dowlen said. “Most people who had heard about the case at all thought it involved some rich woman from Dallas who shot someone.” Amarillo was considered a “prosecution town,” a place with a strong law-and-order conscience. As one prospective juror explained, “You just know they’ve done something wrong. Otherwise the police wouldn’t have arrested them.” In the case of Cullen Davis this evaluation of Amarillo proved dead wrong. Tarrant County District Attorney Tim Curry admitted later that the move to Judge Dowlen’s court was a “disastrous error in judgment on my part.”

Though Amarillo is the quintessence of the Texas myth, with its foundation in cattle, oil, and natural gas, it doesn’t feel or think like Texas. It feels like the capital of another state, the Panhandle, a place geographically if not culturally closer to Oklahoma City, Topeka, and Denver than to Austin. It is a randy, bullheaded, good-humored cowtown—the kind of town Fort Worth used to be, back before the time of Cullen Davis.

But Cullen’s daddy—and the founder of his fortune—Kenneth (Stinky) Davis, would have felt at home with the profiteers, speculators, adventurers, and roughnecks who settled the Panhandle. A hundred years ago the Great Plains was populated solely by Comanches and great herds of buffalo. Then a man from Illinois named Charles Goodnight established a cattle empire and the rush was on. The land today remains much as it was then, checkered with ranches of enormous size and controlled like feudal kingdoms by the heirs of the old cattle and oil barons. Buck Ramsey, the crippled cowboy, poet, and philosopher, described Amarillo, where he still resides, as “a place where they send their daughters East to be educated and keep their sons at home to learn how to be bastards like their forefathers.” In Amarillo the term “bastard” connotes a certain measure of respect.

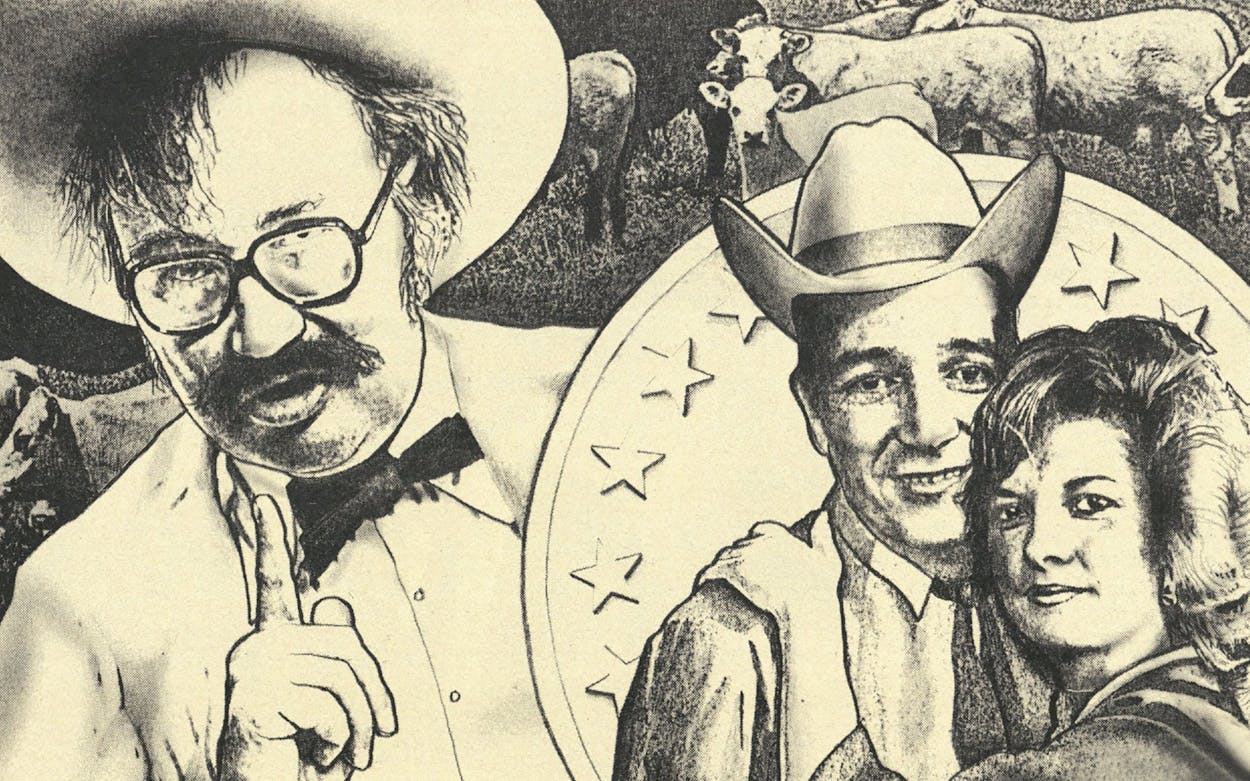

Stanley Marsh 3 and his wife, Wendy Bush O’Brien Marsh, are hardly typical examples of pioneer stock, but examples nevertheless. Wendy’s father, William Bush, was one of the men who “fenced the West.” Bush’s father-in-law, Joseph Glidden, invented barbed wire and sent Bush down from Chicago to buy 200 square miles of Panhandle pasture. Ostensibly, this land was to be used to demonstrate the practical value of barbed wire, but they somehow lost their patent and Grandpa Bush converted his part of the land into one of the great cattle empires. Toad Hall, the house where Stanley, Wendy, and their five children live, is located on the site and constructed from some of the same stone used in the old Bush ranch house. Stanley’s family fortune came mostly from natural gas. Stanley’s great-great-grandfather, Andrew Jackson Marsh, deserted the Union army, absconded with the maid and the church funds, and moved to Texas, where he learned the trade of water-well digging. He passed this skill down to his son and grandson, and when oil was discovered in the Panhandle around 1917 the original Stanley Marsh was well trained to get in on the ball game. In the years that followed, the Marsh family branched out into banking, cattle, television, and a number of other ventures. Stanley Marsh 3, who was always the gentle maverick of the family, dabbles in various ventures, but his main business is running Amarillo’s top-rated TV station and having as much fun as he can manage.

In a city like Dallas or Houston Stanley Marsh 3 (never III) would be passed over as another fruitcake with too much money and time on his hands, but in Amarillo, where he exercises an exceptional amount of financial clout, he is a force to be reckoned with. He lists his occupation as “capitalist” and has been known to conduct high-level business meetings with a pet lion at his feet. He wears baggy jeans, sometimes with chaps and boots, and outrageous shirts with part of the tail hanging out. He reminds you of a great, wondrous teddy bear.

Stanley is infamous for what he calls his “stunts.” He once appeared at a society wedding arm in arm with an Italian dwarf dressed like Aunt Jemima, and he showed up at the John Connally trial wearing a big hat, a polka-dot shirt, and purple chaps, and carrying a bucket of genuine Texas cow manure.

Other “capitalists” have learned to step lightly when dealing with Stanley. A developer with plans to cram ticky-tacky houses on a tract next to Stanley’s land woke one morning to discover an enormous billboard a foot away from his property line. It said: FUTURE HOME OF THE WORLD’S LARGEST POISONOUS SNAKE FARM.

Wendy Bush O’Brien Marsh, an attractive and highly intelligent woman (she has a law degree from the University of Texas), alternates between the roles of co-conspirator and stabilizing force. Only once in ten years of marriage has she vetoed any of Stanley’s proposed stunts. That was when Stanley wanted to outfit dead monkeys with skin-diving gear and hang them from the trotlines of poachers. When Stanley heard that America’s richest accused killer was coming to Amarillo, he quickly forgot about the poachers. Stanley hadn’t worked out the details, but he sensed that the Cullen Davis trial presented immense possibilities.

Judge George E. Dowlen was sometimes referred to as “the cowboy judge with the Boston brain.” Dowlen interpreted this as slander on Boston. “If I’d had a ration of brains,” Dowlen drawled, chewing on an ever-present toothpick, “I wouldn’t have agreed to take this case.” A mistrial and a torrent of news coverage in Fort Worth had forced—some would have said permitted—Tarrant County Judge Tom Cave to order a change of venue. Cave selected Dowlen’s 181st District Court in Amarillo, perhaps because he had heard that Dowlen had a reputation for maintaining his sense of humor under adverse circumstances, or perhaps because Amarillo was the closest thing he could find to Siberia.

There was no doubt Judge Cave had had more of this hot potato than he could stomach. A large segment of Fort Worth’s financial and social community was directly involved in the affairs of Cullen Davis. Early in the case Amon Carter, Jr., Babe Fuqua, and other princes of the Fort Worth power structure had petitioned Cave to grant bail to Davis, which Cave steadfastly refused. On the day that Davis was acquitted, a three-foot-tall floral arrangement from the Fort Worth National Bank was delivered to the executive suite of the Mid-Continent Building, the corporate headquarters of Davis’ worldwide empire. A card attached to the flowers read, “Hooray!” and was signed, “Bayard and Jody.” Bayard Friedman is board chairman of the bank, and Jody Grant is president.

In his two years on the bench, Dowlen had never presided over a case like this one, but then few judges had. In trying Cullen Davis, Tarrant County spent about $300,000. It was said that Davis shelled out nearly $3 million to Racehorse Haynes and his extraordinary team of lawyers and investigators. One small but revealing item on the defense budget was $30,000 for a research project to determine what type of juror would best serve Cullen’s interests.

By the time the two hundred prospective jurors arrived at the courthouse, the defense already had a thick file on each one. Potter County Judge Hugh Russell was hired to rate each juror according to information that was supplied by a battery of investigators and filtered through a computer. Russell’s former law partner, Dee Miller, was also hired as part of the defense team. In particular, Racehorse Haynes was looking for jurors who could understand the abstract notion of reasonable doubt. Although he was conducting what is called an “alibi” defense, the brilliant Houston attorney was not really concerned with establishing a hard-and-fast alibi for his client. Instead, his strategy was “to show the true colors and character” of Priscilla Davis. Racehorse knew well that the rules of evidence would not permit the prosecution to attack Cullen with the same ax. Even if Racehorse had gone temporarily mad and allowed Cullen to take the witness stand, the prosecution would not have been permitted to explore his “true colors and character.” While Priscilla was being raked over the coals daily, Cullen was able to sit before the jury looking for all the world like the head vestryman. The trial then became a one-sided morality play, an exploration of the Machiavellian workings of Fort Worth’s underbelly. The silk stockings hardly got scratched.

Of all the rulings handed down by Judge Dowlen, easily the most damaging to the prosecution was the decision to allow an array of convicted felons and drug traffickers to testify concerning their close relations with Priscilla. Joe Shannon, the assistant district attorney who handled much of the burden for the state, later said, “Most of what they [the defense] went into was the Fort Worth drug scene of 1974 and 1975. I didn’t think that was relevant and I still don’t.”

Dowlen felt that he had no choice: the veracity of the state’s key witness, the only witness prepared to say that Cullen Davis killed anyone, was subject to question, and anything less would have been a violation of the defendant’s basic rights. More than anything else it was Dowlen’s down-home sense of humor and good country temperament that brought the Davis trial to a conclusion, an accomplishment that some observers thought was impossible. “I don’t take myself too seriously,” Dowlen admitted one night at Rhett Butler’s, Amarillo’s classiest watering hole. “You just have to see the funny side of what’s going on. You can’t get much more serious than capital murder, but if you lose perspective, if people start getting uptight and lose their composure, you’re a goner.” A 43-year-old lifelong bachelor, Dowlen had lived for years with his parents in a rural crossroads called Ralph’s Switch, but he moved to the apartment complex behind Rhett Butler’s at the start of the trial, anticipating that he wouldn’t be doing a lot of sleeping for the next four or five months. “I’ve been completely absorbed in the trial,” Dowlen said. “I’ve been so wrapped up in the case that my girl friend walked out on me. I’ve had threatening letters and phone calls. Somebody mailed me a spent .38 bullet. Somebody else called and said if I didn’t let Davis out on bond, I wouldn’t make it to the courthouse the next day. That was the only time I really got mad.”

When it finally dawned on Freddy Thompson that this was real, that he was about to be locked up with eleven strangers for weeks and maybe months, and that ultimately they would have to decide the fate of a man who could buy a thousand like them out of his back pocket, Freddy tried to walk out the door. The bailiff grabbed him and read him the law. The law required that he sit in judgment. For the next 105 days, Freddy hardly spoke a complete sentence.

Freddy was a cowboy. Not a rodeo cowboy or a feedlot cowboy or a cosmic cowboy, but a genuine working cowboy. He’d never wanted to be anything else. Freddy sometimes referred to himself as a “peon,” which was easier than explaining why he preferred the company of cows. Freddy had had an occasional brush with the law. They say he once caught a deputy sheriff trespassing on the Marsh-O’Brien Ranch and felt compelled to disarm the lawman and watch him dance. Then there was the time Freddy and another cowboy named Rob turned loose that blind steer in a darkened hippie bar. But nothing serious. Freddy respected the law, and more than that he respected tradition and old-time cowboy morality. He felt uncomfortable and out of place around rich people, a possible exception being his boss, Stanley Marsh 3, whose family owned the 10,000-acre spread where Freddy worked.

Stanley was, to say the least, different. Stanley would drink with his cowboys and listen to their troubles late at night. When one of them would get cut in a barroom fight and have to run for his bloody life, he’d likely end up in the kitchen of Stanley’s ranch house where Wendy would brew some strong coffee and bring out the first-aid kit. Unlike many of the ranchers on the Great Plains, Stanley took a personal interest in his cowboys. The one gut-level thing that a cowboy wanted to know was that his boss would take care of him, not so much now, but later, when he had reaped the wretched harvest of his occupation. If a cowboy was unlucky, like Freddy’s friend Buck Ramsey, he would get crippled for life; and even if he was lucky, he was bound to wear out. For all of Stanley Marsh’s eccentricities, he was also a hardheaded businessman and for that reason had worked out a retirement plan and a good health insurance policy for his cowboys. Freddy didn’t understand the retirement plan or even want to understand it, but he believed that when it came down to it, Stanley would take care of him.

When Freddy first received his jury summons last spring, he didn’t think much about it. He’d never heard of Cullen Davis or the sensational Fort Worth murder case. Only after he had taken his seat with the jury panel did Freddy learn that the case involved the brutal slaying of a twelve-year-old girl. Freddy had a twelve-year-old daughter, and she was one of the great blessings of his life. “A twelve-year-old girl is something special,” he told Racehorse Haynes during the voir dire. Freddy said he didn’t believe in divorce, and what was more he didn’t know if he could be a fair and impartial juror. Everyone laughed when they asked Freddy his hobby and he replied: “I think it’s drinking beer.” After making that remark Freddy was fairly certain they’d send him back to the ranch. But it was late in the game. The voir dire was already into its sixth week. Freddy was the 118th prospective juror to be questioned and so far only nine had been selected. When the other cowboys heard that Freddy had been sequestered for the duration of the trial, they took bets on how long it would take for him to break out and how long it would take him to unwind enough to work cows.

Both sides knew the trial would be a test of endurance and took that into account when they picked the jury. Both sides tried to pick people who were used to listening and taking orders—a mailman, a journeyman electrician, a typist, a sheet-metal worker, a grandmother, even an ex-nun who sold cameras at a department store. “Look at them,” a Potter County attorney said. “They’re people who’ve been stomped every way but flat, but they’re good people and they’ll be fair.” Another attorney observed: “You’ll notice most of them are overweight. Overweight people are docile and submissive. They’ll hate Priscilla because of her flashy dress and her living with Stan Farr. People here don’t appreciate that sort of behavior.” I asked the attorney if that automatically meant they would appreciate Cullen. “Doesn’t matter,” he said. “Racehorse won’t let it get to that.”

While the prosecution knew they faced a test of endurance, they also knew that every day the defense could prolong the trial would be a day in Cullen Davis’ favor. It was one of those rare cases where the defendant could match resources with the state. The state was also burdened with a circumstantial case that was bound to weaken with each volley from the defense. Of all the horrendous events that took place that night at the $6 million Davis mansion, the only one without an eyewitness was the murder of Andrea Wilborn. Still, it was their best case: no Texas jury was likely to convict Cullen Davis of killing his estranged wife’s lover. The jury would therefore have to reach its verdict based on the testimony of Priscilla Davis and expert testimony that Andrea Wilborn was killed with the same .38 pistol that killed Stan Farr and wounded Priscilla and Gus Gavrel.

Briefly, Priscilla’s testimony was this: Late on the evening of August 2, 1976, she and Stan Farr returned from dinner and noticed that the security system at the mansion had somehow been deactivated. Andrea, who lived with her father, Jack Wilborn, but was spending the night at the mansion, might have unlocked the door to admit a friend, or possibly Priscilla’s older daughter, Dee Davis, had come home early. Either way, it didn’t seem that important at the moment. Farr went directly to the master bedroom upstairs and Priscilla proceeded to turn off the lights in the kitchen. That’s when she noticed the bloody palm print on the door leading to the basement. Priscilla didn’t know it, but at that moment, Andrea’s body lay in a pool of blood in the basement utility room. (Racehorse Haynes remarked that a fit mother wouldn’t have left her twelve-year-old alone, to which assistant prosecutor Joe Shannon snapped, “At least she didn’t leave her alone dead on the floor of the basement!”)

As Priscilla called upstairs to Farr, a “man in black” stepped from a hiding place and shot her through the chest. The bullet missed killing her by a fraction of an inch. Farr came running down the stairs and the man in black pumped four bullets into his six-foot-nine frame. Farr died instantly. Priscilla ran, but the man overtook her in the courtyard and forced her back into the kitchen. One can only speculate why the gunman didn’t finish Priscilla right then; Joe Shannon suggested to the jury that the killer had one final surprise for Priscilla—“he wanted to take her down to the basement and show her Andrea’s body.” While the gunman was dragging Farr’s body toward the basement, Priscilla escaped again. And again the gunman caught her in the courtyard; only this time they were interrupted by the sound of a car in the driveway. Gus Gavrel and his date, Bev Bass, had arrived unexpectedly. When the man in black turned his attention to the driveway, Priscilla ran across an open field to the home of a neighbor.

Moments later, according to the testimony of Gavrel and Bev Bass, the gunman wounded and partially paralyzed Gavrel. Bev Bass escaped—apparently the killer used his last bullet on Gavrel—and ran the opposite way from the direction Priscilla had fled. Sometime around 12:40 (there was some conflict about the exact time) both Priscilla and Bev Bass summoned help. Both identified the man in black as Cullen Davis. Later Gavrel also pointed the finger at Cullen, though the evidence was overwhelming that on the night of the shooting Gavrel repeatedly said that he didn’t know who had shot him.

Had Priscilla’s testimony been limited to the events of August 2, 1976, there is a good chance the jury would have believed her. There is also a chance they would have believed her if Priscilla had taken the witness stand dressed as Irma la Douce, openly confessing that she was addicted to the pain-killing drug Percodan, that she slept around as it pleased her, and that she selected a procession of unsavory bed partners and houseguests, included convicted felons and drug dealers, during the year between her separation from Cullen Davis and the night of the murders.

Instead, Priscilla elected to present herself as Little Mary Sunshine. The prosecution had anticipated that Priscilla might make a poor witness—they had even considered not calling her to the stand—but no amount of preparation could have prevented the slaughter that followed. Thirteen days later, when Racehorse Haynes finished his cross-examination, Priscilla had been depicted for the jurors as a woman who had not only crawled through every slimy pond in Fort Worth, but had wantonly sought them out. In his closing arguments Racehorse referred to Priscilla as “the Queen Bee, the Dr. Jekyll and Mrs. Hyde.” Bev Bass appeared to be a creditable witness until Racehorse smeared her by association with the Queen Bee who, the jury was told, lured teenage girls into drugs and sexual encounters with much older men. Weeks after the jury had heard the eyewitness accounts of what took place on August 2, 1976, they were still hearing about all the “scallywags, skuddies, and rogues” who supposedly used the mansion at 4200 Mockingbird for drug-and-sex orgies, violent encounters, and nefarious schemes against society.

What it all boiled down to was, the jury didn’t believe Priscilla when she said Cullen did it. Not “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Of the six jurors I talked to later, all used that phrase, “reasonable doubt.” One thing should be made clear: the jury didn’t say that Cullen Davis was innocent of the murder of Andrea Wilborn, just that he was not legally guilty. Titillated by tales of drugs and sex, the jurors saw days and sometimes weeks pass with no mention of Andrea Wilborn. “They never knew her as a warm, sensitive, very artistic, very private and passive person,” her father Jack Wilborn said later. “The jury was left with the impression that Andrea loved Cullen. In fact she was terrified of him. She refused to go anywhere near the mansion as long as Cullen lived there.” What the jury came away with was a sense of sympathy for Cullen Davis, whom they saw as a well-bred establishment figure being framed for his own good intentions.

James Watkins, one of the first jurors selected, told me: “I think maybe sometimes Priscilla didn’t lie to us, but she didn’t tell us enough of the truth to believe everything she had to say.” Another juror, Karl Prah, confirmed that had Priscilla been more open about the details of her private life, “there would have been a lot more weight to her testimony” regarding the real issue—who killed Andrea Wilborn. Watkins added, “It’s possible that Cullen could have done it, but we had the doubt that he did it. The reasonable doubt is what I think brought the verdict.” I didn’t have a chance to talk to Freddy Thompson after the trial. The split-second that Judge Dowlen told the jury they were dismissed, Freddy literally leaped out of the jury box and disappeared.

Within an hour after the reading of the verdict, four of the jurors had joined Cullen Davis’ victory party at Rhett Butler’s.

I couldn’t blame them. They must have been curious. Through the many weeks of their ordeal, they had never heard a word from the mysterious millionaire defendant, had never seen him take a drink or order from a menu or walk across a room or do any of the things that real people do. All they knew about Cullen Davis was what they had been told by his attorneys, friends, and associates. The only trace of scandal that had come to their attention was when Karen Master admitted that Cullen had shared her bed at the time of the murder. Karen was his alibi. She went to bed early on the night of the killings, so she couldn’t say for certain what time Cullen got home. He told her later that it was about 11 p.m. But she remembered waking at exactly 12:40 a.m. and finding Cullen asleep beside her. This would have been roughly the same time that Priscilla and Bev Bass were calling for help. For reasons that were never clearly explained, Karen didn’t tell this to the police or to the grand jury or to the authorities conducting the bond hearings.

Karen Master was an object of enormous fascination, possibly because it was so difficult to assess her role in these bizarre happenings. Karen had a doll-like prettiness that made it impossible to imagine her getting dirty. Certainly she had known her share of earthly pain and grief—an automobile accident a few years ago permanently disabled her two young sons, and Karen herself was almost killed. “It taught us all a great deal,” she recalled, smiling sweetly when she recounted the terrible experience. And, of course, there was the ordeal of the Cullen Davis affair. Except during her brief testimony, Karen was not permitted in the courtroom, but day after day she waited outside and people marveled at her composure, at her unshakable faith that all things would turn out well. Karen’s very presence in Amarillo gave force to a certain twisted logic in defense of the man she loved. The wife of a local attorney, who specialized in education for the handicapped and had worked with Karen’s youngest son, told me: “I know Cullen didn’t do it, because I know Karen Master. She is a wonderful mother. A woman like that wouldn’t live with a killer.” Karen was highly popular with the press and could frequently be seen dancing at Rhett Butler’s or the Caravan Club, a model of fashion in suede and leather, drinking pink icy drinks and wearing a smile so sweet and sad it seemed painted permanently on her face.

It was difficult to explain why the same people who thought Priscilla so shameless for bedding down with assorted characters saw nothing wrong with Cullen shacking up with Karen, unless it was for the fact that Karen is roughly ten years younger than Priscilla. When Karen told her story to the jury, she was almost a caricature of sweetness and composure, listening attentively to each question, then turning in exaggerated slow motion and smiling to the jury as she answered. “We didn’t believe her, but it didn’t matter,” Michael Giesler told me. “We still had reasonable doubt Cullen did it.”

The jury never heard it, but Cullen did supply his alibi for the press. On August 2, 1976, Cullen maintains he worked late, ate alone, and went to a movie. He got home about midnight. One night after the acquittal, someone finally asked the pregnant question. Cullen, his entourage, and some newspeople had been talking about who should play Cullen in the movie version of the story—Cullen favored Al Pacino—when AP writer Mike Cochran asked out of the blue, “By the way, Cullen, what movie did you see that night?” There was a long, bone-chilling silence while Cullen seemed to slip into a trance; then he answered coolly, “That will have to wait for the next trial.” But of course everyone knew there wouldn’t be a next trial, not for the events of August 2.

Cullen’s victory party at Rhett Butler’s was a sight even for these jaded eyes. The only thing I can compare it to is the Cowboys’ dressing room when Dallas won the 1972 Super Bowl. There was hugging, kissing, laughing, crying, toasting, and a good word to say about nearly everyone. With the obvious exception of the prosecutorial team, the whole cast turned out—judge, jury, bailiffs, press, Cullen’s bodyguards, even a few select groupies. To express his appreciation, Cullen picked up the $650 tab. In the glaring lights of TV cameras, Cullen and Racehorse did the kind of number you would expect from a couple of rookies who had just combined on the winning touchdown. They danced around each other talking jive, slapping palms, and bumping asses.

Racehorse, who had been remarkably subdued during the long trial, was like an order of skyrockets that afternoon. He was the Vince Lombardi of trial lawyers: he hated to lose, but God did he love to win. During the course of the trial I had formulated what I would call my “wino-with-terminal-cancer hypothesis.” He would be Racehorse’s final bombshell witness; he would cough and gasp, “I done it,” then fall dead on the courtroom floor. This wasn’t as absurd as some people thought. Racehorse had once remarked: “I continue to dream of the day when I am cross-examining a witness and my questions are so probing and brilliant that the fellow blurts out that he, not my defendant, committed the foul murder. Then he will pitch forward into my arms, dead of a heart attack.”

Nothing half that clean had happened in the Cullen Davis case. But Racehorse had worked like fifty demons. He’d even given up drinking for the duration of the trial. He lectured me one day on the evils of the devil’s tonic, claiming that it rotted away beta cells and thus destroyed the brain’s memory bank. “The trouble is,” he grinned, “when you give up the juice you start remembering what it was you started drinking to forget.” A couple of hard scotches must have jiggled the old memory bank because Racehorse was letting it all out at the victory party.

Then, in an incredible display that I’m sure he later regretted, Racehorse went before the live TV cameras and talked about Priscilla. In an evangelical crescendo, he proclaimed: “She is the dregs. She’s probably shooting up right now. She is the most shameless, brazen hussy in all humanity. She is a charlatan, a harlot, and a liar. She is a snake, unworthy of belief under oath. She is a dope fiend and an habitué of dope. She is the most sordid human being in the United States, in fact the world. Someone ought to put up a barbed-wire fence around her and keep her there.”

When I had drunk all of Cullen’s whiskey that I wanted, I went back to my hotel and telephoned Priscilla in Fort Worth. She was alone at the Davis mansion. She had already heard the verdict and she had been crying for several hours, but having someone to talk to helped, and she began to compose herself and prepare for whatever would come next. A friend of mine once remarked that Priscilla was “like a cockroach,” but he didn’t mean it cruelly. It was the same sort of remark that the Amarillo attorney made about the jury: they’ve “been stomped every way but flat.” There are some people who, by training or instinct, will always get up and keep going. Still to come was the divorce trial, where the rules would be different. Cullen would have to take the stand. Possibly more about his true colors and character would yet come out. The murder trial had ended, but many things remained to be resolved, including possibly millions of dollars in the divorce settlement and a number of civil suits filed in connection with the shootings. Priscilla was a long way from packing her bags. She might, as Cullen had said, end up in Waco working in an all-night donut shop, but I wouldn’t bet on it.

On the phone, Priscilla said she didn’t blame the jury. “I put myself in that jury box many times,” she said. “If I had listened to that many people tromping through the courtroom saying the things they said about me and nobody bothering to refute any of it . . . I might have come to the same conclusion.”

I couldn’t think of anything to say. There was a long, hurting silence, then Priscilla said: “It looks like everyone won today except me. It cost Cullen a lot and it cost the state a lot, but it cost me a child that I loved very much. That’s the part that nobody wants to talk about.”

If Priscilla was not telling the truth about who shot her, then she has to be covering for the person who really did. The jury apparently found that easier to believe than I do.

In terms of wealth and power Cullen has few peers, but certainly Stanley Marsh 3 is one. They are both sons of wealthy oilmen, self-styled hard-nosed capitalists, men of carefully defined tastes, and connoisseurs of great art. Cullen prefers the brooding, elegant (some would say pompous) paintings of nineteenth-century Europe. In the words of one critic, they hung on the walls of his mansion “like certificates of stocks and bonds.” On the other hand, Stanley conceived of art as “a system of unanticipated rewards.” One of his most famous commissions stands in a pasture along Route 66 just west of town. As motorists top the crest they are astonished to see ten Cadillacs nose down in concrete sheaths at the exact angle of the Great Pyramid. Other art objects, such as the “World’s Largest Phantom Soft Pool Table” and the nationally known “Amarillo Ramp” lie miles from the nearest road, unanticipated rewards for roving cowhands, passengers of low-flying aircraft, or refugees from long-lost wagon trains. Cullen liked to tell friends, “I don’t understand art. I buy what I like.” He once walked into a gallery in New York and liked 115 paintings and bronzes so much that he purchased them on the spot. Stanley isn’t that impulsive. None of Stanley’s art is fit to hang in a gallery, but if you were to ask him what art is, he would point proudly out the back door of Toad Hall—there, among the grazing zebras, yaks, llamas, and rheas, brightly painted letters six feet tall spell A-R-T. That’s what art is.

I had read and heard a great deal about Stanley Marsh 3, but until I met him I never realized what crazy things a man has to do before he’s truly sane. We became instant friends, sharing, as we did, a passion for expensive Cognac and cheap talk. Two or three nights a week we would sit in the kitchen at Toad Hall, and after Wendy and the kids had gone to bed, Stanley would break out another bottle of Courvoisier and we’d go on for hours about books and friends and the science of life. There was a rather touching moment one evening when Stanley recalled his favorite drinking partner, Minnesota Fats. Fats was a 400-pound pig with wings tattooed on his sides. Long before my arrival in Amarillo, Stanley and Fats would wile away the evenings drinking Mateus, but Fats OD’ed and, until I hit town, Stanley seemed a bit maudlin.

Stanley enjoys the company of writers, artists, and politicians, and each day at noon a motley group would gather in his office for what Stanley called his daily “picnic.” Stanley’s office was atop the tallest building in Amarillo—the tallest building between Dallas and Denver, in fact; there we’d discuss the trial and conjure plots. Hugh Russell, the county judge who was instrumental in helping the defense select a jury and an old friend of Stanley Marsh, spoke of the inadequate security, and that naturally gave birth to a scheme to snatch Cullen, crate him in cedar, and ship him to South America where, under more graceful and leisurely surroundings, he would no doubt reward us handsomely. Russell revealed that Cullen had nearly been the cause of a real jailbreak. Absorbed by the theatrics in Judge Dowlen’s court, a deputy had accidentally left a convicted murderer alone in a corridor.

“Why didn’t he escape?” Stanley asked.

“I guess he wanted to wait around for Cullen,” someone said.

Stanley would stand at the window on the thirtieth floor looking across at the Cullen Hilton. He’d put his thumbs in his baggy jeans and ask, “What’s Cullen really like?”

“I don’t think anybody knows,” I told him.

“Do you think he did it?”

“I don’t think the jury thinks he did.”

“My sister-in-law doesn’t believe he did it. She doesn’t believe wealthy husbands shoot their wives.”

Stanley would remove his thick glasses and clean them on the tail of his shirt, and you could tell he wanted to do something. Cullen was too rare to pass up. Cullen probably even expected something: Stanley was sure of it. Second-generation rich share a feeling that they are not bound by normal rules of society, and so it was with Cullen and Stanley. Among the Fort Worth establishment Cullen was celebrated for his temper tantrums, his taste for ostentatious extravagances, and his high tolerance for pornography. By contrast, Stanley practiced what Camus called “lyrical inhumanity.” Buck Ramsey, who grew up with Stanley, explained: “Stanley can be cruel, like telephoning Gus Mutscher in the middle of the night and asking for a loan from Sharpstown, but Stanley keeps it on a lyrical level.”

When Cullen was briefly freed on $1 million bond, Stanley seized the opportunity: he telephoned every airline in town and reserved one-way tickets in Cullen’s name to Rio de Janeiro. Somewhere around the seventh week of the trial Stanley decided to move his phantom soft pool table to the roof of a building across from the Cullen Hilton. This gave birth to a strange rumor that Stanley was in cahoots with Racehorse Haynes and together they were sending secret messages to Cullen in his jail cell. When a local newspaper columnist called and asked if the rumor had any veracity, Stanley admitted that it did. This quote from Stanley appeared the following day:

“Since Cullen’s cell points east [the soft pool table was west of the jailhouse], he loosens the bars from his cell, escapes [by] climbing to the courthouse roof from where he can see the soft pool table, reads the message and then secretly returns to his cell . . . ”

I’m not certain how Cullen reacted to all this, but when Stanley made a rare visit to the courthouse a few days later, Cullen asked to meet him. I asked Stanley what they talked about. “Skinny-dipping,” Stanley told me. “I asked Cullen if he knew anything about skinny-dipping and he said he could tell me all I wanted to know. He went into great technical detail about how to arrange the lights for maximum privacy.”

On Saturday night, two days after the trial ended, Stanley threw a party at Toad Hall. He invited the whole cast, including Cullen and Karen Master. Cullen appeared far less jubilant than he had at the victory party. Too long he had been a martyr: now he conducted himself with the quiet dignity of a hero. Stanley was fairly licking his chops as he zoomed in on the ex-accused murderer. Cullen didn’t seem particularly interested in discussing art or seeing Stanley’s two tattooed Chinese hairlesses, so Stanley asked him about Priscilla. If she was such a hussy and harlot, why had Cullen married her? Stanley told me later: “Cullen told me she changed [for the better] after they were married. But when Fort Worth society refused to accept her, she went back to her old ways. Well, I told him, a tiger can’t be expected to change her spots. Cullen corrected me. He pointed out that tigers have stripes.”

I wondered what Stanley thought of Cullen now.

“Let me put it this way,” Stanley said. “I don’t think Minnesota Fats would have enjoyed drinking with him. If I had to think of one word for him, it would be creep.”

“Can I quote you on that?”

“I insist,” Stanley said.

The last of the circus pulled out of Amarillo the morning after Stanley’s party. There were a lot of sad farewells, as there are at the finish of any ordeal. There was television footage of Cullen and Karen shaking a lot of hands as they boarded his Learjet. Cullen promised that he would be back at his desk Monday morning. Racehorse Haynes had already departed for Boston, where he was scheduled to make a speech. Joe Shannon, who had performed exceptionally well for the losing team, had lost 35 pounds during the trial; he felt good about that at least. But when he boarded the plane for Fort Worth and realized he had exactly eighteen cents in his pocket, he couldn’t help smiling at fate. The press returned to their home posts to resume their customary fare of car wrecks and honky-tonk stabbings, all except Evan Moore, who resigned his job at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram to become a cowboy in Happy, Texas. Judge Dowlen patched things up with his girl friend and went back to work on his badly neglected docket. The groupies went to work on their scrapbooks, but the majority of Amarillo began forgetting Cullen Davis. Most of the writers and artists had gone, but when bankers and lawyers and politicians met at Stanley’s office for the daily picnic, someone always said, “Don’t tell me any more Cullen Davis stories.” There was plenty of local scandal to occupy them. The county attorney, the sheriff, and a sheriff’s captain were all being investigated for unrelated misdeeds. Stanley was drafting plans to have 500 acres of wheat mowed into the shape of a giant hand—the “Great American Farmhand,” he would call it.

Two weeks after the trial Stanley still hadn’t located Freddy, his missing cowboy. Then one night in December, at 3:22 a.m., Freddy appeared in Stanley’s bedroom and shook him by the toe.

“He had crawled in through the doggy door,” Stanley said. “He was covered with frozen mud and had a glass of whiskey in his hand. He wanted to know if I thought he’d done the right thing in acquitting Cullen. He was apparently taking some ribbing from the other cowboys. I told him I didn’t know. I thought Cullen probably did it, but I also thought the state didn’t prove its case. I told him that if I had been on the jury, I’d probably have voted the same way. That’s all he wanted to hear. He went home.”

The following morning Freddy was back at work with the rest of Amarillo.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Stanley Marsh 3

- Amarillo