One afternoon last summer, I pulled into the parking lot of R.C. Loflin Middle School, in Joshua, a town south of Fort Worth, where thirty or so people had gathered. Many of them wore T-shirts inscribed with slogans such as “Stop the Violence” and “You Must Be the Change You Wish to See in the World.” A few held signs that read “Stand for the Silent.” Almost everyone was milling around a wobbly folding table, staring at framed photographs of about 25 good-looking, smiling children and teenagers from around the country who had recently committed suicide. Prominently displayed at the front of the table were photos of fifteen-year-old Hunter Layland, from the nearby town of Cleburne, who had shot himself before school on September 30, 2009; Montana Lance, a nine-year-old from the Colony, near Lewisville, who had hanged himself in the bathroom at the nurse’s office in his elementary school on January 21, 2010; and Jon Carmichael, a Joshua teenager who had attended this very middle school and who had been found hanging in a barn behind his home on March 28, 2010.

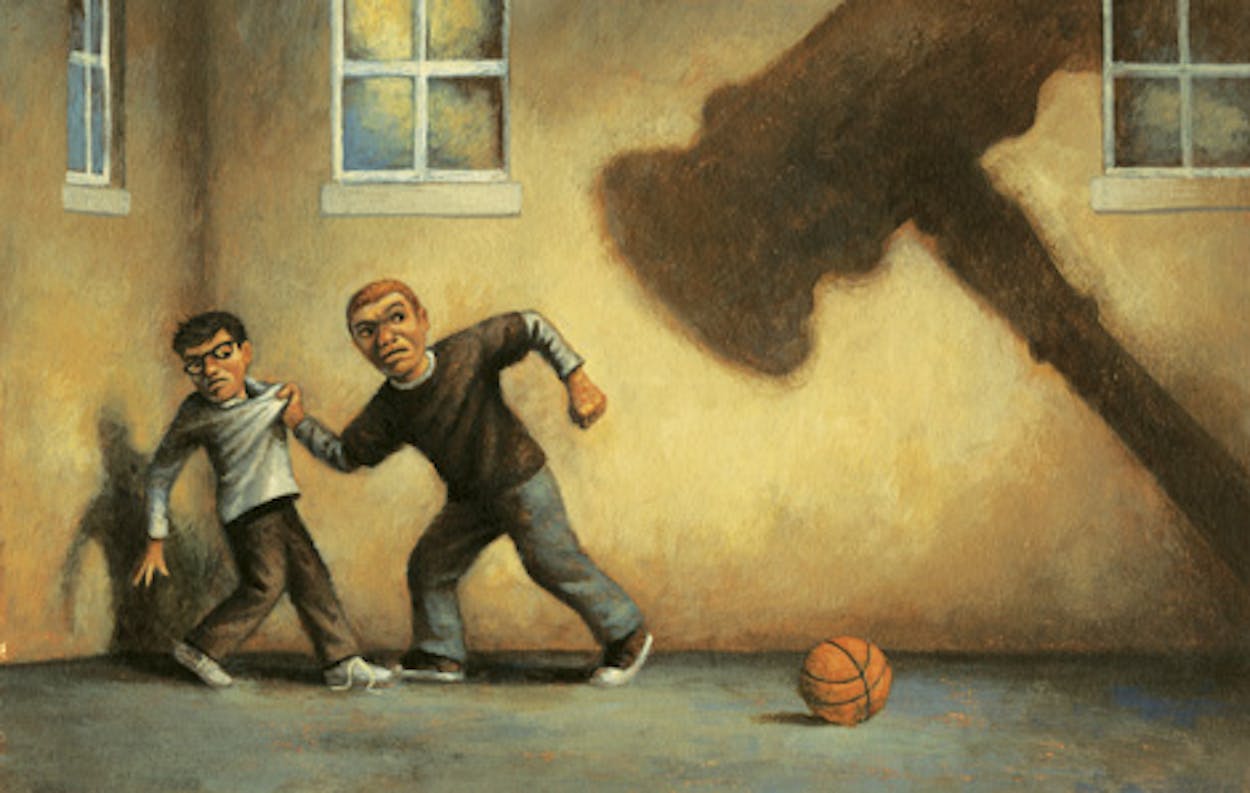

Like every other kid in the photographs, the three boys had killed themselves after years of taunting and bullying by school classmates. “Hunter was teased almost all his life because he had hearing problems and a scar on his face, which he got in a car wreck when he was just a toddler,” his mother, Melanie, told me. “One boy used to tell him that if he had a face like that, he’d shoot himself.” Debbie and Jason Lance, who were standing near the table wearing pink T-shirts that read “The Bullying Stops Here,” said that Montana had been bullied since the second grade because he had a speech impediment and was prone to emotional outbursts. “The kids called him gay and refused to sit with him at lunch,” Jason said. “He would ask his teachers if he could stay inside rather than go out to recess, where the kids hit him and pushed him around. But the teachers always made him go out to the playground. Finally, to get away from the boys, he started saying he was sick so he could be sent to the nurse’s office.”

A few minutes later, Tami Carmichael, whose T-shirt was emblazoned with the image of her son, walked up. She told me that for reasons no one quite understood, Jon became the target of the popular, athletic kids at school. “He was pushed to the ground on an almost daily basis. They’d throw him in the school’s dumpster a couple times a week, and they stuck him head-down in a toilet and started flushing,” she said. “One day they stripped him naked, tied him up, and stuck him in a trash can, and they taped it with their cell phones and put it all on YouTube.”

That was a day or two before Jon, a small kid with a mop of brown hair, had slipped out to the barn. “We didn’t know where he had gone until my husband went to feed our horse,” Tami said. “And then I heard my husband make a sound I had never heard him make before. He started shouting, ‘No, Jon, no!’ I ran out and saw Jon with a belt around his neck, hanging from a rafter, and I saw my husband struggling to push him up so he could breathe. I climbed a ladder to undo the belt. But by the time we got Jon down, he was already cold.”

The three suicides—which took place within a span of six months—would be followed by another that fall. In October, Asher Brown, a Houston eighth grader and straight-A student, shot himself in the head after classmates performed mock gay sexual acts on him in gym class and ridiculed him because he was a Buddhist who didn’t wear designer clothes. The students’ deaths, which appeared to coincide with other “bullycides” around the country, such as that of Rutgers University freshman Tyler Clementi, sent shock waves across Texas. Front-page newspaper stories detailed the modern-day perils of bullying; activists held rallies against the harassment of gay students; TV outlets debated the effects of online abuse, or cyberbullying; and state legislators vowed to propose laws that gave schools greater authority to stop bullies.

What was not reported amid all the noise and soul-searching was that each of the Texas families who had lost a son quietly met with a little-known lawyer named Marty Cirkiel. He asked if they would let him do something that had rarely been attempted, in Texas or the country: sue their children’s school districts for allowing the bullying to have occurred in the first place.

Marty Cirkiel is a 61-year-old former social worker with a salt-and-pepper beard who usually wears jeans, a T-shirt, and work boots to his office in Round Rock, outside Austin. A native of New York, he came to Texas with his wife in 1981, spent several years working in a state mental-health outpatient center, and then enrolled in St. Mary’s University School of Law, in San Antonio. After graduating, in 1992, Cirkiel specialized in juvenile law and Child Protective Services cases, and periodically he’d be hired by a family with a special-needs child to file an administrative complaint with the Texas Education Agency against a school district for not providing required services to that child. “What stunned me was how many of the families’ complaints were about their kids’ getting bullied,” Cirkiel recently told me. “One kid had pencils stuck up his rectum. Another was burned and branded with a heated paper clip. A boy with autism was sexually assaulted. I thought times had changed, that kids were more accepting of other kids. What I realized was that there was more pressure than ever on those who did not fit in. And I also realized that almost no one was doing anything about it.”

Bullying, of course, has been around forever, a survival-of-the-fittest reality on the playground that for many—particularly in Texas, where frontier tradition dictates a fight-or-die outlook on the world—is a rite of passage. (A Houston Chronicle story in October generated dozens of online comments about how bullied kids simply need to learn to fight back.) Yet if statistics are to be believed, bullying does appear to be increasing. Data compiled by the National Center for Education Statistics in 2007 showed that nearly a third of students between the ages of twelve and eighteen reported having been bullied at school; last year a study by the Josephson Institute of Ethics found that 43 percent of teenagers said they had been physically abused, teased, or taunted in a way that had seriously upset them. Compounding the issue is the modern-day phenomenon of cyberbullying, which grants an abuser anonymity while eliminating a victim’s ability to fight back or hide. Cruel words are no longer restricted to the wall of a school bathroom; fake photos and lurid rumors now spread across the Internet in seconds, never to be erased.

Like other states, Texas mandates that school districts prohibit bullying and harassment in their student codes of conducts; districts are also required to address bullying in their “discipline management plans.” But there is no law that requires a district to implement comprehensive anti-bullying programs, assign counselors to victims, or require teachers to undergo training for how to deal with bullies. This spring, emboldened by last year’s deaths, lawmakers in session at the Capitol introduced more than fifteen anti-bullying bills, including one called Asher’s Law. The proposals ranged from granting districts the unprecedented power to transfer bullies out of their schools to giving administrators the right to investigate off-campus cyberbullying. In late March, the Carmichaels, the Lances, and the Truongs (Asher Brown’s mother and stepfather), accompanied by Cirkiel, appeared before the Senate Education Committee to beg for change.

But because of civil rights objections (monitoring students’ extracurricular Internet activities amounts to an invasion of privacy) and the state’s budget crisis, the bills lack teeth. In an anti-bullying proposal presented by Fort Worth senator Wendy Davis, for instance, it was merely recommended that districts include teacher training. “Let’s be honest,” Davis told me. “Teachers have studied how to teach, not how to deal with bullies. But we have no money to fund such training. So all we can do is suggest that districts set them up.” Some bills do propose that when a school staffer hears about bullying, he or she must immediately inform the principal, who must notify the parents of the alleged bully and the victim within two days. The principal must then investigate the matter within a reasonable time frame. But because state law has no clear definition of bullying—is it one boy taunting another or is it physically beating him?—there is plenty of wiggle room for educators to decide if a student is actually being harmed. (As these pages go to press, no new anti-bullying legislation has been passed.)

That is where Cirkiel comes in. “The fact is,” he told me, “at the end of the day, no law created by a state legislature can do what a federal court can do.” As he sees it, schools will not enact change unless they get a wake-up call in court. In 2010 he filed federal lawsuits against three districts for continually allowing bullying. The first was the Tarkington district, near Houston, for neglecting to respond to bullying complaints by a boy with Asperger’s syndrome who later became suicidal. The second was a district in the McAllen-Harlingen area, for allowing a special-needs teenager to be tormented so viciously—at one point he was supposedly held down while another boy forced his penis into his mouth—that his parents had to homeschool him. The third was the Marion school district, near San Antonio, in which a boy with special needs was ridiculed by teachers who believed he was fabricating stories about being bullied.

But it wasn’t until this year, when he filed federal lawsuits in January, March, and April on behalf of the Lance, Carmichael, and Truong families, respectively, that Cirkiel started getting media attention (the Layland family decided not to sue). In his lawsuit for the Lances, he lashes out at school personnel for turning their backs on their own anti-bullying policies and ignoring Montana’s and his parents’ pleas for help. His case for the Carmichaels alleges that the Joshua school district “clearly had an actual practice and custom of looking the other way” when informed of bullying incidents involving Jon. And his lawsuit for the Truong family claims that the Cypress-Fairbanks district may have “destroyed or withheld” evidence, including videos, proving that Asher had been severely harassed.

Cirkiel does not have to be told that it is next to impossible to win a case against a school or a school district in federal court based on claims of damages to a child. The schools are almost always given immunity from such lawsuits unless a plaintiff can prove that educators are deliberately indifferent or failing to follow their own policies. Just last year, one federal appeals judge declared that a district should not be held liable for a student’s attempting to commit suicide. What’s more, even if they have good cases, plaintiffs are rarely awarded monetary damages.

But Cirkiel’s quixotic quest is fueled by what he describes as a student’s “absolute, constitutional right to pursue life, liberty, and happiness, which doesn’t exactly happen when you are terrified about going to school.” When he began filing his administrative complaints a few years ago for special-needs students, almost all the cases led to settlements, with school officials promising to offer more services and protection. But bullying complaints kept coming in from around the state. “It’s not that administrators don’t want to make their schools safe,” said Cirkiel. “They all talk about their zero-tolerance approach. But they simply are not on top of the problem. They tell me they haven’t received any bullying reports. Or they’ll say they can’t verify a bullying allegation because no other kids are willing to talk about it. They still have a passive approach, and as a result, the meek and disadvantaged kids get harassed. Instead of exploding outwardly like the two teenagers at Columbine High School, these kids are exploding on the inside, ready to give it all up.”

So far, only the Lewisville district, where Montana attended classes, has responded to Cirkiel. Its lawyers have declared in a court filing of their own that Cirkiel’s stated reasons for Montana’s suicide are purely speculative, that there is no evidence that teachers or administrators acted indifferently or put him in any danger. And as for Montana’s constitutional right to life, liberty, and happiness, the lawyers argue, it is on Cirkiel to prove that a school official knowingly violated it—which they insist he is unable to do.

Cirkiel openly acknowledges that his lawsuits might get thrown out of court. (Of the handful of other bullying lawsuits from Texas filed in federal courts, none have gone to trial.) “But we’re not going to stop fighting,” he said. “We’ve set up a website for families in Texas, and so far more than seventy have called or filled out referral forms. So one day we’re going to get a chance to make our case before a judge or a jury, to prove that a school district knew a kid was being bullied and did nothing about it. If we can just get to trial, I’m convinced a lot of districts will finally get their act together. Otherwise, I want them to know that we’ll continue to come after them.”

When Tami Carmichael appeared in March before the Senate Education Committee, she hoped to speak convincingly about how new anti-bullying laws might have saved her son. But when the moment finally came, she burst into tears, staggering dramatically out of the room. In the same hearing, Cirkiel, who wore a suit for the occasion, tried to impress upon the politicians just how deadly an issue they were facing, going so far as to describe bullying as “the equivalent of torture.”

A couple of weeks later, I drove to Joshua again to see Tami. It was exactly one year after Jon’s suicide. She was sitting on the front porch of her daughter’s home, looking at photos of Jon. “I thought some of the grief would go away, but it’s only gotten worse,” she told me. “We’ve never received a phone call from anyone at Jon’s school, we’ve never gotten a visit, and we’ve definitely gotten no apology. Every time I go into town and see one of Jon’s teachers or coaches, they turn their heads. I heard they have been told not to talk to me because of the lawsuit. It’s like they’re trying to pretend that we don’t exist anymore.”

She stared at the images of her son. “One day I’d like to take everyone from Jon’s school out to our barn and show them where we found him hanging. And then I want to ask them, ‘Was it worth it to let some kids have their fun with my son? Was it worth it?’”