This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

At precisely 5:15 on a soupy Monday morning in October, Bill Yeoman, head football coach for the University of Houston, stepped out of his large brick home on the ninth hole of the Sugar Creek Country Club and into his shiny new Buick Regal. A tall, squarely built man of 57, Yeoman walked with the sure step he had acquired 35 years earlier at West Point. Humming softly to himself, he sparked the car to life and punched on the car radio: “ . . . and when Jesus returned, the crowd welcomed him . . .”

Yeoman pulled out into the street, past the guardhouse, the white pillars, and the sparkling fountains that marked the entrance to his expensive subdivision, then turned east onto the Southwest Freeway toward downtown Houston, seventeen miles away. Taped to the dashboard was Yeoman’s schedule for the previous week, typed on a sheet of stationery with a red “Home of the Cougars” letterhead. Under “Saturday,” it read, “Beat Baylor!!!!!!” Unfortunately, Yeoman’s team had not beaten Baylor, but had lost 24–21. The defeat dropped Houston’s record to one win and three losses, and now the team had to prepare to play Texas A&M in College Station.

The coach drove rapidly through the darkness, passing the glitzy shops and hotels of the Galleria and the clutch of office towers at Greenway Plaza. Near downtown he turned south onto the Gulf Freeway, and suddenly the scenery changed. Barely visible from the light of streetlamps were broken-down shacks and trash-strewn lots, the slums of Houston’s black Third Ward. Yeoman exited the highway and turned right down Cullen Street toward the UH campus, where the hulking mass of a darkened football stadium loomed in the distance.

Arriving at the one-story Harry Fouke Athletic Building shortly after five-thirty, Yeoman pulled into his reserved parking space and bounced out of the car. He unlocked a fire-engine-red door, fetched a cup of coffee from a lounge, then crossed over to another building. Yeoman entered a disheveled conference room littered with old football programs and discarded newspapers and settled down at the end of a long wooden table. He picked up a yellow-encased spool of film, threaded it into a waiting projector, and flipped on the machine. Blurry figures in football uniforms appeared in a small rectangle on a screen. Yeoman stared at the picture, then rubbed his fists in his bleary eyes. Finally, he adjusted a dial on the machine, and the images sharpened. “And behold,” Yeoman said, “there was light. . . .”

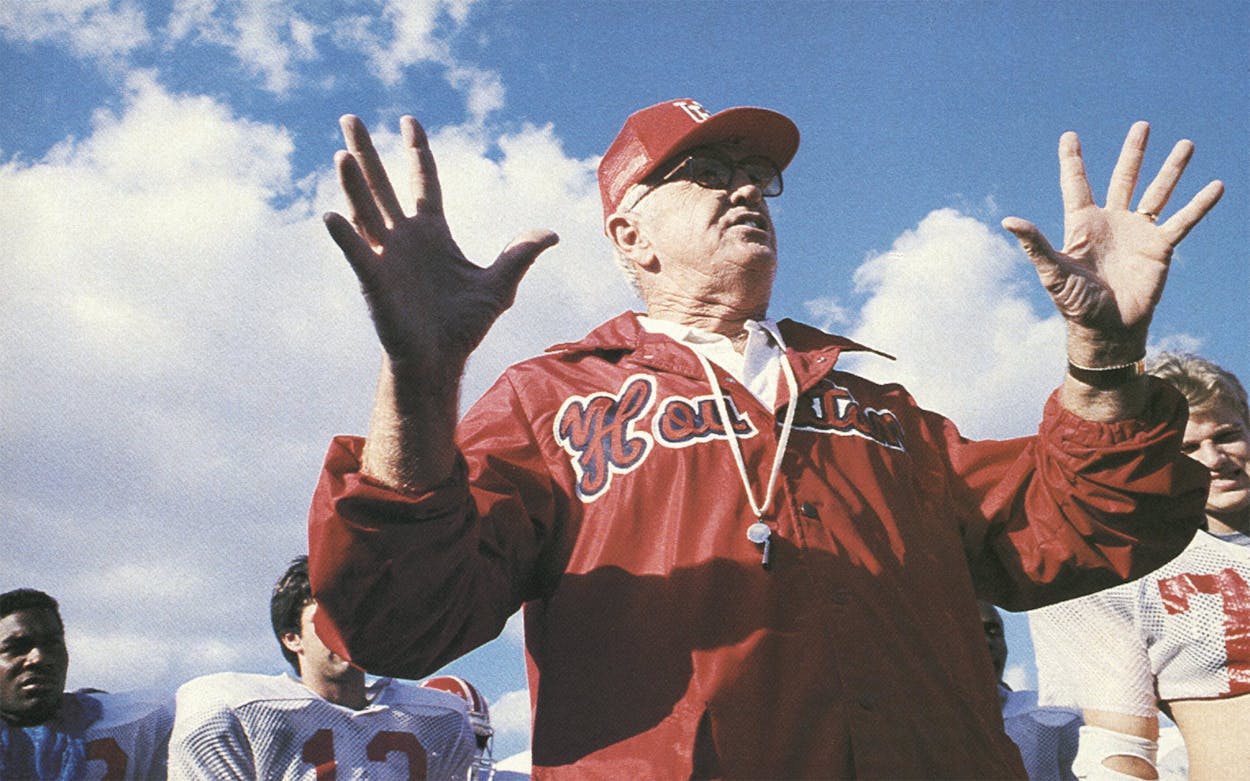

The football coach is one of the great masculine figures in our culture—a role model for youth and an advocate for the notion that football is more than a game. I spent a week this fall with Bill Yeoman because he is the quintessential coach. Yeoman regards football as a metaphor for life, his athletes as surrogate children. He speaks in the clichés of sports, believes in God and rigid discipline, and addresses everyone as “coach.” He has preached the same offensive gospel for two decades. He does not cheat to get his players. In a day of justified cynicism about big-time college athletics, Yeoman is refreshingly old-fashioned.

He has also been remarkably successful. Bill Yeoman has coached at the University of Houston for 24 seasons—longer at one institution than any other head football coach in the country. Through the 1984 season Yeoman had won 155 games—more than all but three other active coaches. His school attracts far fewer blue-chip high school athletes than the University of Texas, SMU, or Texas A&M; it has fewer fervent alumni, worse facilities, and a less-heralded tradition than every one of its eight Southwest Conference rivals. Yet in the nine years Houston has competed for the SWC title, UH has shared or won it outright four times.

For a coach, who must depend on the raw, undeveloped talent left behind by his high-powered rivals, life is invariably a roller coaster. In 1984, after two uninspired seasons, it was widely rumored that Yeoman would be fired at year’s end. Instead, he took his team to the Cotton Bowl and was rewarded with a four-year contract extension and a $28,000 raise. But if 1984 was an exhilarating surprise for Yeoman, 1985 was to be a trying experience. He had many undisciplined young players who were struggling to cope with the college classroom and life away from home.

Yeoman has thrived in that uncertain world through some luck, a lot of success, and a placid temperament. He steps adroitly through the land-mined turf of overzealous boosters, illegal recruiting, university politics, and unpredictable young athletes. He has been assailed by boosters who want to fire him for being old-fashioned and by rival coaches who demean his university as Cougar High, the ghetto school. “I’ve lasted because I’m positive,” says Yeoman. “When they drove nails through the most perfect man on earth, I quit worrying about what they do to me.” Ultimately, like all who claim the title of coach, Yeoman must depend on his ability to impart wisdom to a collection of youths in the five days before each Saturday’s game. He survives by keeping his eye squarely on the ball; every week is a new ball game.

Monday

“Friggin’ Aggies!” Bill Yeoman shook his head in the darkened projection room as he replayed the film of an A&M tackler slamming illegally late into a punter. “It’s just kind of an Aggie mentality. They just go lunging around.”

At seven-thirty Yeoman left the game films behind for the short drive to the athletic dormitory, where he ate breakfast every Monday morning at the training table. He pulled into the service entrance of the cafeteria and stopped his car directly in front of a No Parking sign. As he walked through the kitchen, food workers wearing red UH caps smiled at him and waved. In the brightly lit dining room a handful of football players, dressed in gray T-shirts with the words “Think Cotton” emblazoned in block letters, were already moving through the serving line. The rest of the team would be there later; Yeoman requires his players to get up for breakfast.

The coach filled his plate with food and sat down with his assistant coaches at a round table in front of a sign reading, “Houston Defense: You Got What It Takes.” The sign has turned out to be wishful thinking. With few returning starters, Yeoman’s inexperienced defense had been porous lately, giving up more than four hundred yards a game. But defense is a problem Yeoman delegates to his assistants; he is an offense-minded coach, and he spends most of his time working on strategy for attack.

Yeoman finished breakfast but made no move to leave. “We’ll set around here and wave to ’em,” he said, tapping on the table in time to the soul music blaring over a loudspeaker. “You gotta be seen. These kids don’t see as much of their parents as I did.”

Yeoman takes his role as surrogate father seriously. He treats his players with a mix of cajoling and blunt discipline. He is one of the few head football coaches who still conduct bed check; players must be in their rooms at eleven. Until last year players were not allowed to wear any facial hair; now he allows only neatly trimmed moustaches. Yeoman expects players to show up for class. His assistant coaches conduct spot checks, and those who are not in attendance are required to run laps at six the following morning. And he has conducted mandatory drug testing for years.

“I was in China this summer,” he said. “I’ve heard that anybody caught with dope there is beheaded in public. So it takes about thirty seconds to get the message across. If we’d go ahead and behead the pushers, it’d be a little tight for a while, but I bet we’d get control of it in a limited amount of time.”

Yeoman got up to leave. He was dressed in a gray V-necked sweater, a white shirt, blue beltless slacks, and tasseled loafers. The coach stands two inches over six feet and is close to the one hundred ninety pounds he weighed as an All-American center for Army. He has a deeply creased face framed by large ears and silver hair. On his right hand he wears a gold ring with the letters “UH” spelled out in tiny diamonds; on his left, his class ring from West Point and a souvenir from the previous season’s success—a Cotton Bowl watch.

“You know what’s really terrible?” Yeoman told a trio of assistant coaches back in the film room. “We’re playing better right now than we did a year ago. That’s what drives you up the friggin’ wall.” His team’s problem was mental errors: fumbles, interceptions, missed blocking assignments on offense, missed pass coverage on defense.

The other three men in the room were Billy Willingham, Elmer Redd, and Larry Zierlein. Willingham, 58, who coached the offensive line, had worked for Yeoman for twenty years. He studied the films with a soggy cigar clenched between his teeth. He had not lit a cigar since he quit smoking ten years earlier; now he merely ate them. Elmer Redd, wearing boots, a ten-gallon hat, and a massive belt buckle, had signed on with Yeoman in 1970 after a spectacularly successful high school record in Lufkin. Now responsible for the offensive backs, Redd was the first black football coach at a major Southern university. Zierlein, a forty-year-old Viet Nam Marine veteran, assisted Willingham and Redd.

Having studied the films, the four men puzzled over how to outsmart the hefty Aggie defense. They talked for hours, but the discussion would have little impact; Yeoman is a coach who believes in sticking with a system—game after game, year after year. That system is the veer, of which Yeoman is the father. Born in 1964, the veer offense gives the quarterback three options as the play unfolds: to hand the ball off to a running back headed through the middle; to fake to the back and take off around end; to carry the ball himself or pitch it to a second back trailing behind him. Yeoman has stayed with the veer for twenty years, even while other teams moved to more pass-oriented offenses. College strategy has come full circle; many teams have gone back to option offenses, and several—including TCU and Tulsa—run Yeoman’s veer.

In midafternoon Yeoman headed for the locker room to change into his practice uniform. It was red and white UH issue from gimme cap to Nike sneakers. A silver whistle hung on a string around his neck. The coach was ready for the team’s workout, but it was not yet time to head out to the practice fields. He sprawled out on the black sofa in his office for a daily ritual: an afternoon nap. At four-fifteen, after twenty minutes, Yeoman’s secretary, a pretty UH coed, knocked on the office door to awaken him. The coach emerged, looking recharged.

Practice was held on three grass football fields, where the downtown skyline was visible over a line of trees. When Yeoman walked out, the team was loosening up—sleek receivers gliding across the grass; linemen puffing along behind, their bellies jiggling out over their padded pants. The team split up, defense to the playing field on the left, offense to the one on the right. An observation tower offered a crow’s-eye view of the proceedings, but Yeoman wasn’t interested in looking down on his players. Instead, he stood in the middle of the empty field in the center with his arms folded, staring intently at one group’s practice, then spinning 180 degrees and checking out the other. Every few minutes he leaned over to spit in the grass.

Yeoman was looking for clues to how his team would perform on Saturday. The game against A&M was critical. A loss would leave UH 1–4, well on its way to a disastrous season. A victory could turn things around. Yeoman knew from the films that this A&M team, 3–1 already, was good, perhaps the toughest Aggie squad he had ever taken on. Moreover, UH had beaten A&M only once in eleven tries at College Station.

A golf cart pulled up to Yeoman. Its driver was team trainer Tom Wilson, who had been at UH for 33 years. Wilson was distinguished by his taciturn manner and his artificial leg—he had lost the limb at age fifteen in a football accident. Wilson updated Yeoman on the status of Chip Browndyke; the team’s placekicker had broken his arm making a tackle against Baylor and had undergone surgery Monday morning. Could he play? Wilson was unsure. “He’s one of those that’s got to play,” said Yeoman grimly. “For crying out loud, he doesn’t kick with his arm.”

Shouts from assistant coaches directed the drills. Players grunted as they threw their bodies into one another and cursed as passes fell to the ground beyond their reach. Yeoman took it all in, this symphony of football, humming softly to himself. In previous years he had blasted his practices with amplified Aggie fight songs to prepare his team for the deafening hullabaloo sent forth by the Aggie partisans. This year he discontinued the practice. I asked him if the conditioning had been a failure. No, said Yeoman. “I just can’t stand listening to it anymore.”

A sportswriter walked up to Yeoman at midfield, and the coach suddenly shifted into cruise control. He had heard all the questions thousands of times before and had given all the answers.

You think your guys can turn it around?

“Nothing is done in an instant,” said Yeoman. “You usually have to pay a price.”

Your backup quarterback didn’t look bad.

“Coach, he’s a football player.”

A couple of students practiced golf swings in the distance. A few girls jogged circles around the field.

How’s Eddie doing?

Yeoman shook his head. Eddie Gilmore, the team’s starting nose guard, had reported to fall practice at 320 pounds—40 over his ideal playing weight. He was still well over 300. “He’s a big fat toad,” said Yeoman. “He’s just starting to get in shape—halfway.”

Yeoman blamed Gilmore’s girlfriend for his nose guard’s girth. She had worked during the summer at a fried-chicken restaurant, said Yeoman, and had brought Eddie a bucket every night. Yeoman shook his head again at the wasted potential. “If Eddie had been two-eighty, he’d have been an All-American.”

After wind sprints the varsity regulars clustered around Yeoman in a knot of red and white. The coach spoke briefly, then everyone clasped his neighbor, sank to a knee, and bowed his head in prayer. “Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. . . .”

The regulars ran off, leaving behind the bottom of the team’s roster—the freshmen and the backups who had seen no action in the game against Baylor. This was a different lot; they were smaller and younger and less sure of themselves. They were there to participate in the regular Monday scrimmage for those aspiring to greater things; it was their chance to impress the coaches. Yeoman’s staff called it the Opportunity Bowl.

As the scrimmage began, one player lay on his back on the sidelines, holding his arm, his face twisted in pain. “He’s dislocated his shoulder,” an assistant trainer told Tom Wilson as he drove up in his golf cart.

“Lay down flat on your back and I’ll fix that real fast,” said Wilson. “Ever done this before?” Twice, said the player. Following Wilson’s directions, the assistant trainer lodged his heel in the player’s armpit for leverage, then pulled slowly, ever harder on the player’s arm. Harder, said Wilson. The player grimaced. Finally, the shoulder popped back into place.

“Three more sets,” Yeoman called to the rookies. The sun was sinking over the treetops. It was close to seven. A kid-faced freshman quarterback from Dallas fumbled a second time. “Damn!” muttered Yeoman. Finally, the quarterback got a handoff away cleanly. “That’s a good job,” Yeoman shouted.

Wilson told Yeoman about the dislocated shoulder. “Damn!” said the coach. “Tell him to let it rest.” Yeoman walked off the field with Redd. “They’re good kids,” the head coach said. “You just got to remain calm.”

Tuesday

Bill Yeoman summoned a secretary into his office. He had arrived at six that morning to study films, and now, five hours later, he was going through his mail. He handed the young woman a pair of envelopes. “Give these to T.J. and Carl when none of the other guys are around.” Yeoman’s two best players—defensive tackle T. J. Turner and tight end Carl Hilton—were being invited to the Hula Bowl, and the head coach did not want to make a fuss over it. Too many of his players already entertained unrealistic dreams about a career in pro football. Yeoman deplores the mystic influence professional football has on his college players. “I’m talking to kids who read that Tony Dorsett has frittered away millions of dollars and that his team then makes sure it doesn’t matter to him. You go talk to a nineteen-year-old kid who sees this and explain to him that if he doesn’t do something, he’s going down the tubes, and he dies laughing.”

Getting football players through college remains a struggle. To keep scholarship athletes eligible, UH spends more than $100,000 a year on a program begun when track superstar Carl Lewis flunked out. Lee McElroy, a former UCLA linebacker, high school coach, and principal, presides over a seven-member academic support staff with offices across the hall from Yeoman’s. Despite the program, few football players graduate with their class. McElroy expects only six of the seniors on this year’s team to do so. The problem is the athletes’ unrealistic on-field aspirations and nonexistent off-field ones. “Anywhere from sixty to seventy per cent of our football players think they’ll make it in the pros,” says McElroy. “Many are coming in here thinking they’re going to be Eric Dickerson.”

After his weekly luncheon with football writers, Yeoman headed to the Cullen Frost Bank downtown. He drove down Scott Street, then through Houston’s Little Viet Nam, home of Asian refugees. “They really have taken advantage of the great American dream,” he said, looking at the world outside. “Everybody in America sits on their keister and whines. That’s why these kids are important. They’ve gotta be worked with.”

Working with young athletes—particularly young black athletes from backgrounds totally unlike his own—has allowed Yeoman to make his mark. Until Yeoman arrived at UH in 1962, the team’s history was strictly small potatoes; its only postseason appearance in sixteen years had been in 1951, when the Cougars beat Dayton in the Salad Bowl. In his first year Yeoman took the team to the Tangerine Bowl (there have been ten bowl appearances since). In his second year he made the most fateful decision of all: he decided to recruit Warren McVea.

McVea was a star running back at San Antonio’s Brackenridge High School. He would have been at the top of the recruiting list of every major Texas university, had it not been for one thing: McVea was black. No Southern school would have McVea; national powers like Ole Miss, Georgia, and Tennessee had no interest in a black player. For Yeoman, McVea was perfect. Yeoman had recruited blacks as an assistant coach at Michigan State, and he saw no reason why he should not do so in Texas. He was just waiting for the right athlete. “He had to be as good as there was in the world,” says Yeoman. “The first one had to be a success.”

When McVea, during a game against Ole Miss in 1967, became the first black to play football in Oxford, Mississippi, Yeoman and several players received death threats. “I found out years later that our kids got calls in their hotel rooms. They were told if they scored, they’d be shot. We broke Warren on two trap plays where he could’ve scored running backward. Somehow he didn’t make it into the end zone. I was incredulous.” Houston lost, 14–13.

For years Yeoman recruited black athletes in ghetto neighborhoods and in back-roads Texas towns where other big-time coaches refused to go. Talent was the raison d’être of Yeoman’s actions; he was no liberal crusader. “I told the black leaders, ‘I’ll let you know I’m prejudiced. I’m prejudiced against bad football players.’ I recruited football players—who happened to be black. It was no issue to me.”

UH football teams were barred from competing for the Southwest Conference title until 1976, after eight rankings among the nation’s top twenty in Yeoman’s first thirteen years. Even now, Yeoman retains a bitterness about the lack of respect his school receives from its bigger, more powerful rivals. UH has academic departments and athletic programs equal to any in Texas, yet it is still treated like a mutt. The residue of racism is one inescapable explanation, reinforced late last year by a Cotton Bowl official’s widely quoted lament that UH would be in the contest: “Dammit, half of those people from Houston will come up here and eat at 7-Eleven stores, and the other half will be trying to hold them up.”

Back in Yeoman’s office, the coach talked about recruiting violations, which are rampant in the Southwest Conference. SMU has been placed under severe NCAA sanctions. TCU has suspended seven football players for receiving illegal payments. The NCAA is investigating whether a Texas A&M booster provided quarterback Kevin Murray with a sports car and cash. But amid college football’s darkest storm about illegal recruiting, there are no clouds over Houston and Bill Yeoman.

Houston’s football program has been on probation twice during Yeoman’s 24 seasons—most recently in 1977 for arranging an improper car loan for a recruiting prospect. Yeoman has a widespread reputation for refusing to buy players, but he will not talk about apparent violations by other schools. “If there was one human being down here without sin, then he could go ahead and point the finger,” said Yeoman. “There’s no one that doesn’t break a rule sometime. That’s why anybody who reports anybody is an idiot. Anybody who professes to be purely squeaky clean is not.”

Yeoman also keeps quiet because he is a firm believer in minding his own business. This is not a man who searches for battles. “We’ve made more inroads in twenty-four years by being gentle than we would have made in six hundred years by fighting,” he said. “As long as we keep our mouths shut and paddle our own canoe, we’ll be okay.”

Wednesday

After spending the morning with a film projector, Bill Yeoman turned to assistant Billy Willingham to offer his analysis of the Aggie field strategy. “What they’re trying to do,” he said, “is take those great big people and hammer your butt up there.” Willingham nodded.

“Billy, how’s your toe?” Yeoman asked Willingham. “It’s okay,” said the assistant coach, chomping on a cigar. “I had three ingrown toenails cut out a month ago. Those toes get stomped on and they turn all kinds of colors.”

Wednesday is the slow day in Yeoman’s weekly schedule, but there is no day of rest during the fourteen-week season. On Sundays he goes to church at nine o’clock, but leaves before the closing hymn to make it to his weekly television program, The Bill Yeoman Show. He meets his family for brunch at the Houston Club, then drives to campus to watch films and oversee a brief team workout at five.

Yeoman is paid $100,000 a year and receives a country club membership, free use of a new car, and extra money for the TV show. He occasionally has time for his favorite pastime, a round of golf, though he never plays during the season; he worries that someone might see him and complain that he is not paying attention to his job. Alma Jean, “A.J.,” Yeoman’s wife of 35 years, drags him to the opera on occasion, but he is not appreciative. “I died laughing the last time she took me,” he said. “It was a couple of homos. She didn’t even know what was going on. I said, that’s the last time I’m going to that crap. I can get that action without paying for it.”

The Yeomans take two weeks of vacation with several other coaches and their wives in May or June. A.J. would attend the game against A&M, but she would not travel to College Station with the team. The one time Yeoman had allowed wives to stay with the coaches before a road game, UH lost, 34–0, to Arkansas. No more. “It adds a degree of festivity,” said Yeoman solemnly. “This is not a festive occasion. It’s serious business.”

Yeoman glanced at the newspaper sports pages on the table in the projection room but didn’t pick them up; he does not read them during the season. Yeoman considers too much knowledge a dangerous thing. He believes his wards suffer from living in the media age. “When I was growing up, there was no communication at all,” said Yeoman. “I can’t think of a greater way to live: not to have available to me all the problems of the world. Since there was no television, I used to sit on a corral fence and watch the sun go down. I got exposed to love and responsibility very gently. I bet there are about ten million kids that would love to just sit on a corral fence and watch the sun go down.”

The coach offers no apologies for his sport’s obsession with victory. Says Yeoman, “When God’s wrestling for the soul of a man, winning’s important to him.”

Yeoman drove to the athletic dorm for lunch and parked in front of the No Parking sign. “Mama, how’re you doing?” he asked a woman dishing up vegetables inside.

“Mama’s fine,” she said. “You keep Mama smiling.”

“Well, I’ll tell you,” said Yeoman, “I’m going to be a lot funnier when we start flipping some people’s backsides.”

Practice began as usual at four-thirty. Yeoman seemed less pleased this day. He yelled frequently at his players for missed assignments and signs of laziness. “Hurry back, dammit! I’m tired of that walking around. . . . Hit that linebacker. . . . Get your butt around.” And at the session’s end there was no praise. “I don’t know what’s going through your heads,” he said sternly. “I wish I could open them up and look in. I tell you, if you want to win, it’s going to take the same physical effort, but a whole lot more effort mentally.” The team prayed and left for the lockers. I asked Yeoman why he was unhappy with practice. “I wasn’t unhappy,” said the coach. “You just gotta snarl at ’em every once in a while.”

Thursday

“We’re a long way at the University of Houston from being the strongest, in terms of power and prestige. But as long as He’s running it, it’s going to be dandy.” It was 6:45 a.m. and Bill Yeoman was sharing pancakes and wisdom with sixteen well-scrubbed teenagers. The occasion was the Youth Breakfast Club meeting at his church, St. Luke’s United Methodist, where Yeoman sits on the board. “It’s a little better deal if you let Him run things. I don’t see how people get along without it. Hey, I get along there sometimes, and we’ll blow a conversion or miss a touchdown, and I’ll wander sometimes, but not for long.”

His talk over, Yeoman joined hands with the girls on either side of him as the group bowed heads in prayer. Then Yeoman left for his next meeting, a nine o’clock session of the board of Long Point National Bank. “An old Cougar used to be the president,” he explained.

Noon brought another regular appointment: the meeting of the Taxi Squad, UH’s booster club, at the Marriott Astrodome. The luncheon turnout was healthy despite the team’s 1–3 record; all thirteen tables were filled. Yeoman spoke briefly about the strength of the conference and the team’s noble effort. The questions were relatively gentle; this was a friendly crowd, the Cougars had a tradition of starting slowly, and it was still early in the season. Yeoman ducked out to return to his office.

The coach keeps Thursday workouts light, with little blocking and tackling, to let the players conserve their strength for Saturday. For 45 minutes they walked through drills. It was a hot, muggy day and the team looked as sluggish as the weather. Now Yeoman was genuinely angry; the jokes stopped, and his lip curled. “Losing is a stinking, lousy, contemptible habit,” he lectured the team after practice. “But you want to know something? It’s the easiest way to go. We’re capable of winning—if we play out of our skulls.” He paused and took measure of his men. “You better get deadly serious. You better start to get your mind tough. Because an irresolute mind is going to get you killed on Saturday! Get down!” The prayer did not cool his temper, as he watched his players stroll off the field. “Why don’t you sprint off the damn field instead of walk?” Yeoman hollered. “Maybe it’ll give you a little intensity. Run, dammit!” The players scattered.

Friday

There is a brief time-out during the football season on Friday mornings, the calm before the storm, when Bill Yeoman and A.J. have breakfast. On this Friday they were eating at the Sugar Creek Country Club, just down the street from their home.

“I didn’t really want to come here,” said A.J., an attractive woman with a streak of silver in her dark hair. “I was having a wonderful time at Michigan State as an assistant coach’s wife.” But Yeoman’s wife didn’t really have much choice. Her husband had been a young assistant coach for eight years, and young assistant coaches want to become old head coaches. At 34, Yeoman accepted the position at the University of Houston, a little-known school for commuters and military veterans, and his wife had dutifully followed. “I cried all the way to Indianapolis,” said A.J. “Bill pulled off the road, and said, ‘That’s far enough.’ ”

After breakfast the Yeomans adjourned to their home, a residence turned upside down for football. When they built the two-story structure twelve years ago, the Yeomans placed their entire living quarters, even the kitchen, on the second floor. The first floor is public space, large open rooms built for entertaining. It is dominated by the Cougar Room, a nightmare of football memorabilia, including a red and white UH lamp, a red and white rug, a red and white telephone. Even UH-colored candy: peppermints. On top of the television sits a small lettered sign: “We interrupt this marriage to bring you the football season.”

The football season is Alma Jean’s busiest time too. The Yeomans entertain regularly, and the assistant coaches and their families come over after most games. “You have a responsibility to the faculty and your husband and the boosters, even the ones who don’t like you and are trying to have your husband fired,” she said, a stain of bitterness in her voice. “People like that don’t know what he’s given up for them, for their school, not his school. I’ve watched them butcher him. Let me tell you, it’s not fun.” She paused and contemplated their peculiar lot. “Sometimes in the middle of a game I think, ‘You know, our livelihood depends on eighteen- and nineteen-year-old kids.’ ”

Yeoman comes home after games and lies awake until two or three in the morning. I asked his wife how he deals with the pressure. She smiled. “Chocolate sundaes with lots of nuts.”

Shortly before three, the football team began boarding two chartered buses parked outside the athletic dorm. The first-team players would ride on the first bus, which has 26 extra-large seats. The team would spend the night at the Holiday Inn in Huntsville, midway between Houston and College Station. Yeoman stood outside the two buses, a grim look on his face. There was no joking here. This was serious business.

“Time to go to war!” said a player as he hopped on the front bus. Yeoman nodded. At precisely 3 p.m. the football caravan pulled out behind a police motorcycle escort. At the hotel Yeoman ordered all incoming calls to the players’ rooms to be blocked. There were to be no distractions. The offensive players were placed together in one group of rooms, the defensive players in another.

At six the team ate quietly in the hotel’s Houston Room—steak, baked potatoes, salad, green beans, and iced tea. Dessert was a dish of cake, peaches, and ice cream. A player signaled a waitress to deliver a second helping. “Hon, I’ll tell you, just give them one,” said Yeoman. “It’s going to be hot tomorrow, and if they have very much on their stomachs, they’re going to throw it up.” The weather prompted another change in routine. Yeoman traditionally held a team meeting at ten with hot chocolate and cookies. He ordered the cookies dropped from the menu.

Yeoman had been captain of his Army team, where he played and later served as assistant coach under the fabled Red Blaik. “I used to laugh at Coach Blaik and his great motivating speeches,” he recalled, sipping coffee after dinner. “We’d all be lying around on the floor. He’d walk in and say, ‘Well, let’s go kick the crap out of them,’ and then he’d walk out. That was it. Every week. Every year.”

At ten the players began arriving for the final team meeting. One looked around for the sweets. “No cookies tonight,” said Yeoman.

“Coach, you’re going to feed us salt water next week,” the player complained.

“I tell you, when that sun comes out tomorrow, you’ll be glad. The last time we had cookies before an afternoon game you barfed them up. I had to walk through the cookie mess. Besides, you’re too tough for cookies.

“I don’t want any television sets on when you go back to your rooms,” Yeoman lectured the team. “You’re going to have a chance to win this football game tomorrow if you think right. You’re going to have to spend some time looking at the ceiling and thinking. The physical effort—there’s nothing wrong with that. You guys are busting your fannies. But you guys have to get your heads right. This stuff of playing close and not winning is a disease—and it’s the worst disease in the world. Let’s just get ourselves ready to beat a good football team. The only way we’re going to do that is to get your heads right. Okay, let’s play.”

Fifty miles away, as the Houston Cougars slept, the far stands of Kyle Field at Texas A&M were filled with eight thousand Aggies conducting Midnight Yell. For an hour they remained, singing and chanting and listening to a vulgar apocryphal tale about a game of “fag football” between UT and Houston. “Who’re we going to beat?” screamed the yell leader. “Cougar High!” shouted the crowd.

Saturday

“Slot left jet 354 R out.”

“411 flat quick R post.”

It was 4:50 a.m. and Bill Yeoman was sitting up in his bed at the Huntsville Holiday Inn, practicing calling plays. He cannot sleep more than a few hours before games, so he uses the predawn hours to get in a bit of practice of his own.

His players arose three hours later, greeted with glasses of orange juice delivered to their rooms. By then Yeoman was up, wandering the parking lot of the hotel and looking up at the thick skies. “Hot and muggy,” he said, shaking his head.

Elmer Redd appeared, fresh from a scouting trip to Tyler to watch a high school quarterback. “How’s the kid?” Yeoman asked him.

“Terrific. He can flip the ball. He did everything but turn the lights off. And he’s an honors student.”

Yeoman mulled over the prospect. “It’d be nice to have an honors student.” Houston’s starting quarterback, junior Gerald Landry, strolled by on his way to the hotel bar, where the players were getting their legs taped for the game. Yeoman gave him a bear hug. “How’s your wheel?”

“Pretty good.”

“Listen, they’re going to try and make you run, so we’ll run some four and six dives to try to hunker ’em down.” Landry nodded, and Yeoman slapped him on the back.

At ten the players arrived for the traditional pregame meal of steak, pancakes, and iced tea. Two electrolyte tablets, to combat heat cramps, sat on top of the coffee mug at each place setting. As the food disappeared, Yeoman stood up near the front of the room. “There’s absolutely nothing that beating A and M won’t cure,” he told the players. “If you thought you got badgered by the Baylor Baptists, I tell you, you’re going to get badgered like you can’t believe today. I don’t want any nonsense from anybody. There isn’t any way you should play if you can’t do it with some class.”

In the dining room after the meal, Yeoman introduced a minister from Houston for the team’s pregame chapel service. “In football you need a playbook to know what to do,” the minister said. “Well, God has a playbook also, and his playbook is the Holy Scriptures.”

The team adjourned outside. The sun was beating down now; it was going to be an astonishingly hot day for October. Yeoman led his team on its pregame walk, intended to get circulation flowing. It was a strange sight: the 57-year-old white-haired man leading sixty strapping, neatly dressed youths through the streets of a residential neighborhood behind the hotel. Three blocks out, three blocks back. Afterward, the offensive squad met in the back parking lot to walk through plays. It was the final check to make sure everyone knew his assignment. Yeoman shouted plays, and his team went through them in slow motion. After twenty minutes the team was ready to board the bus.

A motorcycle escort took them the fifty miles into College Station. The rear bus grew quiet as it entered College Station. There was a pervasive feeling of entering enemy territory. At twelve-thirty—ninety minutes to kickoff—the buses pulled up beside Kyle Field, past tailgaters and flat-topped Corps members on horseback, participants in the halftime show. “Let’s shoot the horse!” called a UH player. “Faggies!” “Eh!” called the bus driver as he opened the door. “Kick their asses!”

The team dressed quickly—Browndyke, with his broken arm, needed help with pulling up his pants—then headed onto the field for warm-ups. Yeoman walked onto the AstroTurf to survey the scene. The stadium was filling rapidly; 55,105 would be in attendance, short of a full house but twice the average UH home crowd. The sun was brutal; the field temperature was nearing one hundred degrees.

Yeoman ducked back into the locker room and changed into his game uniform, then headed out to midfield to chat with Aggie head coach Jackie Sherrill. Here was a clash between the old breed and the new. Yeoman wore red slacks, UH cap and shirt, red and white sneakers. Sherrill, fifteen years younger, and dressed in a long-sleeved white shirt, narrow tie, gray pants, and black shoes, looked more like a banker than a coach.

Already the noise was astonishing; the huge Aggie band sat directly behind the UH bench, blaring away. The Cougars ran drills and exercises for 45 minutes before Yeoman shouted them into the locker room. The dank room was thick with the smell of sweat and the edge of nerves. “Gotta have this one!” players shouted.

“Gotta!” echoed Yeoman. “I tell you,” said the coach. “We’ve got to ram that ball down their throats. You people on pass protection bust your fannies! It’s going to be hot. I don’t care. You’ve got to bust your fannies.”

“Gut check babe!” called a player.

“One play at a time, you understand? Don’t get sloppy in the head.” Yeoman paced back and forth, as the players listened from benches or the cement floor. “Gotta play hard, gang, harder than we’ve done before, because what we’ve done before hasn’t been enough. Pay attention, by golly, to just how much this thing means.”

“Have to play!” echoed the players.

“Here we go!” said Yeoman.

“Those Aggies get me fired up!” said split end Kevin Johnson, quivering with excitement in the back of the locker room. “Here we go! Here we go!”

“Kevin, come down here,” Yeoman told the receiver. “I love you like a son. You’ll get your chance.” Yeoman looked around at his players.

“All right, get in here. Tight together. Our Father . . .”

“I’ll tell you what,” Yeoman said. “The only friends you got out there are the guys standing next to you. I tell you what. Every one of you guys have gotta grow up. We’re all in this together, gang. Everybody’s got a part to play and everybody’s got to play it absolutely out of his skull. All right. Let’s go!”

The game began as well as it could. Houston took the kickoff and moved the ball with machinelike efficiency downfield for a score: twelve plays, 62 yards. UH 7, Aggies 0. Chip Browndyke, his arm in a cast, kicked the ball into the end zone. On his third offensive play Aggie quarterback Kevin Murray lateraled the ball toward one of his backs; the pitch was missed and then batted into the end zone for a safety. Suddenly Houston had a stunning 9–0 lead and the ball to boot.

This was a chance to take charge, to move sixteen points ahead and prove the first score more than an opening-quarter fluke. Landry began moving the ball downfield again, 28 yards, to the A&M 25. The players were up off the bench in excitement. Everything was going according to plan. They could turn it all around, maybe even go to the Cotton Bowl again. Anything was possible. The quarterback gave the football to back Michael Simmons, who broke free toward the end zone and . . . lost his grip on the ball. A&M recovered. “Don’t worry about it, Mike,” the players told Simmons as he came off the field.

But the balloon had burst. Yeoman’s offense went into a deep freeze. Runs through the middle went nowhere; Landry’s passes went astray. In the next six possessions the Cougars managed only one first down. A&M, meanwhile, began grinding out yardage. By halftime the Aggies had scored two touchdowns and a field goal. Houston was trailing 17–9.

The enemy crowd hissed as the Cougars walked down the sideline for the locker room. “Give it up, Bill!” an Aggie heckled Yeoman. The coach spent the intermission grilling his players about the Aggie defense, trying to figure out why nothing was working. Why had a block been missed? “Crap, son, you know the starting count,” he told a lineman. “Get your head in there and stop him!” The referee stopped in the locker room to say the break was up. “Gotta go to work, guys!” Yeoman hollered. “Dadgummit and the heck, let’s get out there and play some football!”

The team rushed onto the field, but the second half was even worse. The offense went nowhere on its first two possessions. The third produced an interception that was returned for a touchdown. Landry fumbled on the fourth and was tackled for a safety on the fifth. A&M scored nineteen unanswered points, and it was 36–9.

“What the hell’s going on?” Yeoman demanded of a lineman. With eight minutes left in the game, Yeoman pulled Gerald Landry. The coach put his arm around him. “Gerald, you’re fine. You’re just not getting much help.” With the score 43–9 and time running out, Landry’s replacement, Mark Davis, began to move the team downfield. Aggie fans screamed as though the game hung in the balance. Yeoman wanted the score, and most of his starters were on the bench. “Carl Hilton, get in there,” he called to the All-American tight end. Yeoman called a run off tackle at the one-yard line. His freshman running back slid into the end zone. “Want to go for two?” Yeoman asked Redd in excitement. The game ended 46 seconds of playing time later. Texas A&M 43, Houston 16.

Bill Yeoman, looking exhausted, spoke quietly to his players in the locker room. “I’ll tell you what, gang, we’re going to go back Sunday and play like this didn’t happen. We just disintegrated. You’re a heckuva lot better football team than that nonsense out there.” Yeoman shook his head. “We need to worry about SMU. Just get on the bus, worry about them, and we’ll start again five o’clock Sunday.”

“Hang together!” an assistant coach called. The players and coaches fell to one knee, bowed their heads, and prayed.

Yeoman retreated to the coach’s dressing room and stripped off his red pants. A crowd of reporters and television cameras followed him in, asking what had happened, while the coach sat on a folding chair in his underwear. “Game like that, you can’t get all lathered up,” Yeoman told the press. “You’ve just got to remain very calm and prepare for SMU.” The reporters asked a few more questions, then stood around awkwardly in silence before excusing themselves. “Thanks, Bill, we appreciate it.” Yeoman stripped off the rest of his clothes and stared into the ground. A SWC radio broadcaster suddenly explained that he was live and handed the coach a headset. Buck naked except for the device around his head, Yeoman patiently answered questions for three or four minutes. Excused at last, he walked off to the shower.

Yeoman dressed quickly and headed for the team bus. “Gotta go back to work,” he said as he stepped into the daylight. “Time to start over.”

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- College Football

- Aggies

- Houston

- College Station