ASHLEY SWANSON WAS NOT THE kind of girl you would expect to find in a beauty pageant. At sixteen, she stood six feet two inches tall, and she walked with the awkward gait that very tall girls do, when their bodies seem to be all elbows and shoulder blades and long, skinny legs that have not yet found their center of gravity. She rarely wore makeup, and her chestnut-brown hair was often pulled back, perfunctorily, into a ponytail; when it hung loose around her shoulders, it got on her nerves. Until recently, her only concession to glamour had been her eyebrows, which she tweezed into half-moons that arched above the brown frames of her glasses. That was until one weekend last fall, when she became contestant number 53 in the Miss Texas Teen USA 2003 pageant. For three days, she was Miss Gray County.

Exactly what motivated Ashley to take part in a beauty pageant involved reasons less obvious than a desire to win. She had learned of the pageant last summer, when a postcard came in the mail along with a handful of teen-magazine subscription offers and cosmetics ads. The postcard featured photos of five beauty queens beaming beneath their crowns. “the chance of a lifetime,” it announced. “you could be next!!!” Farther down, it read, “Miss Texas Teen USA in November! . . . As a contestant, you will be judged in three equal categories, consisting of personal interview, swimsuit/fitness, and evening gown. There is no performing talent category . . . To become a contestant in this year’s event, complete this form . . . Apply today!” Anyone who wanted to become a contestant was asked to send her name, address, and a recent snapshot (no beauty queen title was required, only an entry fee) to the pageant headquarters, in Houston, which Ashley did. When I asked her why she had decided to enter the competition, she shrugged as if she were still trying to make sense of it herself. “Curiosity?” she said. “I don’t know. I think I’m trying to figure out how to be a girl.”

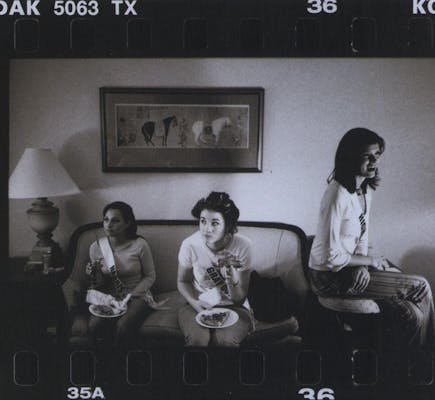

The day after Thanksgiving, four hours before the Miss Texas Teen USA 2003 pageant orientation was set to begin, Ashley sat in a Houston hotel lobby, waiting. She wore a white peasant shirt, blue jeans, sneakers, and a worried expression. Her excitement had given way to a bad case of nerves, and she fiddled with her silver pendant necklace as she talked. “I just keep thinking,” she said, “‘What have I gotten myself into?'” At dawn the day before, she and her family—her mother, stepfather, little sister, and two dogs—had left Pampa, the Panhandle town where they lived, and the 619-mile, eleven-hour drive had provided her with ample time to second-guess herself. Her mother, Crystal, studied her with a mix of amusement and maternal concern, leaning over to brush a strand of hair from her face as we talked. Ashley was notoriously klutzy, her mother told me, and it was unusual for a day to go by that she didn’t stub her toe or run into a wall or fall down. “Just remember, honey,” her mother instructed her, squeezing her hand. “Stand up straight, look at the judges, and whatever you do, don’t trip.”

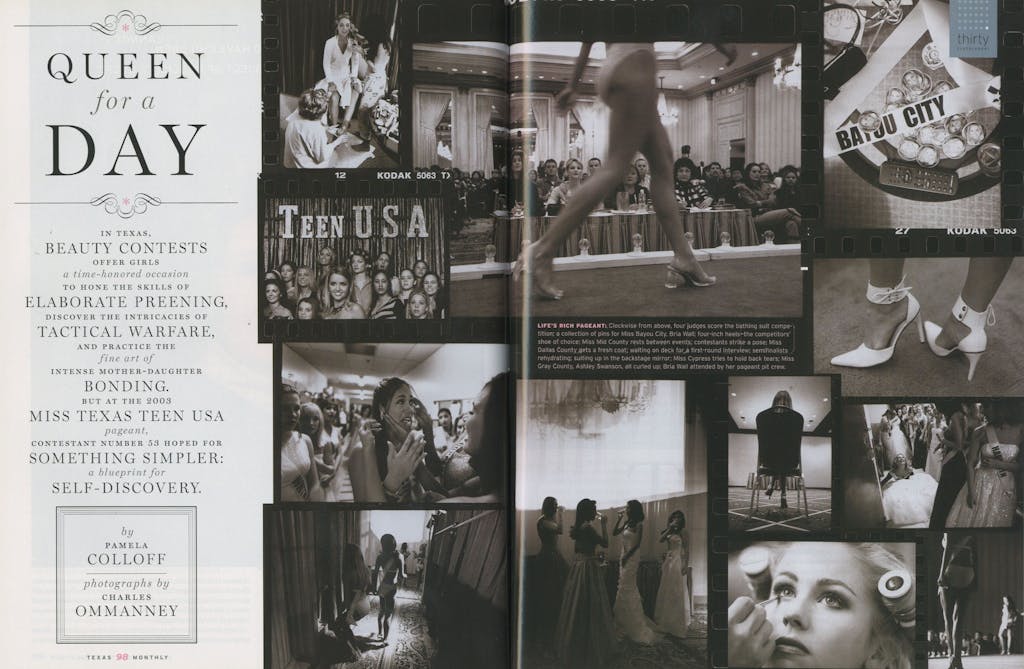

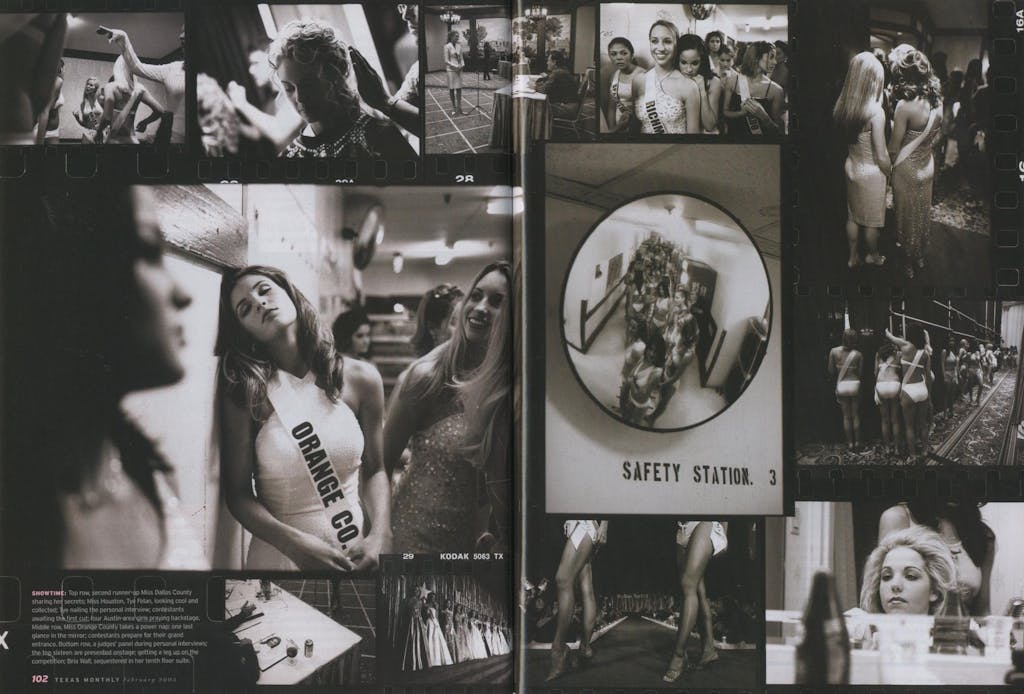

THE CONTESTANTS BEGAN DRIFTING INTO the hotel at noon. Outside the Doubletree Post Oak, near the Galleria, where the three-day pageant would take place, teenage girls stood fixing their makeup one last time as their mothers looked on, their arms draped with gowns made of candy-pink taffeta and ice-blue satin and ivory tulle. Bellhops maneuvered past them, wheeling carts stacked high with shoe boxes and matching mother-daughter luggage sets. Inside the hotel, the pageant contestants—who ranged in age from fourteen to eighteen—strode across the lobby, coolly appraising the competition. Miss Dallas County, a leggy blonde, made her entrance in a buttery brown-leather miniskirt, matching boots, and a snug, rhinestone-studded suede jacket lined with white fur. Among the other girls’ “arrival outfits” there was a crimson-colored knee-length coat made of alligator skin. A white silk suit adorned with sequined appliqué. A fringed buckskin ensemble. An off-the-shoulder black sheath dress. A leopard-print pantsuit. The veteran pageant girls all had tan Louis Vuitton handbags and French-manicured nails. Many of the first-time contestants—who had done no more than apply a fresh coat of lipstick before their arrival—looked on, bewildered.

The competition began the moment a girl stepped out of her parents’ car. The nine judges would not arrive until that evening, and the first scored event would not take place until nine o’clock the next morning, but the jockeying for position was well under way. Arrival outfits were worn with the intent of scaring off the competition, as were the withering looks some girls gave to each other as they stood by the bank of elevators. “It’s all a mind game,” Miss Bayou City, sixteen-year-old Bria Wall, told me several weeks before the pageant began. “You want to intimidate the other girls. You have to walk through that lobby like you already know you’re the winner.”

A few contestants had an aura of celebrity, and Bria Wall was one of them. Her parents had spared no expense in preparing her for the contest, providing her with her own pageant pit crew, including her own coach and makeup artist, as well as a dazzling wardrobe culled from Houston’s best boutique shops. No detail had gone unnoticed, down to the pink “Go Bria!” pins that bore her picture worn by her supporters. A petite blond cheerleader from the Woodlands, Bria had an intensity of purpose about winning the Miss Texas Teen USA crown that was fearsome. She had already memorized the names and photographs of the contestants she anticipated being her rivals, and she stood in silent concentration that afternoon, scanning the lobby for their faces. Primary among them was eighteen-year-old Miss Houston, a lithe, luminous blonde named Tye Felan. She had narrowly won the Miss Houston Teen USA pageant that spring (Bria was the runner-up), and to hear other girls talk, Tye was the girl to beat. For starters, it was believed that whichever girl represented Houston always had an edge at the pageant; in the same way that Texas beauty queens have a certain mystique on the national stage—eight Texans have been crowned Miss USA—so Houston girls do back home. But it was more than that. Tye represented a long-held ideal of the Texas woman: tall, blond, impossibly thin. In the hotel lobby, Bria and the other girls watched Tye from across the expanse of white marble, stacking themselves up against the girl they were supposed to strive to be.

At two o’clock that afternoon, all 117 contestants reported to the orientation meeting. Ashley Swanson sat in the fourth row of the conference room, hands clasped, alone. She did not talk to the other girls; she sat attentively, taking in the scene. Only a handful of girls had entered this pageant with no prior experience, as Ashley had done (girls who did not already hold a title received one for the weekend from pageant organizers). Most had already competed in a hometown beauty pageant, of which there are hundreds across Texas every year—some run by chambers of commerce, along with local harvest festivals; others run by the nonprofit Miss America organization, in which girls compete for scholarship money; and still others run by the for-profit Miss Universe organization (co-owned by NBC and Donald Trump), in which girls pay to compete for prizes. These pageants require standards and expectations little different from those that girls in Texas are supposed to measure up to every day, yet some girls, like Miss April Sound, had chosen to compete in hundreds of contests. Why they ran again and again seemed to have little to do with winning prizes. For the entirety of the Miss Texas Teen USA 2003 pageant, not one girl—save for Bria—ever mentioned wanting the $3,200 college scholarship, the diamond necklace, the gold-crown ring, the custom-made evening gown, the year’s worth of hair and makeup appointments, the clothing allowance, the chance to compete for the national crown in August, or the nineteen other gifts that made up the winner’s prize package. In a state where beauty is paramount, the validation the crown brings is its own reward.

The pageant’s producer, Al Clark, a jovial man in his early sixties, rose to make a few introductory remarks. (In 1991 he and his wife, Gail, an elegant blonde who was Mrs. Texas 1979, wrested control of the organization away from Richard Guy and Rex Holt, the famed El Paso duo who produced five national winners in a row in the eighties amid rumors of pageant rigging. The Clarks restored order, and in 1995 one of their own protégés, Chelsi Smith, won the Miss USA title and then Miss Universe.) “One of you will be the next Miss Texas Teen USA,” Al began, looking out over the room. “Who will it be? You have one chance in one hundred seventeen, and that’s not much of a chance. So rule number one is, Have fun. Rule number two is, Don’t listen to the gossip. You have a dream, and that’s why you’re here. Don’t let any petty person take that away from you . . . . Rule number five, Don’t let the pressure ruin the real you. Personality and warmth are what win these things. Almost all of you are pretty”—to which there were some audible gasps from the mothers standing in the back of the room—”so it takes more than just being pretty to win. And now, let me give you the Creep Speech. There are going to be a lot of men around this hotel who know the prettiest girls in Texas are here. Don’t give out your room number or your telephone number, please.”

The contestants were handed their sashes and herded down to the ballroom, where they would spend the next five hours learning their dance moves for the pageant’s jazzy opening number. “Beauty queens must wear heels at all times!” barked their choreographer, Kent Gregory Parham, as a few girls straggled into rehearsal wearing sneakers. His task was to transform more than one hundred girls of varying dance ability, grace, and coordination into a well-oiled machine capable of performing in perfect rhythm before a one-thousand-person audience—a small miracle he had to work in less than two days. By eight o’clock that night, the girls were weary as he schooled them in how to stride down the catwalk. “Ladies, walk like you’re teens, with a bounce in your step,” he yelled over the thumping music. “You don’t have mortgages yet. Show it!”

ASHLEY SAT IN HER HOTEL room that night, rubbing her feet. She was talking on the phone to her mother. “It went okay, I guess,” Ashley said. “These girls are so intimidating. They’re really, really pretty. I felt really underdressed. They wore four-inch heels to rehearsal! Gosh, it was long. We practiced doing the whole pageant. I walked around, swinging my hips and smiling at a crowd that didn’t exist, and it was very weird. We did imaginary awards and I won Best Swimsuit, and I had to walk an extra lap and smile more. But I’m pretty sure I won’t win Best Swimsuit tomorrow!” She laughed and picked up the regulation bikini that each girl had received that evening from the Miss Texas Teen USA organization, holding it out in front of her as if it were a dead animal. She was less mortified by the slightness of the bikini than by its color, which was her least favorite. “Mom, guess what color my swimsuit is,” she said. “Pink!”

After Ashley wished her mother good-night, she slipped on her size 12 heels and teetered around the room in her pajamas, demonstrating the exaggerated swagger of a veteran pageant girl. Her Miss Gray County sash hung inelegantly from the lamp shade, where she had tossed it after the rehearsal. “These girls are so prim and proper!” she marveled, laughing as she sprawled out across the bed. All she could do in the face of such competition was throw up her hands and laugh. The girls who were among the pageant’s most serious contenders had spent as much as $5,000 on evening gowns with hand-beaded bodices and hoopskirts and trains. Ashley planned to wear a $75 formal from her hometown dress shop—a simple ivory sheath with spaghetti straps—that she had bought two years earlier for her Pampa High School Band banquet. The more experienced pageant girls had sculpted their bodies with the help of personal trainers, diuretics, and strict high-protein diets. They had bronzed themselves on tanning beds and used a self-tanner called Fake Bake. But Ashley had just been Ashley. She was proud to report that her legs had not seen the sun since the summer and that her favorite after-school snack was still an Allsup’s chimichanga and a Coke.

This is not to say that Ashley was unconcerned about how she would fare in the pageant. She had worked hard to get there. Her family was of modest means—her mother worked as a teacher’s aide, her stepfather as a nurse at the local prison—and so she had raised every cent of the $950 pageant entry fee herself. Fellow parishioners at the Zion Lutheran Church, in Pampa, had taken up a collection for her, and her mother’s sorority sisters had chipped in as well; the remainder was donated by two beauty shops, an RV park, a handful of mom-and-pop stores, and Pampa Pawn. Ashley had no local pageant director to guide her, and she could not afford a coach who would instruct her in the finer points of pageant finishing school. Unlike, say, Miss Houston, she had not been taught how to pivot in four-inch heels while smiling at the judges. She had not been drilled for hours on end in the art of answering questions like, If you could ask God one question, what would it be? She had not been taught the tricks of the trade, like how to use duct tape to push up her breasts or the importance of doing lunges before the swimsuit competition so that her calves would appear shapelier. Ashley did only what she knew how to do. “My strategy tomorrow is to be myself,” she said.

When her roommate, Miss Grayson County, returned to their room to sleep, I left them to join chaperone Donna Buchanan on her rounds for the eleven o’clock bed check. Mrs. Buchanan, as she was known to the girls, was the silver-haired grande dame of the pageant, whose twin daughters had both been beauty queens; she had watched one twin crown the other. At curfew, she began knocking on doors, giving stern warnings to stay put until the morning. “Girls, we’re not running a brothel here!” she chastised two contestants whom she spotted lounging in the lobby in their pajamas. With each door that opened, a different girl stood before Mrs. Buchanan, her face stripped of the day’s war paint. Here, in the bright hallway light, the girls appeared as they really were, with frizzy hair and splotchy complexions and crooked teeth in retainers. Girls who earlier that day had walked through the lobby with such womanly sophistication—even a studied sexuality—now stood, barefoot and yawning, wiping the sleep from their eyes, looking for all the world like children who had had a very, very long day.

THE PERSONAL INTERVIEW PORTION OF the pageant—in which the judges were charged with evaluating a girl’s “inner beauty, personality, and character,” as stated in their handbook—began at nine o’clock the next morning, without an audience, in a chilly hotel conference room. Each contestant had already filled out an official questionnaire, which provided the nine judges with information they could explore further during the interviews. The last question listed was “What makes you special or unique?” Ashley had written, “I can play flute, piccolo, piano, and bass guitar. The piano was self-taught.”

Other answers the judges received included: “I was switched at birth” (Miss Aransas), “My expensive smile” (Miss Austin), “I am a spirit-filled Christian and proud to live for Jesus Christ” (Miss Bexar County), “I have never had a cavity” (Miss Colleyville), “I love peanut butter on my pancakes” (Miss Cypress Creek), “Not too many people know it, but I am 25 percent Hispanic” (Miss El Paso), “I consider myself an amateur contortionist of sorts” (Miss Falls County), “I have really tiny feet” (Miss Harris County), “My sneeze” (Miss Paris), “I began community service at the age of three” (Miss South Plains), and “I am an eighteen-year-old virgin and I plan to practice abstinence until I’m married” (Miss Wood County). Under “Other Interesting Information,” Miss Wood County had continued: “I love canned spinach. I also have an interesting story about my teddy bear. Ask me.”

Outside the conference room, the contestants, who had the glossy appearance of television anchorwomen, waited their turn. Inside, they each stood stiffly before the judges, wearing pin-striped power suits and bright-red blazers, trying to make an impression in their allotted three minutes. Miss Permian Basin demonstrated how she could touch her nose with the tip of her tongue, and Miss Orange County showed off her skills as an auctioneer by pretending to sell the lectern she stood behind. (“Do I hear one dollar, one dollar, one dollar? Do I hear one-fifty?”) Other girls would have made their chambers of commerce proud. “I’m from Texarkana, and we say we’re twice as nice, because we straddle the state line!” gushed Miss Bowie County. Or they offered up colorful sayings: “My brother and I are so close that if he eats a watermelon, I spit out the seeds,” said Miss Tom Green County. The girls’ voices quavered, and some wore their uncertainty for all to see. “How did you prepare for this pageant?” a judge asked Miss Bayview. She sighed, then said, “I tried to find who I am, and I found it, I guess.”

Just before noon, Ashley stepped up to the lectern. She wore a flattering red dress, lipstick, and flats. She did not appear to be the same vibrant girl who had laughed the night before as the pageant unfolded around her; she looked as if she had lost her nerve. “I’m number fifty-three, my name is Ashley Swanson, and I’m Miss Gray County Teen USA,” she said with a wan smile.

“Hello, Ashley. Where’s Gray County?”

“The Panhandle.”

“So it’s cold?”

“Yes.”

“Where do you live in Gray County?”

“Pampa. It’s not very big, but it’s homey.”

“What would make us want to visit?”

“Um . . .” Ashley looked stumped.

“Is there a mall?”

“Yes, but there’s nothing in it.”

“How do you like the pageant?”

“It’s different. I don’t usually dress up.” Ashley searched for something positive to say. “I’m very shy, but it’s helping me to get up in front of people and talk.” She did not tell the judges that she planned to major in planetary geoscience when she went to college or that she loved the way the sun caught the rough edges of a rock when she held it in her hand. Instead, Ashley murmured a few more answers, and then her time was up.

Not far behind her was Miss Houston, Tye Felan, perfectly turned out in a champagne-colored silk suit, her hair falling in soft blond ringlets around her face. Tye was beautiful in a way that needed no adornment, with porcelain skin, blue eyes, a tiny waist, and a willowy dancer’s body. A devout Baptist, Tye could say things like “I think God put me on this earth to do the things I’m doing. I need to stay true to myself and to Him,” and when she said them, you believed her; she was without guile. Before the judges, she was a model beauty queen. She spoke about her lifelong dream of becoming a country singer like her idol, Faith Hill. She praised the many charms of Houston, and she spoke of her firm commitment to abstinence. “I’m very loyal and honest, and everything I do, I give one hundred ten percent,” Tye said, as the judges beamed back at her. “I’ve learned that anything is possible.”

Her rival, Bria Wall, made an equally lasting impression. While other girls had hung back, Bria walked up to each judge, extended her hand, and said, “Hello, I’m Bria Wall!” Rather than waiting to field a question once she returned to the lectern, she smiled and asked the judges, “How are you doing today?” Bria was two years younger than Tye and several inches shorter; while Tye was the elegant beauty, Bria was her cute kid sister. With a giddy enthusiasm, Bria described herself as a “daughter, friend, student, and community servant.” Of her future, she said, “I want to live my life so that when I look at myself in the mirror, I’ll know I haven’t done anything I’m ashamed of.” When she was asked what she would want if she could have one thing made of gold, she replied without hesitation, “The Miss Texas Teen USA necklace, to be honest!” Other girls had looked relieved when their three minutes had drawn to a close, but Bria seemed reluctant to go. When her time was up, she leaned forward and whispered, “It was great to meet y’all!”

THAT NIGHT, TWO HOURS BEFORE the “preliminary show and competition” was slated to begin, I spotted Ashley standing outside of rehearsal. She was in a jubilant mood. “Look!” she said. She had on mascara and black eyeliner—she was no longer wearing her glasses—and her hair was rolled up in a constellation of curlers. “So this girl in a pink-and-black shimmery suit grabs me after lunch and says, ŒYou’re coming with me,'” Ashley explained. “We’re walking really fast down the hall, and she says, ŒMy name is Alexis,’ and she says that three times. She’s Miss Coastal Bend. She said her makeup artist wanted to give me a makeover for free! I’m going up there so she can finish working on me. You can come watch, if you want.” We made our way to room 322, where a piece of paper was taped to the door that said, “Makeup room. Come on in.” Inside, under the high-wattage bulbs designed to reproduce the brilliance of stage lights, sat half a dozen teenage girls in robes, studying their reflections. Three women stood over them, applying powder to noses and blow-drying hair and spraying clouds of Aqua Net. One of the makeup artists was Nicole West, a short, stylish woman in her thirties who had never seen a face that could not be improved. When I later asked Nicole why she had decided to waive her fee for Ashley—the going rate was $300 per day or $600 for the entire pageant—Nicole described first seeing her at the dance rehearsal the previous afternoon. “I thought, ‘Why does this girl have her glasses on?'” Nicole said. ‘Why does she have her chin down?’ I looked at her and I thought, ‘I’ve been that girl before.’ We’ve all been that girl before. Ashley’s a beautiful girl; she just needed some help. I mean, she came here because of a postcard. When she told me that, I thought, ‘Man, you got guts.'”

Ashley sat next to a vast palate of cosmetics, and Nicole went to work. Her hair, which had hung flat before, was unfurled from the rollers and brushed out into lavish waves that framed her face. The contours of her cheekbones were accentuated with rouge so that her fine bone structure became more pronounced. Her lips were painted a russet color and lined to look fuller. Her eyes were fringed with false eyelashes. Her eyelids were dusted with rust and gold, which drew out the greenness of her eyes. All told, the transformation took close to an hour. When Ashley rose from the chair and assessed herself in the mirror, she held her shoulders back just a bit farther. Her face radiated a new vitality, as if she were suddenly in sharper focus. Everyone in the room gathered around her to look, creating a chorus of breathless compliments.

“You look awesome!”

“Holy crap!”

“I have goose bumps, Ashley. You’re a raving beauty.”

“Are your parents religious? They’re going to sue us!”

Ashley smiled, and then it was time to go.

“Keep smiling!” said Nicole, who looked as if she might cry.

Downstairs in the dressing room, the girls assembled for the preliminary competition. The judges would score them in swimsuit and evening gown that night; those numbers would be added to the personal interview score from earlier that day (each event counted for one third of the total score), and girls would be ranked accordingly. The top fifteen would be announced the next day, at the beginning of the final competition. Backstage at the preliminary, heads turned when Ashley walked into the dressing room, and a group of girls had soon gathered around her to exclaim over her appearance: “You look gorgeous, Ashley!” “Oh, my gosh!” “Wait, we need to take a picture together!” (“It’s interesting,” Ashley told me later. “Once I had makeup on, everybody wanted to be my new best friend.”) One girl jokingly accused her of having used her glasses as a ruse so that she could upstage the other girls at the last minute. The chaperones stood nearby, marveling. “Honey, you look magnificent,” said Mrs. Buchanan, pinching her arm.

A few hours later, each of the Miss Texas Teen USA contestants walked across the stage in two-piece bathing suits—girls who were thick-waisted, slim-hipped, flat-chested, long-limbed, jiggly where they were supposed to be, jiggly where they weren’t, gangly, pear-shaped, curvaceous, and every other variation of the female form. For some girls—girls whose breasts were not big enough, their stomachs not flat enough, their thighs not toned enough—the minute-long walk down the red carpet was likely the longest walk of their lives. The audience cheered, even whistled, for some contestants; for others, there was only awkward silence. Meanwhile, the judges—five men and four women—scrutinized each girl’s figure, making notations. The swimsuit competition may have been the pageant’s cruelest moment, trying to turn teenage girls prematurely into women, but it was also its most honest. Beauty—or the judges’ idea of beauty—was assessed and scored without sentimentality.

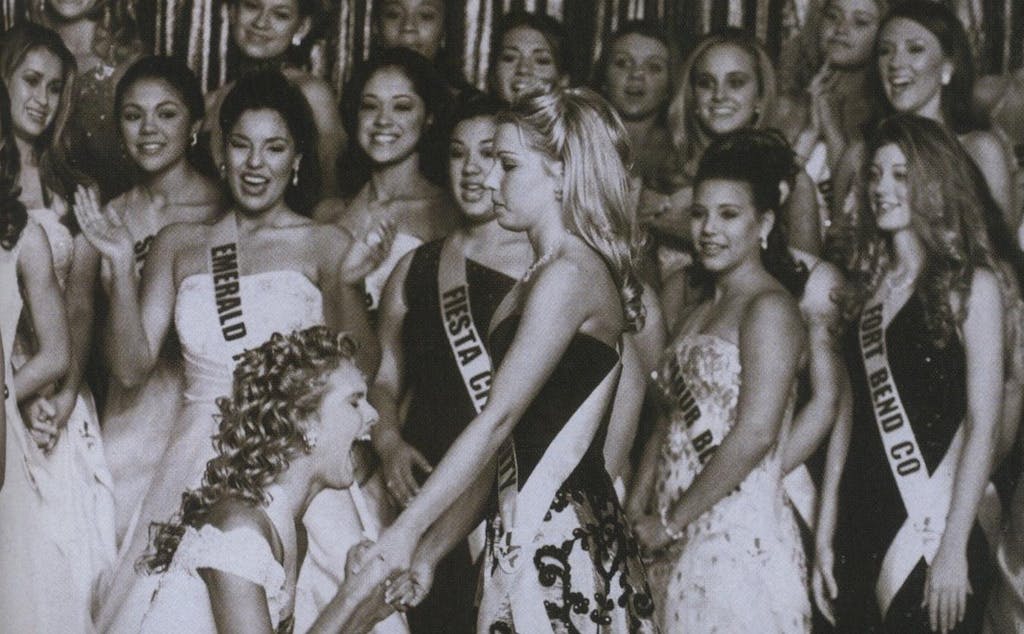

That night, Ashley strode confidently down the runway, smiling, and she did not trip. She was not the most graceful girl in the pageant nor did she have the most elaborate dress, but she stood out onstage; in pageant parlance, she “sparkled.” Her mother watched her and wiped away tears. After the show, when Ashley stood in the lobby with the other girls, waiting for the elevator, a little girl who had been sitting in the audience approached her, holding out a Miss Texas Teen USA 2003 program. “Excuse me,” the girl said to Ashley. “Can I have your autograph?”

AT NOON ON THE LAST DAY of the beauty pageant, one hour before the final competition was slated to begin, Bria Wall was being attended to by her hair and makeup specialists in a suite on the hotel’s tenth floor. Her blond hair had been washed that morning with bottled water, and her makeup had been applied with the same exacting attention to detail. (“We work hard to make the girls look natural,” her coach, former 1990 Miss Texas Teen USA runner-up Melissa King, explained.) The previous night, Bria had won the Most Photogenic award, which carried no points but was sometimes awarded to the future winner. It seemed like a good sign, and when it was time for Bria to go downstairs for the finals, her coach gripped her hands and stared at her intently. “I know you’re going to win,” Melissa said. At the precise moment at which Bria’s eyes began to water, her makeup artist darted across the room, where she tilted Bria’s head back, pressed her false eyelashes with her thumbs, and blew on her tears. Her father, Rick, watched from the couch in amazement. “I always thought I would be going to high school football games,” he told me.

Downstairs in the dressing room, Tye Felan sat in the corner in a hot-pink strapless dress, alone, her head bowed in prayer. She had the placid air of a competitor who is in the zone; her eyes shut, she silently mouthed the words for divine assistance. Around her, the room was frantic with girls stuffing their bras and practicing their dance moves and slicking Vaseline across their teeth. Ashley stood in front of a mirror in a red cocktail dress, professionally made-up again, smoothing her hair. When I asked her how she was, she held out her hands, which shook. “Nervous,” she said. The show was about to begin. Girls lined up by contestant number in the hallway that led to the stage, their high heels clicking against the linoleum. Cheers drifted from the ballroom down to where the girls stood listening in the wings. “And now, Miss Texas Teen USA 2003!” roared the announcer. The contestants paraded onto the stage, and as the song “The Rhythm of the Night” swelled, the girls performed the opening dance number without a hitch. The “parade of cities” was next, in which each girl was introduced by title as she strode down the catwalk. The audience—mostly family and friends—clapped and shrieked appreciatively. Then it was time to announce the top fifteen (or the top sixteen, as it turned out, because there was a tie).

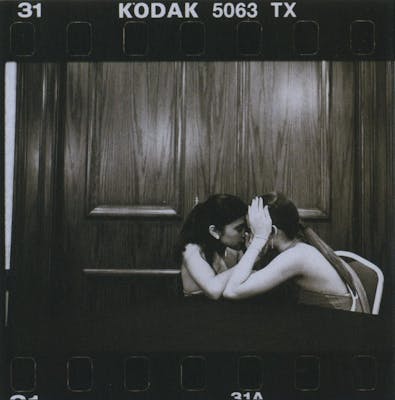

“All right, may I have the envelope, please?” said the master of ceremonies, an ebullient man named Dan O’Rourke. “Let’s get started with our semifinalists, in no particular order.” All 117 contestants stood on risers behind him. One girl’s heart beat so furiously that her pulse was visible beneath her dress; other girls’ sashes trembled. O’Rourke called out the top sixteen’s names—”Semifinalist number ten, Miss Bayou City, Bria Wall! Semifinalist number eleven, Miss Houston, Tye Felan!”—until he reached the end. “Sorry, girls, just one name left. That’s the way it goes. And it’s you, Miss South Shore, Veronica Grabowski!” Ashley Swanson’s name was not called. She and one hundred other girls filed off the stage in silence, looking wobbly. Most kept their composure until later, when they could disassemble in the privacy of their mother’s hotel room. A few girls broke down backstage. A sixteen-year-old girl from Lubbock sat in a white ball gown, sobbing, inconsolable even as two girls bent over her, offering encouraging words. One of the pageant’s few black contestants sat in the back of the dressing room, shaking her head. “Every year, they pick a blonde,” she said.

Ashley kneeled on the dressing room floor in front of the closed-circuit TV, watching the pageant unfold. “Well, that’s that,” she said. “I was dead-set on not getting it, but after everything that happened—” For a moment, her eyes watered and she looked as if she might cry. She sucked in her breath. “I’m just glad I can take these off! Phew,” she said, slipping off her heels.

Inside the ballroom, the top sixteen were soon winnowed down to a top five, with Bria and Tye still standing. Each of the five finalists was instructed to pick a question out of a fishbowl. Bria went first, selecting, “What’s the first thing you notice about a person?” She wore a sophisticated evening gown—a black, boned duchess-satin bodice, with a metallic skirt embroidered with black vines—but when she spoke, her voice was tremulous. “Definitely first impressions count for a lot,” she said. “I definitely notice their personality. I think personality counts for everything.” Bria had been much better offstage, face-to-face. Standing next to Tye, she seemed diminished. Tye stepped up to the microphone in an elegant white tulle and satin dress trimmed in crystals. She had the kind of stage presence that made it seem as if the lights shone more brightly on her. She picked the question, “If you could go back and be any woman in history, who would it be and why?”

“Probably Patsy Cline, because she was one of the first women pioneers of country music, and country music is my love,” Tye said with serene self-possession. “And I think she did a lot for women in general, not just the country music industry. She set a standard, and women are still trying to go over that.”

The judges would finally narrow it down to Bria and Tye. The two girls stood onstage, hands joined, heads bowed—just as they had eight months earlier, at the Miss Houston Teen USA pageant. They both looked as if they might faint. “The first runner-up is Miss Bayou City!” yelled Dan O’Rourke. “Tye Felan, Miss Houston, you’re our Miss Texas Teen USA for 2003!” And there she was, the girl who looked—especially once the crown rested on her head—like the womanly ideal. In a beauty pageant, it is hard to beat myth. Standing before the crowd that night, Bria’s game face crumbled. Her shoulders sank, and her blue eyes, usually so full of vitality, went flat. She posed for a few photos and congratulated Tye, but her smile was strained, and she finally broke away to see her mother. The last time I saw her, Bria was walking down an empty backstage hallway, crying, her mother’s arms wrapped tightly around her. As they walked, her mother smoothed her hair and kissed her, over and over again. Bria sounded as if she were in physical pain. She had been coached to win. No one had told her what it would feel like to lose.

THE DAY AFTER THE BEAUTY PAGEANT, Ashley returned to Pampa. Life went on as usual. She wrote an essay on the significance of the color red in The Scarlet Letter for her AP English class, and she played her flute in the Pampa High School Band. To kill time on the weekends, she and her friends cruised the main drag of Pampa and watched the mud- bogging competitions down by the lake, where kids plowed through the muck in their jacked-up Jeeps and 4×4’s. If the sky was clear, they drove out to the oil fields, where they lay in the back of their pickups and stared up at the stars. Later, I asked Ashley what she thought about the beauty pageant, in retrospect. “It doesn’t bother me at all that I didn’t make the top fifteen,” she wrote in an e-mail. “All that meant was that I didn’t have to go out in front of those people again in my swimsuit! I think I’m going to go back next year. I’ve convinced my best friend here, Melissa Scobee, to go with me. I was thinking on the way home about the whole learning to be a girl bit, and it was almost insulting to me in a way, because I do know how to dress nice and put on makeup and do my hair and all that good jazz, but when I got there, it didn’t seem like that was enough. I needed to be more, if you know what I mean. A lot of those girls were, like, flaunting their money, I guess you could say, by all the really nice and expensive clothes they wore during rehearsal. I don’t really have the money to do that, but I’m still very picky about how I look. Everything has to match, and my hair has to be perfect. The only reason why I don’t wear makeup is because it’s time-consuming and it’s a pain in the butt to get off, and besides that, I know that I don’t need it.”

Ashley explained that it had been a long drive back to Pampa. “Before I knew it, we were six hours from Houston, and six hours from home,” she wrote. “Anyway, it’s almost 11:00 and I need to go blow-dry my hair.”