I was about to make it past level 147 of Candy Crush when I discovered the Texas Archive of the Moving Image. Suddenly there was a powerful new contender in my distraction derby. It may have been hours passing, it may have been months, while I stared at my computer screen, clicking again and again on the “Random Film” tab of this confoundingly absorbing website.

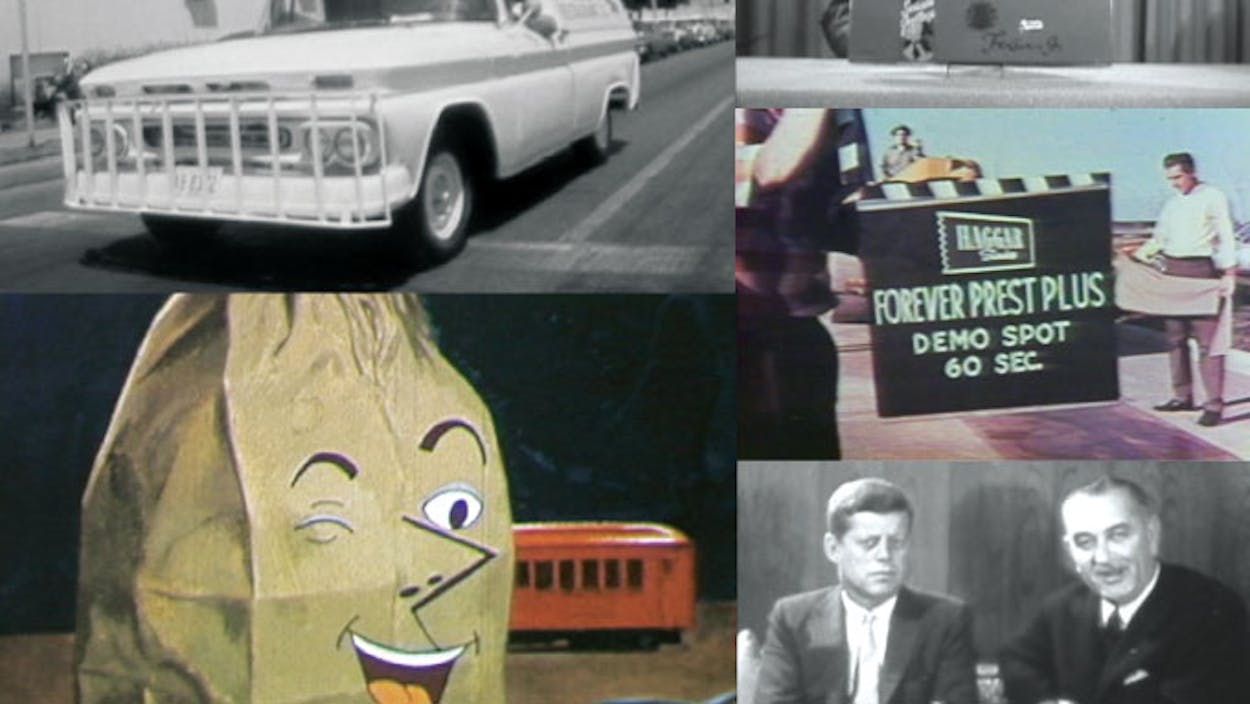

Among the things I watched without quite understanding why I was doing so: a sixties-era black and white film—only a minute and twenty-seven seconds long, though it feels eternal—of a truck driving through the streets of Austin with a revolving sign on top that reads “All the Mexican Food You Can Eat $1.25”; two promotional films from the Texas Forest Service, entitled “Paper and I” and “Which He Hath Planted”; a commercial for Haggar Forever Prest Plus Slacks in which a pair of pants emerges wrinkle-free from beneath a 20,000-pound steamroller; an interview with Texas sage J. Frank Dobie, conducted by Austin broadcast personality Cactus Pryor five days after the Kennedy assassination, in which Dobie, in all his chiseled eminence, hands down his verdict on Lee Harvey Oswald (“He was a poor thinker”); and a 1960 Texas Department of Public Safety documentary on Padre Island whose insights include the misinformation that Vikings had visited the Texas coast and that “cannibal Indians used to waylay shipwrecked sailors and then chase them up and down the island one at a time as the menu indicated.”

Caroline Frick, a professor in the University of Texas’s Radio-Television-Film department who is the founder and director of the archive, thinks of the site as a “curated YouTube for Texas.” I think of it as quicksand. Once you click, down you sink. As far as I can tell, there’s no bottom to it. Since the nonprofit website was established, in 2002, Frick and her small staff have digitized “tens of thousands of hours of content—no, way more than that!” In partnership with the Texas Film Commission, the archive conducts an ongoing Texas Film Round-Up to encourage people to bring in their old films and videos before they corrode or end up in a dumpster. But the website is not just a flood of raw visual data. Everything that appears on it is researched and annotated. We learn, for instance, that the Snake King of Brownsville—shown joyfully wrangling rattlesnakes in a 1914 film clip—had a son who went on to become the World’s Youngest Wild Animal Trainer.

Frick grew up in Kansas and in Washington, D.C., but her interest in Texas history was fed by family lore that her great-great-grandfather was deputized as a Texas Ranger to ride in pursuit of the Comanche who captured Cynthia Ann Parker. Before coming to UT, she was a film curator and an archivist for Warner Bros. and the Library of Congress, but she was drawn to the idea of identifying and preserving the regional films that nobody in Hollywood or Washington had much interest in. “I found it fascinating that while there’s been an incredibly rich history of media-making in this state, there hadn’t been any attempt to create a central hub for preserving these materials,” she says.

The materials she’s talking about are mostly the scraggly underbrush of the film and video world: industrial films, commercials, public service announcements, home movies, and local television outtakes. There are few traditional feature films, which are generally not in the public domain, but there are plenty of interviews with actors and filmmakers, many of them conducted by permed and pantsuited Austin TV host Carolyn Jackson. (“Do you think,” she asks producer Gary Kurtz in 1977 about a surprise hit called Star Wars, “that this may be the beginning of a new trend in movies?”) And there is the idiosyncratic work of Melton Barker, an itinerant filmmaker of the thirties and forties who created a sturdy Our Gang knockoff, Kidnappers Foil, which he shot again and again in places like Childress and San Saba, directing a supremely untalented cast of local children.

Archival moving images such as these are both immediate and distancing. They are capable of bringing the remote past to life but also of seizing what you once experienced as the present and endowing it with startling mustiness. Partly this is because film and videotape are so vulnerable to deterioration. A sixties home movie of a trip to Carlsbad Caverns might have the same ancient flickering quality as moving pictures of the aftermath of the 1900 Galveston hurricane. Watching footage from the vintage of your own span on earth—with its washed-out colors and curious clothes and hairstyles—establishes an odd temporal empathy. The silent, jerkily moving figures captured by early movie cameras once seemed merely the quaint denizens of history. Now, you realize with a shock, you’re one of them.

But sometimes the past seems most remote when the production standards are reasonably modern. One of the most fascinating things to watch on the archive’s website is the way people used to address the camera in commercials and public service announcements. The prevailing attitude is one of stentorian suspicion. Watch John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson speaking to Texas voters in a 1960 campaign ad: the level of unnaturalness is spooky. They don’t know where to look, what to do with their hands, how to modulate their voices so that they appear to be speaking to the viewers rather than to a blank wall.

What is most striking, however, is that they don’t care to know. Alpha males of the fifties and sixties didn’t face the camera, they confronted it with an almost hostile intensity, as if a full embrace of this new medium might mean surrendering their dignity to a silly fad. One of my favorite artifacts on the site is a series of takes of David Lamme, the head of an Austin candy company, as he attempts to film a television commercial. He stands at a table behind a box of candy, wearing a dark sack suit, his hair slicked back, his eyes fixed in a thousand-yard stare.

“I’m David Lamme of Lammes Candies. We’ll mail this one-pound box of Texas chewy pecan pralines for you anywhere in the United States for just two-fifty.” He says it over and over, take after take, never changing his tone of voice. He looks and sounds as somber as somebody delivering a eulogy for his best friend. The stiffness feels deliberate, even defiant. He will remain as impassive and unrevealing as necessary to keep the television camera from robbing his soul.

The archive is a treasure trove of such vanished mores. The Texas accents you hear from public officials tend to be stark and forthright, uncorrupted by the cosmopolitan blending of our era. A Southwest Airlines commercial from 1971 boldly presents the queasy spectacle of a trio of flight attendants striding across the tarmac in hot pants and calf-high white boots. “Remember what it was like before Southwest Airlines?” one of them purrs. “You didn’t have hostesses in hot pants.” Then she says, “Remember?” in a taunting voice meant to make you wonder how civilization could have ever been so backward. In political propaganda such as 1954’s “The Port Arthur Story,” you find yourself smack-dab in the paranoid hothouse of Red Scare Texas. Governor Allan Shivers’s notorious reelection ad purports to show a city devastated by a labor strike. Over footage of nearly deserted downtown streets, the narrator informs us that after a “Communist-dominated plot to take over Texas industry,” Port Arthur has become “a ghost city” where “children don’t play anymore. Women don’t shop. . . . Nobody smiles.”

In “The Port Arthur Story,” you witness a Texas that is closing in on itself, fouling the atmosphere with rancor and suspicion, and you can hear the countdown clock ticking toward the Kennedy assassination. But the archive is a time machine that runs in both directions. Back up a few years and you’ll find “Looking Ahead to Greater Horizons,” a fund-raising film for Abilene Christian College, made just after the end of World War II. The buoyancy and optimism it projects is stirring, even to viewers who know how the rest of the twentieth century turned out. Young veterans are flooding into the classroom, reclaiming their destiny on the dusty ACC campus. We hear a full-throated chorus singing the school’s alma mater, and we are introduced to eminent professors in the fields of study that most crucially matter when it comes to preparing an individual for “lives of greater usefulness”: the Bible, agriculture, and home economics.

“Looking Ahead to Greater Horizons” suffers from the inevitable defect of being a product of its age. The film seems naive to us, too full of confidence that its eyeblink of time will last forever. But that’s the power of the Texas Archive of the Moving Image: it unfreezes time, challenges our memories of who we thought we were, and holds everything up to the harsh light of now.