This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

To an Austin newcomer in the early seventies, the One Knite Tavern was a wonderfully dark, forbidding place. The junk hanging from the ceiling and the smell of stale beer and vomit that hit your nostrils at the door are the only distinctive attributes I can recall. But I didn’t go for the ambience. The One Knite was a blues joint, and in a city full of six-string gunslingers, the best guitarists played the blues. In that select circle, none were as impressive as the Vaughans, Jimmie Lee and his younger brother, Stevie Ray.

Both had played in rock bands in Dallas, where they were pursued by record moguls offering big-money deals. Instead, they drifted to Austin to immerse themselves in a purer kind of music. Jimmie was the cool, detached lead guitarist for the Storm who played a classic economical style that evoked blues heroes like Guitar Slim, Freddy King, and T-Bone Walker. Little Stevie, who played lead in the Nightcrawlers and later became second guitarist to Denny Freeman in the Cobras, was the runty kid brother with the huge hands who was scrambling to develop a signature sound by mixing unequal parts of Howlin’ Wolf and Jimi Hendrix.

Over the next few years, part of the fun of following the Vaughans was arguing which brother was better and who would make it big first. Jimmie went on to found the Fabulous Thunderbirds while Stevie honed his chops with local blues veteran W. C. Clark as part of the Triple Threat Revue before starting his own group, Double Trouble. In the process, both brothers were getting tutorials from such recognized masters as Albert Collins, Buddy Guy, Albert King, and Muddy Waters, all of whom performed at Antone’s blues club, where both Jimmie’s and Stevie’s groups were house bands.

They didn’t just play the blues, either, but embraced the whiskey-women-and-bad-luck lifestyle of the hard-bitten characters in their songs. Stevie depended on friends for a place to sleep and bummed rides to get around. His only possession was his Stratocaster guitar—and that was frequently in the pawnshop. By the end of the decade, both brothers played like they had been born black and brimming with soul. Jimmie and the Thunderbirds built a cult following across the country and Europe, and Stevie climbed to the top of the Austin bar-band circuit. He did it with drummer Chris Layton and, later, bassist Tommy Shannon, who together made up a powerful rhythm section that afforded Stevie plenty of space to fill with his prowess. He sang in a husky voice that sounded like it came from an elderly Mississippi sharecropper, not some impressionable kid.

Stevie’s first big break came with the invitation to play the prestigious Montreux (Switzerland) Jazz Festival in 1982. What Austin clubgoers had taken for granted (usually for a $2 cover charge) knocked out the sophisticated crowd. Among them were Jackson Browne, who offered Vaughan free use of his studio, and David Bowie, who enlisted him to play lead on what would be the hit single “Let’s Dance.” The transition from small clubs and sleeping on borrowed mattresses to concert halls and limousines was rapid. Stevie’s wild pyrotechnics sparked comparisons to Hendrix. His deep background in the blues earned him the respect of his peers.

By 1984 Stevie’s success had clearly eclipsed his brother’s. His debut album, Texas Flood, was nominated for a Grammy. The follow-up, Couldn’t Stand the Weather, sold more than a million copies. It seemed like the only thing that could keep Stevie from realizing his potential was himself. The rock and roll lifestyle was taking a heavy toll. By 1986 he had almost killed himself with alcohol and cocaine. Instead, a nervous breakdown saved his life. He kicked his bad habits and moved back to Dallas to be nearer to his mother, Martha. He proceeded to defy the old music-business notion that when the truly talented go straight, they sacrifice their creative energy: Stevie became more focused, both as a player and as a person.

Somewhere along the way, sibling rivalry turned into mutual admiration. It was not unusual to see Jimmie sitting in on one of Stevie’s shows or Stevie walking on at a Thunderbirds’ gig.

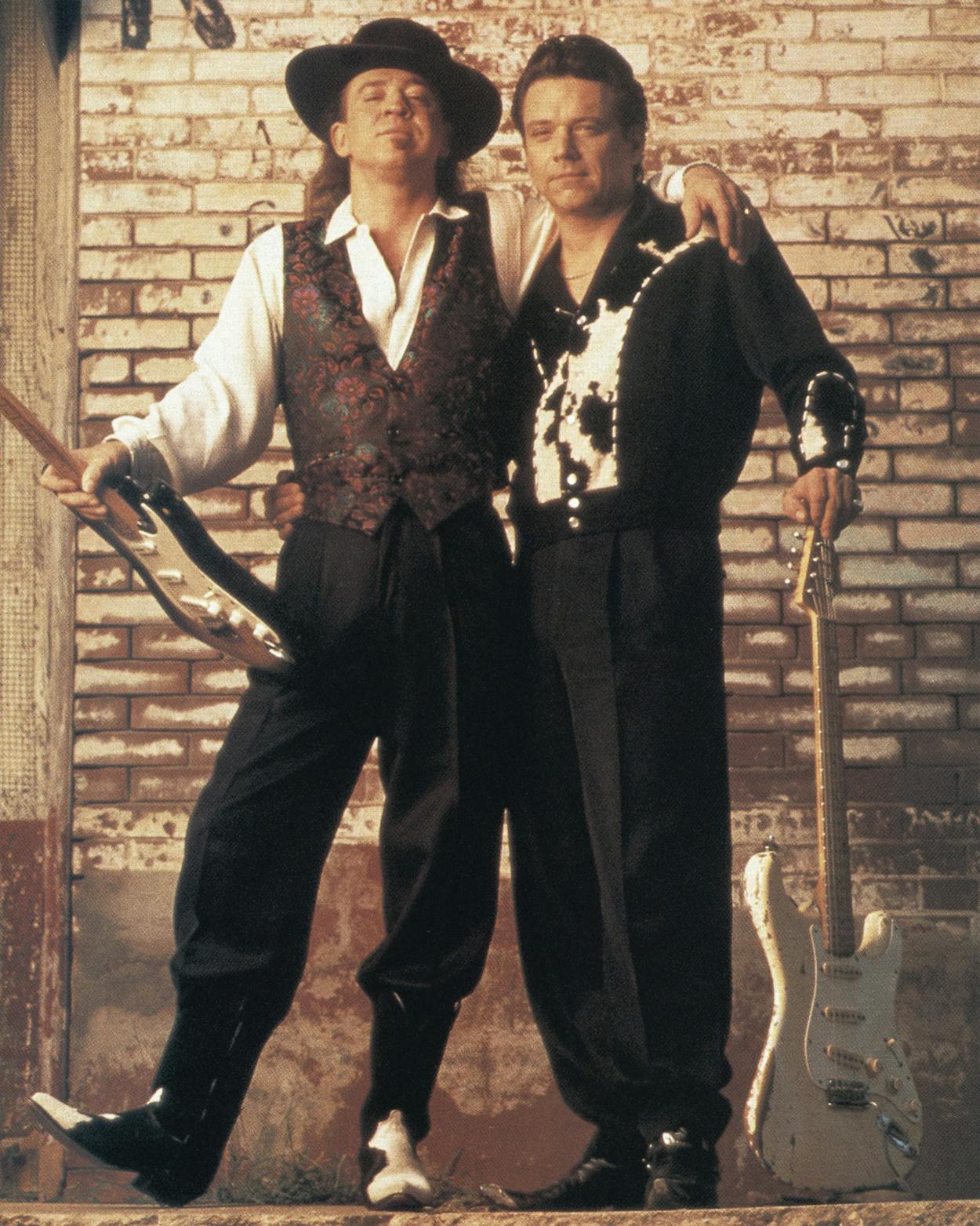

Last summer the brothers temporarily set aside their respective careers to collaborate on Family Style, which was to be released in late September. The experience proved so uplifting that Jimmie announced he was quitting the Thunderbirds. He could look forward to touring and promoting the album with Stevie.

But it was not to be. Just after one in the morning on August 27—following an outdoor concert in southern Wisconsin featuring guitar heroes Eric Clapton, Robert Cray, Buddy Guy, and the Vaughan brothers in which Clapton introduced Stevie to the crowd of 25,000 as “the world’s greatest guitarist”—a helicopter carrying Stevie slammed into a hillside, instantly killing all on board.

Death heaped atop prodigious talent such as his means immediate enshrinement as a rock legend. But we will never know how much more he could have accomplished, not as a bluesman or a guitar god, but as an artist in the truest sense and as a gentle, compassionate human being who had beaten back his demons. What remains is the album he always wanted to make with his brother, his own five albums, countless tapes of his work, and memories. Many will remember him as the gaunt figure in the bolero hat who mesmerized thousands with an uncompromised skill and showmanship that could only have come from Texas. I prefer to recall the scrawny kid at the One Knite waiting impatiently for his turn to play so he could breathe fire and passion into his instrument. At 35, Stevie Ray Vaughan may have died too young, but it was a hell of a ride.

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Blues

- Stevie Ray Vaughan

- Dallas