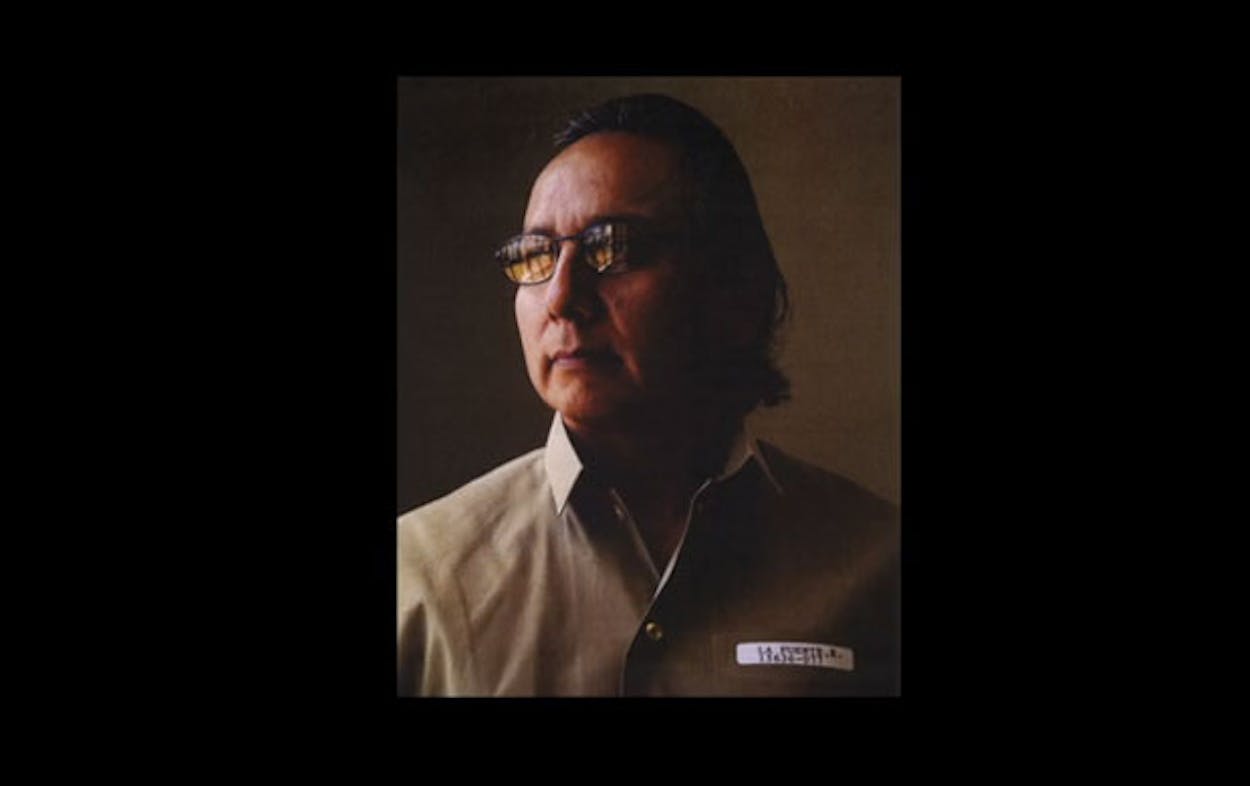

I’ve written many criminal justice stories for Texas Monthly over the past thirteen years, and many of those involved inmates who claimed they were innocent. Some, I’m pretty sure, were guilty; others, I became convinced, were not. Almost all of the deserving ones eventually got justice. Only one of them has never received his due. His name is Richard LaFuente and he was wrongly convicted of being part of the murder of a policeman on a North Dakota Indian reservation 29 years ago. He was convicted along with ten others and sent to federal prison, but every one of the others was freed long ago. Only LaFuente remains—and all because he won’t confess to a murder he had nothing to do with. All because he won’t show false remorse for something he didn’t do.

I’ve written about him twice; the first story, in October 2006, laid out the bizarre, hard-to-believe case against him. It’s a complicated story, but the short version is this: In the summer of 1983, LaFuente, then just 25 years old, went with his brother-in-law, John Perez, to visit some relatives on the Devils Lake Sioux reservation (now the Spirit Lake Nation), in North Dakota (LaFuente is half Sioux, half Mexican-American). While they were there, on August 28, a former policeman named Eddie Peltier was found dead on a rural highway, the apparent victim of a hit-and-run.

Two and a half years later LaFuente was arrested for Peltier’s murder. Witnesses at the rez said that on August 28 there had been a big party that led to a big fight. Four witnesses said they had seen a mob of men beat Peltier, while one said she had seen LaFuente, with assistance from Perez, run Peltier over in his souped-up El Camino. LaFuente, Perez, and nine local men went on trial for murder. Not a shred of physical evidence tied any of them to the crime, and all but one of the defendants had an alibi, but the four witnesses carried the day. All eleven men were found guilty, and the two Texans got the longest sentences: twenty years for Perez and life for LaFuente.

Soon, though, the truth began to come out. There had been no party that night and no fight. Two of the witnesses recanted and said they had been threatened by James Yankton, a Bureau of Indian Affairs cop whose large family basically ran the rez. Within four years of the verdict, nine of the defendants had their convictions thrown out because of insufficient evidence. In 1999 Perez was paroled, and only LaFuente remained in prison (by then he’d been transferred to a federal facility in Fort Worth). Thirteen years later, he’s still there. “He never had a fair trial,” I wrote, “the courts have said so twice. The truth is, like Eddie, Richard never had a chance. It would be a grand gesture if the government, which bent every effort to convict him, finally gave him one.”

I wrote a second story earlier this year, in January; this one detailed how bullheaded and unresponsive the federal system is for a man with such a perfect case of actual innocence. “It’s so overwhelming what they’ve done to me,” he told me for the story. “But I’m not gonna let them ruin me or destroy my life any more than they already did.”

Unlike many of the men I’ve done stories on, Richard LaFuente is a kind, decent person. He was the wrong man in the wrong place at the wrong time—and he has paid for it with his life—26 years of it. He’s a grandfather now, and his daughters bring their children to visit him. He’s been turned down for parole so many times now he doesn’t keep track.

And now a man named Todd Trotter is trying to make a documentary about the case. Trotter has worked on a bunch of TV documentaries; Incident at Devils Lake will be his first film on his own. Trotter has been researching the case for a couple of years now and is ready to go to the Spirit Lake Nation in North Dakota to film the story. All he needs is money. Trotter just started a Kickstarter campaign to try and raise $50,000. For more evidence and information, visit his website.