This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

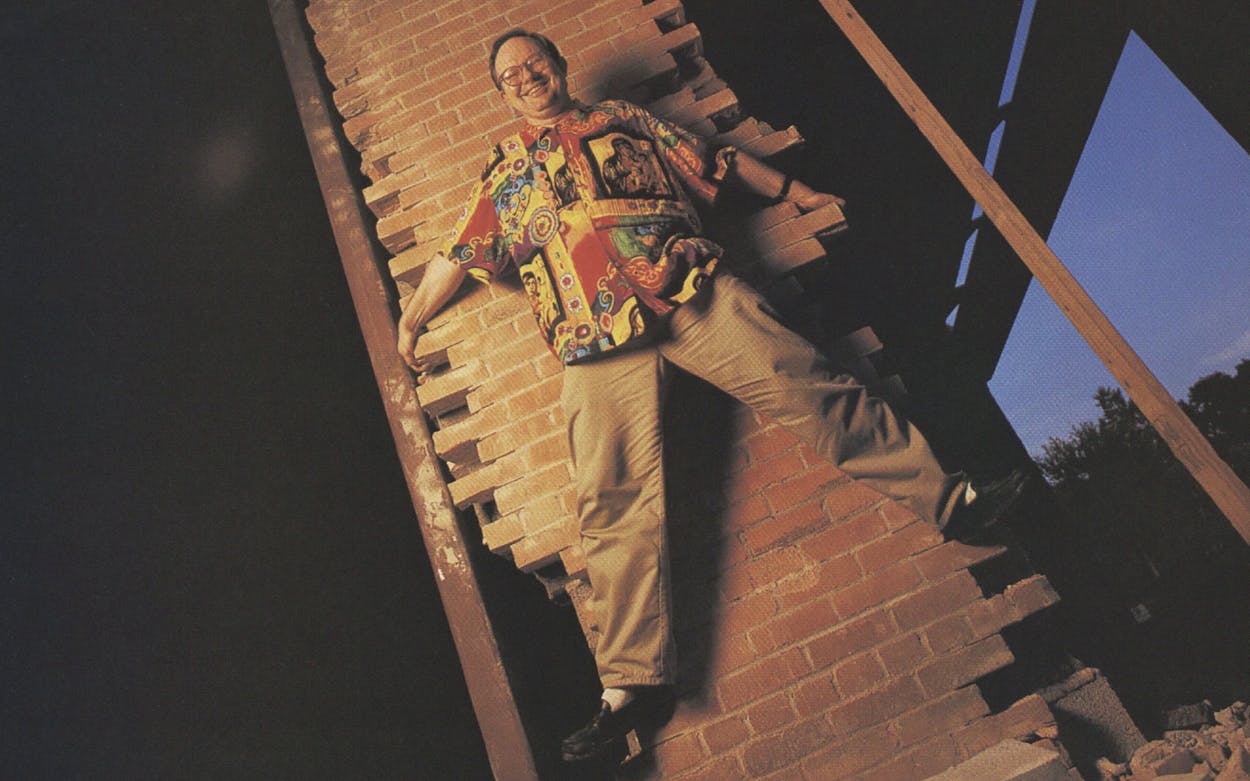

If there’s one thing that Rick Brettell, the 45-year-old boyish-faced former director of the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA), has been able to do, it’s generate controversy—even before his arrest for allegedly fondling an undercover police officer in a Dallas park known as a homosexual hangout. Since his 1988 arrival from the Art Institute of Chicago, where he was a celebrated curator, he has been a thorn in the side of Dallas, a scholar and a showman with a rapid-fire voice and tireless mind who has never hesitated to go against the city’s button-down arts establishment. Soon after taking over the DMA, for example, he publicly announced that it was among “the second tier of American museums.” Then there was the brouhaha when the papers reported that he had suggested dismantling the Wendy and Emery Reves Collection of decorative art and Impressionist paintings, which was displayed in the museum in an exact replica of the Reveses’ Mediterranean villa, right down to the placement of Emery’s bedroom slippers beside the bed.

Brettell tried exciting things: He tore out the museum’s entire permanent exhibit to present a major touring show of Mexican art. And he tried shocking things: One DMA exhibit featured paintings of body parts on glass, which some museum patrons labeled pornographic. For the first time in years, people in Dallas paid attention to the arts. Then, in October 1992, he really got the city talking. The art world genius, married for nearly twenty years, found his reputation in tatters. He pleaded no contest to charges of public lewdness and resigned under pressure from the museum’s board of directors.

The scandal, especially humiliating in a city as image-conscious as Dallas, would have sent most anyone else hightailing it out of town in hopes of resurrecting his career elsewhere. But not Rick Brettell. He stayed in Dallas and accepted a temporary job with the DMA as a consultant so that he could complete the mammoth project he had started, which he believed would dramatically change the DMA’s limited regional reputation. “I had things to do,” Brettell says succinctly, refusing to make any comment at all about the scandal. “My personal life is none of anyone’s business. People should judge me on my work.”

This past year, the public and the art critics got a chance to see exactly what Brettell had been doing. In a new 140,000-square-foot addition to the DMA, Brettell established the Museum of the Americas, a provocative exhibit unlike anything in any museum in the world. With three thousand works of art ranging from pre-Columbian sculptures to World War II-era American paintings, the Museum of the Americas was Brettell’s attempt to make visitors see American art as more than an offshoot of European art. “I wanted to show the connection,” says Brettell, “between the art of the great ancient Central American civilizations, the art of such indigenous cultures as the North American Indians, the art that emerged from the Spanish and British colonies, as well as the twentieth-century art produced in the United States.”

After an impressive introduction to the exhibit—a long ascent up a grand staircase into a small, dimly lit room holding nine objects that illustrate creation myths from cultures of the Western Hemisphere—visitors walk through other rooms that describe a sweeping history, ending with a display of Mexican and Canadian modernist works hanging logically beside those of Georgia O’Keeffe and Thomas Hart Benton. While the Museum of the Americas has been both praised and panned by the critics, the fact is, it hasn’t been ignored. Writers from various art publications, the New York Times, and even the Wall Street Journal have come to Dallas to weigh in on Brettell’s vision. “And isn’t that the point of a museum?” he asks. “Shouldn’t it be a place to ask questions, a place to make us question our very culture? ”

Brettell came to Dallas with great fanfare. He and his wife, Caroline, who chairs the anthropology department at Southern Methodist University, were considered two of the best dinner-party guests in Dallas. His charm and ability to get normally staid businessmen excited about art helped him increase the DMA’s endowment from $14 million to $34 million in just four years. He presented a show of art by black americans that brought in people who previously had never come through the DMA’s door. In a more traditional vein, he garnered international attention for the DMA when he organized a blockbuster exhibit of Pissarro paintings.

But Brettell was also known as a poor administrator; he was abrasive to employees and notorious for not returning phone calls. When he was charged with public lewdness, the museum board had had enough. It gave him time to finish the Museum of the Americas installation, then let him go after the exhibit opened.

Some observers saw Brettell’s arrest as the self-destructive end to a once-brilliant career; others saw his forced resignation as a sign of the Dallas establishment’s provincial nature. Brettell ignored public opinion and simply moved on to other projects. He has put together a Cezanne-Pissarro exhibit that will be shown in museums in London, Paris, and Los Angeles. He is creating a show on the Polynesian paintings of Paul Gauguin for a museum in Auckland, New Zealand. He is co-writing a scholarly book on Georgia O’Keeffe’s home in Abiquiu, New Mexico. He has accepted appointments to lecture at Yale and Harvard. But what he says he’s most excited about is his supervisory role in the creation of the McKinney Avenue Contemporary, Dallas’ second attempt at a major contemporary arts center, which is opening this fall. As an alternative to the DMA, the 15,000-square-foot MAC, as it will be known, “will become a vanguard urban place that hasn’t been seen since the fifties,” says Brettell. “It will have not only galleries but also a cafe, a cinema, and a bookshop, even a space for performances. Yes, it will be the kind of place where you are forced to ask questions.”

It is certainly ironic that the man who was brought down in one of Dallas’ messier scandals could end up being the man who revitalizes the art scene in Dallas. Brettell says he and his wife have no plans to leave the city. “I love it here. And I love the chance to contribute something to the intellectual life of the city,” he says, showing the same cheerful confidence he had when he first came to town. “I listen to people disparage Dallas for its lack of an artistic scene, but I sense a great vibrancy here. There are many artists in Texas who are drawn here because it’s an anti-center and not as elitist as New York. The creativity here can challenge us and make us better. Now, we have a responsibility to go find it. ”

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Dallas