This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

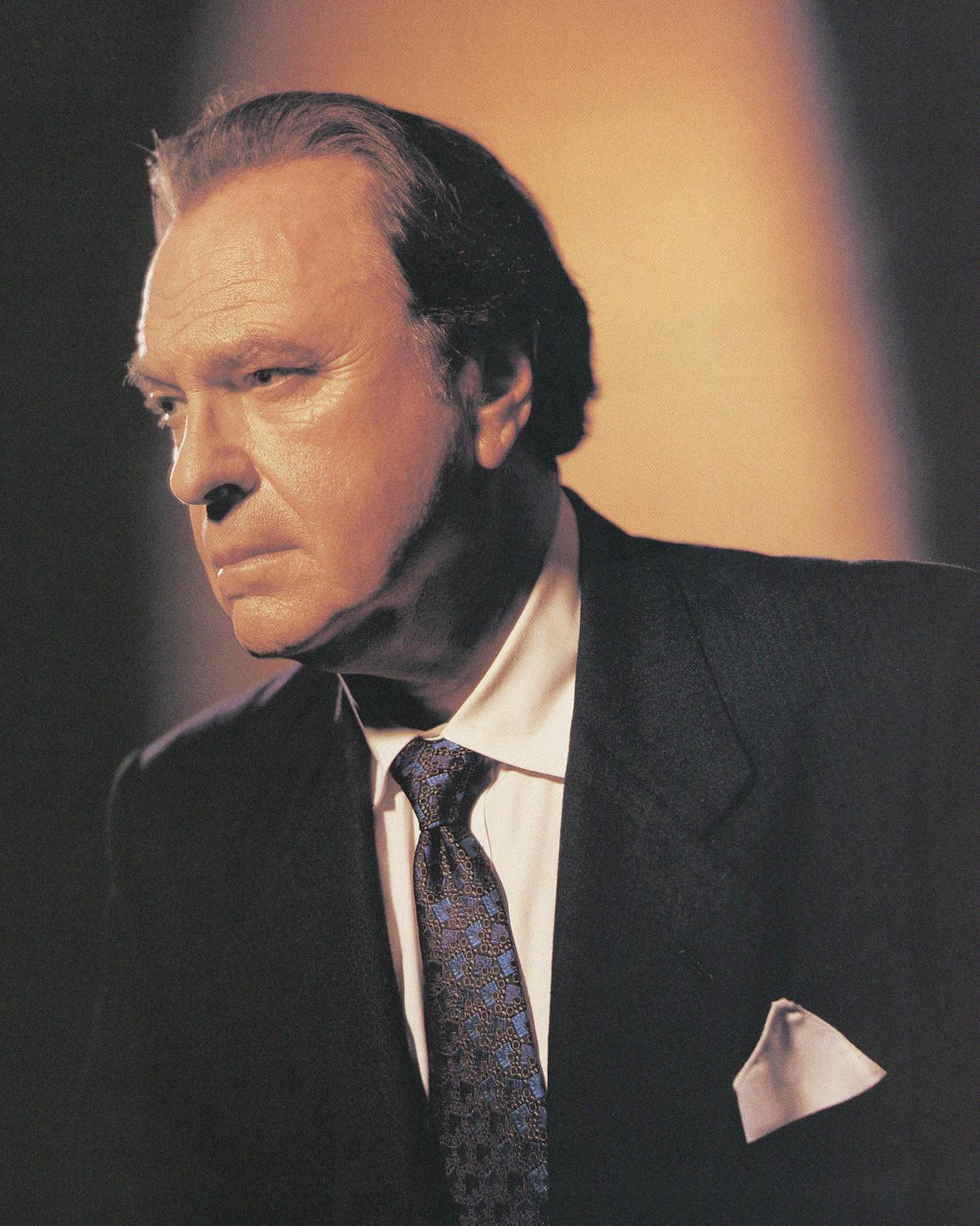

Rip Torn has been waiting in his dressing room across from Sound Stage 11 since a quarter after seven, gearing up to play his role on The Larry Sanders Show, but three hours later they still haven’t called him to the set. Rip is starting to get edgy. He has had his morning shot of tequila, the one drink that he allows himself during working hours, and has changed from the ratty Texaco-green trousers and plaid fishing shirt that he wears at rehearsals into the dark business suit and hairpiece of Artie, the profane, street-smart, slightly mad “producer” of the make-believe TV talk show that parodies TV talk shows. The consummate perfectionist, Rip modeled his character on several legendary show business tyrants, including Fred de Cordova, the longtime producer of the Tonight show, and Louis B. Mayer, whose biography Merchant of Dreams rests on the coffee table in Rip’s dressing room.

“I imagine Artie grew up in New York with a Sicilian socialist father and a Russian mother,” Rip says, settling into an overstuffed chair and shoving the Mayer bio and a stack of scripts to one side of the table to make room for his feet. “He probably did some illegal work in his youth. He’s still not allowed below Fourteenth Street: He’s got a history down there. But he went in the Army and probably ended up a colonel in intelligence. He’s a good actor—Shakespearean, played Shaw, O’Neill, Tennessee Williams. Worked everything from carnival to opera. A legendary pro. Knows everything about the business: lighting, makeup, wardrobe, producing, directing, everything. And he loves show business, absolutely loves it!” Except for the fact that Rip Torn grew up in Texas, of Czech, French, and German stock, and was a lieutenant in the military police, not a colonel in intelligence, the actor could almost be describing himself. Talk about a guy with a history.

After a time, Rip walks to the window and looks across Republic Avenue, the central passageway that runs between the rows of hangar-size sound stages that make up CBS Studio Center, where the Sanders show is filmed. His mood is darkening. It’s not the waiting that he minds; it’s what the waiting symbolizes: a lack of respect. Rip has learned to wait, learned to pace himself, learned to control (or at least harness) his famous temper. For years Rip kept a sign on the wall of his dressing room that read: “They treat me like a mushroom. They keep me in the dark and feed me shit.” The sign is gone, but the memory lingers in the dark recesses of his paranoia, cuing the old and still powerful demons that Rip has wrestled all of his career. The demons are mostly his own creations—he sees enemies everywhere and suspects that friends secretly begrudge him his success—but even illusory demons are a menace in a world of make-believe.

For nearly four decades, Rip Torn has been a major talent in American theater and film, one of the four or five best actors of an extraordinary generation that included Brando, Newman, McQueen, and Ben Gazzara. Rip trained at Lee Strasberg’s legendary Actors Studio in New York in the fifties and was a star on Broadway before many of the people associated with The Larry Sanders Show were born. Even so, he has never felt secure. “A critic asked me one time, ‘How does it feel being a god up there on the stage or on-screen?’ ” Rip says, his eyes narrowing in defiance. “And I told him, ‘All I know is that in five or six weeks, I’ll be out looking for a job.’ ” Had he been less talented—less of a presence, less intimidating to inferior actors and directors, and less stubborn in his compulsion to exercise his artistic temperament—Torn probably would have been a star. Instead, his career has been a constant struggle, a series of lost chances, near misses, and battles with producers and directors that gained him a reputation as an actor who is “difficult” to work with. Though this reputation is greatly exaggerated and mostly unfair, Torn has carried it for so long that it is part of his permanent baggage.

A few minutes before noon there is a pounding on the dressing room door, and a woman’s impatient voice calls out, “They’re waiting for you.” As though on cue, Rip’s temper cuts in. He stands and faces the door, that trademark slow burn inching down his body until it has engulfed him like an aura of fire. He jerks open the door, squaring his shoulders and swelling his diaphragm until his presence fills the entire doorway. In a controlled bellow, he informs the hapless assistant director who has been sent to fetch him, “They are not waiting for me, young lady [he pauses for effect], I . . . am waiting . . . for them! In the future, knock once . . . and say [here his voice turns sweet as honey], ‘Mr. Torn, they’re ready for you.’ Then turn smartly, and walk back in the direction from which you came. I do not need you to escort me to the stage.”

The young woman blinks, nods, and hurries off. “That’s what they’re trained to do—wrangle actors, shoehorn them over to the stage,” he says, savoring his performance. “I won’t go for that, not at all.”

Once he is on the Larry Sanders set—back in the land of make-believe—Rip relaxes and slips comfortably into his role. He isn’t merely playing Artie; he has become Artie: the walk, the talk, the narrowing of the eyes into mean, menacing slits, ready for battle. He snatches a couple of chocolates from the craft services table and washes them down with black coffee, then walks through a final rehearsal for a scene he’s doing with guest star Jason Alexander. Alexander plays the character of George on Seinfeld, but in this scene he is playing himself—a guest appearance within a guest appearance, as it were. In this scene the ever-disingenuous and calculating Artie slaps Alexander on the shoulder after the “show” and says, “Great job, Jason! When are they going to give you your own show?” At that moment, Artie is summoned to the telephone, but he calls out as he hurries away, “I’ll be back for that answer!” Though there is nothing particularly funny about this blatant throwaway line, Rip’s timing, delivery, and facial contortions make it funny, bringing stifled snickers from an appreciative crew. Rip watches their reaction as he would the reaction of an audience during a live performance. “I use the crew as my audience,” he says. “That’s how I know if I’m nailing it.”

The Larry Sanders Show is a sitcom that makes fun of television talk shows, which means that it also makes fun of itself. The plots are mainly concerned with backstage humor among recognizable show biz types—oversexed writers who seduce script girls in the wardrobe closet, sleazy agents, a boot-licking Ed McMahon–inspired sidekick played by Jeffrey Tambor. Garry Shandling, the creator and star of the show, plays Larry Sanders as a self-centered and spineless talk-show host. Rip portrays Artie as a kill-to-win producer who recognizes that Sanders is his bread and butter but who is nevertheless genuinely fond of his boss. There are always one or two guest stars playing themselves: Movie critic Gene Siskel, for example, played Gene Siskel—overplayed, Ebert might say. While the plot of the show is basically one crisis after another, everyone in the actual production seems to be having a good time, joking, bantering, trying out new ideas. This is one of the best shows on television precisely because of the feeling that they make it up as they go. The episode that I watched them film—the one with Jason Alexander—was the third of the new season, which premiered on Home Box Office in late June. (The show airs Wednesday nights at 9:30 p.m.) If the remaining shows are as funny as the first three, The Larry Sanders Show will dominate the CableACE and other TV awards shows.

Shandling, who is a friend of writer-director Albert Brooks—they jog together near their homes in Brentwood—asked Torn to read for the role of Artie after watching his over-the-top performance in Brooks’s wonderfully offbeat comedy Defending Your Life. “Rip is naturally funny,” Shandling tells me. “He has a great talent for improvisation. He could have been a major comedic actor. I don’t know why he wasted all those years doing Hamlet and Macbeth and all that stuff.” There is a lot of good-natured give-and-take between Shandling and Torn and, apparently, good feelings. When Rip beat out his boss for the CableACE award as best actor in a comedy series, Shandling joked that for the first six episodes of the new season, the character of Artie would be in a coma. This probably would not have stopped Rip. As Robert Ward wrote a few years ago in American Film magazine, in the movie Jinxed! Torn “outacted everyone else in the picture even though for two thirds of it he played a corpse.”

Back in his dressing room at the end of the day, Rip begins to shed the presence of Artie and resume the role of Rip Torn. “This is almost like a different career,” he says, changing into his rumpled street clothes. “A lot of my friends in New York seem surprised—some of them seem pissed off—that I’ve been successful. People are saying, ‘My God, I didn’t know Rip was funny.’ Bette Midler said [here he begins to imitate Midler], ‘I didn’t know Rip was funny. Did you know Rip was funny? Well I didn’t know he was funny.’ They had me pigeonholed as a guy who could kick people in the head and do it convincingly. Years ago, when I was working with Burl Ives in New York in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof we’d go over to his apartment for beer and barbecue, and he’d tell me, ‘Let the other guys do the crybaby stuff. Go for the laughs.’ ”

Since the sun is over the yardarm and we’re both technically off work, we share a drink of twelve-year-old Scotch while Rip opens his mail. One letter is from a woman he hasn’t heard from in three years. “She must have heard about my Emmy nomination or the CableACE award,” he says with a chuckle. “I can just hear her now. ‘Oh, shit! I didn’t know he was a comer. I thought he was a goner.’ ”

A belly laugh that seems to come from the bowels of the San Andreas Fault shakes the room.

Rip owns a three-acre farm in Connecticut and a brownstone in New York, just north of Greenwich Village, but when he’s filming on the West Coast, he lives alone on the beach in Malibu in a rented cottage not much larger than a bait shack—and about as well furnished. An unmade bed dominates the main room, where there is also a chair, a table covered with papers and clothes and books, and a bookcase crowded to overflowing. The bathroom is no wider than a broom closet, and the kitchen is just large enough for one person to turn around. A rickety balcony overlooks the ocean, which at high tide pounds the pilings beneath the cottage. Pots of herbs and flowering plants occupy every spare space of its exterior, and vines of tomatoes and squash crawl up the walls and disappear over the roof. Rip studied agronomy at Texas A&M, the same as his father, and grows things wherever he happens to be. There are even small pots of germinating seeds in his dressing room. “He actually grew corn on the roof of his townhouse in New York,” Rip’s aunt, Rose Spacek Byrd, told me. “My husband swore it couldn’t be done, but Rip did it. He inherited a green thumb from Granny Spacek. ”

Rip is extremely close to and protective of his family, which is large and scattered from Connecticut to Texas to Los Angeles. When he is not on the West Coast, Rip spends most of his time in Connecticut, tending his garden and indulging his passion for hunting and fishing. At age 63, he prefers to live alone and socializes infrequently. Rip has six children by two wives and a mistress, and two grandchildren. His children range from 2 to 38 in age. The eldest, Danae Torn (born to Rip’s first wife, actress Ann Wedgeworth), lives in L.A. and is an actress herself. Three children were born during his long marriage to the late great actress Geraldine Page—Angelica, who has two children of her own, and the twins, Anthony and Jonathan. All three are actors and sometime writers and directors, and live together in the brownstone, where Rip keeps a basement room for himself. Rip also has two young daughters by actress Amy Wright, who divides her time between her own apartment in New York and the farm in Connecticut, in which she owns a half interest. Rip sees or talks to his children almost daily. “Every Christmas they all gather in Connecticut or New York, and Rip cooks the goose,” says his younger sister, Pat Torn Alexander, who lives in Fort Worth. Though their mother, Thelma, died last December, Rip and his sister talk about her constantly. Indeed, Rip speaks of his parents so frequently, and with such tenderness and presence, that I keep forgetting that both have died. Thelma lived to see her son’s success in The Larry Sanders Show, though she was never comfortable with the show’s frequent use of profanity.

Rip’s real name is Elmore Torn, the same as his father. Both father and son were called Rip, as are an uncle and a cousin. “If your last name is Torn and you go to Texas A&M, they call you Rip,” says Pat Alexander. The original Rip was the longtime agricultural director of the East Texas Chamber of Commerce, a man of great energy and vision who introduced the black-eyed pea to farmers all over the world. One of his proudest accomplishments was the establishment of an agricultural experiment station in a leper colony in Vietnam—at the beginning of the war, while posing as a French priest with leprosy. “My dad told me, ‘Take a stab at acting. Otherwise, you’ll never be happy doing anything else,’ ” Rip recalls. Even today, twenty-three years after his father’s death, Rip still hears that old familiar voice speaking to him in times of decision or difficulty or crisis. “I hear him sometimes, saying, ‘If you can just learn to control that temper of yours, if you will just learn to count to ten, you’ll accomplish a great deal.’ And I try, but my temper is like a mineral dropped in my blood, something beyond control. So I’ve learned to just walk away from a situation. But I tell people, ‘When I walk away, don’t nobody follow me.’ ”

Rip believes that he is not appreciated in his home state, and this burns in his gut. Some of the best-known performers in Texas don’t even recognize that he’s one of them. “When I first met Willie Nelson on the set of Songwriter, he thought I was some dude from the East,” Rip says. “He was very cool toward me until he realized I grew up in Longview and graduated from high school in Taylor.” Nelson and Torn are now close friends. Despite his long career in the New York theater, Rip is thoroughly Texan. His paternal and maternal ancestors, the Torns and the Spaceks (actress Sissy Spacek is his cousin), came to Texas before the Civil War, some landing in Galveston and traveling by oxcart to the area around Fayetteville and LaGrange. When he first moved to New York in the mid-fifties, Rip used the name Elmore, partly because it suggested his Texas roots and partly because he liked to buck the trend, which in those days was to put cute handles like Rock and Tab on young leading men. These names had a homosexual connotation because there was a well-known homosexual agent whose clients included many gay actors with macho-sounding first names. “The name Rip was a hazard,” a writer and longtime friend of Torn’s told me. “The first time I heard of Rip Torn, I just assumed he was gay. ”

If it can be said that anyone is a born actor, then Rip Torn is a born actor. As a kid growing up in Longview, Rip demonstrated an irrepressible artistic impulse. He wrote stories and plays, which he performed for family and neighbors, and he sketched birds and other wildlife. Early on he sensed the appeal that he had for audiences and the pleasure and fulfillment that performing gave him. “My father did a lot of public speaking, and I watched him, the way he could crack a joke and be funny without being cruel,” Rip recalls. “My grandfather was a cotton buyer in Taylor, and we’d go downtown on Saturday and watch the people walk around, then I’d go home and practice imitating their walks.” In college in the early fifties, Rip joined the Aggie Players, a move that hooked him for good on an acting career. After two years at A&M, he transferred to the University of Texas, in Austin, and earned a degree in drama. After graduating from UT, Rip hung out for a few months with a Dallas theater group headed up by Baruch Lumet (father of director Sidney Lumet). Rip made an impression on Lumet. “When he heard I was going in the Army,” Rip says, “he told people, ‘Rip can’t be an officer in the Army, but he can play one.’ ”

After his military service, Torn decided to try his luck on the New York stage. If an actor wanted to learn and grow, Torn believed, he went to New York, not Hollywood. In the grand tradition of the American and European stage, Torn studied the fine points of his craft: posture, elocution, dance (under Martha Graham, among others), fencing, staging, lighting, wardrobe. And, of course, acting. He got his first paying job in 1955, when he was 24, as Ben Gazzara’s understudy in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. By then, Rip had a wife (Ann Wedgeworth, whom he had married in 1955) and baby to support on a salary of $150 a week. Four years later, he landed the role of Tom Junior in the original production of Sweet Bird of Youth, the Tennessee Williams hit that starred Paul Newman as Chance Wayne, the aging golden boy who hitches his future to the once beautiful but now fading and boozy Alexandra Del Lago, played by Geraldine Page. When the show went on the road, Newman left the cast for Hollywood, and Torn inherited the role of Chance. The intensity of Torn and Page in the starring roles electrified audiences. Their performances were almost a case of life imitating art: Torn was seven years younger than his far more famous costar. By 1960, Torn’s first marriage had ended, and he and Page were married. For a time, Torn and Page were one of the best-known couples on the New York stage. Their friends included Tennessee Williams and other playwrights and notables, and in 1963 they were invited to Hyannis Port by President and Mrs. Kennedy to discuss plans for starting a national theater. Kennedy’s assassination cut short those plans, but Torn and Page eventually founded the Sanctuary Theater Workshop, a refuge in Greenwich Village where actors were able to spend time between commercial jobs. Throughout the seventies, they lived in their New York brownstone and performed on Broadway and in smaller Off-Broadway theaters like the Sheridan Square Playhouse and Circle in the Square.

Along with a group of radicals, rockers, and left-wing friends, Torn took part in civil rights marches and other liberal causes in the sixties, none of which helped his career. Rip believes that his career was damaged by an unofficial blacklisting as a result of these activities. Though this may be true, I couldn’t find a producer or director who recalled Torn’s name on a blacklist; the list that stifled the careers of talents like Dalton Trumbo and John Henry Faulk was a few years before Rip’s time. Nevertheless, when I visited Rip at his cottage in Malibu, he insisted on giving me a folder of documents that included a government memorandum listing Rip among a group of “prominent Negroes” who accompanied the writer James Baldwin to a meeting with Attorney General Robert Kennedy to impress upon the administration the sense of anger and deepening alienation among blacks in America. “That memo listing me among the prominent Negroes says a lot about the intelligence apparatus of this country,” Rip snorts with satisfaction. The folder also included Rip’s Army discharge papers and other documents substantiating his military service. I still don’t understand why Rip wanted me to have this material, but his civil rights activities and his military service are obviously defining moments in his life, pursuits he is enormously proud of and about which he is more than a trifle defensive.

Some of Torn’s oldest friends believe that his marriage to Geraldine Page hurt rather than helped his career. “When you are around a star of that magnitude, there are no rules,” one of them told me. “It’s pure heat.” Page’s manager openly snubbed Rip on several public occasions. Rip acknowledges that the marriage didn’t always work to his advantage. “When I married Gerry, I was considered one of the five or six best actors in New York,” he says. “Suddenly, it was like I’d never done a thing. People would push me out of the way to get to Gerry, literally push me aside as though I weren’t there. After a while, I started getting physical. I would run my boot down their shinbone, which had a most electrifying effect.” In the seventies, while others from his group at the Actors Studio were migrating to Hollywood and the movies, Rip stubbornly maintained his ties with the theater, partly because he believed that was what an actor did, but also because Page refused to leave New York. Rip played television roles, like his wonderful portrayal of Walt Whitman in the CBS production of Song of Myself, and acted in occasional films, such as Tropic of Cancer and Payday—each of which was supposed to launch his film career but didn’t, because the movies were financial busts.

Rip’s reputation for being difficult accelerated with a story in the New York Times Magazine, later picked up by the Village Voice, that said he had walked off the set of Easy Rider. The story wasn’t true. Rip had never been on the set of Easy Rider. The role of the square, small-town attorney had been written for Rip by his friend Terry Southern. But Rip turned it down because of money: Producer Peter Fonda wanted to pay him the Actors’ Guild minimum of $2,400 for four weeks’ work, rather than the $3,500 that Rip needed to prevent the IRS from placing a lien on his bank account. Instead of doing the Academy award–winning film that launched the careers of Fonda, Jack Nicholson (who won an Oscar for the role of the small-town attorney), and Dennis Hopper—and virtually defined the seventies—Rip took a part in Norman Mailer’s doomed production of Maidstone. This project ended with a genuine on-camera fight in which Torn bashed Mailer on the head with a hammer and Mailer nearly bit off Torn’s earlobe. The fight was mostly Mailer’s doing: as producer-director of the film, Mailer had insisted that the cast improvise a surprise “assassination attempt” on the character he played. Rip’s mistake was making it a little too real. Because of his reputation Torn was seldom offered major roles in major productions, even though almost everyone recognized his enormous talent. “Get me a Rip Torn type,” producer Marty Ransohoff told Terry Southern when they were casting the role of the devious gambler in The Cincinnati Kid. Southern was able to convince the producer to use the real Rip Torn, but such victories were few and far between.

“I had a family to support, so I found work anywhere I could get it,” Rip remembers. He worked in Off- (and Off-Off-) Broadway productions and occasionally did summer stock with Page. Critics praised Rip with phrases like “a virtuoso’s performance by one of the best American actors.” In the late seventies New York Post critic Martin Gottfried wrote: “Torn strikes me as a working actor, not a maverick; a superb actor who can’t and won’t do anything else, and why should he when he knows he’s superb?” But outside of New York, Torn’s work went largely unknown and unappreciated.

Though Torn and Page remained married for 27 years, they lived apart from about 1978, when Rip decided to move to Los Angeles and concentrate on film work, until her death in 1987. Rip dated other actresses (and a few non-actresses), but he was always at Page’s side at important show business functions, like the 1985 Academy awards when she won an Oscar for her role in The Trip to Bountiful. Page was the love of Rip Torn’s life, though not necessarily the passion. Rip’s passion has always been reserved for acting.

Rip’s reputation as a troublemaker has been greatly exaggerated, often by Rip himself. And though his fierce intensity no doubt scares some directors, many of the stories of his behind-the-scenes antics are warped by the film world’s strange view of reality. For example, on the Tonight show recently, Dennis Hopper, who directed Easy Rider, complained that the reason he doesn’t like to work with Rip Torn is that Rip once pulled a knife on him. Rip remembers that it was Hopper who pulled the knife—a steak knife, as it happened. The confrontation took place at a restaurant on New York’s Upper East Side when Hopper interrupted Rip’s steak dinner with a wild story about a scouting trip for Easy Rider. Terry Southern and others who were there support Rip’s version. “Dennis said something derogatory about the state of Texas,” recalls writer Don Carpenter, who later used this scene in his movie Payday. “Rip began to growl into his steak, and suddenly Dennis is waving a steak knife in Rip’s face. I don’t think Dennis even realized what he was doing until Rip reached up and took the knife away from him. Dennis flailed backward and knocked Peter Fonda off his chair.” (Confusing stage blood with the real thing is a common flaw among people who get paid to make-believe. At a New Year’s Eve party one time in Mexico, I watched an old character actor, angered by some insult, smash a whiskey bottle across a bar, as he had no doubt done in many western movies, and in the process cut off his thumb.)

This is not to say that Rip Torn can’t be a handful. Theater critic Robert Brustein, who was the artistic director for a production of August Strindberg’s The Father at the Yale Repertory Theatre in the seventies, remembers Rip as “one of the most intense human beings any of us had ever met . . . We never knew when he was going to interrupt rehearsals over some apparently insignificant provocation like a lost prop or a missing costume element.” Rip refused to walk onstage for the final rehearsal until an antique rifle had been replaced with a flintlock. To Rip’s way of thinking, this was an elementary request. He had done his own translation of the original Strindberg play and believed that a retired military man on a small pension would have sold the antique and replaced it with a common flintlock. Even after the offending rifle had been replaced, Rip walked through his entire part making no attempt to act it, using the time instead to examine props, inspect costumes, and glare at the other actors. “On the evening of the preview,” wrote Brustein, “I learned the reason for this curious behavior. Torn had been getting used to the room, turning his costume into clothes, making the props his own possessions. That night he proceeded to give a performance that was so riveting in its realism, so honest and terrifying, that we feared he might do serious harm to Elsbieta Chezevska, playing Laura, his malevolent wife.”

The Polish-born Chezevska was a mass of bruises afterward, but so was Torn. “That’s the way Strindberg wrote the damn play,” Rip tells me. “They brutalize each other. He left bruises on her; she left bruises on him. I actually thought at one point about picking her up and throwing her into the audience.” Brustein recalls that Rip treated the actress offstage with the same “cruel contempt” that he showed her in the play. By contrast, he couldn’t have been sweeter or more solicitous to Meryl Streep, who played his beloved daughter, Bertha. When Brustein suggested that the overworked Streep let her understudy take over for one performance, she told him that Rip would never stand for it. “He really thinks I am his daughter,” Streep said. “If anyone else went on in my place, even if you told him about it beforehand, he would stop the show immediately and say, ‘Where’s Bertha?’ ”

Rip’s fidelity to authenticity can boggle the mind. Before appearing in a production of Macbeth at UT, he had himself locked inside an insane asylum. It can also save an otherwise bloodless production. In a memorable scene in Heartland, Rip put his Aggie training to use by helping a heifer deliver a calf, a moment so compelling that the producer changed the film’s ending to accommodate it. Before his Oscar-nominated performance in Cross Creek, Rip not only took fiddle lessons but insisted on building his own swamp boat, over the strong objection of his producer. “I thought he was gonna fire me,” Torn recalls. “I remember hearing my dad’s voice saying, ‘You got a lot of money in the bank, do you, boy? Jobs that easy to find?’ ” But authentic props are the tools of the trade, Rip believes. “If you have the right tools, the right props, the right dress,” he says, “and if the script is good, you have to be a damn rotten actor to screw up.” Rip is even offended by shortcuts in other people’s movies. After watching The Deer Hunter, he complained, “That’s not a deer; it’s an elk.” And though he enjoyed In the Heat of the Night, he was annoyed to detect the song of a California valley quail in a scene that was supposed to be set in rural Georgia.

Robert Brustein believes that Torn’s training at the Actors Studio has, in the long run, been a negative influence on his career. “Rip is certainly one of the most powerful, innovative actors in this country—he has a range equal to any of the great English actors’, ” Brustein tells me. “I once saw him improvise Nixon as Richard III, and it was an absolute classic. But with Rip, everything has to be on stage as it is in life. That insistence on absolute truth has harmed his career. ”

On the screen as well as the stage, Rip’s range is astonishing, as is his list of credits, which covers more than a full page in a directory of contemporary theater and film performers. He has played an extraordinary array of characterizations and age spans: snarling psychopaths, loutish politicians, swamp rats, fry cooks, presidents, Texas Rangers, Danish artillery captains, Scottish farmers. And like a handful of other great actors (such as De Niro and Duvall), he has the power to make an audience forget that the man on the screen is an actor named Rip Torn.

Maybe because he has never openly aspired to stardom, there is a perception that Rip Torn lacks “star quality”—an ephemeral phrase that has little to do with acting. Chuck Norris has star quality. “Some actors are just fascinating to watch,” says Bill Wittliff, who has been writing, directing, and producing motion pictures for at least twenty years. “In even the roughest, most repelling roles, something comes through that makes you watch. A classic example is Anthony Hopkins in Silence of the Lambs. Robert Duvall has it. Tommy Lee Jones has it. Rip Torn has it.” Don Siegel, who directed Rip in Jinxed!, has said, “Rip was never the kind of guy who had star quality. He could act ten feet tall for you. He can do any accent, change his body, his look, his eyes, any of that—but none of that is star quality.” Rip naturally disagrees with Siegel’s assessment. “If Siegel means that I disappear into the character I play, I do. That’s deliberate. But anyone who thinks I don’t have star quality, let them explain why the eye goes to me. If I don’t have star quality, why do other actors constantly accuse me of stealing scenes? George C. Scott had me fired from a production of Desire Under the Elms because I got more applause than he did.”

I was unable to contact Mr. Scott to confirm this story. But I am willing to believe that Rip did get fired.

By the end of the week, when they are shooting the final segment of this episode of The Larry Sanders Show, Rip has managed to expand his part somewhat. He hasn’t exactly stolen scenes, but he has succeeded by wit and wile in persuading the producers to give him some extra time on camera. Rip settles back in the makeup chair and savors the irony. After forty years in the business, the role of Artie has made him an overnight success. Contrary to what the demons may have him believe, all of Rip’s longtime friends that I talked with—Norman Mailer, Terry Southern, Don Carpenter, Willie Nelson, and others—were delighted by the upturn in his career. “The great thing is not just that he has lasted so long,” Southern told me, “but that he has done it all without sacrificing his integrity.” And yet, despite it all, Rip still feels that perpetual lump in the pit of his stomach.

“I’ve spent most of my life as a gypsy,” he says. “This is probably the second time in my adult life—the first was when I was in the Army—that I’ve known job security. For forty years I’ve gone to work every day wondering if this was the day I’d be fired, and sometimes it was. But I’ve learned to pace myself, to take a nap after lunch instead of worrying about something. I’ve learned how to sustain a continuing role, and to keep from burning out. Also, things that would have got to me two or three years ago, I don’t stew about it anymore. I’ve come to grips with my demons.”

There is a gentle knock on the door and a timid voice calls out, “Mr. Torn, they’re ready for you, sir.”

“I’ll be with you in a second,” he says, a trace of a smile creasing his face before he realizes what has happened. It’s a momentary loss of concentration, nothing more. Then his eyes narrow, and he’s Rip Torn again.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- TM Classics

- Television

- Longreads

- Temple