BEING OF AN ADVENTUROUS, NOT TO SAY FOOLISH, spirit, I made arrangements to spend the night at San Antonio’s Menger Hotel in a room that is rarely available to guests. The reason it is rarely available to guests is that people, both sane and otherwise, believe the room is haunted. I decided to stay there with nothing but a fistful of cigars and a Gideon Bible. I have to confess that as darkness descended outside, a gnawing feeling of foreboding descended upon my soul. But it was, I figured, the only way I’d have a ghost of a chance of seeing a ghost. I must admit that I was fairly cynical about the whole operation. That’s probably the reason it wound up scaring the hell out of me.

Perhaps it was a blessing and a curse that the Menger Hotel was built upon the storied battlegrounds of the Alamo only 23 years after the fall of that bloody and beautiful cradle of Texas freedom. Be that as it may, since 1859 the Menger has been the home away from home to everybody from Robert E. Lee to Robert Mitchum to Robert Zimmerman. In 1976 I stayed at the Menger with Zimmerman, who is sometimes known as Bob Dylan, as part of his traveling musical circus, the Rolling Thunder Revue. Bob played his harmonica all night long, and when I finally got to sleep, I dreamed that I’d died and gone to heaven. I told Saint Peter that I wasn’t coming in unless he promised that Bob wouldn’t be there. He promised, I entered, and the next thing I heard was a familiar-sounding, whiny harmonica, which caused me to become highly agitato and accuse Saint Peter of welshing. Saint Peter, already mildly miffed by my presence, then intoned, “I’m telling you, hoss, that’s not Bob Dylan. That’s God. He just thinks He’s Bob Dylan.”

Be that as it may, a galaxy of other luminaries—from Oscar Wilde to John Wayne—has stayed at the Menger as well. Teddy Roosevelt organized the Rough Riders at the Menger Bar in 1898. It has been widely reported that on one fateful night Teddy’s monocle popped out and fell into his jug of Old Grand-Dad, which he promptly drank, monocle and all. It gave him some new insights into himself—eventually leading him to run for the presidency. In all, a grand total of thirteen presidents and future presidents have spent time at the Menger over the years, including Bill Clinton (who stopped by to sample the hotel’s famous mango ice cream), and Bush the Younger (who in those days may very likely have stopped by to sample a little of what made Teddy want to run for president).

But there have been other guests at the Menger who are sometimes not as celebrated. They make spontaneous appearances never bothering to call ahead for reservations and seldom, if ever, staying the night. They arrive in the form of spirits from the near and distant past, and for want of a better term, they are widely regarded as some of the world’s best-documented, most-often-sighted, most highly discerning ghosts.

Probably the most reliable authority of these ghostly comings and goings is Ernesto L. Malacara, who’s been with the hotel for 24 years. Ernesto has fielded hundreds of reports about the apparitions and has been an eyewitness as well. Not long ago in the spacious Victorian lobby, Ernesto saw what he at first thought was a homeless woman. Upon closer inspection, he noticed that her lace-up leather shoes, high-collared dress, and John Denver glasses were not the sartorial choices of the day. When he asked if she was all right, she looked up with the strangest, most ice-blue eyes and told him she was fine. He then walked about five steps away, turned around, and of course, she was gone.

There are two rooms in the Menger into which some maids will enter only in pairs, like animals at Noah’s ark, because of recurrent ghostly activity. There have been a number of sightings of Captain Richard King, the founder of the King Ranch, who liked the hotel so much he died there in 1885. The front desk occasionally receives late-night inquiries from guests regarding a maid wearing a lace apron who ignores them. The desk always tells the guests the same thing: “Maids haven’t worn those lace uniforms in eighty years.”

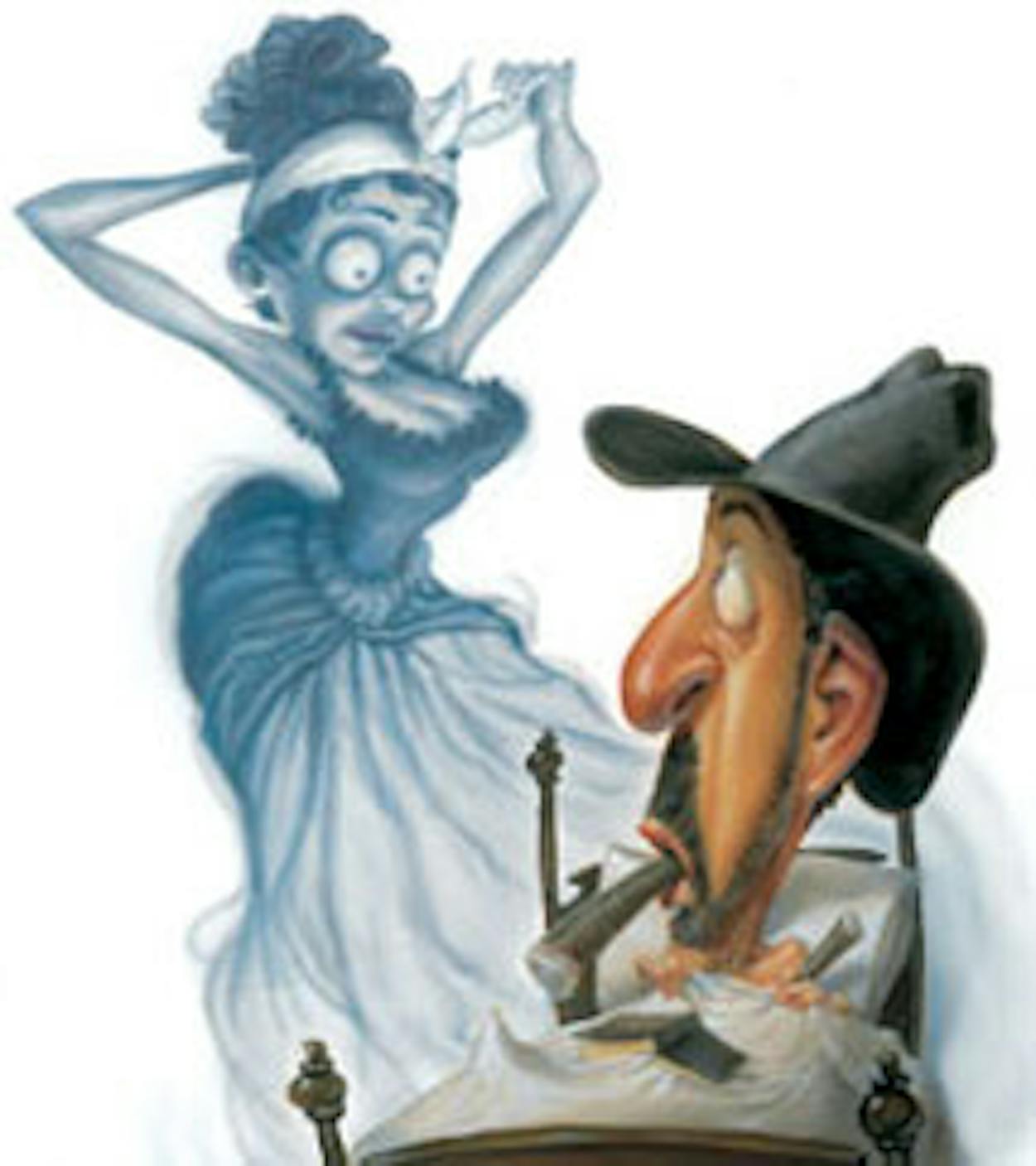

Maybe it was the combination of Old Grand-Dad and mango ice cream, but I woke up from a little power nap at three-seventeen in the morning and knew that something was wrong. A beautiful young woman with a bandanna around her head was floating at the foot of my bed. She did not look like Willie Nelson, and I knew it wasn’t a dream. I sat bolt upright and shook my head vigorously in a vain effort to will the vision away. She began swaying slightly and motioning at me with her hands and her dark, flashing eyes. It was definitely time to leap sideways. After I hopped out of bed, I followed her across the room, where, after a two-and-a-half-minute eternity, she floated into the wall and disappeared.

At dawn I called Ernesto. “That’s our Sallie,” he told me cheerfully. “Our Sallie?” I asked. “She’s probably our most frequently sighted ghost,” he explained. “Sallie White was a pretty mulatto chambermaid at the hotel. She often tied her hair back with a bandanna.” This made me a little nervous in the service; I had not told Ernesto that fact. “And she was shot by her jealous husband,” he said, “on March 28, 1876.”

Maybe it was just wishful thinking, but the flickering images of Sallie White seemed to remind me of an old flame. Her name was Jo Thompson, and she was Miss Texas in 1987. The two of us had had a good deal in common, of course, since I was Miss Texas in 1967. Nevertheless, there were striking similarities between the unforgettably radiant young countenances of Jo and Sallie. Everyone sees what they want to see, I suppose. I miss Miss Texas. I’ve often wondered what might have happened to the two of us if the world hadn’t gotten in the way. But what are ghosts after all if not the spirits of those we have loved and those we have lost and, just possibly, those we have left to discover?