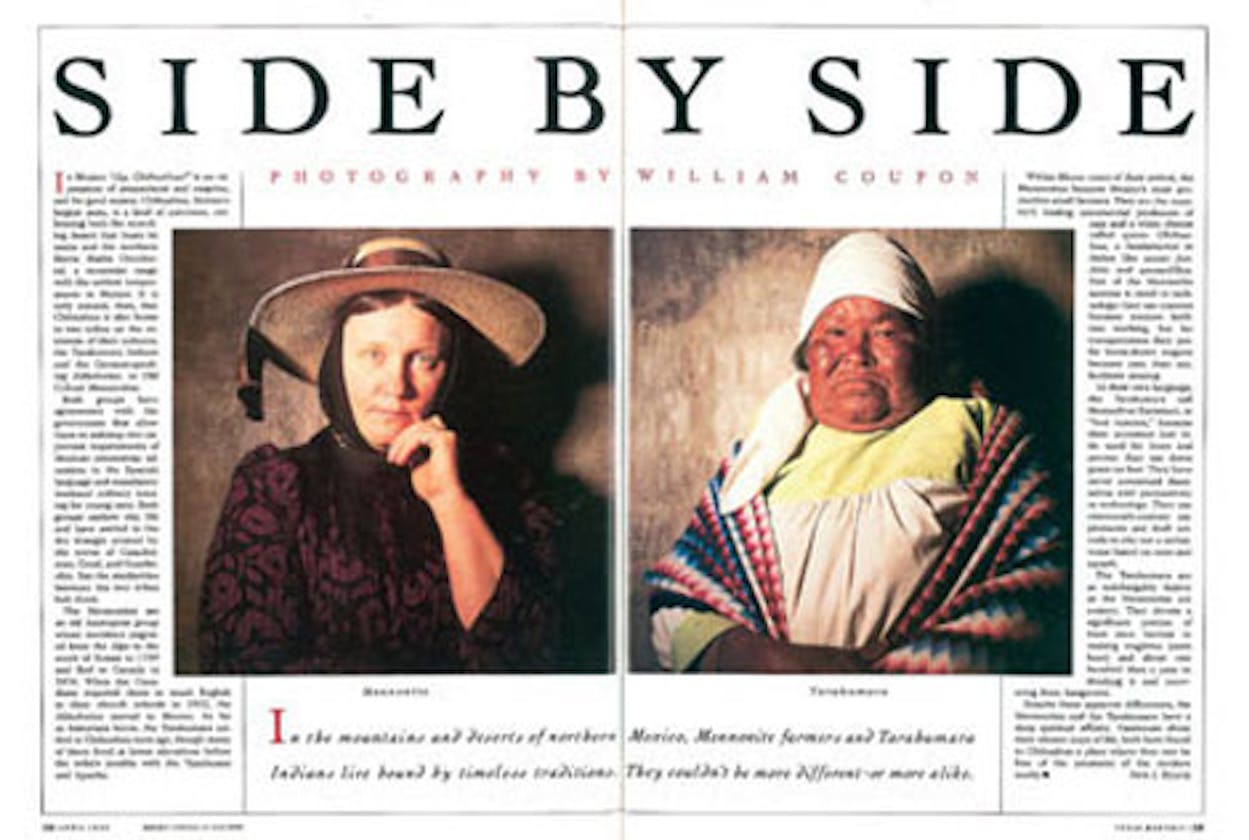

In Mexico “¡Ay, Chihuahua!” is an expression of amazement and surprise, and for good reason. Chihuahua, Mexico’s largest state, is a land of extremes, embracing both the scorching desert that bears its name and the northern Sierra Madre Occidental, a mountain range with the coldest temperatures in Mexico. It is only natural, then, that Chihuahua is also home to two tribes on the extremes of their cultures, the Tarahumara Indians and the German-speaking Altkolonier, or Old Colony Mennonites.

Both groups have agreements with the government that allow them to sidestep two important requirements of Mexican citizenship: education in the Spanish language and mandatory weekend military training for young men. Both groups eschew city life and have settled in the dry triangle created by the towns of Cuauhtémoc, Creel, and Guachóchic. But the similarities between the two tribes halt there.

The Mennonites are an old Anabaptist group whose members migrated from the Alps to the south of Russia in 1789 and fled to Canada in 1874. When the Canadians required them to teach English in their church schools in 1922, the Altkolonier moved to Mexico. As far as historians know, the Tarahumara settled in Chihuahua eons ago, though many of them lived at lower elevations before the tribe’s trouble with the Tepehuane and Apache.

Within fifteen years of their arrival, the Mennonites became Mexico’s most productive small farmers. They are the country’s leading commercial producers of oats and a white cheese called queso Chihuahua, a fundamental in dishes like queso fundido and quesadillas. Part of the Mennonite success is owed to technology; they use tractors because tractors facilitate working, but for transportation they prefer horse-drawn wagons because cars, they say, facilitate sinning.

In their own language, the Tarahumara call themselves Rarámuri, or “foot runners,” because their ancestors had little need for bows and arrows: they ran down game on foot. They have never concerned themselves with productivity or technology. They use nineteenth-century implements and draft animals to eke out a subsistence based on corn and squash.

The Tarahumara are as indefatigably festive as the Mennonites are austere. They devote a significant portion of their corn harvest to making tesgüino (corn beer) and about one hundred days a year to drinking it and recovering from hangovers.

Despite these apparent differences, the Mennonites and the Tarahumara have a deep spiritual affinity. Passionate about their chosen ways of life, both have found in Chihuahua a place where they can be free of the pressures of the modern world.

- More About:

- Mexico