It took my sister and me just two hours to demolish my dad’s train set. My mother went off to see him at the nursing home, and Julie and I got to work on the attic room. What else did we have to do, waiting for our father to finally die?

He’d been dying for a while, losing pieces of his essential self to Parkinson’s, first the physical, then the mental. Dementia—F. William Nelson had left the building. He wasn’t the man we’d grown up with, and that made it easier to accept his final passing. We’d become accustomed to his disappearing, to finding less and less of him there when we visited. He’d already moved out of the house, never to return, so dismantling his train set didn’t seem like a violation.

It had once been an elaborate affair, consuming a great deal of basement real estate, two or three different lines running at different strata around the room, backdrops made of plywood and painted to resemble mountains, a city of plastic buildings, populated by tiny people—laundry ladies, rake-bearing farmers, children at a bus stop—around whom the trains would swoop, synchronized and stylish, lit up and puffing smoke. There was a line from the thirties, one from the forties, one from the fifties, and my father their conductor, a man who’d also moved through those decades, always abreast of the current trends, always, in fact, ahead of those trends.

But over the years, as his mind grew messier, the train set also grew dissipated and odd. It moved to the attic, the backdrops fell away, the little buildings got broken, the three levels were reduced to one. Eventually, all he really did was connect pieces of track and work endlessly to make a single car move. “Fine motor skills,” he would tell you if you asked what was going on.

It was a hobby he would have been appalled to see himself take up. My husband taught me to make peace with my father’s decline by imagining what, at my age, he would have made of his current self. What would that forty-something-year-old have done with this eightysomething-year-old? What would the agile, active English professor think of the hunched, stiff form in the La-Z-Boy? What would he say about the model trains?

He’d had other hobbies that were more glamorous: French cooking, brewing beer in the basement, tying wild flies to accessorize his trout fishing passion, raising exotic fish, taking arty photos of my mother posed around the house in existentialist aspects (photos he developed in the lab he built in our second kitchen), making beautiful furniture—handmade cribs for each grandbaby. These we could get behind. They seemed a natural accompaniment to his eclectic and charismatic character. We could bring home our friends and brag.

But those trains. It was a hobby none of us could really understand. It disappointed us, frankly. Small children and Mister Rogers played with model trains! They had nothing to do with art or culture or dissent or anything even remotely cutting-edge. They were the male equivalent of the female sensibility given to running quaint B&B’s filled with doilies and dolls and useless embroidered pillows proclaiming needlepoint niceties.

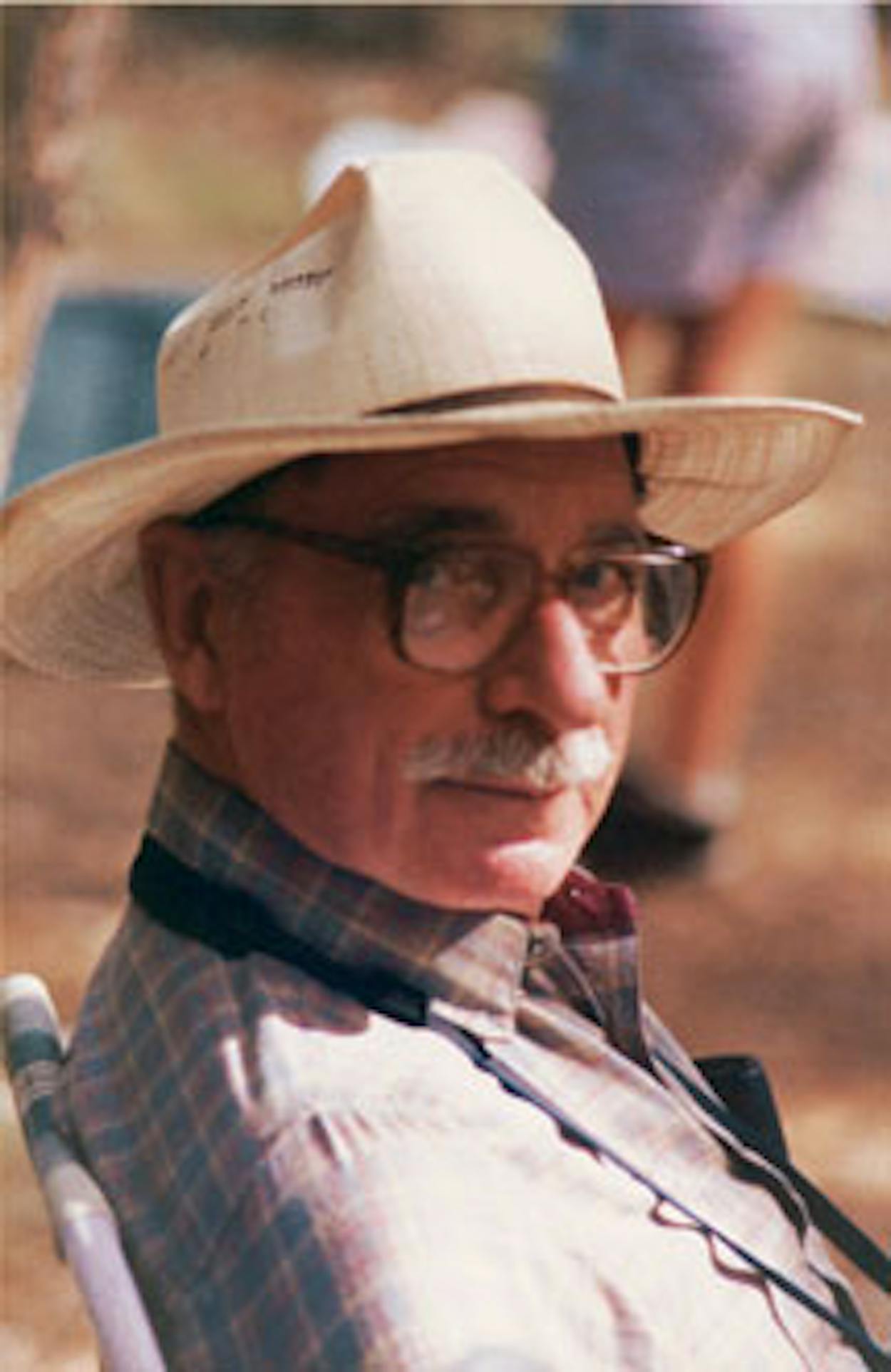

I suppose my father liked trains because he’d grown up in a time when they were one of the real options for travel. He certainly would have heard their lonesome whistles from any of the bedrooms he’d slept in as a boy and young man, that sound track to longing, to loneliness, to dreams of escape. He’d forever been afraid of flying and enjoyed seeing the world, especially the American West, from a train—usually the club car, cigar and martini in hand, lurid sunset in the distance. He covered a lot of ground—was raised during the Depression (and in the Dust Bowl, no less); served during World War II; went to college on the GI Bill; wrote one of the first master’s theses in the country on William Faulkner (this was at Columbia University, in New York, but he claimed that at that time there wasn’t a scholar on the faculty who knew enough about Faulkner to oversee the project); taught English for years and years at Wichita State University; hosted Allen Ginsberg in our home (where family lore says that I was, at age four, a rare youngster unafraid to sit on the bearish man’s lap); taught his grad students Joyce’s Ulysses at our dining room table; smoked pot on the porch; protested various wars at various peace rallies; began a film series and an honors program at the college; and took up all manner of culturally avant-garde positions. As children, we were denied white sugar. Our wheat-bread sandwiches were wrapped in wax paper because we opposed Baggies. Our peanut butter was organic, our jelly homemade, and our milk unpasteurized. We repaired rather than replaced. We knew who Adelle Davis was. We boycotted grapes and stopped for hitchhikers. We didn’t own a television. We were atheists. We believed war was unhealthy for children and other living things. We subscribed to the Evergreen Review, which wasn’t about trees. I mean to say, he seemed ahead of his time. In 2000, with most of his wits still about him, he purchased one of the first Toyota Priuses.

Is everybody’s father a larger-than-life character in the family narrative? His passions—natural history, literature, the environment, politics, justice, health, woodworking, house repair—determined all the important features of our lives. I had crap jeans because my father wouldn’t teach summer school—opting, instead, to go camping. We scrimped on material items and took pleasure in less tangible goods: space and time. We drove beaters because we prized our huge ramshackle house, which, by the way, was so cold during some winters that the mice I kept in my bedroom would literally go into hibernation.

“I hate those trains,” we all said when we came home to visit. But up we would go, to see him at the big sawhorse-supported table. With Q-tips and alcohol, he would be painstakingly cleaning the HO-scale track, hoping to make that car move a few inches without falling off. We paid our respects, shouted advice, glanced at our watches, waiting until we’d been polite enough to get back down to the kitchen, to happy hour, to real, life-size life.

The kitchen had once been his domain. There he would perch, alert in his captain’s chair, that tatty throne, reading the newspaper or Consumer Reports or whatever novel he was teaching, looking wryly over the top of his glasses, making witty, scathing remarks to the group of us who moved in and out of the room. It was the heart of the house, and he was its pulse. Whoever sat in his captain’s chair was aware of occupying a sacred spot. “Eighty-four hundred square feet of space,” he always grumbled, “and you all have to be in here.” Of course we did. Here was where he was.

“No frenzied bits,” he would warn us, his five troublemaking children, on Friday nights. He had a lot of adages, picked up from books and films and being raised an Okie. “No frenzied bits” meant not to wreck the family car or get arrested. When he finally died in the fall of 2005, I was prepared to have it inscribed on his gravestone. “He Rests With the Angels” or “Beloved Husband and Father” seemed so wrong.

My father was beloved, by a lot of people—his younger brothers, whom he raised up from their grubby Oklahoma origins into a fleet of urbane English professors; his wife, children, grandchildren; his innumerable students and friends. Parkinson’s stole a lot of his coherence, but he retained a gift for succinct phrasemaking. If you happened to have just come in from the cold and patted him on his head or cheek, he would recoil, hiss: “Feels like the touch of a sex-starved cobra!” At the bridge table he offered koan-like clues. “Might be Lottie,” he would obliquely utter, and then, as one of us, who, charged with leading, panicked at having forgotten what was trump—“Might be Squattie.” Huh?

After he died, we sat around the kitchen table and quoted him.

“Too much like kinfolk,” somebody said. That was how he had joked his way out of uncomfortably close encounters with us—too many people in a room or car, too much intimacy.

“Very filling,” someone else said, which was my father’s response to a meal that might have fallen a tad short of toothsome. “Very nutritious.”

“Don’t get so much mileage from your misconceptions.”

“It was good, what there was of it.”

“Better to remain silent and thought a fool than to open your mouth and remove all doubt.”

What I keep trying to reconcile is the image of that big man, with a big heart and a big brain and a big vision, being so involved with his little trains. Those silly miniatures. And their enthusiasts, whom we all had to go meet at the hobby shop or train expo as we accompanied my father there. Even the grandchildren grew bored with the model trains. They moved on: to music, to literature, to computers, to the culture booming around them. Their grandfather would have been proud, I told myself. Like my son, he’d be a fan of bands like Gorillaz, and he’d also be proud of Noah’s adoration of Miles Davis and Mozart. He’d be able to tell my daughter a thing or two about Cy Twombly or Donald Barthelme. He’d even approve of her lip ring, her shaved head, her thrift-store clothes.

Alas, by the end his passions had dwindled in number and in size. He loved his toy trains. He consorted with other HO-scale collectors. At Christmas, we gave him kits or cars, a giant authentic railroad crossing sign to hang in his attic room.

“Maybe we can sell this junk on eBay?” my sister said, over the pile of rubble.

“Doubtful.” It was dusty and broken. Handling the hundreds of pieces of track hurt the fingers. We stacked them in boxes and broke down the plywood. We combined the combustibles and the tools for future use, put the train cars to bed in their original packaging, separated the plastic props and businesses of the towns and their little occupants in a jumbled heap. We swept, then vacuumed. My mother returned from her visit to the nursing home, where the hospice workers were pulling their shift. She and I had written the obituary the evening before. She’s practical, efficient, ten years younger than my father but still a product of the Midwest, the frugal thirties, the generation that produced us boomers.

She was amazed at how little time it had taken us, her daughters, to completely transform the train room. Clean. A few days later, we would turn it into a bedroom. The bed my father died in would be transported from the home and installed up there. Now, visiting at Christmastime, that’s where I sleep. I thought I might have odd dreams, there where the trains once ran. My daughter sleeps in another attic room, full of the remnants of my father’s other hobbies. His bleached-out photos hang on the walls, and in boxes and on shelves are his feathers from fly tying, his bottle capper from the beer brewing, and his paperbacks, all the books he read of then-living authors.

I hung on to a cigar box full of little people, no bigger than my fingertip. They’d make good earrings, maybe. The woman shaking out a sheet. The guy with a shovel, cinders at his feet. Two children on a swing set, a boy and a girl, one flying backward, the other flying forward. A goose and her goslings. A coyote, sneaking along. An old man angled S-like in a seated position, designed to wait at a bus stop or train station, comfortable on a bench or chair, but now without anywhere to sit down.