Of all the trappings of my four years at the University of Texas, only one followed me to Dallas and appears destined to be with me the rest of my life: my sorority. Maligned and revered, the butt of jokes and jibes and the goal of countless anxious mothers for their daughters, sororities have kept their place in the rites of passage of a whole segment of Texas society that moves from summer camp to sorority to Junior League, with the same basic rituals serving at each level to strengthen the bond of women together. When I returned to Austin last fall to witness sorority rush, I had expected that the intervening years of the late sixties and the seventies would have changed things utterly. Instead, I found my memories going back to my own rush.

It was the fall of 1962, and I had just hobbled in ill-fitting stiletto-heeled shoes from the Chi Omega house on Wichita to the Tri Delt house on 27th Street in Austin. Word had not reached Texarkana that during rush week, regardless of the University policy which forbade freshmen to have cars, it was unseemly to walk from sorority house to sorority house. Socially astute and ambitious mothers from Houston and Dallas had willingly stranded themselves at the Villa Capri motel near campus, so that their daughters could drive the family car and arrive poised and oblivious to the beastly Austin September sun in their de rigueur dark cottons.

My dark cottons were severely circled under the armpits and the humidity made me regret the tight permanent wave that my mother had felt was necessary to keep my already naturally curly hair out of my eyes. The lengthy walk had made me late, and I half hoped that I could sit this one out. But before I could blot the sweat from my upper lip, a vivacious girl costumed like Judy Garland’s dog Toto pinned a huge nametag on me and led me down a cardboard yellow brick road into the cool interior of her sorority house.

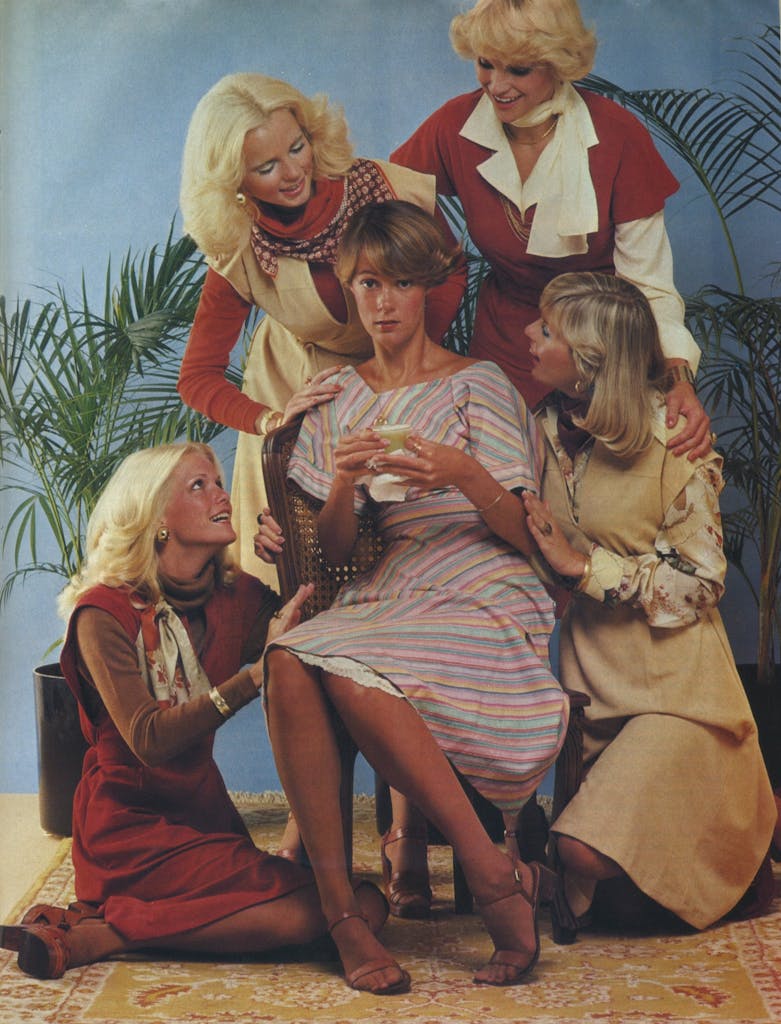

Like young Jay Gatsby, I had seldom been in such beautiful houses before. Although F. Scott Fitzgerald never mentioned Daisy’s sorority affiliation, these houses—particularly the Tri Delt and Pi Phi houses—could have been hers. Like Gatsby, I suspected that these houses held “ripe mystery . . . a hint of bedrooms upstairs more beautiful and cool than other bedrooms, of gay and radiant activities taking place through its corridors.” I was much too naive to recognize voices “full of money,” but I did marvel at the inexhaustible charm of these breathless beauties. I wrote to my parents after that first day of parties with Pi Phis, Tri Delts, Zetas, Chi Omegas, Kappas, and Thetas that I had never seen such a gathering of beautiful girls in my life. “High in a white palace, the king’s daughters, the golden girls”—in Pappagallo shoes.

Sororities at the University of Texas in 1962 were large by national standards. If all pledges remained active, a UT sorority could usually boast close to 350 active members. Even if only half of them were really beauties, the effect was overwhelming when you saw them—exquisitely groomed—in one large room.

After what seemed interminable non-conversation and punch which never really quenched one’s thirst, the lights dimmed at the Tri Delt house, and Toto gave me a quick squeeze, “You just sit right here on the front row. I’ll be back when the skit is over.” My naiveté once again kept me from being impressed by this privileged front-row position. Being squired around by a costumed sorority personality, I would later learn, also might indicate favoritism. The skits blur a little in my mind, but they were nothing less than major musical productions, often with professional lighting and costumes. We were the tail end of a generation raised on Broadway musicals and consequently were prime suckers for lyrics lifted from Carousel, Showboat, or South Pacific and altered for sorority purposes. I distinctly remember a green-eyed Tri Delt named Kay dressed as the carnival barker from Carousel sending shivers down my spine with “When you walk through a storm, hold your head up high . . .” It was that unflinching eye contact that got me every time, and by the end of the week, if you were a desirable rushee, someone might be squeezing your elbow by the time Kay’s voice reached the final “You’ll never walk aaalone.” Although the songs varied, that was the pitch at most of the houses. The girls locked arms around the room and swayed gently as they sang, all to remind you that it was a big University and that joining these self-confident beauties meant not having to face it alone.

As I watched these sorority girls flash their perfect teeth and sing and dance, I surmised that they possessed secrets that they might share if I managed to get out of the foyer and into those upstairs rooms. They not only knew their way to class on the 150 acres that then composed the University, but they also knew appropriate retorts when drunk Kappa Sigs pulled their skirts up at parties and howled, “Look at the wheels on this woman!” I knew they could hold their beer and their cool when someone “dropped trou” or toga at a Fiji Island party. I was sure that they did not worry—as I did—about where one slept when one accepted an OU-Texas date to Dallas or when one made the bacchanalian pilgrimage to Laredo for George Washington’s Birthday.

But the week was not all costumed escorts, squeezes, and front-row seats. Sometimes the carefully concealed rushing machinery broke down and the party lost its air of graciousness. A survivor recalls that in the grand finale of the Carousel skit, performers tossed bags of popcorn to prize rushees on the front row. One player overshot the front row, but remedied her error by wrenching the popcorn bag from the second-row innocent’s hand and restoring it to its intended mark. More often the embarrassing moments were brought on by a provincial rushee. It’s probably apocryphal, but the story floated around for years that, on being passed a silver tray of cigarettes, a rushee at the Zeta house looked puzzled for a moment, then reached furtively into her purse, emptied her cigarette pack on the tray, and quickly passed it on.

At the Pi Phi house I once held four “floaters” (sorority members who moved in and out of many circles at each party to get an overall picture of the rushees) captive with a fifteen-minute maudlin tale about the day my dog died when I was eleven. They feigned intense interest, their eyes brimming at appropriate times, but doubtless they collapsed in spasms of laughter and goose calls when I made my exit. The next day, to my horror, I was repeatedly introduced at the Pi Phi house with, “This is Prudence. Get her to tell you that neat story about her dog.”

But despite our faux pas, my roommates and I had an easy time of it. We were under no parental pressure to pledge at all. Totally ignorant of the machinations of rush, we innocently perceived the whole rush week scene as one exhausting and bewildering but happy experience in which we were to decide whom we liked best. We had only the vaguest notions about sorority rankings on campus. Although there were twenty sororities on the UT campus in 1962, for many girls, accepting a bid from other than the “big six” was apparently unthinkable. We were aware of tears down the hall as first- and second-period “cuts” were made by the sororities, but we could not appreciate the pain of the “legacy” (the daughter of a sorority alum) whose mother responded to her daughter’s rejection with, “Pack your bags, honey, SMU has deferred rush.” Or the one who declared, “See, I told you you should have gone to Tech first”—where it was easier to make it into an elite sorority and then transfer to UT.

The third period of rush week consisted of two Saturday evening parties. It was tense, and girls on both sides were exhausted, Members had culled their rushee lists to approximately 100. Too many rushees at a final period party could scare top rushees away. (“There were ten Houston girls at that party; they won’t take us all.”) In 1962 rushees were required to wear “after-five” dresses to these parties. Members usually dressed in white or, in the case of the Kappas, in sepulchral black. Sidewalks were lined with hurricane lamps and the houses were candlelit. This was the party for sentimental tearjerkers. The Thetas were renowned for leaving no dry eyes. The Tri Delts put a string of pearls around your neck and instructed you to toss a wishing pearl in a shell fountain while an alumna with a haunting voice sang mysteriously from an upstairs window. The Kappas still croon in four-part harmony.

And when we tell you

How wonderful you are,

You’ll never believe it.

You’ll never believe it.

That girls so fine could ever be

united in fraternity

And they all wear the little golden key.

[descant: ah-ah-ah-ah]

And when you wear one,

And you’re certainly going to wear one.

[This is when the not so subtle elbow squeeze came.]

The proudest girl in this wide world you’ll be

You’ll never believe it.

You’ll never believe it.

That from this great wide world

We’ve chosen YOU.

[Really look ’em in the eye.]

After two such parties (a first and second preference), the rushees departed for Hogg Auditorium to sign preference cards, which would be sorted by computer. Needless to say, no one folded, spindled, or mutilated her card. Sorority members would be up in all-night final hash sessions to determine their top 50 choices. On Sunday afternoon, the computer would print out the results. Panhellenic representatives sat with boxes of alphabetized envelopes. For appearances’ sake, there was an envelope for every girl who had attended a final party, but some contained cards with the message, “You have received no sorority bid at this time. Please feel free to come by the Panhellenic office to register for open rush.” Amid the squealing and squeezing that went on as envelopes were ripped open, perhaps it was possible to run unnoticed from the room with such an envelope and back to a lonely dorm room for a bitter cry. We were among the shriekers and squeezers and we did not notice. My three roommates and I had received bids to the same sorority, and our course was set.

Although we were to become somewhat aberrant sorority members, we had unwittingly chosen our bridesmaids, the godmothers for our future children, and access to certain social circles. Others in our pledge class already had this social entree by virtue of their birth; numerous legacies recall hearing Kappa songs as lullabies. I remember being fascinated by a framed family tree that hung in the study hall of the Kappa house. The genealogy was illustrated by linking Kappa keys (the sorority symbol) indicating that all of the women in this family had been Kappas for four generations. I distinctly remember feeling sorry for these girls whose choices were made inevitable by long family tradition.

Still others had simply been born in the right neighborhoods and had distinguished themselves in the privileged big-city high schools—which then were Lamar (Houston), Alamo Heights (San Antonio), Highland Park (Dallas), and Arlington Heights (Fort Worth). Small-town sorority members might have already joined these elite circles at expensive summer camps. Only one of my new Kappa roommates had done any of these things. She was a product of Camp Mystic, had attended a boarding school, recognized prestige clothing labels, and generally knew her way around the social scene into which the other three of us had stumbled. She was appalled at our ignorance. We had blindly selected our sorority because we liked each other and because we agreed that the Kappas’ whole rush setup was pleasantly amateurish and not at all intimidating. Quite frankly, we felt like we might be able to help them out. In a small-town high school, where rivalry was not particularly fierce, one tended to get an inflated idea of one’s abilities and talents. In a competitive big-city high school, one might be a cheerleader or serve on the student council, but in a smaller pond like ours, it was entirely possible to be cheerleader, star in the senior play, editor of the school paper, and a member, and probably an officer, in every school organization and still do well scholastically.

When we expressed these reasons for pledging later in a rush evaluation questionnaire, our active “sisters,” knowing that our egos could obviously take it, were quick to inform us that our pledge class had been a tremendous disappointment.

There were other illusions destroyed that freshman year. Girls who had chastely sung of truth, beauty, and honor during rush and had even lectured our pledge class on ladylike behavior befitting a sorority member would be seen holding forth with sloshing beer cup atop the toilet seat in the powder room during a Sigma Chi match party, “Furthermore, remember, you can drink like a lady.”

But the scales would not really drop from our eyes until rush the following year. We had spent many summer hours rewriting and casting skits and painting new scenery, and though exhausted we looked forward to rush with the enthusiasm that only one who has not already endured it can possess. The business of UT rush was mind boggling. Every member was required to attend unless she was out of the country. On arrival in Austin the week before rush week, members were handed a schedule of workshop activities and a list of at least 300 names containing pertinent information about each rushee. Hours and hours were spent in the basement with a slide projector flashing pictures of rushees on a screen while we shouted names, hometowns, and other key information. I was totally unprepared for the power blocs from the big cities. Houston might send twenty highly recommended girls through our rush, but the actives from Houston already knew which ones were to be eliminated before the end of the week. Gradually, as the pictures became more familiar on the screen during workshop, someone would shout out in the darkened room, “Gotta get that girl!” or “Key to Houston—get her, we get ’em all” or “Theta legacy-Theta pledge, forget her.” As the sessions got longer, girls became giddy and pictures of less than beautiful girls would be greeted with uncharitable mooing. I learned to become exceedingly wary of those air-brushed Gittings portraits of girls in their Hockaday graduation gowns.

Besides giving us some sight recognition of the rushees, I think “the flicks,” as we called the grueling picture sessions in the basement, served another purpose. When combined with song memorizing, skit practices, loss of sleep, and evangelical exhortations to “fire up!” they produced a certain singlemindedness that would enable almost-grown women to revert to what in retrospect seems incredibly childish behavior. Happenings in the outside world had no bearing on our lives that week. What really mattered was stealing Houston’s adorable Jo Frances Tyng away from the Pi Phis. By the end of rush week, when all but the die-hards had conceded loss, we dubbed her “Ring-ching-Tyng” (as in “Ring-Ching Pi Beta Phi,” a song sung to the jingle of gold charm bracelets at the Pi Phi house).

“Silence rules” prescribed by Panhellenic to prevent undue pressure on any rushee only contributed to the unreality of the whole experience. From the time they arrived in Austin until the end of rush week, rushees could associate only with other rushees. They could not have dates or talk to their parents. Sorority members were isolated in their respective houses with all telephones disconnected except one. Such isolation on both sides set the scene for considerable emotional buildup, hence the tears by third-period party, which were variously interpreted as “she loves us—we’ve got her” or “she loves us, but her mother was a Zeta and called her, crying.” In retrospect, I think all the tears were small nervous breakdowns.

When rush week began that year, we poured through the front door clapping and yelling, “I’m a Kappa Gamma, awful glad I amma, a rootin-tootin’ K-K-G.” I remember being slightly embarrassed by the peculiar stares we received from nonparticipants passing by, but nevertheless I sought out my assigned rushee and did my best to “give her a good rush” (introduce her to as many people as I could). By the third party of the day, our mouths were so dry that we sometimes had trouble getting our lips down over our teeth when the perpetual rush smile was no longer required. I was chastised more than once by a rush captain who saw me monopolize a rushee by having some “meaningful conversation” with her away from the babbling crowds, thus spoiling her chances for maximum recognition in the cut session that night.

The language of rush week almost requires a special lexicon. After the first round of parties, I was bewildered by the basement voting sessions. The rush captain had to keep things moving and be sure that sufficient people were dropped from our list each night to keep subsequent parties from being overcrowded. Certain signals developed for expedience. Members in agreement with a favorable comment being made on a rushee would begin to snap their fingers. Widespread finger snapping meant the rushee had sufficient support and that discussion could be curtailed. I also encountered that wonderful euphemism, “the courtesy cut.” The rush captain carefully explained that we owed it to legacies to cut them after first-period parties if we did not intend to pledge them. “That way they can go another direction,” she reasoned with us. We never allowed ourselves to consider that other houses were cutting the girl that night because she was our legacy—leaving her no “direction” to go. To avoid gossipy invasions of a rushee’s past indiscretions, any doubts about a girl’s reputation were phrased, “I don’t believe she is Kappa material.” From a reasonably credible source, this phrase could utterly destroy the rushee’s chance—no further discussion needed. Another shorthand signal that either cut a rushee from the list or initiated a lengthy debate was, “Y’all, I just think she’d be happier elsewhere.” I remember one particularly stormy evening when this phrase was used on an active member’s sister.

It took me until the second year of rush to perceive the battle lines that inevitably were drawn within chapters during rush. We dubbed it “the flowers versus the flower pots.” One ludicrous evening the debate in the basement had gone hot and heavy over a girl who had outstanding recommendations, scholastic average, activity record, and family background. She simply wasn’t “beautiful, adorable, or precious.” Just as the fingers began to snap favorably, a member whom I recall as being particularly nonproductive except during rush, gained the floor and whined, as only Texas girls can, “But yew-all, would you ask your boyfriend to get her a date?” The strongest proponent of the girl rose to her feet and shouted, “We’ve got enough flowers in this chapter! What we need are some pots to put them in.” My sentiments were usually with the pots, the solid citizens who kept the chapter machinery rolling by doing the undesirable jobs, kept the grade-point average high, and generally provided the diversity and good humor that flowers who rose at 5:30 a.m. to begin teasing and spraying their hair so often lacked. Flowers, of course, performed the essential function of keeping the sorority’s reputation with fraternities high enough to insure a steady stream of eligible males in and out the front door.

Although alumnae money and time kept the sorority houses well furnished, alumnae pressure varied from house to house. During rush week only one alum adviser was allowed at voting sessions, but alumnae could attend the parties. Aside from the pressure they exerted in the cities as to who received recommendations, alums had little influence in our rush. This was not the case at other houses. Friends from other sororities say that they were constantly plagued with alumnae who could not resist offering unauthorized “oral bids” at their parties. The Thetas, in those days, were traditionally beset by alumnae, not only from Austin but also from Houston and Dallas. Making an impression on Mrs. Alum at a party might be just as important as being labeled “precious” by the entire Houston active contingent. One former rush captain recalled a very persistent alum who as a last resort threatened to keep all the active members from her hometown out of the Junior League if they didn’t see to it that a certain legacy was pledged. The girl was pledged, but regrettably her pledge pin was jerked before the year was out for swimming nude with a dozen boys at their fraternity house after curfew.

At the end of the week the final vote was taken. The final usually included about three-fourths flowers and one-fourth pots, with legacies who had survived the courtesy cut securely listed at the top. Other names could be shifted around in the last-minute voting session held after the tearful final preference party. This was the party where oral bids, strictly prohibited by Panhellenic, slipped out. Rushees hoping for some assurance or just overcome by emotion would weep and hug their active friends at the end of the party and say, “Oh, I just wish I could stay here forever.” Statements like these would cause an uproar in the downstairs sessions. A cynic would rise and say, “Yeah, she said the same thing to the Pi Phis an hour ago.” But a believer would respond, “Y’all, I know she has a Pi Phi mother and two active sisters, but she wants us … I know she does. We’ve got to move her up the list.” The computer had its final say, and by Sunday afternoon, since several sororities were fiercely competing for the same 50 girls, everyone’s list had been altered somewhat. New pledges were greeted once again with hugging and squealing and after a quick supper were lined up like so many prize cattle in an auction to be inspected by the ultimate judges—the fraternity men. One of my favorite flowerpots recalled it this way. “If you were a beauty, you were immediately asked for a date and taken out of the gruesome inspection line. Because we were arranged alphabetically, I got to stand next to someone named Taney, five-feet-two, curvy, giggly . . . well, precious. Ten minutes after we lined up, she was surrounded with guys elbowing and shoving to get closer. I was ignored unless someone needed to know Taney’s name. I vividly remember standing there, awkward and skinny, alternately wishing painful and exotic diseases on Taney and at the same time cursing my parents for spending all that money on my ‘intellectual development’ instead of taking me to a good plastic surgeon in Dallas. I felt a little guilty when cute little Taney was pregnant by December and had to depledge.”

Pledges were guaranteed a date every night during University registration week, thanks to the efforts of fraternity and sorority social chairmen who laboriously matched girl pledge class with boy pledge class and posted the lists at the respective houses. At least two of my “match” dates took one look at my name and were suddenly called away to their grandmothers’ funerals. It was just as well; I could never drink enough beer to get into the swing of fraternity parties anyway. Even after I became an active member, no one ever shared the secrets of the cool retort, and sure enough tears came to my eyes when a drunk Kappa Sig pulled my dress up in the middle of the dance floor. I often wonder if some of my contemporaries who married their fraternity boyfriends, and have since divorced, perhaps mistook three years of standing arm-in-arm with sloshing beer cups in front of blaring bands as real intimacy. Could it be that when the keg stopped flowing and the music quit playing, they found they hardly knew each other?

Within the sorority system, however, good friendships did develop. Perhaps we would have experienced the same bonding in a dorm or co-op; however, I doubt that I would have known 150 women on the University campus as well as I did these without such a formal structure.

My sorority sisters and I did serve at each other’s weddings, and my children do have a Kappa godmother. We still exchange the Christmas cards with the long notes attached. Although we were frequently stereotyped as “look-alike-think-alikes” by our critics, within a group of 150 girls there was inevitable diversity. These were the days when the Bored Martyrs (a notorious women’s drinking society) were witty girls who truly could have been Mortar Boards (an honor society) if they hadn’t become cynical so young. We also had our share of philosophy majors, musicians, artists whose rooms were boycotted by the maids and labeled fire hazards by the fire marshal, campus politicians, professional bridge players, and party girls who frequently majored in elementary education or jumped from college to college fleeing scholastic probation. Most were, of course, from wealthy families, and for me, who had attended a high school where only 15 per cent went to college, it was an education in how the other half lived. I’ll never forget my father’s first visit to the Kappa house. He stood in the foyer gazing at the lovely furnishings and curved stairway. “Honey,” he said, “why do you bother to come home?” The sorority parking lot was filled with the latest model automobiles; one sister drove a classy vintage Mercedes. When a fire damaged the Dallas Neiman-Marcus one fall, there was genuine distress over whether Christmas would come that year. Being a part of the Greek community in the early sixties was a way of feeling rooted in a big University and eventually rooted in the state. These were privileged little girls, and their daddies and some of their mothers were powerful people—University regents, renowned doctors, influential lawyers, judges, king makers, or politicians themselves. The young fraternity men we dated became lawyers, doctors, bankers, went into “investments” or joined their fathers’ successful businesses. In the course of an afternoon spent doing volunteer work in Parkland Hospital’s emergency room recently, I heard the names of three blind dates from my freshman year being paged as resident doctors. Texas Law Review banquets and Bar conventions are like homecomings where the men still greet the women with the standard fraternity embrace. Even after fourteen years, the wives, especially the Houston flowers, are still quite glamorous. Flowerpots are more scattered as they frequently pursued careers that took them out of the South. One writes from New York as an assistant editor of a magazine, “Remember, I may have been a late bloomer—but I bloomed!” Others have become artists, lawyers, biologists, or academicians at universities where sororities are once again on the upswing. “I was invited with five other faculty members to a sorority house recently for what I think we called apple-polishing night,” writes one who is now an English professor. “After dinner the girls sang to us. The four male profs looked delighted, but I couldn’t resist searching the crowd to discern the pots from the flowers.”

With such continuity of friendship, social education, and broad acquaintance across the state, I can hardly dismiss my sorority experience. However, by the time we reached our junior year in college, many of us had begun to sense that something was amiss. There were strong conflicts between belonging to a sorority and trying to pursue an education. Why did we volunteer our time to help the Phi Delts gather wood for the Aggie bonfire when I could have been with my English class buddies hearing Tom Wolfe and Truman Capote? I missed Igor Stravinsky’s visit to campus because I was the song leader at chapter dinner. In retrospect, the conflict was most apparent when the sorority pretended to serve academic purposes. The poet John Crowe Ransom joined us for dinner one evening, and the only sustained conversation we could handle was “How are your grandchildren?”

Even worse was the night William Sloane Coffin, the activist chaplain from Yale, came for dinner. If I led the chapter in singing “Kayappa, Kayappa, Kayappa, Gayamma, I am so hayuppy tha-ut I yamma . . .” that night I have thankfully blocked it from my memory. Coffin, of course, was already condemning the escalating war in Viet Nam and generally taking a few cracks at lifestyles like ours. We, who had spent the previous weekend parading around in initiation sheets and performing the solemn Victorian rituals required to initiate our pledges, were ill-equipped to defend ourselves. The chaplain so easily trapped us that we could hardly say no when he challenged us to follow him to the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) meeting he was scheduled to address when he left our house. Slipping our pearl-encrusted Kappa keys into our pockets, we followed him with great trepidation down the alley to the University Christian Church where the meeting was to be held. We had seen these humorless campus radicals on the Union steps. Some of us had given token support to slightly suspect University “Y” activities; others had at least signed the petition to integrate Roy’s Lounge on the Drag, but we had never sat in the midst of such a group, and we shivered that our opinion on the Gulf of Tonkin might be sought. Fortunately the SDS was much too taken with Coffin even to notice us, much less explore our ignorance.

Besides the educational conflicts, the sorority could also be indicted for providing a womblike environment in which one could avoid practically all contact with the unfamiliar or unknown. Many of my sorority sisters now freely admit that they never even knew how to get to the Main Library, nor did they ever darken the door of the Chuck Wagon in the Student Union where my roommates and I frequently drank dishwater-colored iced tea with foreign students or “rat-running” psychology lab instructors. This same narrow environment also kept the haves from developing much sensitivity for the have-nots. Sorority alumnae groups are generous philanthropists, but in college our philanthropy was usually limited to a Christmas party for blind children or an Easter egg hunt for the retarded. The only have-nots sorority girls encountered on a regular basis were the servants in the house. I often wondered how the cook felt when the KAs rode up on horseback and sent a small black boy to the door with “Old South Ball” invitations on a silver tray.

Perhaps the worst indictment of the sorority system, however, is the damage done to the self-esteem of many girls either by the selection process or the values that may predominate after pledging. The same friend who recalled the gruesome pledge line insists that flowerpots dwindled after my class graduated and the standards of beauty, money, and cheerleader rah-rah became entrenched. “It was an unhappy time for me,” she writes. “I wasn’t like the rest and yet I didn’t know what else to be. Half the time I hated myself for not being able to fill the sorority mold I had been raised to believe was what a girl should be; half the time I hated myself for even considering becoming like them. Ultimately I led a double life, holding minor service offices and doing those daring ‘radical’ things, like introducing motions to allow Jewish girls to go through our rush. Graduate school was my lifesaver. My experience there was so good that it tends to block out the mindlessness, the social superiority, and the hypocrisy of those undergraduate days. Looking back, I see my two years in the house as most men regard their Army duty—only mine was service to my family and their values instead of my country. It was such a waste of potential and time. My life goes so fast now, when I compare it with those hours spent on phone duty as a pledge at the sorority house.”

Shortly after our graduation in 1966, a very different generation appeared, provoking many changes at the University—the Drag vendors, the use of drugs, massive demonstrations against the war, the no-bra look, the pass-fail grading system, bicycles as an acceptable mode of transportation, beer in the Student Union, the lifting of curfews in women’s housing, and courses called “Women’s Studies.” The whole Greek system suddenly was viewed as an anachronism surely doomed to extinction. Indeed, the Panhellenic Council removed itself in 1967 as a recognized campus organization, hence no longer subject to University regulation or eligible to use University facilities. Some say this became necessary when the University discontinued supervision of student housing except that which it actually owned and operated. Sorority alums were not yet ready to abandon curfews and needed an independent body to govern such regulations. Others insist that sororities with racial and religious discriminatory clauses in their bylaws felt threatened. In truth most sororities had purged their charters of such clauses long before civil rights unrest became a reality on campus. Numbers going through rush dropped drastically then; several fraternities and sororities folded, and living space in sorority houses went begging as girls moved to apartments.

The hypocrisy of the “standards committee,” which served as a self-policing morals squad within most sororities, finally crumbled in many houses. In our day, the standards committee had served without much question. Headed by the sorority vice president and assisted by an alum adviser, the committee was usually composed of girls of good character who ideally were imbued with discretion and compassion for the weaker sisters in their midst. They were charged with preserving the sorority’s reputation, which occasionally involved admonishing, disciplining, or expelling those who strayed. One contemporary of mine recalled that “nymphomania” was the big scare word in standards committee. “Pledge an ugly girl, but for God’s sake, don’t let a nymphomaniac slip through!” The fact was most standards committee members were intimidated by candidly rebellious behavior, and those girls who openly marched to a different moral drummer often escaped unpunished. It was the poor timid soul who, after two cups of spiked punch, vomited in the stall next to the alum chaperone at the spring formal that got called on the carpet. Apparently when birth control pills and drugs became readily available in the late sixties, it became difficult in many houses to assemble enough straight arrows to form such a committee. Rebellion widened the gulf that already existed between sorority members and what they regarded as “interfering” alumnae. University curfews were lifted, but sorority girls were still required to be in their houses at 11:30 on weeknights. Repeated violations of the curfew threatened to expel even the officers in some of the sororities. Pappagallo shoes were being exchanged for bare feet and Army fatigues. Housemothers resigned, and alumnae wrung their hands.

So I went back to rush week in 1975. I had heard that the number of girls going through rush was rising again, but I was skeptical. I still expected to see a tired old dinosaur ready for the last rites—or a vastly revolutionized sorority system. I found neither. There I was again in the Tri Delts’ front yard wiping the sweat off my upper lip. Well, a few things had changed. Panhellenic no longer lobbies for dark cottons. Dallas and Houston rushees were classy in their cool summer dresses worn fashionably three inches below the knee with rope wedges and bangle bracelets. My counterparts—girls from Edinburg and Fort Stockton—were most often represented by polyester church dresses worn three inches above the knee with pumps. Nervous conversation was unchanged. “Sounds like a mob scene in there. I’m not sure I wanta go in . . .” “I didn’t even know she was an A Chi O, y’all, I hope I don’t get in trouble.” In the minutes before the doors burst open, there was much flopping of long hair behind ears and finally, nail biting. The yellow brick road was gone, but the gushing enthusiasm was unchanged. The rush captain, or maybe she was the president, looked like Margaux Hemingway. In fourteen years, the beauty standards had been upgraded. I wasn’t permitted inside the houses—not even my own sorority house (alum pressure is out)—but from the curb I spotted the same machinery still in motion. I overheard a frantic active begging another, “Please take my second girl; I’ve just got to give Sally a good rush.” I watched as they unselfconsciously clapped, squealed, or ran out for a second goodbye hug even though a Panhellenic representative had signaled the end of the party.

In talking with active members later, I was amazed to learn how little rush really had changed. The songs, the finger snapping, and even the language were essentially the same. “She’s the key to Houston” had become “She’s the ticket,” just as a much admired fraternity man had gone from “stud” to “stallion.” Fatigue and giddiness still prevailed in the late-night voting sessions with a few cynical seniors sometimes tossing panties in the air and yelling, “We really rushed her pants off!” Skits are no longer the major productions they once were, but the silence rules, the maudlin sentimentality, and the weeping are still an integral part of the rush week scene. I asked about the tears. “Aren’t girls just too sophisticated now for that sort of gimmickry?”

“Well,” the innocents replied, “they really are a lot smarter these days and they know if you’re not really sincere. But that last night, well, you just look around the room and know how glad you are to be a Kappa—well, it’s just like the last night at camp, you just can’t keep from crying.”

“But what about the changes?” I asked. I was relieved to learn that girls receiving no bids are now called by a Panhellenic representative to spare them the public humiliation of the old no-bid envelope. I was not surprised to learn that sorority pins are never worn on campus, since they were beginning to fade from the scene even while I was in school. “Dressing” to go on campus has returned. I doubt seriously if the gold earrings were ever abandoned even when revolutionary garb was in fashion. Jewish girls are no longer restricted to Jewish sororities, but I saw no Spanish surnames other than Valley aristocracy. Black sororities still exist and since 1967 have participated in Panhellenic activities with the white sororities.

But I also wanted to know whether the outside world had forced many changes on the sororities. “What impact has the women’s movement had on sororities?” I asked.

“Not much,” they shrugged. “Oh, almost everybody majors in business or communications or elementary education, but it’s not because they really want careers. They just know that they’ve got to get a job when they graduate.” I suppose I should have anticipated this response. The women’s liberation movement had begun with an intellectual appeal, but most Texas woman have been brought up to trust their charm more than their intellect.

“What about marriage? Do you still pass the lighted candle at chapter meetings while singing,

I found my ma-an.

He’s my Kappa ma-an.

He’s my sweetheart for evermore.

I’ll leave him never,

I’ll follow wherever he goes.”

“We still pass the candle, but it hardly ever gets blown out. Not many of us are getting married after graduation, but it’s not because we wouldn’t like to,” they giggled.

“What about no curfew?” I asked, recalling how many of my sisters had sustained injuries while sneaking out of the house. One of my contemporaries had actually broken a foot in a fall from the fire escape and had to be hauled back up through a window. She awakened the housemother with a lame story about falling down the carpeted stairway.

“Well, everybody is usually in by two a.m. and usually earlier on the weeknights,” they assured me. Their parents, I learned, pay an extra $50 per semester for a security guard to let the girls in and out at night.

There was so much more that I wanted to know, but they were eager to hear about my bygone era. “Oooooh, you were here when they had Ten Most Beautiful and Bluebonnet Belles and Round Up Revue.” I could tell from their curiosity that ’ they felt cheated.

Because I sensed that I had been talking to the straight-arrow public relations team of the sorority, I deliberately sought out one of the two acknowledged scholars within their membership, a law-school-bound Plan II student. Plan II (a liberal arts honors program), the college of humanities, and the college of natural sciences were poorly represented in the sorority houses I investigated. This young lady was indeed very bright, and I pressed her to justify her Greek affiliation.

“Plan II is really a tough academic program,” she said, “and I study so hard during the week that if someone didn’t plan some mindless social activity for me on the weekend, I’d probably crack. My friends who came here from the same private high school and didn’t pledge are beginning to drop out. They just can’t face four years of college without ever going to a big party.”

I had called her away from an SAE street dance. She freely admitted that none of her dates on the weekend were intellectual types. “I talk about Kant and Hegel all week. I don’t want any more on Saturday.” She doesn’t live in the house because she needs the silence of her own apartment to carry such an academic load. “I sometimes wish I’d pledged a fraternity,” she grinned, “They have such a good time, dropping by their fraternity houses to shoot a game of pool, play cards, or just shoot the breeze. We only go to our sorority houses for some organized meeting—never just for the fun of it.”

The Greek system died out on many campuses across the country during the late sixties. The president of UT’s Interfraternity Council, noting that pledge classes and houses are full again, says, “The Greek system is definitely thriving.” Of course the 5000 people who participated in rush last year are still quite a minority on a campus of more than 40,000, even more of a minority than in the sixties when the 5000 Greeks made up about a fifth of the campus population of 27,000. However, after several years during which rush was totally ignored by the Daily Texan, the irate September letters have begun to crop up again in the “Firing Line” letters column: “Only a moron would pay someone to impose rules upon them of the ‘don’t speak to boys during rush week’ variety.” “Big sisters and study buddies, indeed!” “They remind me of swine at auction.” “The Greek system is composed of people with Pat Boone/Ann Landers mentality who insist on segregating themselves socially, sexually, and racially.” “I often wanted to become friends with one of those beautiful chicks with the long, flowing hair, but most of them are such conceited social climbers that I just stay away from them.”

Sorority members continue to dominate certain campus activities, such as Student Union committees, simply because they are joiners and organizers by nature. The University Sweetheart is invariably a sorority girl principally because no one else is interested and because the Greeks have the organizational power to get out the vote.

Certainly, the intimidating size of the University of Texas student body and physical plant had something to do with the returning strength of the Greek system. As one Highland Park mother put it, “When these affluent high school kids around here visit the University, they visit the sorority and fraternity people. That is the University to them. Not to pledge is to step into an unfathomable void.” Another mother admitted that her daughter was not a particularly independent spirit. “If she’s going to be a follower, we’d just as soon she be in a group where she’ll at least keep up her appearance.”

The nostalgia craze is certainly another factor in sorority revival in the seventies. When I visited the campus briefly in the spring of 1976, I saw freshmen spending hours stuffing crepe paper in chicken-wire floats for the Round Up parade, a spectacular phenomenon discontinued during the sixties at UT. Sigma Chi Derby Day, with its sorority relays and “tug o’ war” over mud-pits, has reappeared, and Greek-sponsored dance marathons for charity have been held in Gregory Gym. Indeed the current self-described absurdist student body president and vice president, Jay Adkins and Skip Slyfield, make the absurdities of Greek life seem quite in tune with the times.

And perhaps it’s more than just nostalgia. Some have suggested that it’s a longing for tradition. You’re supposed to feel something for your alma mater, aren’t you? At the University of Texas, if you don’t “feel it” for the Longhorns and Darrell’s winning tradition, the Orange Tower, and the “Eyes,” you have little else to come back for. UT has no ivied halls or picturesque chapels and few legendary professors. Most students graduate by mail rather than attend the massive impersonal graduation ceremonies. There are no formal homecomings or reunions unless you “belonged” to something while you were there—the Texas Cowboys, the Friars, the Longhorn Band, or even a sorority or fraternity, each with its own rituals and traditions.

I suppose the wisest answer to the survival question came from another sorority sister of mine. “Well, why do girls still make their debut in Dallas?” she asked. “Because people long for exclusivity, because their parents want them to, because they are only nineteen years old and are not asking the same questions that we ask at thirty-two.”

I think she’s right. I was recently perusing a copy of the Kappa Key, my sorority’s national magazine that finds me no matter where I hide. An interview with a bright-eyed blonde coed caught my eye. She had been Miss Everything on her campus, and, when questioned about the value of being cheerleader, homecoming queen, and sorority president, she replied, “I don’t think it’s always nice to question the relevance of things that are fun.”

You can always wait to do that when you’re thirty-two.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Longreads

- Higher Education

- Fashion

- Austin