Dive deeply enough into this green business and you find yourself doing some pretty geeky stuff. For example, I recently spent an afternoon discussing phantom energy with a fellow named Andrew Bond at Current Energy, a green-products boutique in Dallas. I’d never heard of the concept, and Andrew, a pleasant young man, was polite enough to explain it in simple terms to a curious old guy.

Essentially, phantom energy is power that goes to waste when it continues to course through wiring even when an appliance is not in use—the electrical version of a leaky faucet. You can eliminate it by plugging your small devices into power strips that themselves can be turned off as needed. On a later visit to the store, I bought two with “hot” and “cold” switches at $50 a pop; anything especially sensitive that needs to reboot—say, a modem—can be left hot while other appliances are shut off. I also forked over $100 for a solar-powered battery charger for my cell phone and MP3 player; it’s not only an energy saver but also a convenience when traveling.

The experience made me consider the myriad little ways you can be green and also nibble away at your utility bills. Indeed, like recycling, it seems that cutting back on the dribs and drabs of energy waste is a good way to get one’s feet environmentally wet. My first baby step, in fact, came last December, when I noticed a crowd that had gathered in an aisle of Elliott’s Hardware in Dallas. The object of attention was a shipment of compact fluorescent lightbulbs (CFLs) that a salesman was handing out like snake oil. “They’re more expensive at purchase,” he said, “but they last up to ten times longer than your regular bulbs because they use a quarter of the energy.”

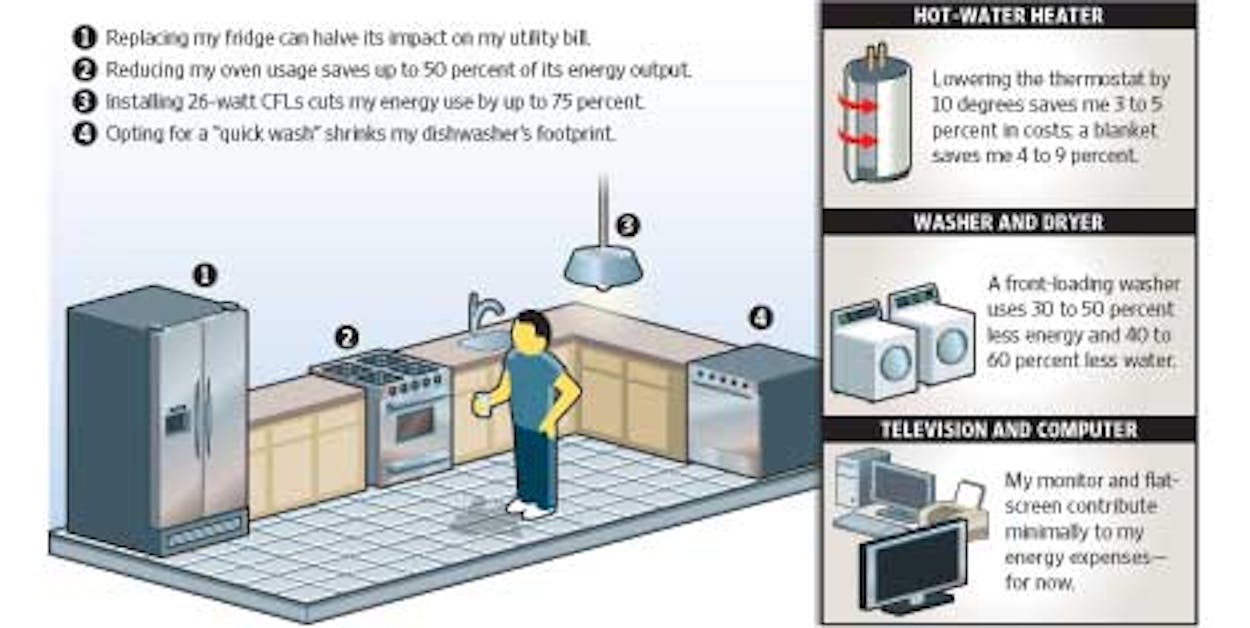

I bought half a dozen 26-watt CFLs for about $5 a bulb, or $30 total, to replace a few of my home’s 100-watt incandescents. That was about twice what I would regularly pay, but if I was doing the math right, I’d make the $15 back in a year. Then I’d start making money on the things, since they last four to six years. So I quickly set about replacing all twenty of my lights. I had thought this might be a pain because we have some odd-sized globe bulbs in our bathrooms and track lights in the den. But Home Depot had both types, and I also learned that I could have saved myself the trip by going to 1000bulbs.com. Depending on whose estimate you believe, lighting represents 5 to 25 percent of one’s electricity bill—in my case, between $150 and $750 a year. Since CFLs use up to 75 percent less power than incandescents, I’m saving anywhere from $110 to $560 a year—let’s average it at $335—and reducing my carbon footprint by two thousand pounds (see “Progress Report”).

CFLs have taken heat lately for the recycling problems created by the mercury they contain. But it’s worth pointing out that CFLs still contribute less mercury overall than incandescents do: The latter require more electricity, and coal-fired utility plants are by far our chief source of mercury emissions. And that assumes I won’t drop off the bulbs at my county’s hazardous-waste disposal center or the nearest Home Depot for recycling when they finally burn out—which I will.

In the best obsessive-compulsive tradition, I’ve since turned my attention to my other home appliances. Here’s what I’ve found:

Washer and dryer. No problem here. Our new Bosch Axxis front loaders, part of some kitchen remodeling last year, are probably saving us roughly 3 percent of our electric costs per month because (a) front-loading washers use 30 to 50 percent less energy than top loaders, (b) our particular washer has been judged 60 percent more efficient than required by the Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star standards, and (c) we’re using cold water only (80 to 85 percent of washing costs go to heating the water) and trying to dry with natural air rather than heated (similar differential). A green bonus is that front-loading washers also use 40 to 60 percent less water.

Cooktop. Our Wolf gas unit is probably reducing the 5 percent of energy used in cooking by some amount. But gas is only marginally cheaper than electricity these days, and it packs its own footprint problems. We’ve achieved minor savings by using our microwave and toaster oven in place of our gas oven as often as possible, saving up to 50 percent of its energy output when we do.

Dishwasher. It’s not Energy Star—approved. But I haven’t thought about replacing it because it’s only six years old, and a tip from our energy auditor at TXU has helped us reduce the roughly one percent that it contributes to our home costs: We now use the “quick wash” function (no prerinse cycle) and set the machine to dry the dishes with natural rather than heated air.

Hot-water heater. This is a biggie, since hot water drains about 20 percent of our utility bills. My tank is gas heated and relatively new, but I’ve had my plumbers fit it with a pump that keeps hot water in our pipes, at the ready, so that we don’t waste energy firing up the tank. I’ve also wrapped it in a “blanket” that keeps water hot for longer—saving about 4 to 9 percent on heating costs—and I’ve lowered the thermostat (each 10-degree reduction in water temperature can save 3 to 5 percent in energy expenses). At the same time, I’ve begun looking at “tankless” heaters, which can be up to 34 percent more efficient than conventional models. This popular new technology eliminates the tank from the process, saving water and the energy wasted on storage; instead, when you turn on the faucet, water flows directly through a heat exchanger, which warms it. Tankless rigs are two to three times more expensive than standard heaters, but as with CFLs, they eventually pay for themselves.

Refrigerator. Alas, our Kenmore is a green clunker, and that has my attention, since fridges use more energy—7 percent—than any other kitchen appliance. Oh, it has all the bells and whistles, like front-door water-and-ice dispensing. But these just burn more electricity. Replacing it would reduce its contribution to our bill by about half.

Television and computer. The two appliances I use the most hours each day represent another tiny percentage of my monthly utility nut (I’m not sure exactly how much because it’s difficult to separate out these smaller devices). That may change, since I’ve just bought a 42-inch flat-screen LG, but not much. Besides, if there’s anything I’m not going to sacrifice for greening, it’s having the best television I can afford.

All this sweating the small stuff adds up to somewhere between 10 and 25 percent savings on my total utility bills—which, if you average at 17 percent, comes to about $700 a year. Nothing huge, but it’s something. And I’m so taken with my new green gadgetry, I drop by Current Energy whenever I’m in the neighborhood. Of course, on my last visit, I ran across an item that suggested that even greening can reach a point of diminishing returns. It was a $400 electric composter—an expensive oxymoron, it seems, if ever there was one. True, the gadget uses only five kilowatt-hours of energy a month, about 50 cents’ worth. But that’s more than my backyard compost pile costs, which is precisely nothing. And anyway, owning an electric composter really would be geeky.

Progress Report:

This month’s effect on my carbon footprint, wallet, and happiness.