So just what is a rock star, anyway? The term is universally recognized—can there be a better night out than one that begins with rock star parking and ends with partying like a rock star?—but its meaning falls into the know-it-when-I-see-it category. A rock star has a specific appeal, partly danger, partly sex, and partly that most intangible of qualities, cool, and it grabs enough people that he gets to ignore the rules the rest of us play by. But the magnitude of the fans’ response is as important as the attitude that attracts it, and you can’t be a rock star without both. So though Elvis Presley was a rock star, Elvis Costello is not—too few fans. George Jones is; George Strait is not—too little danger. Bill Clinton enjoyed both, but George W. Bush doesn’t, nor does he want to; he came by his fans precisely because he’s not a rock star. (Poor Al Gore has no place in the discussion.) So where is the line? Do you have to have as many girls faint at your head fakes as John or Paul, or will Ringo’s numbers suffice? Do you have to change outfits as many times per show as Britney Spears or just as often as David Lee Roth?

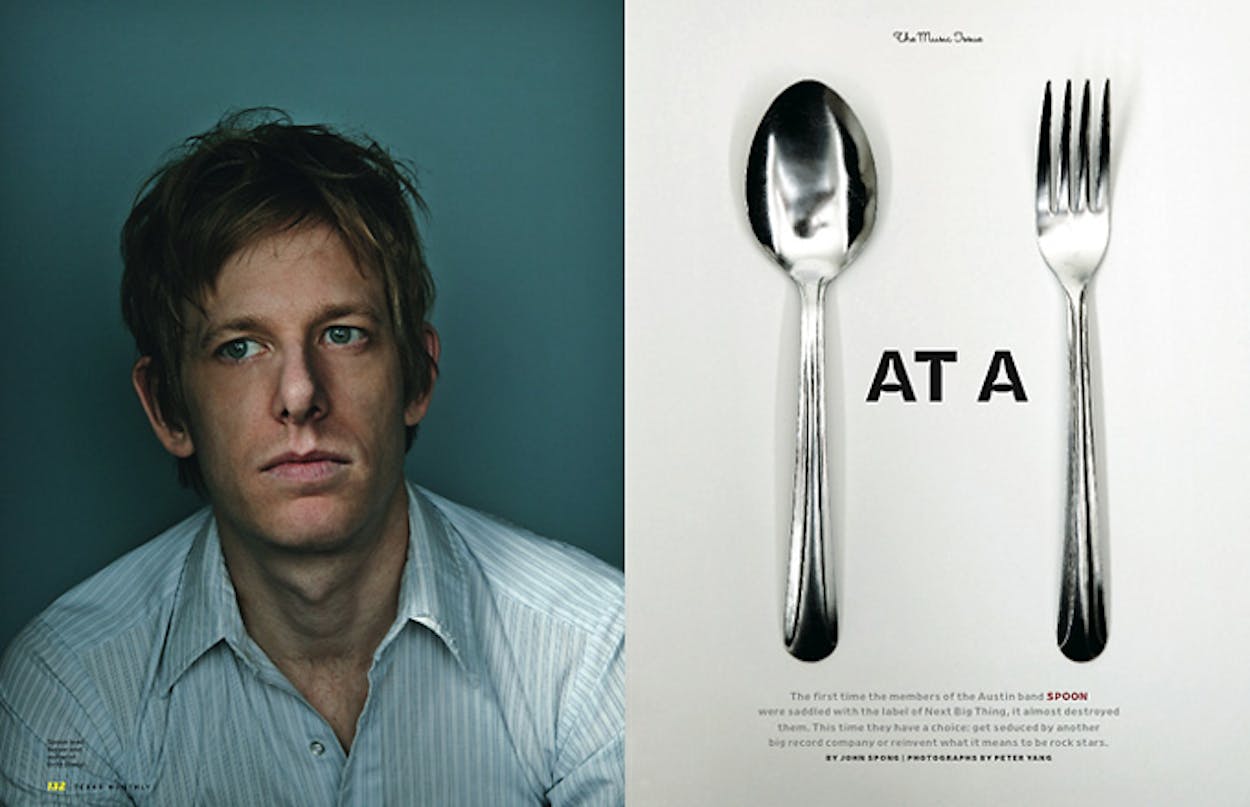

Britt Daniel, the cagey, sometimes caustic leader of the Austin band Spoon, claims to have no idea. “I don’t know how you define ’rock star,’” he says. “But I’m pretty sure water doesn’t leak into the trunk of his Mazda whenever it rains.” Don’t be fooled. Daniel may not be in a position to trade his hatchback for a Humvee, but a beat-up Mazda better fits his image anyway, an anti-style of rumpled corduroys, wrinkled Arrow dress shirts, and permanent bed head. That’s how he looks in line at a taco stand in Austin and onstage at packed 1,500-seat venues on both coasts, playing multi-night stands for hip kids who follow his every herky-jerk toe tap as though he were a Liverpool moptop himself. His music, simply irresistible pop the first time you hear it, is deceptively complex and aggressive underneath, as Buddy Holly might have sounded if he’d listened to nothing but Prince in high school. It has seen the top of the college radio charts in the alternative-music bible CMJ, along with being featured on last year’s two new television phenomena, Queer Eye for the Straight Guy and The OC. And last September Time magazine, spotlighting current trends in a special “What’s Next” issue, titled its Spoon piece “These Guys Just Might Be Your Next Favorite Band.”

But Daniel and Spoon have more than buzz on their side; they have timing, hitting their stride just as the record business enters a new Golden Age for Indies. After a decade of major-label mergers and declining record sales, the music industry is now dominated by five mammoth majors that have no patience, with their ears or their wallets, to give acts without hits time to develop. But when the mainstream narrows, the margins widen, and that’s where the indies operate. Small, self-financed record labels have always been the best alternative to the majors’ flavor of the fiscal quarter, and now that the Web gives world-wide reach and cheap recording software allows garage bands to make CDs without leaving the garage, the indies’ job is easier than ever. Their exponentially lower overhead lets them survive on fractional sales and still, believe it or not, get more money to the artists. So a band like Spoon actually had a bigger payday selling 65,000 copies of their last CD on tiny Merge Records, of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, than they would have had selling a million at a giant like Universal. What all this means is that a major-label deal—and the kind of five-million-units-or-bust measure of success that goes with it—no longer has to be the dream. In fact, if you’ve never even heard of Spoon, Spoon doesn’t care. Perched as they are as everybody’s favorite indie act, they are the new rock stars.

Britt Daniel, 34, looks like a nerdy college kid working on his homework. He’s sitting Indian-style on the floor of a small recording studio in the garage of Spoon drummer Jim Eno, deliberately using his long index fingers to press out a low, two-note piano riff on an electric keyboard. It’s the middle of January, and the band is recording their fifth album, which they hope to release this fall. Specifically, they are working on a song called “The Breaks” that Daniel says may or may not wind up on the finished record. The part he’s playing bumps along—ba dum ba-dum, ba dum ba-dum—through the length of the song, undergirding another piano part he’s already recorded. The only other ingredients are a bass guitar played by Spoon member Josh Zarbo, which shadows the bass line played by Daniel’s left hand, and Eno’s drums, a slow, swinging pound to the kick drum and snare that would signal a waltz if it were played in a dance hall instead of this garage.

“What are you going to do with the new piano part?” asks Eno while Daniel, unhappy to have missed a slight variation in rhythm on a transition from a chorus to a verse on the first take, waits for the tape to rewind so he can make a second pass.

“I’ll either use it with the other left hand,” says Daniel, “instead of the other left hand or not at all.”

You shouldn’t read into that exchange that Daniel is winging it, that he’s flying by the seat of his cords. Of all the hallmarks of Spoon’s sound present in “The Breaks”—the rudimentary riff, the quiet space left in the music, and the way Eno’s steady rhythm holds it all together—the primary quality of a Spoon record is that it sounds exactly the way Daniel heard it in his head. While that may not seem like the best way to describe a record’s sound, it fits Spoon, because if you listen long enough to any of their music, you’ll eventually be grabbed by Daniel’s thorough control. The key is his discipline, as a songwriter and as a producer. No matter how hummable the melody, he never lets it linger. No matter how cryptic the lyric, he never explains. And no matter how curious the sounds in his recordings—violas, mellotrons, vibraphones, static, feedback, hand claps layered with reverb, rhythm tracks comprised of door slams and Daniel’s voice, bits of stray conversation picked up on the mike and left in the track—they never get sloppy or dominate a song. A place for every sound, and every sound in its place.

That’s the thread running through all of Spoon’s seemingly disparate recordings: the careening punk of 1996’s Telephono; the jagged new-wave of 1998’s A Series of Sneaks; what Daniel terms the “classic soul” of Spoon’s 2001 breakthrough Girls Can Tell; and 2002’s Kill the Moonlight, the singular, stripped-down masterpiece that found Spoon, once maligned as a knockoff of eighties punk gods the Pixies, breeding imitators of their own.

Pulling it off is no casual task. Most Spoon songs are born with Daniel playing a guitar or a keyboard into his four-track recorder, usually sitting on the couch in his apartment. He’ll flesh out a song as best he can, or as much as he wants, recording successive versions to add percussion, bass, and vocals, and keeping precise notes on a recording’s progress on legal pads. It’s an ongoing process, and the tapes with songs he’s still working on are stacked neatly on his coffee table next to the four-track, while the retired tapes, representing the genesis of every song he’s ever written, are kept with their corresponding notepads under his bed. They’re numbered, beginning with the first tape he made when he bought the recorder, in 1989. He’s up to tape 72.

“Everybody who uses four-track does this,” he says. “It’s not my own thing. But it’s the only way I know to be good.” And the proper place to experiment and figure out what he will want when he gets to the studio. “I was working on the vocals for ’Waiting for the Kid to Come Out’ [on 1997’s five-song EP Soft Effects], and when I listened back to it, I accidentally heard an earlier, completely different vocal track play with it. I thought, ’That sounds pretty cool. Let’s do that when we get to the studio.’” It worked. In the song’s bridge, two Daniel vocals split your attention, singing different lyrics over each other until joining together to scream the chorus. It’s disjointed, then dramatic, and all by design.

It’s the notes from those tapes that Daniel takes to the studio to work out with Zarbo and Eno. Zarbo is the band’s little brother, the butt of most of their jokes. But his steady bass lines and harmony vocals are a big part of how the band manages to replicate their studio success on stage. And Eno is Daniel’s musical better half. He’s been in Spoon since Daniel started the band, and his training as a jazz drummer taught him to roll smoothly through all manner of stops and starts and quirky tempos, a vital skill for playing behind Daniel. Eno’s day job designing microchips has helped too, allowing him to build the studio and help finance Spoon’s recordings. As he and Daniel have become increasingly adept at working the recording board, they have been able to take their time making albums. It helps that there haven’t been any label execs hounding them for a hit.

“Josh likes to make like he’s [Motown bass player] James Jamerson,” says Daniel. “He’s more studied in theory than I am. Jim is pretty calculated when it comes to his parts. He likes to add something to it to surprise you rather than just lay down a backbeat.” But it’s ultimately Daniel’s band. “Britt will have a very clear vision of what he wants,” says Austin producer John Croslin, who sat at the board for Telephono and A Series of Sneaks. “He’ll try everybody’s ideas, but if it veers too far from what he wants, he’ll cut it off.”

The formula worked on Spoon’s first four records, and it’s still in place for the fifth. Here in Eno’s garage, after recording a guitar part for another new song, “I’ve Been Good Too Long,” Daniel turns his attention to vocals. He grabs a couple of beers before looking over his notes, dimming the lights, and slipping on a pair of headphones. Then he bellies up to the mike. “Good Too Long” begins for maybe the tenth time in the past hour but this time with words. Daniel slurs and gasps the lyrics: “You were a fly by night/No mind, no plans/I was a practiced mark/Listening to the weatherman.” He moans, hiccups, jumps in and out of falsetto, races to squeeze words into the groove: “Said you got to fight when you know you’re right sometimes/We all act like we know what that means.” Here’s where Daniel injects a sense of urgency, where he hints at letting go, where he reminds you that, no matter how concise the rest of the song may be, this is in fact rock and roll: dangerous, sexy, and above all else, cool.

The members of Spoon are tired of talking about their short stint with a major label. That was back in 1998, when the band was officially the Next Big Thing and Elektra Records was offering them the traditional route to stardom. The relationship ended in disaster, and these days Daniel, open and animated when the conversation sticks to music, looks like he might run from the room when talk turns to the music business. “I don’t want to do a whole article on Elektra,” he says.

Although some fans were disappointed when Spoon chose Elektra to release their second album, A Series of Sneaks, the decision to go with a major made sense at the time. They’d been signed by Ron Laffitte, the head of Elektra’s A&R division, the department that oversees the development of new talent. And they’d recorded Sneaks on their own before licensing it to the label, meaning not only that Spoon had had complete control when they’d recorded the album but that they would ultimately own the recording itself, a rare allowance from a major. Sneaks sounded leaner and brighter than Telephono; it was short and to the point, fourteen songs in 33 minutes, brimming with hooks, energy, and the unexpected. It should have been a hit.

But things soured quickly. According to Daniel, Laffitte stopped returning his calls and never attended a single show after signing the band. (Laffitte, now the president of A&R at Columbia, didn’t return calls for comment.) In a weird move, Elektra insisted on adding thirty seconds to the album’s first single to make it closer in length to everything else on the radio. None of it felt right to the band. When the album was released, in May 1998, Spoon received scarce advertising and a cut-rate tour budget. It had not even sold three thousand copies when, early that September, Laffitte left the label, meaning the band had no one at Elektra to lobby on their behalf. That same week they were dropped.

Daniel depicts the immediate aftermath as a “lost period.” He moved to New York and put on a tie to take a day job as an administrative assistant at Citibank. On his lunch break one day, he went to pick up registration materials for a music conference and ran into the drummer for punk-rock group Sleater-Kinney. “I was dressed up in my Citibank outfit, and she said, ’What are you doing?’” Daniel says.

“I did think for a time that I’d have to stop making music,” he adds later, “which I could have handled. But it was going to break my heart.”

Music had been Daniel’s focus since growing up in Temple, a Central Texas hospital town, where he spent much of high school combing British music magazines and picking out melodies on a bass guitar while watching MTV. Friends remember him as a rock star even then, plenty intellectual and a little bit alienated. He was into Prince, the Cure, Spacemen 3, Julian Cope, music you’d never hear on pickup truck radios in the Temple High parking lot. “Yeah, I was the coolest kid in high school,” he says. “It’s just that nobody else knew it.”

He formed bands as soon as he got to the University of Texas, in 1989, meeting Eno in 1993 and starting Spoon a year later. The band’s blistering yet hypermelodic punk quickly earned the buzz they would ride through Sneaks, and they started recording almost immediately. A handful of labels offered to release Telephono, but Spoon went with Matador, in part because it was the home of their favorite acts, like Pavement, Liz Phair, and Yo La Tengo. But Telephono received mixed reviews, and Spoon learned quickly that being a big dog in Austin didn’t necessarily translate on the road. Still, they found pockets of support.

“We were in Fargo one night in October,” says Eno. “It was about to start snowing, and you could see it in people’s eyes: They were getting ready for their long, alcoholic winter. There was one guy there in a trench coat who paced back and forth in front of the stage the whole show. Miserable. So the next night was in Omaha, and we figured it would be just as bad. We set up our equipment in the club that afternoon and left and didn’t get back for the show until about five minutes before it started. And there were twenty-five to thirty high school kids there who just worshiped the band. After the show, they invited us to go hang out at a bowling alley across the street, then to a karaoke bar, and then to somebody’s house to drink beer all night.” Among the locals was Conor Oberst, who, at seventeen, had already started his own record label and his own band, Bright Eyes, but was still a good five years away from being called the next Bob Dylan in publications like the New York Times.

After the train wreck with Elektra and Daniel’s New York hiatus, the band regrouped in Austin in the fall of 2000 and then went on the road. In a sense, Spoon has always been two bands, controlled inventors in the studio lab but a furious live act. Now they had real frustrations to take out onstage. That summer they had released a scathing two-song kiss-off to Elektra, “The Agony of Laffitte” and “Laffitte Don’t Fail Me Now,” on Oberst’s Saddle Creek Records. The single provided a convenient hook for stories in alternative weeklies in towns where Spoon went to play. Their shows started attracting an intensely loyal following of kids who were growing up like Daniel had, proud to feel as though they’d found something no one else knew about.

Then Spoon released a third album. Girls Can Tell was yet another departure, a more straightforward pop-rock record than its predecessors, a reflection, says Daniel, of the classic rock radio he had listened to in New York—lots of Supremes, Marvin Gaye, and the Kinks. The band shopped an early version of Girls for about a year before completing the record and accepting an offer from Merge, the label started in 1989 by members of edgy pop group Superchunk as a refuge for like-minded bands. After Merge released it, in early 2001, little signs indicated that Spoon’s fortunes were changing. Critical praise came from the anticipated alternative sources, like the Village Voice and L.A.Weekly, but also from the Washington Post and the Toronto Sun. The first week’s sales equaled the first ten months’ for Telephono, boosted by a glowing NPR segment on the band. The video for Girls’ opening track, the soulful, spooky “Everything Hits at Once,” started showing on the Jumbotron over Times Square. And the little clubs they’d always played in places like Boston, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and L.A. could no longer hold enough people.

After The New Yorker and a dozen other publications put Girls on their year-end ten-best lists, Spoon took a full head of steam into the studio for 2002’s Kill the Moonlight. Here was Spoon at their finest: the risks and energy of Telephono and Sneaks combined with the maturity of Girls and delivered with a swagger emboldened by the critical acclaim and wide fan support they felt they’d always deserved. The Chicago Tribune said the record “confirm[ed] greatness for Spoon.” At music festivals across the U.S., like the Austin City Limits fest and New York’s Downtown River to River festival at Battery Park, the largest crowds assembled for the Spoon set. The band appeared on Conan, Carson Daly, and Austin City Limits. Major labels started calling again with offers for the band. Last fall, an executive at Elektra even e-mailed to inquire whether Spoon had decided what label their next record might come out on. “I just told them to talk to our manager,” says Daniel, “who asked if they were aware of our history in that building. It makes me feel like those people are a little out of it.” Spoon, on the other hand, was finally in.

“I remember being in a club in Boston the first time somebody asked me if I liked indie rock,” says Daniel. “I thought he meant bands making records on independent labels. Then I realized he was talking about indie rock as a genre, not a method. I thought he must have been an idiot.” Credit the confusion, which comes up frequently when a hard-to-peg band like Spoon is written up in a daily paper, to lazy critics and A&R reps. In their rush to find the next Nirvana after the Seattle punk trio’s Austin City Limits remade popular music in 1991, music industry types who thought “grunge” too narrow a term to describe all the acts making the jump to major labels chose “indie rock” as a broader category. It gave no indication of what a band might actually sound like, but it worked its way into the lexicon anyway.

But what is a joke as a genre has never been more important as a way to make records. Despite an improved first quarter in 2004, major labels have been slumping for years, and indies have picked up the slack. “Majors are being much more selective now,” says Bill Bentley, a vice president at Warner Bros. Records, “so signing bands who aren’t quite ready will often fall to the indies. Majors have to be able to do something with an act when they sign it.” Bentley and other execs cite a handful of reasons for the change, from free downloading off the Internet to a poor economy to the lessons learned from all those next Nirvanas nobody can remember. Conor Oberst, who was fourteen when he started Saddle Creek with those same Omaha friends who went with him to see Spoon, calls it differently. “Majors make music for people who don’t like music,” he says. “They cater to people who buy five CDs a year.” And so, the logic goes, majors need only make CDs by five artists a year. And hopefully sell 15 million copies of each.

Their smaller scale isn’t the only thing that distinguishes indies. They tend to be run by fans for fans, and they pride themselves on forming real relationships with their bands. “When Spoon’s A&R guy left Elektra,” says Merge’s publicity director Martin Hall, “nobody at the label knew who they were. Everybody at Merge knows Spoon.”

The Merge-meets-Spoon story is a perfect example of what an indie can do for an act. Spoon licensed two completed records to Merge, meaning the band didn’t owe the label any money for production and could start receiving their indie-standard 50 percent split of profits almost immediately. At a major, Spoon would have received a royalty rate closer to 9 percent, and that money would not have come in until Spoon had paid back whatever advance they had received, plus any money that had been spent by the label on marketing and videos, which can run into the millions of dollars.

“There’s a misconception that independent record labels don’t want to sell records,” says Merge president Mac McCaughan. “But the economics are that we don’t need to sell as many, and that allows us a certain flexibility to deal with each band and record differently.” That way, the label doesn’t automatically throw a bunch of money at a release, instead targeting fans already in place. In Spoon’s case, that meant getting reviews in the magazines and Web sites Spoon fans read, like Spin and Pitchforkmedia.com, and shows in the places where the fans live. Then, when record and ticket sales indicated that momentum was starting to build, Merge got review copies of the records to general-interest publications like GQ and Vanity Fair and started to spend on videos. It’s a marketing scheme based on and conducive to a natural growth of the fan base. “It’s taken talent to get to that spot in people’s consciousness,” says Spoon’s tour manager, Ben Dickey, who runs his own indie label, Post-Parlo Records, in Austin. “Spoon is getting bigger crowds now, and there are some casual fans there. But the great thing is, the people are staying for the whole show. There’s not been one big hit, so no one’s there for just one song.”

That the hit song is no longer the brass ring is a plus in more ways than one. Spoon’s friends Fastball were Austin’s other Next Big Thing in the summer of 1998, and by that September, when Spoon was wondering if they should quit music and go to grad school, Fastball’s hit song, “The Way,” was being played between innings in every ballpark in America. And Fastball’s album, All the Pain Money Can Buy, released just two months before Sneaks, had sold more than a million copies. But just as quickly, Fastball disappeared, and although they’ve recently resurfaced in Austin, the rest of the world won’t likely be aware of them again until Time-Life introduces its “Ultimate 90’s Collection” series. Although Spoon’s sales will probably never match Pain’s, it’s a safe bet that Spoon has more true fans among the 65,000 who bought Moonlight than Fastball ever had.

A better target for Spoon is the success of a band like Wilco. The Chicago pop outfit has never had a hit song or even much radio play. But they have been the critics’ pet for nearly ten years now, increasing their attendance figures and record sales the same way Spoon has, through steady touring and well-crafted records. Their last one, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, sold 434,000 copies, but not until after their own hard-fought split with a major landed them at Nonesuch Records, a small boutique subsidiary of that same major. The example is well-known to Spoon. Last year they turned their business over to Tony Margherita, a Chicago-based manager with one other client: Wilco. It was another indication of the direction Spoon was heading. And while Margherita will not talk specifically about his hopes for either band—no need to put pressure on the boys—he will say it’s not unrealistic to expect Spoon to double their current sales when their next album comes out in the fall. At 130,000 copies, they’d be well on their way to Wilco.

The members of Spoon, of course, don’t profess to aspire to be anybody but who they are, and they are happy that being the Next Big Thing is somebody else’s problem this time around. “All I really ever wanted,” says Daniel, “was to put out records, ones I’d be proud of, and have that be the main thing I was doing with my life.” That may not strike you as the musings of a rock star. But whose definition are you using?