New York City, 1964. Our heroes, Dan Jenkins and Bud Shrake, are waiting for the Time-Life coffee cart to make its morning trek through the offices of Sports Illustrated. It was only a few hours ago that Dan and Bud, sportswriters extraordinaire, finished their nocturnal tour of Manhattan: Toots Shor’s, P.J. Clarke’s, Elaine’s, a river of scotch and water running between them. It was at Elaine’s—or was it Clarke’s?—that they ran into our heroine, Liz Smith, who was working for both Sports Illustrated and Cosmopolitan. Now, as anyone who has lived in Manhattan can tell you, seeing three native Texans together is not alarming. These days, such confabs are even known to happen in Brooklyn. But what was remarkable about Dan and Bud and Liz was that they all arrived here, at the penthouse floor of magazine journalism, by way of the very same Fort Worth high school.

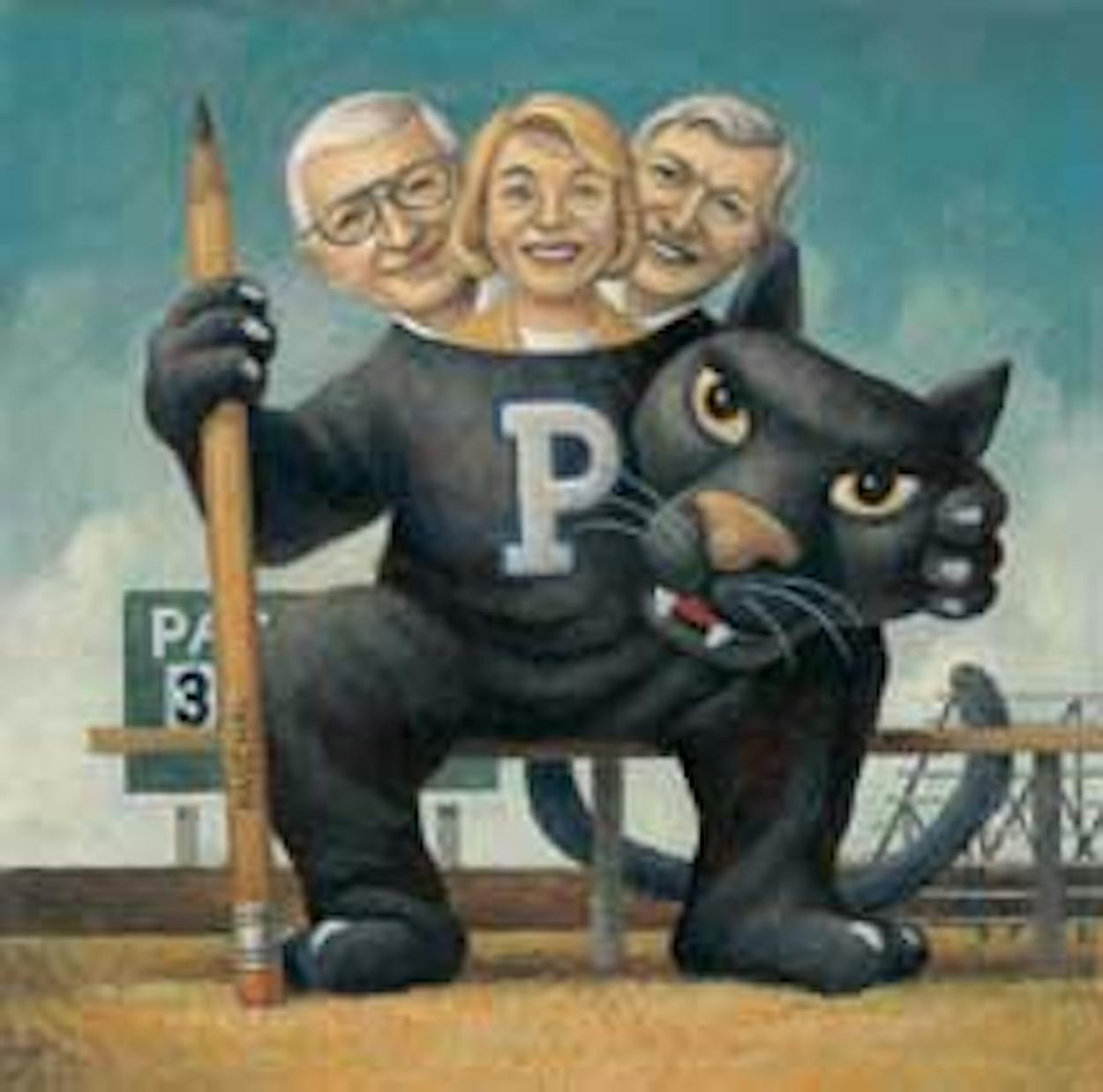

R. L. Paschal is a cream-brick building on Fort Worth’s south side, primarily known these days as a proving ground for National Merit Scholars. But for a brief moment in the sixties, Paschal was Sportswriter High. The disgorgement of so many top-drawer writers hardly caused a ripple among the alumni. “We all thought it was such a cool deal to go to Paschal that it didn’t surprise me at all,” Shrake says. Jenkins’s motto back then was “Don’t trust anybody who didn’t go to Paschal,” and since New York literary circles were swarming with Paschalites, he didn’t much deviate from it.

We relate this small curiosity because it was very much on the mind of a fourth sportswriting prospect—the name you see at the top of this page—three decades later as I toiled at the Pantherette, the school newspaper. As a young pup (then grandly assuming the title of “sports editor,” as if I commanded a whole battalion of beat writers), I knew about that era of Sports Illustrated and was determined to remake the school paper as such. Results varied. When one of the school’s coaches grew tired of my queries, he would turn on his Weedwacker and resume trimming the field. A controversial report, issued in the Pantherette just weeks before my graduation, suggested that some of my classmates who played on the baseball team had failed to provide sufficient leadership down the stretch. The ballplayers did not seem to mind (I suspect they didn’t even read the paper), but one of their mothers confronted me in the parking lot and said in no uncertain terms that the article represented a betrayal. It was at that moment that I knew journalism would be my career.

But, oh, to be a Fort Worth kid in Manhattan in 1964. In five minutes you would know that the clubs were a bit more glamorous than the gambling joints you could find on Jacksboro Highway, that Times Square’s porno allure outpaced even the downtown brothels’ back home. Sports Illustrated was in a kind of golden age too, with fat expense accounts for the writers and a managing editor, André Laguerre, who demanded that Jenkins and Shrake insert themselves bodily into their stories—that sardonic, world-weary Texas voice seeming to ooze out in every sentence.

It was Jenkins who would parachute into the “thundering zoo” of Fayetteville, Arkansas, in 1969 to watch the Texas Longhorns football team overcome “what seemed like the safest lead since Orval Faubus rode in a motorcade.” It was Shrake—the tall, handsome guy who was never short on big ideas—who reported that Lamar Hunt, the oil scion and owner of the Dallas Texans, had “been seen at league meetings with holes in his shoes.” Smith, well, she didn’t know beans about sports, but what of it? Laguerre made her the magazine’s roving correspondent of fabulousness. She toured the newly built Astrodome, and she interviewed Sean Connery on the set of a James Bond movie, the great Scot letting a towel tumble off his midriff in midsentence. It was sort of like being in a locker room, anyway.

You could see the unformed clay of their personalities back at Paschal: Jenkins, class of 1948, is whip-smart, has a slick black Ford, talks like Jimmy Cagney at the age of 18, and shows literary promise when not gulping down coffee at Herb Massey’s restaurant. (“Dan could drink an incredible amount of coffee,” Shrake says. “I’m talking, like, Balzacian.”) Shrake, class of 1949, is only one year behind Jenkins academically but several more socially. He cites as a seminal high school moment being invited to sit with Jenkins in his Ford at the Pig Stand, on Eighth Avenue. He eventually matches his friend in early-onset sophistication and highfalutin literary ambition and announces that he will publish his first novel by the time he is 28 years old (and almost makes it). Smith, class of 1940, once wrote about her days in Fort Worth: “All I can remember about going to the sainted Robert Lee Paschal high were lessons from or about the opposite sex.” I will let that hang there significantly like an item in her gossip column.

I too have since left for New York, the lure of sportswriting outweighing Paris Coffee Shop, the Fat Stock Show, and Mom’s watchful eyes. But on a recent visit back to Fort Worth, I sat down with Jenkins, who has published a new novel, The Franchise Babe, which will be released in June. At 79, he still carries himself like the captain of the golf team and has a voice that is soft but pungent, one that makes you lean in and really listen. He pointed out that the Paschal invasion of Sports Illustrated was in fact part of a much larger invasion of the Big Apple. “When I lived on Eighty-sixth Street between Madison and Lexington,” he said, “there were five people living there who had all gone to Paschal at the same time.” Going downstairs to get the newspaper was like being in homeroom.

Normally the Trollope of the men’s professional golf tour, Jenkins turned his attention to the women’s game—“Lolita golf,” in his priceless formulation—in The Franchise Babe. “First of all, they can outdrive me,” he said of the young female pros. “And they’re fearless. And they’re cocky. They’ve all been to the Ledbetter Academy and they know what they’re doing. And a lot of them are really cute.” When it comes to one Tiger Woods, Jenkins is not ready to surrender the title of Greatest Ever. “I don’t think I’m ever going to put him ahead of Ben Hogan,” he said. “He’s my guy.” Hogan, I might mention, also attended Paschal.

After we finished up, I drove down Berry Street, then took a left on Forest Park Boulevard, for a long look at old Paschal High. Lacking a glass of scotch and water, I raised a hand and saluted the House That Dan and Bud and Liz Built.