This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Every year the public is primed like an old wooden pump to put out for the latest gear on the hi-fi scene, and every year, a lot of the new products that hit the market also hit the floor—out for the count. Why? Because, despite the fact that they were labeled “new,” most of them were simply boring. On close inspection, they turn out to be variations on themes that were once revolutionary but are now standard, or they are impractical, unnecessary, and too expensive. Quadraphonic sound (which was going to ravish your ears from four sides at once) and the videodisc (which promised you the luxury of screening the vintage movie of your choice on your own TV) spring to mind as two of the most ballyhooed nonhappenings of the last few years.

But last year was different. Last year the so-called march of technology made some genuine progress in the state of the art of home entertainment, bringing us back to the basic idea that the purpose of stereo equipment is to reproduce sound as faithfully as possible. The new equipment on the market today aims to enhance music reproduction, make stereo systems easy to operate and live with, to do anything, in fact, that will make listening to music as pleasant and hassle-free as it can be.

In 1976, three major movements surfaced in the hi-fi/home entertainment industry: a trend toward miniaturization, the integration of computer technology into hi-fi equipment, and an influx of new industrial design talent.

Miniaturization is an idea whose time has come. In our modern culture big has always meant better and small has meant substandard, but that concept is fast going the way of the 75-degree thermostat setting. A large hi-fi system, like the home media center, is great if you’ve got room for it, but what if you don’t? If you live in an apartment or condominium, or if you simply want to listen to music with a minimum of clutter, miniaturization will appeal to you. One of the hottest products out today is the ADS 100 speaker, which you can hold in the palm of your hand. Produced and marketed by ADS in the United States, the 100s sound as good as speakers that cost much more (they’re $100 apiece) and are six to seven times larger. The fact that it is miniature definitely adds to its mystique. While I was researching this article, I strolled into a hi-fi dealership and found all the salespeople and customers sitting around listening to a pair of ADS speakers, marveling at the quality of the sound. The rest of the speakers, from small to middle-sized to huge, stood silent.

Miniatures have always fascinated people—remember Dick Tracy’s two-way wrist radio?—but only in recent years has fantasy become reality. We are entering an era in which high-quality, easy-to-operate musical reproduction will be available to you wherever you are: at the beach house, in the car, on your bicycle, in the tub, or—the ultimate dream of audio freaks—in your ears in the form of tiny amplifiers. Who knows, the day when you can have a hi-fi system implanted in your brain may not be far off (I’ll take two—one for each hemisphere). What miniaturization means to you is that the hi-fi industry has decided to take your lifestyle seriously. If you want mobile music as good as anything you can hear at home, they’ll make it for you.

The second major trend in home entertainment this last year has been the hookup of computer technology with equipment design. One new product in particular—the Audio Pulse Model One ($650)—demonstrates what this means. Put quite simply, the Audio Pulse makes your puny apartment sound like a concert hall. What it does is add multiple, split-second delays to the music that is being played, thereby giving the effect of reverberation, which is what a concert hall is all about. The Audio Pulse can be attached to your present stereo system with a little adjustment: it requires four channels of amplification and four speakers (although do not confuse it with quadraphonic sound). It is easy to install and use and it really opens up your listening room.

The third notable trend in the hi-fi industry has been the influence of top-name industrial designers on new equipment. Ride in a car with a seat that’s too small or a door handle that’s out of reach and you’ll better appreciate the importance of industrial design in terms of function. Industrial design also has impact on the aesthetics of a new product: it will determine whether a particular piece of equipment is shiny or dull, angular or curved, black or white. In personal terms, industrial design can prejudice your opinion of a product, either for good or for ill, and materially affect your enjoyment of it.

In 1976 an important new equipment designer appeared on the hi-fi scene. Mario Bellini is an Italian architect/industrial designer who many think is one of the top five in the world. He has products in the Permanent Design Collection of the Museum of Modern Art. He has designed several contemporary furniture classics, and last year he turned his talents to designing hi-fi equipment. His most striking new product in 1976 was a tape deck design for Yamaha, the TC800GL ($400). The TC800GL eschewed the de rigueur gleaming stainless steel for a slate-gray plastic epidermis. The shape of the deck was equally unique: a wedge, not a rectangle. In redesigning the deck, Bellini took a clunky piece of equipment and turned it into acoustical sculpture. He also made it versatile enough to play on batteries, in your car or at home.

You’ll see a lot of black equipment this year, and not just in Bellini’s designs. It’s all part of a new breed of “laboratory look” components. For an example, check out Advent’s Model 300 receiver ($260) or Nakamichi’s Black System One ($1900), which is a cassette deck, timer, preamplifier, and amplifier all housed in a gleaming black rolling rack. Not incidentally, Yamaha’s new top-of-the-line B1 amplifier ($1600) and Cl preamplifier ($1800) are also jet black.

Along with the major stereo developments, there is a minor “trend” also worth mentioning: lower cost for higher performance. Because of the high-tech advances that go into products, the money you spend on a sound system will get you better reproduction than ever before.

Home Is Where the Tube Is: The Media Center

Once upon a time the houses of well-to-do, educated people had libraries. You remember libraries—big rooms with comfy armchairs and shelf upon shelf of books. Surely you remember books? Well, friends, if the day of the library is over, the day of the home media center is at hand, bringing the ubiquitous screen just one step closer to total control over our leisure hours. It is not inconceivable that in five years a media room will be just as important as a bedroom or kitchen.

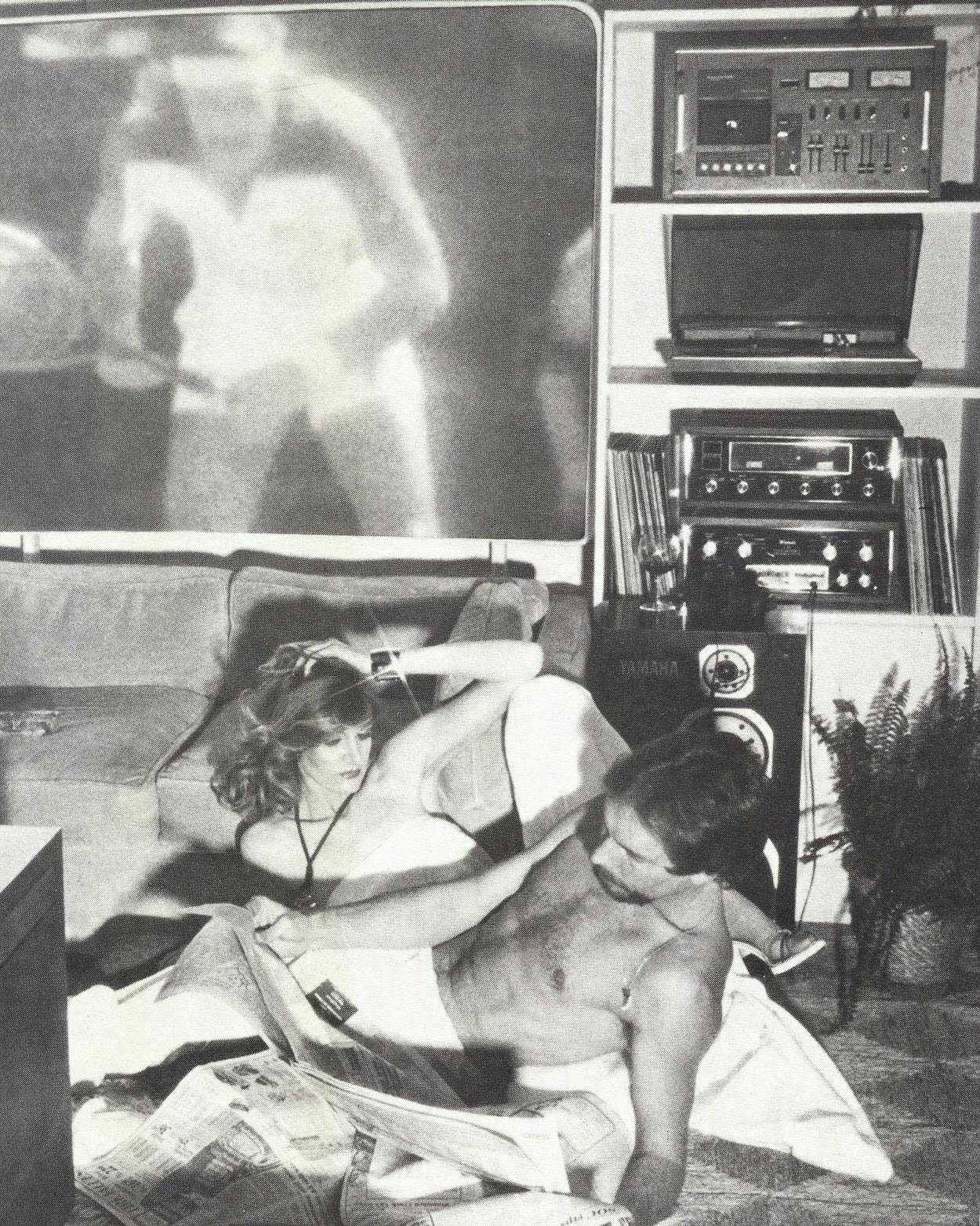

If you don’t want to wait five years, you don’t have to, because audio and video components are available today to turn any room into a home media center. By definition the home media center has two major sections—an audio system and a video system—which operate together to provide a virtually unlimited range of home entertainment. Far more elaborate home media centers can be built today (with wire service, cable television, and New York Stock Exchange reports), but they are outside the scope of this article. The home media center requires considerable money (about $12,000) and space (a large room), but if money and space are no problem, technology is ready to satisfy your every whim.

The first section of your home media center would be a video system consisting of a videotape recorder and a wall-sized projection television system. The best videotape recorder is Sony’s new Betamax ($1300), which provides a lot of versatility: you can, for example, watch one channel while recording your favorite show or movie on another channel to play back later. The Betamax uses half-inch videotape cassettes, which can record up to sixty minutes of television per cassette. This part of the Betamax system plugs into an advent 750 VideoBeam ($2500) to project a life-sized color television picture—what you have recorded or whatever happens to be playing on the tube—on a six-foot-diagonal screen. It is television at its finest, even the commercials. (For more details on Betamax and VideoBeam, see “The Screening of America,” TM, June 1976.)

In the sound section of your media center, you should have nothing but the best, and the best in home audio equipment has always been that little old company from Binghamton, New York: McIntosh. There are other excellent audio components on the market today whose performance is on a par with McIntosh, but not one in a field of approximately fifty major companies has the longevity and durability of McIntosh products. For a home media center system, you should have separate components, not a receiver. The amplifier would be the new McIntosh 2205 ($1200), which delivers 200 watts per channel and is absolutely foolproof to operate. The tuner would be McIntosh’s MR 78 ($900)—a unit with the lowest distortion and greatest selectivity today. The preamp is the C-28 ($650), a very flexible unit that will allow you to use up to three tape recorders. Despite all the refinements in this system, it is easy to operate—you can even install it yourself.

You will also need a minimum of four speakers. That’s no problem with the McIntosh 2205 amplifier, which has exceptional power and stability.

Yamaha NS1000M studio monitor speakers would be the best choice, because they have clean, transparent sound and they are capable of handling the massive power output of the Mac amp. Four Yamaha NS1000M speakers will cost you $2000.

The turntable would be Bang & Olufsen’s Beogram 4002 ($750), a cleanly designed electronically sophisticated, straight-line tracking model. You need touch only one control on the 4002 to start the playing process. Platter speed and record-size adjustments are done automatically by a photoelectric cell. To give you “life-performance” musical reproduction at a touch of the button, attach an audio Pulse Model One to the system. For a tape recorder, Nakamichi’s 1000 II ($1450)—a three-head studio-quality cassette recorder—will more than suit your needs.

The important point of this home media center system is its overall simplicity. Every component (there are twelve) is relatively easy to operate, requiring not much more technical knowledge than it takes to run a clock radio. In sum, folks, the future is now, and it’s in boxes on shelves in a stereo or electronics store near you. Enjoy the future shock.

A Little Goes a Long Way: Best Small Spaces System

“One man’s ceiling is another man’s floor,” says the song, and nowhere is this fact more apparent than in a living space like a dorm room, a studio apartment, or just a single room in a big old house that you’re sharing with ten of your impecunious friends. Fitting a high-performance stereo system into a constricted area is tough. Finding the money to do it on an equally constricted budget can be even tougher. Fret no more. You are about to be rescued.

As mentioned earlier, stereo equipment is getting smaller and less expensive (although you can still drop megabucks on a state-of-the-art system). Both trends work to the advantage of the young consumer, because now, more than ever, you get more performance for your money when you buy a lower-priced stereo system.

As with all things in nature, a certain balance must be struck between a small room and the ideal stereo setup. A system that is too large will take up too much space. A system that has too much power will be inadequately employed in a small room. A system that is too delicate is too easily abused in cramped quarters. A good system for a limited space should be small, inexpensive, simple to operate, and tough.

The best small-space system consists of a Pioneer SX 450 receiver, a B-I-C 940 turntable with Ortofon VMS20E cartridge, and a pair of speakers (Advent 3, Bose 301, or ADS 100). This setup sounds like a mouthful but it plays like a dream.

Taken one by one, the individual components are formidable. Pioneer’s SX 450 ($200) is a small, easy-to-operate receiver that has many of the features found in larger receivers at a fraction of the cost. It delivers 15 watts per channel, looks nice, is solidly built, and sounds great in small rooms. Mate the Pioneer with a pair of Bose 301 speakers ($100 each). Little brothers of Bose’s popular 901 speaker system, these speakers put out both direct and reflected sound. If your room doesn’t have a configuration suitable for the Bose speakers (the direct/reflected design requires that they be placed close to a wall or a corner) get a pair of ADS 100s; they are small but exceptionally accurate. I think they sound better than the Bose 301s, but speaker selection is a subjective matter. The Advent 3 ($55) is a fine speaker and compact, too.

A B-I-C 940 ($110), featuring belt drive and with single- and multiple-play capacity, will spin the records for you. You will also need a pair of headphones—a virtual necessity for dorm or shared-house living. Try the ultralight Yamaha HP2s (only $45), designed by aforementioned architect Bellini. Another reasonable choice would be the somewhat heavier Nakamichi HP 100s ($50).

If you have more money, trade up to an Advent Model 300 receiver ($260), a 15-watts-per-channel AM/FM receiver. It is far more portable than the Pioneer, very sophisticated in design, and its musical reproduction is impeccable.

Bands on the Run: Best Portable System

One era’s luxury is another era’s necessity, and this era’s necessity is music. We’ve got to have it—everywhere. In our offices, our living rooms, our bedrooms, and our bathrooms. In elevators. In the car or the back of the van. On airplanes. In boats. In the dentist’s chair. Never in the history of sound reproduction have so many people carried so much music so many places.

In lugging music around in the past, we had two choices—too much equipment (a component system with two speakers, turntable, receiver, and armful of records) or too little (a portable cassette player or radio, either of which does a creditable but not outstanding job of reproducing sound). Friends, there is good news: we have now officially entered the age of superb portable music, and the product that has made this possible is the ADS 2002/Nakamichi 250 system ($700). If the performance of this no-compromises/no-excuses system doesn’t make you a believer, its lofty price tag will. Seven hundred bucks is a lot to pay for a sound system that you can hold in two hands, but in this case you get your money’s worth and then some.

To appreciate why the ADS/Nakamichi system is so hot, it is essential to understand what it is: a component-grade tape deck linked up with two small, studio-quality speakers. The tape cassette part of the system is the Nakamichi 250, a miniature playback-only cassette deck that has been engineered to endure the bounces and jolts of mobile life. The Nakamichi 250 has outstanding performance specifications for any cassette deck, regardless of size, but you’ll also love it for its versatility, accuracy, and ease of operation.

The tape deck is linked, via a single “interface” cable (as they’re called these days) to the ADS 2002 speaker setup, the true high-tech center of the system. The ADS system is composed of two black-satin-finished, solid aluminum speaker cabinets, each of which houses two miniature speaker systems and three amplifiers. Thus there is no need for a separate amplifier—it is all built in—and because of this feature, the amplifiers can be electronically matched to the performance of the speakers. What this means to you is that the ADS speakers, which are about the size of a 59-cent box of Kleenex, sound as accurate as the speakers in your home. The bass performance of the 2002s equals or exceeds that of speakers six to ten times their size. The amount of power available to the speakers is astonishing: 40 watts per channel. In a car, the ADS/Nakamichi system is so powerful, and so fine to listen to, that you will find it hard to believe that anything that sounds so good could be so small.

The entire ADS/Nakamichi system can be disconnected from your car—in a matter of seconds, not minutes—and reassembled in your plane, office, or home. It will even travel with you on commercial airplanes in a case that is small enough to fit under your seat. All this, and great sound too. I nominate the ADS/Nakamichi system as the hi-fi product of the year.

Taking Care of Business: Best Office System

The best office system turns out not to be a system at all—you’d look pretty funny lugging a receiver, pair of loudspeakers, and turntable into your cubicle at Tenneco, wouldn’t you?—but a remarkable FM radio from Advent suited for serious duty in the office.

The Advent Model 400 FM radio was designed to produce high-quality music without a lot of technical hassles or financial hardships for the people who bought it. It is an outgrowth of the consumerist-populist philosophies about stereo espoused by Advent founder (and former chief engineer) Henry Kloss, the man who brought you the wall-sized television. Kloss, one of the original geniuses in the electronics business, reasoned that a lot of people, including office workers, would like to have high-quality music in places where conventional stereo systems wouldn’t work. He turned to his drawing board and produced a design for the Advent 400 FM radio, a two-piece music system that costs $140 and fits just about anywhere. The Advent is a mono FM receiver with a miniature speaker system: you put the control section within easy reach and the speaker section where it sounds best.

Kloss believes that the less there is to get in the way of making music, the better. The advent FM has only four functional controls (on-off/volume, bass, treble, and tuning). It’s as easy to work as your toaster. It also sounds great, which your toaster does not. The Advent FM is small enough to fit in a small office and large enough to fill it with music. Another plus to its performance is its ability to deliver excellent sound at low volumes—a must for any office. It is also versatile—you can hook a cassette machine up to it and record or playback. All these reasons, plus the beauty of its design, have combined to make the Advent FM the Louis Vuitton of radio—anyone who’s anyone wants one.

Going Mobile: Best Automobile System

For far too long, automobile high-fidelity has been riding in the backseat of the car. Anyone in search of true, accurate, worthy-of-a-listen hi-fi has certainly not been looking for it on wheels, because the only things to be found there are constricted AM/FM radios, distorting loudspeakers, cassette players with more hum than harmony, and a host of other acoustic devils, not to mention the dreaded eight-track cartridge player—the biggest electronic monster of them all. It wouldn’t back up, wouldn’t play one song at a time (because of the narrow track width, two songs often play simultaneously), and took up a lot of space. Sold to the automobile companies as the way to listen to music, eight-track was, for quite awhile, the only automobile tape system available. In a like-it-or-do-without situation, the eight-track cartridge player flourished.

Then the cassette arrived, with better performance and better service to the consumer. The cassette has served us well enough, but the time has come for yet another step forward: true car high-fidelity.

At this moment, there are two such systems available for car or van. One we’ve already discussed—the ADS/Nakamichi. The other is the Roadstar RS 2900 ($325). The Roadstar is an in-dash cassette stereo tape player that delivers 16-watts output (8 watts per channel) with less than 2 per cent distortion. The distortion figure, not the power output, is what makes the Roadstar an outstanding car system, because anything over 3 per cent is audible and hence undesirable.

There are some other nice touches to the Roadstar besides the snappy performance. It has auto-reverse, which means the machine automatically reverses the tape; you don’t have to touch a dial. There are five push buttons that can be preset for AM and FM (stereo) stations, giving a total of ten different radio settings. The tape transport will fast-forward or fast-reverse your cassette at the touch of a button. Tape indication lights (this culture loves blinking lights) show tape travel direction. There is also an FM noise suppression circuit so that you won’t get static with your Stravinsky, and an FM stereo indicator light. Nice little unit, the Roadstar, and it’s designed for in-dash mounting, which makes it a little more difficult to rip off than one of those units that hang under the dash. Pair the RS 2900 with a couple of Jensen speakers—the C9729 at $45 a pair—and you’re off to the races.

Electronics Intelligencer: What’s New in Sound

The last twelve months have been a banner year for hi-fi equipment. Here’s some information you’ll want to know, put in language you can understand without having it translated by a stereo salesman.

The Bang & Olufsen 4002 straight-line tracking turntable is probably the finest built today, but the $750 price tag may put it out of your reach. In middle-priced turntables, the hottest hand in the business in the last two years has been a company called B-I-C. B-I-C manufactures a line of turntables that use low-rpm motors to cut out unnecessary wow and flutter. The latest is the Electronic Drive 1000 ($280); it comes equipped, by the way, with built-in remote control circuitry so when that option becomes available you can easily adapt your machine.

Dual, formerly the big name in turntables, continues to turn out well-engineered products. Its newest model is the Dual 1249 ($300, without cartridge), a single- and multiple-play belt-drive turntable that has automatic stop and start. Another respected European company, Philips, offers the GA 212 ($170, without cartridge), a highly touted single-play turntable that features electronic controls. A lot of the action in turntable design is happening in Japan, where Sony, Pioneer, and Technics are all turning out “industrial look” turntables that have heavy, cast-aluminum bases and large, massive platters. For about $200 you can have your pick of the Sony PS 3300, Pioneer PL 510, or Technics SL 120. All are direct-drive and so close in quality of performance that only an audiophile would be able to tell the difference.

Front loading—more desirable because it’s more convenient—is the news in tape cassettes today. Of special interest are the Yamaha TC511S ($260), Teac A400 ($330), Technics RS630US ($250), Kenwood XX620 ($220), and Nakamichi 600 ($500). Most decks now allow for unattended taping, which means the machine will record an FM show while you’re out.

The biggest enticement in cassette systems is the Elcaset. Sony, a major cassette deck manufacturer, Panasonic, and Teac have combined technology to produce a new audio cassette system that uses quarter-inch-wide tape in a cartridge about the size of the old eight-track models. The Elcaset is intended to replace reel-to-reel decks operating at 7½ inches per second (the Elcaset operates at 3¾ ips). It has four audio tracks, plus two “control” tracks, on the tape. These control tracks can be used to perform such tasks as synchronizing audio pulses to operate slide shows. Sony has limited U.S. distribution of two decks, the EL 5 ($630) the EL 7 ($900). The cassettes are priced at $7 to $10 each.

The successful introduction of the Elcaset over the next few months could spell the end for reel-to-reel decks as home taping systems. Reel-to-reel has, for quite some time now, become increasingly sophisticated and its new use is as a small home recording studio for musicians or others interested in recording their own voices. Eventually the convenience of the cassette is going to drive reel-to-reel equipment into a market that’s strictly professional or semiprofessional. Just because the Elcaset is coming out is no reason to abandon the audio cassette. It will remain a standard of the industry for years to come for one simple reason: everyone is already geared up for it.

Speakers are smaller this year. The Advent 3 ($55) and the ADS 100 ($100) are two premium pieces in a very good year for speakers. Bose has revised their popular and highly acclaimed 901 and produced the 901 Series III, a design that features a new cabinet and new efficiency. These Bose 901s ($750 a pair) can be driven effectively with amplifiers putting out as little as 15 watts. The old Bose 901s weren’t satisfied with anything less than 50 watts per channel.

JBL, the studio monitor kings, have revised their popular L100 speakers ($650 a pair) by adding a new tweeter. This accurate, high-efficiency speaker is still an American favorite.

B-I-C Venturi has a new speaker, the Formula 7 studio monitor ($450 each), that “thinks.” It is equipped with circuitry that can take audio measurements, automatically adjust the speakers for optimum low-volume performance, and prevent damage through overload.

Pioneer, the largest manufacturer of hi-fi components in the world, has now turned its hand to speaker design. Its HPM 100 speaker ($300) uses a high-polymer molecular film in the tweeter to deliver clearer, high-frequency sounds. It’s a good loudspeaker, but in its price range it faces pretty stiff competition from companies like JBL, Yamaha (their studio monitor NS1000M at $500 each is widely recognized as one of the best designs on the market today), Bose, and Advent. If you’re shopping for speakers, you might want to start with the latest offerings from Bose, Advent, AR, Jensen, Yamaha, JBL, ADS, or Pioneer.

More performance for fewer dollars is the story in electronics this year. Technics, Kenwood, Advent, Pioneer, Sansui, JVC, Hitachi, and Craig all offer fine, low-cost units at well under $300. As an example of what you can get for $170, the Technics SA5060 will deliver 12-watts RMS, with less than 1 per cent distortion. For your money, you also get a seven-stage FM low-frequency circuit (for better reception and less distortion). At the other end of the scale, Kenwood’s massive KR 9400 receiver ($750) puts independent power supplies behind each channel and delivers 160 watts each. The Kenwood looks very authoritative in its gleaming steel case with laboratory rack mounting handles on the front.

Pioneer has a super new receiver, the Pioneer SX 1250 ($900), another 160 watts per channel behemoth that has exceptionally good performance figures in addition to sounding impressive on a wide variety of material.

Another interesting piece of electronic gear is the Bang & Olufsen Beogram 1900 receiver ($325). The Beogram uses heat-sensitive switches to activate the volume, tuning, bass, treble, and balance controls. Just touch your hand to the marked spot and the adjustment is automatically made. Frequently used controls are hidden under the top deck.

Best new product of the year is Sennheiser’s SX424 headphone system. Why? It’s wireless. Information is relayed to the headphones by an infrared beam that’s diffused through the listening area, which means you can move around the room without tripping over wires. The line forms on the right.

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Longreads