Driving through Sugar Land, the suburb of 90,000 half an hour southwest of Houston, you can see the signs of growth everywhere. There’s the Smart Financial Centre, a $90 million, 6,400-seat concert venue that will celebrate its grand opening this month with a stand-up set by Jerry Seinfeld. Next door is the University of Houston’s Sugar Land campus, which will soon break ground on a 150,000-square-foot classroom building. The past decade has brought a new terminal for the city’s regional airport, a $37 million stadium for the city’s Minor League Baseball team, and an outpost of the Houston Museum of Natural Science, complete with its own T. rex. In 2014 Money magazine named Sugar Land the best small city in America to find a job, noting the number of Fortune 500 companies with a major presence there.

But hidden amid this prosperity is a reminder of a forgotten past. Off U.S. 90, behind a bustling shopping center, is a small cemetery surrounded by two concentric rings of chain-link fence. Inside are several dozen crumbling headstones, inscribed with the names and prison numbers of the convicts who died working the sugar plantations that gave the city its name. Most of the convicts died young. Will Stewart, number 50201, died in 1924, at the age of 30. Fred Carson, number 29760, died in 1917, at the age of 28.

The Old Imperial Farm Cemetery has been preserved thanks largely to the efforts of one person, 57-year-old Reginald Moore, a hulking giant of a man who played left guard at Yates High School, in Houston’s Third Ward, and at what was then called the University of Southwestern Louisiana. Now living in an unincorporated area of Harris County just outside Sugar Land, Moore has spent much of the past two decades on a one-man guerrilla campaign to force city officials to commemorate the convict-leasing system that flourished here in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. “They’re trying to hide it,” Moore recently told me. “They’ve done everything they could to run me off, to keep me out of the cemetery. And they’re still fighting me.”

Moore first became interested in the subject while working a brief stint as a prison guard over thirty years ago. In 1985, during the oil bust that crippled Houston’s economy, he was laid off from his job as a longshoreman at the Houston Ship Channel. Desperate for work, he became a guard at the Jester State Prison Farm, in Richmond. It was a period of dramatic upheaval for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, which was then known as the Texas Department of Corrections. Five years earlier, as a result of a lawsuit against the state by a group of prisoners, a federal district judge had ordered the TDC to reduce overcrowding, provide better medical services, and hire more black and Hispanic guards. Moore, who is black, was one of the first beneficiaries of that court order. He arrived to find a prison that seemed stuck in the nineteenth century, with mostly black convicts working the fields under the eyes of shotgun-toting white men on horseback.

“It reminded me of a plantation, the way the guards treated the inmates,” Moore recalled. “You could see and feel the oppression. Even before I learned the history, I felt it.” Moore’s arrival at what is widely referred to as the Jester Unit coincided with the beginning of the crack-cocaine epidemic, and he had a front-row seat to the effects of the war on drugs. “I saw the prison population blossom and bloom,” Moore said. “I saw guys in the community go to prison, get out, then go right back in, because if you had just a little pebble [of crack] you went to jail.”

Disturbed by what he was seeing, Moore began researching the history of the Jester Unit. He learned that it sat on land that was part of the 97,400-acre tract granted by the Mexican government to Stephen F. Austin in 1823 for his services as impresario. Like most of the Anglo settlers he brought to what was then northern Mexico, Austin was a Southerner, and he saw Texas as fertile ground for creating the kind of cotton plantations that were flourishing across the South. In his recent book Seeds of Empire, University of North Texas historian Andrew Torget writes that “the rapid movement of U.S. expatriates into northern Mexico was—more than anything—a continuation of the endless search by Americans during those years for the best cotton lands along North America’s rich Gulf Coast.” Integral to cotton farming was slavery, which Austin encouraged by granting settlers 80 acres of extra land for each slave they brought with them.

Texas would become one of the biggest cotton-producing regions in North America, but it was a different commodity—sugar—that transformed the fertile banks of the Lower Brazos. In 1838 three brothers, Matthew, Samuel, and Nathaniel Williams, started one of the first sugar plantations in Texas on property in what is now Sugar Land that had been granted to their family by Austin himself. By the 1850s, sugar was a major industry in Fort Bend, Matagorda, Wharton, and Brazoria counties, which became known as the Sugar Bowl of Texas.

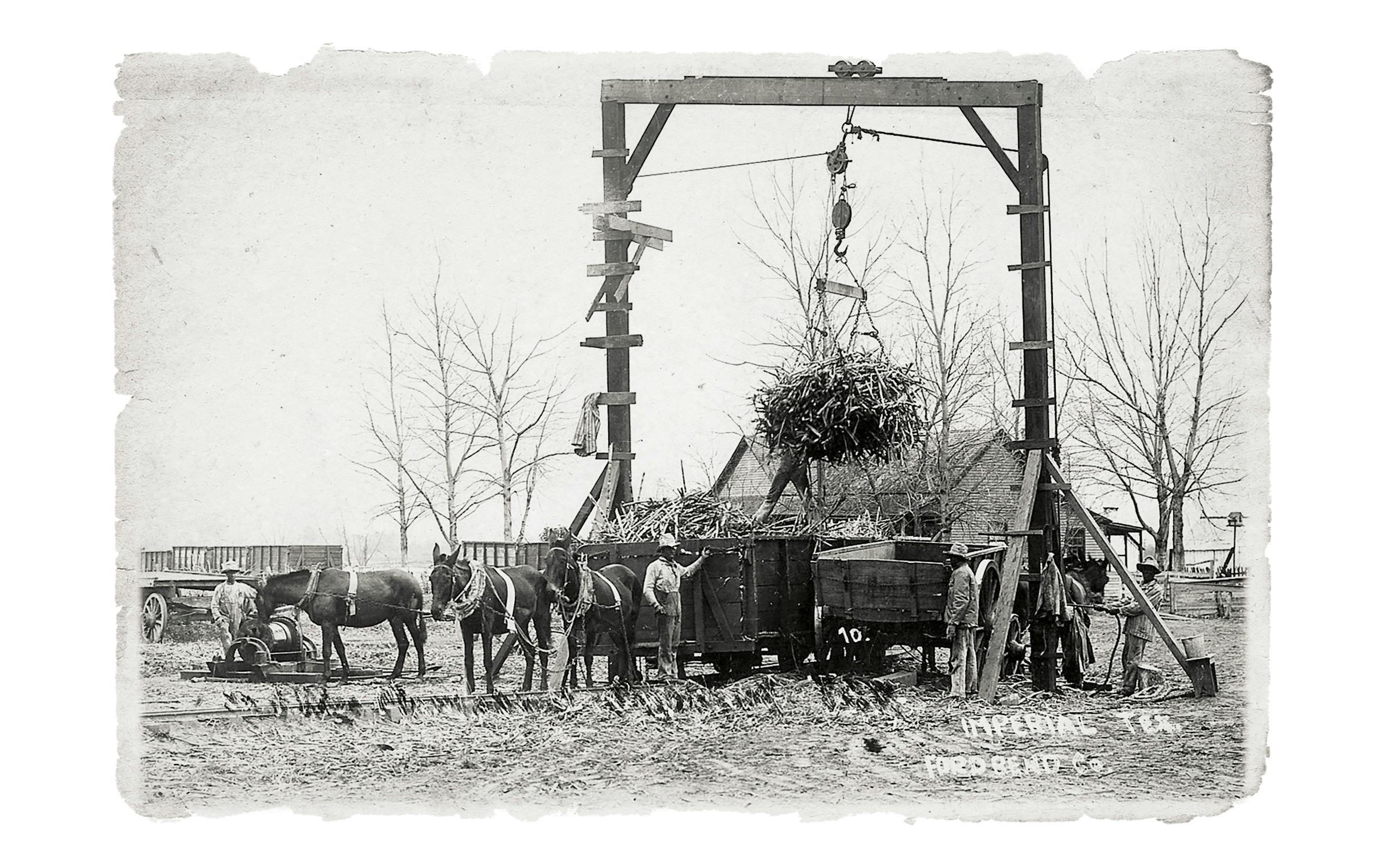

Like cotton plantations, sugarcane plantations relied heavily on slave labor. Harvesting cane was even more arduous than picking cotton. Slaves worked around the clock during harvest season to cut the sugarcane, press out the cane juice, boil it down, and then pack the finished product onto trains to be shipped around the country. “Sugar work was about as bad as you can imagine,” said Sean Kelley, a historian of early American history at the University of Essex. “People got sick, they died. Women’s fertility rates plummeted. Europeans quickly discovered that you couldn’t get people to work in this voluntarily, which is why there’s a strong historical linkage between sugar and slavery.”

Then came the Civil War. The South’s defeat and the abolition of slavery plunged the Texas economy into a depression. Deprived of their labor force, most of the sugar plantations on the Lower Brazos went bankrupt. One of the few that survived was the Williams plantation, which was purchased after the war by Edward H. Cunningham and Littleberry A. Ellis, business partners and Confederate veterans.

Cunningham and Ellis survived the abolition of slavery by finding a new source of cheap labor: the Texas prison system. Although they weren’t the first growers to use convict labor, they were the biggest: in 1878 they signed a contract with the state to lease Texas’s entire prison population. This was perfectly legal, since the Thirteenth Amendment, which outlawed slavery, made one very consequential exception: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” (Italics added.)

In the years before the Civil War, Texas’s state prisons had held around two hundred inmates, all kept at a single facility, in Huntsville. After abolition, the prison population exploded, disproportionately with black men. Unable to house and feed all the new prisoners, the state began renting them out to private companies, who were grateful for the supply of cheap labor.

As he learned more about this history, Moore began to see a parallel between the laws that were used to unjustly incarcerate freed blacks after the Civil War and the laws that were being used in the war on drugs to incarcerate blacks. He visited library archives in Houston and Galveston to look at so-called travel cards, which prisons used to keep track of inmates after the Civil War. “I would read those travel cards, and a big proportion of the blacks were in there on cases where they should have been doing probation or paying a fine,” Moore said.

The working conditions in Cunningham and Ellis’s sugar fields were as bad or worse than they had been on the slave plantations. Mosquito-borne epidemics, frequent beatings, and a lack of medical care resulted in a 3 percent annual mortality rate. The plantation soon became notorious across the state as the “Hellhole on the Brazos.”

Between 1906 and 1908 the plantation and its sugar-processing operations were bought up by Isaac H. Kempner, of Galveston, and William T. Eldridge, of Eagle Lake, who formally incorporated as the Imperial Sugar Company. Although Eldridge had used convict labor on another farm, Kempner was opposed to the practice and began planning to transition to free labor. To attract a new labor force, the two men established a company town, Sugar Land, with worker housing, stores, and a modern hospital.

Texas’s experiment with convict leasing was coming to an end anyway. In 1910, following a series of newspaper investigations of the Texas prison system, the Legislature formally ended the practice; by 1914 all prisoners were back under the exclusive control of the state. From then on, the only entity that would benefit from the coerced labor of prisoners would be the Texas Department of Corrections.

By 1988 the Texas economy was finally coming out of recession, allowing Moore to quit the Jester Unit and return to his longshoreman job. But his three years as a guard had made a profound impression on him, and when he retired, in the late nineties, he decided to devote himself full-time to exposing the hidden history of the Texas criminal justice system. In 2006 he founded the Texas Slave Descendants Society, which advocates for greater recognition of the state’s history of exploiting black labor. He’s focused his activism on Sugar Land because of Cunningham and Ellis’s role in pioneering the convict-lease system.

References to Sugar Land’s early history are everywhere in the city today, from the antique vat used for boiling sugarcane displayed in the courtyard of the local Marriott to streets named after Williams, Cunningham, Ellis, Kempner, and Eldridge. A dramatic sculpture of Stephen F. Austin on horseback, clutching a rifle, stands guard in front of city hall. Even the names of the city’s McMansion-packed subdivisions—Plantation Colony, Plantation Bend, First Colony—evoke a gauzy, romanticized history.

Almost totally missing from the city’s historical memory, Moore realized, is any trace of the slave and convict labor that made the area’s sugar plantations so profitable. The history on the official city website makes no mention of slavery or convict leasing. Neither does the small historical exhibition on display at the Sugar Land Heritage Foundation. (Later this year the Heritage Foundation plans to open a larger exhibition space that it says will address both subjects.) In 2009 Sugar Land commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of its official incorporation as a town by commissioning a volume from Arcadia Publishing’s popular Images of America series. The introduction celebrates a city “built by those with a tenacious spirit that seized opportunity and melded it with a commitment to quality and service to others.” Slavery is not mentioned.

Moore sees a city in denial. One of his first goals as an activist was to preserve the Old Imperial Farm Cemetery, and ten years ago he succeeded in having the small plot officially designated a Historic Texas Cemetery by the Texas Historical Commission. The commission also made him the guardian of the cemetery and gave him permission to conduct archaeological research there. In December a state historical marker was installed at the site. (Moore is not particularly happy with the language on the marker, which he says is a watered-down version of the historical record.)

Moore is not without allies. He’s received support and advice from Rice University history professors W. Caleb McDaniel and Lora Wildenthal, as well as University of Houston anthropologist Kenneth L. Brown. In 2015, Rice’s Woodson Research Center acquired Moore’s archive of historical research and mounted an exhibition about convict leasing at the university library.

“I was very interested in the stuff that Reginald had pulled together,” said Wildenthal. “Convict leasing is the missing link between slavery, which everyone knows about, and the disparate impact of the criminal justice system on African Americans today.”

Emboldened by his success, Moore lobbied city and state officials to build a memorial to convict laborers next to the cemetery. “They honor Stephen F. Austin and Cunningham and Ellis,” Moore explained to me. “Why can’t they honor the black people who built this town?” Then he increased his demands, arguing that the city needed an entire museum dedicated to slavery and convict leasing. He also began requesting official apologies for the state’s involvement in the convict-lease system. He was ignored or received polite refusals.

Sugar Land officials have grown tired of Moore’s relentless activism. “He has come to the city council and expressed his interest in the city creating a museum for the convict-lease program,” said city manager Allen Bogard. “He’s also asked for reparations from the city, slave reparations.” Some city officials have questioned Moore’s motives. “In the past, he has told us that if we contract with him [to build a memorial or museum] and if we pay him money, he would probably be a whole lot easier to get along with,” said Phil Wagner, the city’s assistant director of economic development. (Moore emphatically denies trying to extort money from the city.)

The city has declined to build a memorial or museum, although it did include a display devoted to the subject at the Houston Museum of Natural Science at Sugar Land, which is housed in a former prison barracks. The way Bogard sees it, the Sugar Land of 2017 has no connection to what happened in 1910 or the 1850s. “There’s not a single facility, road, nor improvement that exists today in the city of Sugar Land that can be traced back to either the convict-lease program or slavery,” he said.

When I mention the Imperial Sugar Company, which is now owned by a European group but maintains an office in town, Bogard again demurred. “Our history as a city begins fifty years ago. The Imperial Sugar Company, of course, played an important part in our early history. But the fact is that this area would have developed with or without the Imperial Sugar Company.”

Just outside Sugar Land is a living memorial to the area’s history: the Jester Unit, where Moore worked in the eighties. Driving along Harlem Road in Richmond, Moore pointed out the vast fields where Texas prisoners still plant and harvest crops. Inmates in white uniforms were visible behind fences topped with razor wire. Moore also spotted the gate leading from the prison out into the fields, where he used to perform guard duty. “I watched the prisoners going out to the fields every day through that gate and coming back in.”

In recent years Texas’s prison population has dropped significantly. Five years ago, the TDCJ closed its first prison in more than a century, the Central Unit, in Sugar Land. The Jester Unit may be next; thanks to Fort Bend County’s explosive growth, the prison sits on valuable land. Several upscale subdivisions have arisen within sight of its walls.

There’s also been a national backlash to prison farms, thanks to the same kind of investigative journalism that killed off convict leasing in the early twentieth century. Just as slavery gave way to convict leasing and convict leasing gave way to state-operated prison farms, the prison farm system now seems to be in decline. What replaces it remains to be seen.

Bogard, the Sugar Land official, sees a bright future for his city, one increasingly untethered to its regrettable past. “Thirty-four percent of our residents are foreign-born, and thirty-eight percent of them are Asian,” he told me, standing in the plaza outside city hall near the town’s much-discussed selfie statue. “We have a population that is less than ten percent African American and has never been a significant part of our recent history since we’ve existed as a city, even though we’ve had black representatives on our city council on two different occasions. So that is a part of our history . . . it’s nothing that ever comes up here, other than that occasionally we have a conversation with Reginald Moore.”

Those conversations seem likely to continue. On a Wednesday morning in October, Moore stepped to the microphone in a conference room at the Hilton Garden Inn West in Katy. Wearing a Martin Luther King Jr. T-shirt, he glared at the members of the Texas Historical Commission, who had gathered for their quarterly meeting. He began by reading an excerpt from a history of the Imperial State Prison Farm that describes convict laborers “dying like flies in the periodic epidemics of fever.”

“A lot of people would like to turn their heads [from] this—but you can’t turn your heads!” Moore told the committee, rapping the lectern loudly with his knuckles to emphasize his point. “I need your support. I need legislation. I need activism. We need to put this in Texas history books. We need a monument put up in the state capitol to those workers who brought our state out of recession when it was devastated by war. Be advocates! Because I’m tired. I’ve been doing this seventeen years.”

The commission members asked Moore a few brief questions. Then they moved on to other business.