Everyone on the Port Arthur waterfront knew there was a blood feud between the Lees and the Fredemans,but when Jimmy Lee started accusing the Fredemans of being crooks and racketeers, folks figured Jimmy was either drunk or crazy. The Fredemans were the most prominent and powerful family in Port Arthur. Jimmy Lee was a reformed drunk and an unrepentant troublemaker, a semiliterate who had spent years aboard various tugboats and midstream fuelers and squandered much of what he made on whiskey and bad judgment.

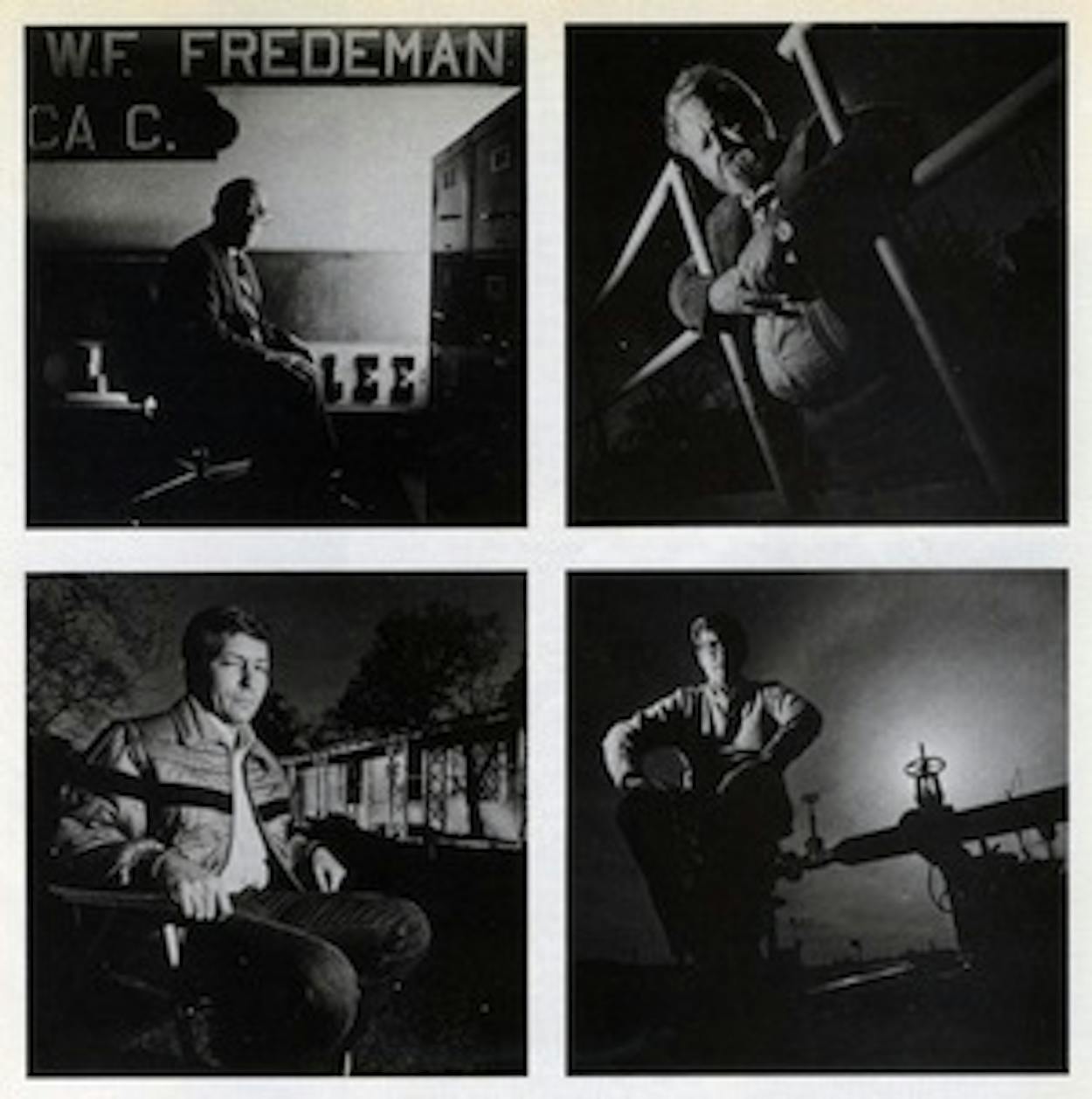

James L. “Jimmy” Lee, Sr., is 54, but he looks older. His skin is as weathered and dark as an old catcher’s mitt. He has big jug ears, a prize turnip for a nose, and a voice that sounds like a muffler dragging on asphalt. What hair he has left is greasy from his lifetime habit of dressing it with baby oil, and his few remaining teeth are decayed and stained by the cigarettes he chain-smokes. He can’t remember what year he dropped out of school—he thinks it was the fifth grade—but at age twelve, like his father and brother before him, he went to work as a deckhand on one of Captain William F. Fredeman’s tugs, pushing cargo along the Gulf Intracoastal Canal and up the Mississippi.

By the time Captain Fredeman stepped aside in 1979 and turned his business over to his two sons, William Junior and Henry, he had built a marine empire with an estimated worth of $100 million. To the public, the Fredemans personified success and respectability, but some people on the waterfront had a different perspective. According to Jimmy Lee, what the Fredemans really were were thieves. Jimmy had been a thief himself, as he freely admitted, not only during the fourteen years he worked for the Fredemans but also later, after he went into business for himself. Jimmy said the Fredemans ran his family out of business on two separate occasions; the Lees couldn’t steal fast enough to keep up with the Fredemans, Jimmy maintained. Jimmy was a proud man, as irascible and tenacious as a junkyard dog, and when he believed that the Fredemans had dealt his family one insult too many, he decided to bring in the law.

Jimmy Lee filed a lawsuit in January 1983, charging the Fredemans with violations of federal antitrust laws. The suit was later amended to include alleged violations of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act (RICO). Specifically, the Fredemans were accused of stealing tens of millions of gallons of diesel from their customers and their suppliers; of bribing employees of customers and suppliers to obtain business or to keep quiet about the stealing; of defrauding customers, including the Department of Defense; and of using illicit profits from those activities to run competitors out of business.

The Fredemans denied all of Jimmy Lee’s allegations and filed a countersuit accusing the Lees and others of practically the same crimes—theft, bribery, and fraud. Since the plaintiffs themselves were racketeers, the Fredemans contended, they could not sue under RICO. The Lees’ financial problems were caused not by the Fredemans, the countersuit alleged, but by the Lees’ own shoddy management.

In November 1983, nine months after Jimmy Lee filed his original suit, the Fredemans filed a motion to dismiss and for summary judgment. They contended that Jimmy Lee’s suit was a sham. The court did not agree. After reading the allegations, counterallegations, and evidence developed through subpoenaed documents, federal judge Robert Parker denied the motion and ordered that the entire matter be turned over to a federal grand jury. It turned out that the FBI had been investigating allegations of theft and corruption on the waterfront since 1980, but that investigation greatly intensified after Jimmy Lee filed his lawsuit.

The allegations in this story are taken from documents filed in connection with that and related lawsuits and from my own interviews with those who were willing to talk.

The two lawsuits were settled and complaints dropped in January 1986; both sides declined to reveal the terms of the settlements. But the legal machinery put in motion by the suits had generated a life of its own, and the federal investigation has continued a hot pursuit that could cost both sides millions of dollars and years in prison. Jimmy Lee doesn’t mind. He says that he will happily go to prison for his crimes —as long as he can look across to the next cell and wave good morning to the Fredemans.

THE SKIPPER OF ANY TUGBOAT IS referred to as the captain, but in Port Arthur the privilege of being addressed as captain is rightly reserved for those who have earned shipmaster papers and commanded oceangoing vessels. William F. Fredeman, Sr., was a genuine sea captain and had been since 1922.

Around the Port Arthur waterfront they called him Cap, and the title resounded with respect. William Fredeman was a big, rawboned man when he first got into the towing business. He is 89 now, frail and so senile that he couldn’t testify in the legal proceedings that threatened to destroy his life’s work, but back then he moved in the manner of a man who knew exactly what he wanted and how to get it.

The son of a stern, disciplinarian father, Fredeman ran away from home in Plattsburg, New York, at sixteen and signed aboard a coal schooner. In World War I he was quartermaster aboard a troop carrier that was torpedoed and sunk off the coast of France. After the war he went to sea for Texaco, earning his master’s papers, and in the late twenties Texaco promoted him to master of ships. In 1933 Texas governor Miriam “Ma” Ferguson appointed Fredeman to a position as state bar pilot in the Sabine-Neches Waterway, a prize for any seaman in those years. Bar pilots, who steered ships up and down the narrow channel, earned about $1500 a month, three times the wages of a sea captain.

At the end of World War II, Cap Fredeman went into business for himself. He bought a used shrimp boat, which he converted to a towboat. In the argot of the inland boatman, a tugboat and a towboat are the same thing, though technically a tugboat has a pointed bow and is designed for ocean travel. Towboats, which is what you see on the Intracoastal Canal, are misnamed: they don’t tow barges; they push them from behind.

Port Arthur was one of the busiest ports in the country in the forties, second only to New York in tonnage. It was the geographic center of America’s refining industry, a major exporter of oil products until the sixties, when oil discoveries in the Middle East changed the world market. But exporting oil aboard oceangoing vessels was only part of the picture, as Cap Fredeman recognized when he started what became Port Arthur Towing Company (PATCO) with his converted shrimp boat. Port Arthur is also centrally located on the Gulf Intracoastal Canal, which stretches from Brownsville to North Florida, with access to the Mississippi and other rivers. Thousands of tugboats pushing tens of thousands of barges loaded with oil, grain, steel, cotton, and other products used the waterways the same way trucks used the interstate highways.

Port Arthur was a rough, rowdy, often corrupt town in those days. Gambling dens and whorehouses ran wide open until the sixties. Authorities at the time described activities in Jefferson County as “the oldest, largest, and best organized vice operation in Texas.” The town was naughty but exhilarating. In the swank Port Arthur Club, on the top floor of the grand and gaudy Goodhue Hotel, wildcatters and sea captains hobnobbed with gamblers and bootleggers.

Today the Goodhue is boarded up and rotting, and so is almost everything else in downtown Port Arthur. The only signs and sounds of life are the neon shimmer of a Vietnamese shrimpers’ bar and the echo of a teller’s voice at the drive-in bank. The real skyline of Port Arthur is a complex of refineries belching gray clouds of smoke.

Port Arthur has always been a pragmatic, blue-collar town, the sort of place where people go out of their way to celebrate an industry that turned their town into a cancer zone. The town put its eggs in one basket, a very big basket owned by Gulf and Texaco. The refineries made the town, created it and manipulated it for years, and when the changes came, as they always came, the refineries dismissed the town with a shrug. Texaco laid off 2850, Gulf reduced its staff by 600, and another 4000 were laid off in related industries. You can see its spent grandeur along the waterfront. In an arm of the old ship channel, hidden like a graveyard, five freighters and three tankers sit dead in the water, their paint flaking and peeling and their smokestacks covered against rain: some of them have been there two years or longer, waiting for work. A small fleet of oceangoing tugs that once towed mighty offshore drilling platforms are huddled now like starving beggars.

For the Fredemans the wealth generated by the success of PATCO was not simply its own reward. They used their money and their tenacity to create an important place for themselves in Port Arthur society. In the early years Cap Fredeman ran PATCO from his English-style cottage east of downtown. His wife, Sydalise, secretary-treasurer of PATCO, taught Sunday school and raised their four children. Cap used to love to tell his sons, Bill Junior, the oldest, and Henry, how the captain of a coal schooner had fired him because, though he was a hard worker, he ate too much. He loved recounting too how he had survived a bitterly cold New York winter in a ten-cents-a-night flophouse—it was called a flophouse because guests paid for a straight-backed chair and slept with their heads flopped over a line of rope strung between two posts. “He never forgot the hard lessons of his youth,” recalled John Palmer, who grew up with Henry Fredeman and later worked for the Fredemans. “He used to tell us, ‘The only real son of a bitches in the world are those bastards who are broke.’”

Sydalise Fredeman was a persistent, strong-willed woman fifteen years younger than her husband. Born to a poor family in the bayous of Louisiana, she was three when her mother died, and she remembered spending her childhood in the cornfield astride her father’s plow horse. Her father moved the family to Port Arthur when he went to work in the refineries. During the Depression, Sydalise had to leave Port Arthur College for a job at a downtown drugstore. That’s where she met Cap Fredeman.

In the late fifties the Fredemans bought a home in the silk-stocking section of Port Arthur. The house is at 221 Dryden Place, one of the semiprivate streets that dead-end into the seawall east of downtown. Back then, almost every prominent family in town lived in that neighborhood. Judge J. W. Williams, an attorney who achieved legendary status by rushing to the gusher at Spindletop and chaining his desk to an oak tree while he wrote oil leases, lived two houses down from the Fredemans.

Once, there had been a levee along the waterfront with a road that followed the ship channel and clusters of white and red oleanders, but the good, practical people replaced most of it with a gray concrete seawall. Today the Fredemans and the other prominent people who live on the semiprivate streets can walk to the curb if they are so inclined and enjoy the view of the top of a ship’s smokestack, sliding by silently on its way across the world.

As the Fredemans prospered and their wealth became the raw material of legend, Sydalise ascended to grande dame of Port Arthur society: eleven years as Sunday school superintendent of the United Methodist Temple, four sessions as PTA president, the first woman to serve as president of the Red Cross, the YMCA, and United Community Services. A compilation in the Port Arthur News in 1977 credited her with organizing six city drives, belonging to 29 clubs and groups, being appointed to 61 boards, and receiving 37 special honors and awards. Her press clippings were dutifully pasted in scrapbooks that filled an upstairs closet and were sometimes displayed on the dining room table in a public declaration of worth and power.

For all of her honors and accolades, Sydalise retained much of the stubborn, pious, practical residue common to the community. If it was Sunday, you could always find her in the balcony of the United Methodist Temple. Like Cap, she didn’t drink, smoke, or gamble. The desire for respectability seemed to govern her life. She told an interviewer from the Port Arthur News that her husband went to sea for advancement, not out of any love for the sea. And yet she could be almost maudlin about her heritage. When the Fredemans donated $10,000 toward the purchase of a new organ at the United Methodist Temple, the Reverend Roger Shuemate sang “Old Man River” and dedicated it to the Fredeman family. Sydalise was so moved by the rendition that she stood up and donated another $10,000. “We’re such river people,” she told admirers later.

AMONG CAP FREDEMAN’S FIRST crewmen were members of the Lee family. By the age of sixteen Jimmy Lee was captain of the Fredeman tug, Ila May. In those days crews worked 30 days on and 5 days off, although Jimmy could remember times when he was aboard a tug for 65 days at a stretch, pushing cargo from Brownsville to New Orleans and sometimes as far away as St. Louis.

There were no showers or toilets and of course no air conditioning aboard forties’ tugs. The only times crewmen set foot on land were when they docked to refill their fuel tanks and to get fresh water. Refueling was a hard, time-consuming process, requiring the crew to moor its barges. Even under ideal conditions, a tow lost six or seven hours each time it needed fuel. Midstream fuelers, which are nothing more than floating service stations, changed all that.

When Cap Fredeman got into the towing business, diesel fuel was selling for pennies a gallon. Old-time boatmen recall that some tugboat operators stole fuel from the barges they pushed along the canal, but that was small change. Thirty dollars’ worth of diesel would run an eighty-horsepower tug for a week or longer. With the creation of the midstream fueling business, petty larceny moved swiftly toward grand theft.

Cap opened one of the first midstream fueling operations on the Intracoastal Waterway in 1957, Channel Marine Fueling Service. It consisted of a small tug called the Leo, a six-thousand-barrel barge called PATCO 21, and a Gulf distributorship. Gulf furnished the fuel, billed the customers, and paid Channel three fourths of a cent on each gallon it sold.

Final pretrial contentions filed by Jimmy Lee’s lawyers in the lawsuit alleged that Cap Fredeman quickly found a way to turn pennies into dollars, primarily by playing on the knowledge that tugboat crews were frequently bored and open to suggestions of larceny: “Captain Fredeman figured out that if you could break the monotony of the lives of the people on the boat, they might do you a favor, such as letting you steal from their boss. The Captain provided entertainment. He gave lonely crew members whiskey, tobacco, and loose women. It became standard practice that whenever you did business with Channel, you would get those kinds of gifts.”

Ports were the marine equivalents of border towns, places where almost anything—or anybody—could be bought. The economy of the waterfront functioned on the practical presumptions that (1) the product belonged to someone else anyway and (2) nearly everybody did it. Even today you can hear deals being made on the marine radio all the time—some tugboat captain agreeing to give some shrimper $500 worth of diesel fuel for a $70 basket of shrimp. Diesel fuel has long been the coin of this realm; every boat that moves along the hundreds of miles of Intracoastal Canal and up the rivers of America operates on diesel fuel, and once the fuel is stolen it is impossible to trace and easy to sell.

Petroleum is a nebulous product. You can’t put a serial number on it, and it is always subject to temperature changes and gauging techniques. With the exception of midstream fuelers, meters are hardly ever used for marine fuel exchanges. Fuel transfers are gauged by hand, by professional gaugers using long poles and conversion tables called strappings. A gauging error of three quarters of an inch might translate to 70,000 or 80,000 gallons—or dollars.

“No one reports it because no one wants to open up their own books to investigators,” Captain R. J. Underhill told me. Underhill, a shipmaster and former tanker captain who also consults for shippers and investigates the theft of cargoes, estimates that oil companies lose through theft an average of 1.2 per cent of all cargoes. Underhill cited the example of a major oil importer that skimmed one tenth of one per cent off each shipload. Over a year, one tenth of one per cent totaled $30 million.

Jimmy Lee himself came up with one method of defrauding Gulf. He called it the rocking-chair barge. Gulf had no way of measuring how much fuel was being pumped out of its storage tanks; it charged according to how much was pumped into the barge. The barges were measured when they arrived and again when they departed the docks.

An analysis of Jimmy Lee’s lawsuit, filed in a related lawsuit, details how the scam was executed: “…the trim tank on the stern end of the barge would be filled, giving the barge about a two-foot drag. Prior to filling the barge at the refinery, it was gauged at the stern where all of the fluid accumulated, causing the gauge reading to indicate a higher level of fuel than was actually there. When the barge was loaded with fuel it was loaded by the ‘head’. After loading the fuel all of the fuel would move forward towards the hatch end of the barge. The effect was to allow Channel Marine Fueling Company to receive more fuel from Gulf Oil than Gulf Oil would report.”

Today refinery gaugers use what is known as a trim factor to compensate for the fluid level in the barge, but back in the late fifties a tactic like the rocking-chair barge could skim 40,000 gallons in a 252,000-gallon bargeload, according to Jimmy Lee.

Another method of stealing fuel from Gulf, the document continues, was called short-sticking: “Captain Fredeman created a gauge stick to be used for gauging his barges after they were filled at the Gulf Refinery that was a foot shorter than a standard gauge stick. When the Channel barge was first taken to the refinery to receive fuel, either Mr. Lee or Captain Fredeman would use the standard-length gauge stick to gauge the barge to determine the amount of fuel already in the barge. Then, after the load of diesel fuel had been pumped into the barge, the ‘short stick’ was used to measure the fuel. Thus, by using the ‘short stick’, a fewer number of gallons would appear to have been received by the barge than were actually received.

“Mr. Lee [in his sworn deposition] recounted . . . that he and Captain Fredeman bribed … the Gulf Oil dock employee from five to ten times a month with pocket knives and cartons of cigarettes so that the employee would allow Mr. Lee to gauge the barge himself.”

Cap Fredeman was too senile to testify in the lawsuit, but his oldest son, Bill Fredeman, Jr., denied that Channel ever underdelivered fuel. Bill had joined the family business in 1959, when Jimmy Lee was still general manager, but he wasn’t around when the alleged rocking-chair barge scam took place. He had never even heard the term “short-sticking,” Bill Fredeman testified. Henry Fredeman, who was in law school at the University of Texas when Jimmy Lee was Cap’s general manager, also denied that the company had ever done anything illegal.

Jimmy Lee said he left PATCO because Cap Fredeman refused to pay him a promised percentage of the profits. Jimmy was expecting $16,000—he was already pricing a new home in Groves, a middle-class bedroom community just outside Port Arthur—but he said Cap gave him only $2500. That was when he quit, Jimmy maintained. With his own company he could steal that much in a month. In 1964 Jimmy and his older brother, Raymond, who had also worked for Cap Fredeman as a teenager, opened Lee Marine and later Mobil Fuelers in direct competition with the Fredemans.

Final pretrial contentions filed by the Lees’ attorneys stated that Jimmy and Raymond continued their dishonest practices because that was the way they had learned to do business when they worked for Cap Fredeman’s “tightly organized crime family.”

In 1968 the Fredemans opened a second midstream fueling company. They called the new company Palmer Midstream, after Henry’s longtime friend John Palmer, though Palmer had no ownership interest.

Henry had completed law school in 1965, and after a short hitch in the Marine Corps, he had returned to Port Arthur as legal counsel and vice president of the Fredeman empire. Of the two sons, he was considered to be more like Cap. He was as tall or taller than the old man and so slender that classmates at Port Arthur High called him the Crane. Like Cap, Henry was intense and domineering. Henry eventually took over the fueling operation that was the cornerstone of the business, but until 1979 Cap remained chairman of the board; it was his decision to start Palmer Midstream, which he ran with an iron hand. Meanwhile, older son Bill had been placed in charge of the towing company and a son-in-law, James Crawford, had taken command of the Fredeman Shipyard near the Calcasieu Locks in Carlyss, Louisiana.

All of the Fredemans, as well as James Crawford, refused to be interviewed for this story, but in his deposition Henry Fredeman described how the new fueling company came into being and why it was named Palmer Midstream. According to Henry, Shell Oil was looking for a new distributor to replace another midstreamer that had gone out of business. The midstreamer that had gone out of business had sold its equipment to Raymond Lee. As Henry got the story, Raymond Lee had telephoned Shell and tried to bully it into giving him the contract. Shell decided it would rather do business with the Fredemans, Henry recalled. But there was a problem, as he went on to explain: “At that time we were also operating Channel Marine Fuel Company as a Gulf distributor, and Gulf didn’t want us handling . . . anybody else’s product … so it became necessary to create a new corporation. … I had been getting letters from John Palmer who was in the Army in Korea . . . and he was fixing to get out of the Army and . . . needed a job, so we decided that we would go set up a new corporation, and in order to distinguish it from the Channel Marine Fuel Company we would name it Palmer Midstream Service and let John Palmer run it.”

When I interviewed John Palmer, he gave me a different version of how Palmer Midstream came about and how it operated. First, he never ran the company; he just worked there. Second, he didn’t contact Henry; Henry contacted him. “I had been back from Korea for at least a year and was a captain of a military police company at Fort Sam Houston when I got Henry’s letter,” Palmer told me. “I had about decided to make a career of the military when I got Henry’s letter. He wanted me to be a straw man so they could get the Shell distributorship. I had to take a cut in salary to go to work for the Fredemans, but it was a chance to make big money later.”

Palmer had known the Fredeman family all his life. He and Henry were born the same year, 1940, and had been classmates from kindergarten through high school. After high school Henry went to the University of Texas and Palmer attended Texas A&M, but a year later Palmer transferred to UT, and they were classmates again through undergraduate school and three years of law school. John Palmer thought of Henry Fredeman as his best friend, a boozing and wenching buddy to be sure, but more than that—he thought of Henry as a brother and of Cap Fredeman as a father.

Long before John Palmer joined the company, Jimmy and Raymond Lee said in their depositions, Cap had chased them all over the waterfront. When they tried to dock their two wooden-hulled fuel boats at a site called the Rockpile across from the Gulf Refinery, Cap leased the site from the railroad and had them evicted. The Lees moved next to the city docks near the old Pleasure Pier Bridge, a spot long favored by shrimp boats, but a city official soon appeared and ran them off. In 1964 the Lees leased a dock on the Sabine River in Orange. From 1964 until 1968 business was good for the Lees. Then John Palmer arrived. “I put Jimmy Lee’s ass out of business in no time,” Palmer told me. No matter what price Jimmy put on his fuel, Palmer recalled, Palmer Midstream quoted a sweeter one.

When Jimmy Lee first filed his lawsuit, the Fredemans didn’t seem to be too concerned. Jimmy Lee, who was making most of the accusations, was an admitted crook. So were other members of the Lee family. Lawsuits of such magnitude could cost millions of dollars, and the Lees were already heavily in debt from their failed business ventures. Smart money was betting the Fredemans could win by simply waiting out their accusers. The Fredemans hired a prestigious law firm from Birmingham, Alabama-North, Haskell, Slaughter, Young, and Lewis, and its general commercial litigator, Jay Waller. In August 1983, seven months after the suit was filed, Waller and his colleagues came to Port Arthur to obtain a deposition from John Palmer.

In his deposition Palmer said that his main job was to front for the organization and find new customers. Cap Fredeman told him to be aggressive and to go after business any way he could-even if that meant selling fuel below cost. Palmer was a genuine good ol’ boy, a tough former military police commander who could quote Shakespeare or jaw with the boys on the dock, and he was ready to work around the clock to make the company a success. Shell Oil had predicted that the company would be lucky to sell 500,000 gallons a month after the first year, but in his fourth month at Palmer Midstream, Palmer sold 1.7 million gallons.

In contentions in the final pretrial order, Jimmy Lee’s lawyers picked up the allegations at that point: “The Fredemans wanted the company to be named after John Palmer so that people would think that John Palmer owned the company. Because of the Fredemans’ illegal activities, their fueling operation had gotten a bad name already. John Palmer helped supervise the illegal operations of the Fredemans. . . . Cap and Henry told Palmer to try to short customers by an average of twenty per cent. The Fredemans’ shipyard in Louisiana provided two fuel barges, Midstreamer No. 1 and Midstreamer No. 2, especially engineered for theft.”

Palmer’s testimony proved to be a dramatic turning point in the lawsuit; he substantiated many of Jimmy Lee’s allegations. Palmer testified that Palmer Midstream priced its fuel at low levels — sometimes below cost—to ensure that it would sell large volumes. Jimmy Lee’s lead attorney, Jim Drexler, of the Houston law firm Gillis, Walker, Drexler, and Williamson, inquired why that was.

“A: Well, we wanted to get the business if we could, because we knew if we got the volume, we could make money out of it.

“Q: How were you going to make money out of getting increased volume?

“A: By the fudge factor.

“Q: And what are you referring to, sir, when you say the fudge factor?

“A: Well, we were going to get a certain percentage of all volume that we ran through the meter.

“Q: Could you be a little more specific than that, please, Mr. Palmer? . . .

“A: Well, all meters can be adjusted plus or minus a certain percent. Generally I think it’s about five percent. And we had the meter adjusted to the maximum, and we had a valve to put fuel back into the barge after it went through the meter. . . .

“Q: With this fudge factor at play, what would be the result to a customer who purchased fuel from Palmer Midstream?

“A: He was going to get screwed. . . . A certain percentage of the fuel that he was paying for he wasn’t going to get.

“Q: He was going to be shorted in the amount of fuel that he received?

“A: Yeah.

“Q: Have you ever heard the term ‘hitting’ boats? . . . What does that term mean?

“A: Same thing as fudge factor.”

Though the Fredeman brothers and James Crawford later denied each and every accusation made by John Palmer, that testimony was easily the most devastating to that point. As Palmer (and, later, other former Channel Fueling employees) told it, corruption on the waterfront had acquired its own vocabulary. The fudge factor was also called by another, less elegant, name, utilizing another F-word as a modifier. On the company books the fuel that customers paid for but never received was called overage, which sounded better than its more common name, swag. The valve that Palmer described, the one that returned fuel to the Fredeman barge after the fuel had passed through the meter, was called a hit valve or sometimes a bypass valve. The valves, which Palmer and others said were installed at the family shipyard, were located in the rake, a normally empty space in the after end of a barge. The valves controlled an opening in a three-quarter- inch pipe hidden inside a larger pipe used to support the meter. Once fuel had passed through the meter, a percentage of it was drained back into the cargo tank through the hidden pipe. Palmer said that the established goal for the amount of fuel, to underdeliver was 15 to 20 per cent.

Part of Palmer’s job, the deposition continued, was to field complaints, which occurred almost daily. In his own deposition Henry Fredeman stated that he didn’t remember any complaints, but Palmer said, “Henry was always in the background when it came to complaint time. So I would go to the guy and powder his butt and tell him . . . there must be some mistake . . . your strappings may be off or the boatman may not have been on even keel when he took the strappings . . . we just don’t understand how that happened.” If the complainant persisted, Palmer would adjust the bill.

Palmer Midstream had only two real competitors in the Port Arthur area- Marine Fueling Service, owned by the Bean family, and Mobil Fuelers, owned by Jimmy Lee and his brother Raymond. “Cap hated competitors,” Palmer said.

During the deposition, Henry Fredeman denied each of Palmer’s allegations in crisp, studied, lawyerly tones:

“Q: Mr. Fredeman, to your knowledge has Channel Fueling Service ever operated any of its fuel barges which contained equipment such as bypass lines, and bypass valves which have been installed for the purpose of intentionally underdelivering fuel to Channel’s customers?

“A: Not to my personal knowledge or recollection they haven’t ever done that. . . .

“Q: Mr. Fredeman, are you aware of whether Channel Fueling Service has ever operated fuel barges with meters which have been adjusted intentionally to overstate the amount of fuel being delivered to a customer?

“A: I don’t have any personal knowledge, or any recollection of that ever happening. . . .

“Q: Mr. Fredeman, are you aware of whether Channel Fueling Service has ever, by any method, intentionally underdelivered fuel to its customers?

“A: I have no personal knowledge or recollection of that ever happening.”

Henry said he was aware that the plaintiffs had made allegations along those lines, but he had not personally undertaken any investigation to see whether the allegations were true. Bill Fredeman said he had never investigated the allegations either, but he denied that Channel Fueling or any other PATCO subsidiary had ever billed its customers for more fiiel than it delivered:

“Q: If you don’t know whether it did or not, why are you denying it?

“A: Because my own experience being in the tugboat and barge business would lead me to believe that I have never heard any allegations about Channel Fueling. . . .

“Q: If somebody made such an allegation, what would that lead you to believe?

“A: I really hadn’t thought about it.

“Q: Well, somebody has made an allegation in this lawsuit, right?

“A: That is correct, I guess.

“Q: Could you tell the jury why you have not talked to some of the people who pumped fuel from the fuel barges of Channel to find out whether they did, in fact, deliver the same amount of fuel that they billed for?

“A: No, I can’t.”

In his deposition, Bill Fredeman frequently appeared to be confused. At one point he said that he didn’t know his own salary or how to go about figuring it out. Bill was sure of one thing: he had never heard of a bypass valve until the lawsuit was filed.

James Crawford said that he had no knowledge that the Fredeman shipyard had ever built barges with bypass valves, as Palmer had alleged, nor did he believe it to be true:

“Q: Do you believe that barges containing the bypass equipment that John Palmer testified about could have been built by the shipyard and you not have known about it?

“A: The answer is not very likely.”

Palmer remembered that in the late seventies, as Cap began to think of retirement, the two sons seemed obsessed with the need to show they were better men than their father. The Fredemans’ midstream fueling business had expanded to a dozen locations and was advertising itself as “the largest and fastest-growing midstream fueling service” on the inland waterways. Cap still made an occasional appearance down at the dock, but Henry and general manager Doug Williams began to run the fueling operations, and Bill called the shots at PATCO.

Henry, in particular, seemed driven to prove his worth, Palmer remembered. His old friend had changed drastically since college. Henry’s imperious demands and radical mood changes were a side of him that Palmer hadn’t seen before. It seemed obvious to Palmer that Henry had fallen victim to a disabling sibling rivalry. Palmer quit the fueling business in the early seventies but continued to work for PATCO until 1975. That’s when Henry fired him.

Henry gave as his reason for firing Palmer his belief that his old friend was trying to work a deal to import fuel for his own private operation. Palmer denied that, though he didn’t deny that he was disenchanted with his job at PATCO. But just as Palmer saw an inexplicable change in Henry, so Henry observed that Palmer had become a stranger.

“In the last year or so he worked here,” Henry said in his deposition, “he and I drifted apart. We didn’t associate too much. He kind of kept to himself, and, you know, just didn’t seem like the same person. . . . My personal feeling is he probably was having financial difficulties personally, and wanted more money, and he did something else to try to get it.”

Henry testified that the family dropped the name Palmer Midstream a year or so after Palmer was fired. The new name was Channel Fueling Service. The original company, Channel Marine Fueling Service, which had ostensibly remained in business during the Palmer Midstream tenure, ceased to be at that point.

Although the Fredemans staunchly insisted that John Palmer lied in his deposition, it was no longer possible to maintain that the accusations were limited to a reformed drunk and his family of rogues. In October 1983, two months after Palmer’s deposition, Jay Waller and the law firm of North, Haskell unexpectedly and without explanation ceased to represent the Fredemans. Whether the firm was fired or whether it withdrew voluntarily, no one will say. “It would not be proper for me to comment on that,” Jay Waller told me. His firm was immediately replaced by another, even more influential firm, Patton, Boggs, and Blow of Washington, D.C.

“I still get sick at my stomach thinking about the fuel business,” Palmer told me a few months ago, sitting in the office of Palmer Barge Line, the company he started after he left PATCO. He was a large man with reddish-blond hair, in his early forties now and overweight; but he still looked tough and ready to command an MP company. Palmer Barge Line’s primary business was towing, and he had a perfect location near the fork where the Neches River intersects the canal. He too believed that the Fredemans had damaged his business. Fredemans or no Fredemans, however, times were now tough for nearly everyone on the waterfront. Out the back window of his office, near a docking area constructed of rusted barges, we could see a number of tugboats at anchor, including the Captain John H. Palmer, a 130-foot, 3200-horsepower Mississippi River tug. It had been sitting there for three years and two months. “I stopped making payments on it three years ago,” Palmer said. “I told the bank to come get it, but the bank doesn’t want it either. I’m not sure who owns it now.”

After his midstream fueling business went bust in 1969, Jimmy Lee didn’t waste a lot of time licking his wounds. He moved back to his hometown, Sabine Pass, and bought a restaurant, which he named the Rebel Inn. Over the next several years he started buying cheap property along the waterfront.

Then in 1973 occurred an event that changed the way people lived around the world. In most cases it was for the worse, but in Port Arthur it looked as if the millennium had arrived. When the shock wave of the Arab oil embargo hit Port Arthur late that year, it shook loose some primitive, atavistic response. This wasn’t just another boom like Spindletop or the postwar era; this was an orgy. For years diesel fuel had sold for 8.5 cents to 11 cents a gallon. But in the months that followed the announcement of the embargo, diesel zoomed to 15 cents, then 20 cents, then 35 cents—by 1975, when the government installed price controls, it was fluctuating as high as 50 cents a gallon.

It seemed that everyone was getting rich in Port Arthur. Refineries were churning at capacity, paying anyone who could find the time clock $13 an hour. After the boycott of Iranian oil in 1979, diesel fuel sold for as much as $1.18 a gallon.

If you could sign your name, you could borrow money. A lot of spanking-new tugboats traveled up and down the canal, icons of the boom. Customers stood in line to buy new cars, and developers threw up new suburbs so close to the swamps that people reported alligators in their swimming pools. When the energy crisis hit and the oil companies started looking for places to expand, Jimmy Lee owned sixty acres right on the ship channel. He had bought the land for $250,000. He sold it for $4.5 million.

From that point, he bought a drilling mud company, an ice plant, a shrimp dock and seafood processing plant complex, a hardware store, two grocery stores, and nine helicopters, which he leased to offshore drilling companies. All of his companies were called Rebel, and he expanded the theme by commissioning the casting of two Civil War-type cannons, which were fired during frequent Rebel celebrations on the docks of his new empire.

There was something almost biblical in the grudging response of Sabine Pass to the hometown boy’s returning and making good and in Jimmy Lee’s open defiance of the response. His dream was to make Sabine Pass a company town and to make himself chairman of the board. When the town resisted, Jimmy took it as a sign of petty jealousy. He also led a crusade to save a scrubby patch of grass called Dick Dowling Park, where his grandfather had been caretaker from 1936 to 1945. Today the park is a neatly manicured monument to one of the few Civil War battles fought on Texas soil.

Jimmy Lee was now a rich man-and a sick one. He had started drinking heavily when he opened the Rebel Inn, and it had gotten out of control. The more he drank, the more he brooded about what he saw as the affronts he had suffered at the hands of not only the Fredemans but practically the whole world.

Life for Jimmy Lee grew more rotten with each bottle of whiskey. His wife, Cleo, divorced him, and Jimmy sold almost everything he owned to Raymond for $750,000-a fraction of its worth.

In 1977 Jimmy’s son James L. “J.L.” Lee, Jr., started a new towing company called Union City Barge Line; and two years later, in direct competition with the Fredemans, J.L. opened Union City Fuel Service. Jimmy had tried to talk J.L. out of going head-to-head with the Fredemans’ midstream fueling business, but the boy was too stubborn to listen. “I can outwork them,” he told his dad.

“Maybe you can,” Jimmy said, “but you can’t outsteal them.”

Finally Jimmy had had enough. He converted a shrimp boat into a yacht, called it the Rebel I, and set sail for the Bahamas, where he planned to forget that he had ever heard the name Fredeman. He got as far as Gulfport, Mississippi, where he tied up in the small-craft harbor and stayed drunk for months. In May 1980, following a three-week bender, Jimmy was taken to the hospital by a friend, and after a few false starts, he dried out. His ex-wife joined him in Gulfport and set up housekeeping on the boat. Raymond also moved to Gulfport. Jimmy hasn’t touched a drop since the summer of 1980.

From all appearances, the Fredemans’ well-oiled machine was working as smoothly as ever in the summer of 1980, but appearances were deceiving. Things had worked smoothly when Cap was in charge and the economy was slow and steady; when diesel sold for less than a dime a gallon, it took years to create a fortune. Now that the price of fuel had zoomed up to ten times what it used to be, the Fredeman sons could make millions by skimming a few percentage points of the fuel that they sold.

In August 1980 Henry and Doug Williams, his general manager, met in New Orleans with an important customer, Carl D. Nutter, the head of inland barge traffic for Union Carbide. By courting Nutter, Channel Fuel had managed to land and maintain an extremely lucrative contract handling Carbide’s “redelivery” program. Under the program Carbide purchased fuel from its own sources and paid Channel Fueling to store it in their shore tanks and redeliver it to Carbide-leased boats on the Intracoastal Canal and the Mississippi.

At almost the same time that Henry Fredeman and Doug Williams were talking with Nutter, there was another meeting in Beaumont at which the Fredemans were a main topic of conversation. The FBI was interviewing several former Channel Fueling employees about reports of theft and corruption on the waterfront. One of them was a young man named Bill Slay, who had been the dock manager of Channel’s Port Arthur facility in the mid-seventies and had also worked for the Lees. According to his own later statement, Slay was less than forthcoming with the feds. After the meeting, Slay says, he called Henry and told him what had happened. Henry denies this.

Nevertheless, final pretrial contentions filed by Jimmy Lee’s lawyers alleged, “[Slay] went to see Henry [after he had been contacted by the FBI], Henry convinced Bill to keep quiet and, as a reward for being a good soldier for the Fredeman family, Slay was given a nice desk job right after he met with the FBI.

“On August 8, 1980,” the document continued, “Henry Fredeman dispatched Slay in Jerry Cabbage’s car [Cabbage was the company accountant] to meet with other witnesses and rehearse their story to the FBI. After talking with them, he reported to Henry that they would keep their mouth shut. . . . Henry Fredeman phoned his brother-in-law, Jim Crawford, to get Crawford’s Fredeman Shipyard to remove the bypass valves on the fuel barges. Removal of the bypass valves did a lot to cut down the amount of theft by Channel. The crews had to resort to an operation called ‘big hosing’ which was like the bypass valve operation, only it was done with flexible hoses that could be removed from the barges on a short notice. . . . They also adjusted the meters themselves to overcharge customers.”

Slay said in his deposition that the big- hosing operation brought with it an incentive plan that encouraged crewmen to steal more. The incentive was in the form of a bonus or commission amounting to 3 per cent of the gallons stolen. Henry Fredeman said he had no knowledge or recollection of any such bonuses. If bonuses were paid, he said, they were based on legitimate sales volume.

Though the Fredemans and Crawford denied any knowledge of the 1980 FBI investigation, nobody denies that Channel Fueling records were destroyed in a bonfire that same month, August 1980. The purpose of the bonfire was to burn obsolete records, Henry Fredeman said, but sales invoices were inadvertently destroyed too. “I don’t really know all that much about it,” Henry said in his deposition, “because I wasn’t even in town when it happened.”

Meanwhile, the boom continued to fuel the fantasies of Jimmy’s son J.L. At the peak, J.L. had signed notes for nearly $1.6 million in order to buy four new tugs. The largest and most luxurious was the Union City Texas, an eighty-foot four-decker with twin 900-horsepower engines. It was painted gray and white with red trim, the Union City colors, and the Union City logo graced its elegant smokestack. It had everything except twin foxtails dangling from its mainmast. The Texas was his flagship-a symbol, perhaps, that whereas the father had failed, the son would succeed. It was this splendid tug that was leased to the company’s biggest client, Union Carbide. Among other things, the Texas delivered bargeloads of Carbide fuel to Fredeman docks to be stored for redelivery.

By 1982 the oil boom had become a resounding bust. J.L.’s biggest client, Carbide, was now practically his only client. He was leveraged to his eyeballs and tottering on the brink of bankruptcy, only he didn’t seem to realize it.

“J.L. lived in a kind of dream world,” recalled his younger brother, Mark. “He had no idea what was happening to the business. He had started drinking and was flying all over the country in his new eight-passenger Piper Navajo [which he had dubbed Air Lee\. I don’t think he believed the boom was over.”

Mark Lee had graduated from Stephen F. Austin State University in 1981-he was the first college graduate ever in the Lee family-and had gone to work for Union City the following January. He was bright and levelheaded, and in the months of turmoil that preceded and followed the filing of the lawsuit, he became a stabilizing force for his family. Jimmy Lee had a remarkable memory; he also had a fiery temper and all the finesse of a bull moose. Mark usually walked a few steps behind his dad, much like the guys who follow Reagan around, saying, “What he meant to say was …” Jimmy would start a letter with “Dear Egg-Sucking Scum,” and Mark would scratch out the salutation and write, “Gentlemen.”

After only a few months of working with his brother, Mark realized that the company was in bad shape. Because of the Carbide contract, which paid Union City $60,000 a month, the Texas was making money. But its sister tugs were losing $7000 to $10,000 a month. J.L.’s real problem, though, was his fueling company: as Jimmy had predicted, he couldn’t steal enough to play in that league. Though J.L. acknowledged to me that he was still hitting customers’ boats, he wasn’t hitting them hard enough to stay even, much less reduce the price of fuel five cents a gallon, as the plaintiff’s final pretrial contentions alleged the Fredemans were doing. The only thing that kept J.L. afloat was a cash-flow arrangement with CIT Corporation, a lending entity owned by Manufacturers Hanover of New York. Union City would wire its records of sales to New York, and CIT would wire back 85 per cent of the face value. Customers were supposed to pay Union City within ninety days, and when they paid Union City, Union City would repay CIT with interest—prime plus 3 per cent. The problem was, most of Union City’s customers didn’t pay within ninety days, which didn’t stop the quarterly payments to CIT from coming due. And prime was 16 per cent and rising in the late seventies.

To keep the cash coming, J.L. created a paper pyramid of phony sales. He began kiting invoices—wiring reports of sales that never took place and covering them ninety days later with more phony invoices. By the fall of 1982 the pyramid of credit was out of control, and J.L. was close to a nervous breakdown. On paper Union City was $500,000 in the black, but in reality the company was $785,000 in the red—the difference was the kited invoices, plus the interest on his bank notes.

At that point Mark Lee did the only thing that made any sense—he telephoned Jimmy Lee in Gulfport and told him about the situation in Port Arthur. Jimmy said that he and Raymond would head for Port Arthur straightaway. Although the Lees habitually fought among themselves, they became as tight as a family could get when it came to battles against outsiders.

Jimmy still had credit at Allied Merchants Bank—he had been a member of the board of directors before he started drinking. He borrowed $250,000, which he secured with marine equipment and other personal assets. Raymond borrowed $200,000 from Allied Merchants. The $450,000 was disbursed like this: $25,000 went back to Allied Merchants to service Union City’s current interest debt, $50,000 was transferred to J.L. to finalize the stock transfer, and the remainder went to CIT to pay down the kited invoices. Jimmy and Raymond planned to keep the business alive only long enough to square things with CIT.

Those plans changed a few weeks later, however. In mid-September, the Lees received a frantic telephone call from a Union Carbide office in Charleston, West Virginia. Carbide had discovered that 46,000 gallons of diesel fuel was missing, and it looked to them as if Union City was the culprit.

From that very first phone call, Jimmy Lee smelled a rat. After grilling the crew members of the Union City Texas, he was certain that they had not stolen the fuel. That didn’t necessarily mean that the Fredemans had stolen it, but Jimmy believed they were behind it somehow. The Fredemans knew that the only thing keeping Union City in business was its contract with Union Carbide. Maybe it was just a coincidence that the shortage was discovered at the Fredemans’ dock in Port Arthur, but to Jimmy it was just too neat a coincidence.

A few days later there was a curious telephone conversation between Raymond Lee and Carbide’s manager of inland barge operations, Carl Nutter. Jimmy was away from the office at the time, but Mark Lee taped the conversation, and Jimmy stayed up all that night, sitting in the Union City offices in Port Arthur, smoking, drinking coffee, and playing the tape over and over. The more Jimmy listened to the tape, the more rats he smelled. At first Nutter sounded indignant, determined to get to the bottom of the mystery. Raymond agreed that they should get to the bottom of it. In fact, he demanded that Carbide send investigators to Port Arthur with polygraph machines to give tests to everyone involved in the barge shipment—the Lees, the Fredemans, and the gauger. When Raymond demanded lie detector tests for everyone, the man from Union Carbide became unexpectedly conciliatory. Nutter suggested that this was probably just one of those mistakes where nobody was really at fault and that probably the best thing to do about the missing 46,000 gallons was to forget it.

Early the next morning Jimmy went into action. He called Nutter and recorded the conversation. He sent Mark to Beaumont to buy one hundred shares of Union Carbide stock so that when he telephoned Nutter at the Union Carbide office in Charleston, demanding to know how Nutter could simply dismiss the apparent theft of 46,000 gallons of diesel fuel without even a cursory investigation, he would be speaking as a stockholder. That same day Jimmy also had Mark draft a letter to the board of directors of Union Carbide. “Are our institutional stockholders . . . aware that our transportation division can dismiss a loss of this size without so much as an investigation?” Jimmy demanded to know.

In early October T. W. Thorndike, a special investigator from Carbide, arrived in Port Arthur and started asking hard questions. Jimmy thought that the investigator agreed with his own assessment— that the Fredemans rather than the Lees were the crooks. But he was wrong. The Carbide inquiry eventually concluded that the missing fuel was the result of a “gauging error.”

The Lees’ business was plunging toward rock bottom, and Jimmy was powerless to stop it. “The Fredemans have f—ed us again,” Raymond said. Jimmy was determined to hang on, but Raymond packed his bags and went back to Gulfport. Jimmy had reduced the kited CIT invoices from more than $600,000 to about $167,000, but the only way he could buy more time was to kite more invoices, which, under his personal code of survival, he did immediately.

In December, exactly three months after Jimmy took over the company from J.L., there was another fateful call: an auditor from CIT was scheduled to arrive the next day at the Union City office for a routine review of the books.

Jimmy stayed up all night, walking by himself along the ship channel, wondering what he could say. Every time he looked at J.L.’s fleet of “floating hotels,” his blood pressure soared. He didn’t know who to blame the most, J.L. or the banker who had loaned him the money. Jimmy wasn’t much for remorse, but walking out there in the cold, wet Port Arthur night, he was truly sorry for the life he had misspent, for the ways he had hurt himself and his family. His whole life seemed to focus on this moment, and then he knew what he had to do. “I decided to ’fess up and take my medicine,” he recalled.

First thing the next morning he told the auditor about the kited checks, adding that he had been able to reduce the debt to a mere $167,000. Jimmy half expected a pat on the back; after all, he was not only admitting the deceit, he was engaged in a heroic effort to rectify the situation. The auditor didn’t see it that way. From the horrified expression on the man’s face, Jimmy could see he might as well have been confessing his part in the plot to kidnap the Lindbergh baby.

The auditor dashed for the nearest phone and ordered headquarters to cut off credit to Union City. “He was nearly hysterical,” Mark Lee recalled. “Jimmy kept saying, ‘You should have been here when it was $600,000!’ The guy stayed around a couple of days, trying to come up with a plan to take over our business, and on the third day Jimmy finally threw him out.”

The situation had never appeared more desperate for the Lee family. They had two options—sell out or refinance. Jimmy calculated that they would need about $4 million to pay off all their debts, so he decided to ask for $5 million. He contacted a company in St. Louis, Economy Boat Store, which had been dickering to start a midstream operation in Port Arthur, and he contacted another outfit called Houston Midstream. At the same time Jimmy and Mark began to draft a plan to restructure Union City’s finances, a plan directed at their major creditors.

In drawing up his plan to save the business, Jimmy made what turned out to be a strategic error—he acknowledged that Union City’s troubles stemmed from mismanagement. Though Jimmy did not mention Channel Fueling by name, he wrote a memo stating that Union City intended to improve its financial position by filing suit against a major competitor. Thus the Fredemans’ lawyers later were able to contend that the Lees’ lawsuit was nothing more than a giant extortion attempt.

Next, Jimmy arranged a meeting with Henry Fredeman. Jimmy gave his adversaries this option: buy Union City or get sued. Jimmy couldn’t prove that the Fredemans had Carl Nutter in their pocket, but he thought that he could prove that Channel’s arrangement with Carbide was an unfair trade practice.

The meeting was held in December 1982, in a Thirty-ninth Street condominium that Channel Fueling used for entertaining customers. When Jimmy arrived, Henry was already there, and so was Doug Williams, a big, prematurely gray man nicknamed the Gray Fox. Jimmy stubbed out the cigarette he was smoking and began to play the tape of his conversation with Carl Nutter. He watched the faces of the two men from Channel for traces of betrayal but saw nothing. “I know all about what you bastards done to me on the Carbide deal,” Jimmy said, again hoping for some sign. Still nothing.

Henry Fredeman remembered the moment this way: “[Jimmy Lee] came into the meeting in an obvious state of agitation, indicated that he had been doing some investigations, and that he had a lot of information in his file. . . .He went off on a wild tangent about how he was going to sue us for antitrust violations . . . that we had been in a conspiracy with Union Carbide; that he was going to sue us and Union Carbide; that he had enough in the file that . . . their rearend was hanging 11 miles out in right field.”

Henry said he listened to the recording and heard “nothing but . . . him giving . . . Carl Nutter a chewing out, and Carl was only getting a word in every so often. . . .I heard the tape recording, and to me it didn’t mean a thing. He went off cussing and talking about how sorry Carl Nutter was . . . and I asked him, ‘If you have never met the man . . . how do you know he is so sorry?’ . . . and [Jimmy said] ‘He is the only person I know that is sorrier than Raymond.’ … I was just going to pretty much agree with whatever he said and get the meeting over with … the man was acting irrational.” Henry asked Jimmy what kind of deal he had in mind, and Jimmy replied that he would send his son Mark around the next morning with some facts and figures.

After Mark delivered the material, Jimmy waited for several days. Just before Christmas he telephoned for an answer. The Fredemans were away for the holidays, but Doug Williams gave him a message. The Fredemans had no intention of making a deal, and as Jimmy Lee remembered, Williams advised him to get his ass back to Mississippi where he belonged.

Williams denies saying anything like that, but Jimmy told me he remembered the contempt dripping from the Gray Fox’s voice. What gall! The proudest single thing in Jimmy’s life was the fact he had grown up in Sabine Pass, Texas: if he belonged anywhere, it was there. What arrogance! He knew then that he had to bring down the Fredemans and all their hirelings, even if that meant bringing the Lees down with them.

In January 1983 Jimmy contacted Houston attorney James A. Drexler and filed a federal antitrust suit, naming Cap Fredeman, his two sons, and his son-in-law, James Crawford—and the entire Fredeman empire—as defendants. The suit charged that the defendants monopolized and conspired to monopolize midstream fuel sales by stealing, bribing, and defrauding. Later, Doug Williams and other Fredeman employees and associates were named as co-conspirators.

Jimmy Lee didn’t expect people to rally behind his crusade, and he was right. The Fredeman legend was too imposing. There were a number of reasons that people in Port Arthur might maintain a healthy respect for the Fredemans or even admire them, but according to witnesses cited in the lawsuit’s final pretrial contentions, what the Fredemans inspired among many on the waterfront was a visceral fear. It wasn’t immediately clear what dark powers the Fredemans were supposed to possess, or where they reached, or to what end—but it was clear that people didn’t want to find out.

In the wake of what should have been the most-talked-about lawsuit in local history, there was a deathly silence on the waterfront. Boatmen who had bitched and moaned about the Fredemans for years locked their doors and pulled their blinds when Jimmy Lee’s pickup stopped in front of their place. Maybe it was just a coincidence, but four days after Jimmy filed suit, a gunman driving along the highway to Sabine Pass fired four shots at the yard of Union City, then sped away in the dark. Nobody was hurt—the shots hit the dispatch shack and one of the boats—but after that Jimmy Lee started carrying a gun, and so did a lot of other people. If the incident was intended as a message, nearly everyone on the waterfront got it. A number of current and former Fredeman employees—and some Lee employees, for that matter—pleaded Fifth Amendment protection rather than give depositions in the suit. Final pretrial contentions filed by Jimmy Lee’s lawyers alleged a pattern of threats and intimidation: “Henry [Fredeman] told him that if he told the truth, [it was] Slay and the other guys on the boats who would go to jail, and the Fredemans would still be sitting pretty. The Fredemans could buy some of the best lawyers in the country. . . . [As Slay] left Henry’s office, Henry followed him to his pickup truck. Henry was getting more impatient. ‘Bill, all the records have been destroyed.’ Slay was scared. He had remembered hearing Henry talk about using muscle on the men. . . .

“Leslie Maxwell was another employee who felt threatened. When Bill Slay called for Leslie, his wife answered and was in a state of alarm about what the Fredemans might do. Her husband said that he heard that Henry would use muscle on anyone who talked.”

The pretrial contentions alleged that another former Fredeman employee, Don Raney, quit rather than steal: “Like Slay, [Raney] got calls at night. They were to the point: ‘If you talk, you’ll be a dead man.’ His tires were slashed. His W-2 sent from Channel listed: status ‘deceased.’”

The local media treated the suit as a nonevent, lending a hollow ring to the Fredemans’ accusations that the Lees were generating and exploiting negative publicity. For more than a year after the suit was filed, there wasn’t any publicity, negative or otherwise. Then on February 26, 1984, the Port Arthur News got around to the headline Threats, Bribes Claimed on Waterfront. At about the same time, Port Arthur’s NBC affiliate, KJAC-TV (Channel 4), also reported the allegations. The story included an on-camera interview with John Palmer, who said that the Fredemans “make Billy Sol Estes look like Walt Disney.” However, when NBC network news did a three-minute segment on the legal problems of the Fredemans last October, its Port Arthur affiliate experienced an untimely seven-minute power failure. Channel 4 had the story on tape, of course, but never bothered to show it or even inform viewers that the Fredemans’ troubles had aired nationally.

Just about the only things that kept Jimmy Lee in the fight were his junkyard-dog tenacity and a couple of breaks on the financial front. Displaying the kind of judgment that helps explain the world debt crisis, CIT reconsidered its position and decided to reopen Union City’s account with a $750,000 line of credit. Then Allied Merchants loaned the firm $150,000. By the end of January Union City was back in business, however tenuously.

There were constant attempts to harass the Lees. Someone would telephone a fuel order in the middle of the night, and a Union City fueler would be dispatched miles down the canal only to discover that no one was there. What was more, Union City was finding it difficult to purchase fuel around Port Arthur; it had to go to Texas City or Lake Charles to refill barges, which increased costs even more. In the spring of 1984 Union Carbide canceled its contract with Union City on the grounds that Union City’s expenses per ton-mile were going up. Jimmy had no option except to claim bankruptcy.

But some things did go right for Jimmy Lee. Back in November 1983 the Bean family joined the Lees’ lawsuit. Though not as wealthy as the Fredemans, the Beans had substantial economic and social standing. Patriarch George Bean had been one of the first midstream operators on the Gulf Coast, and the family had been in the auto supply and industrial supply business for years. Since 1976 George Bean’s nephew Harold “Butch” Bean had run the family’s Marine Fueling Service.

The plaintiffs’ final pretrial contentions alleged: “Marine Fueling had a problem with the Fredemans in the midstream business. The Fredemans could buy diesel fuel for a quarter a gallon, sell it at an announced price of a quarter a gallon, and deliver ten percent fewer gallons than they billed their customer for. At that rate, they would make a ten percent profit, which amounts to two and a half cents a gallon. That can add up when you make deliveries of tens of millions of gallons . . . over the course of a year.”

For years the Beans said and did nothing. George had known the Fredemans most of his life, and no matter what suspicions he might harbor, he wasn’t the kind to get involved. Suddenly, however, the Fredemans began to pay considerable attention to the Beans. Sydalise telephoned George and said she hoped he wouldn’t get involved with that awful man, Jimmy Lee. Henry Fredeman called Butch Bean to feel him out about the lawsuit.

“The thing that finally convinced me that we ought to take part in the suit,” Butch Bean said, “was all the attention we were getting from the Fredemans. They’d never paid attention to us before. I came to believe that if they had done all those things to Jimmy Lee, they had done them to Marine Fueling too.”

In joining the lawsuit, the Beans brought with them prestige and new sources of funds, but more than that, they brought a sense of momentum, a feeling that the Fredemans weren’t going to win the battle merely because they were the Fredemans. The Lees had amended their suit to include complaints under the RICO statute. Their sense of momentum was heightened by the arrival of crates of documents subpoenaed from PATCO and its subsidiaries. Although Channel Fueling’s 1980 files had been burned, there were plenty of other records.

Jimmy was particularly interested in the boat logs from the towing company. In recent years a number of towboats and barges owned by PATCO had been under exclusive lease to the Department of Defense, which paid a flat monthly rate plus all fuel costs incurred to transport barges of diesel and jet fuel for the armed services. The logs were filed daily, giving the DOD the position and state of readiness of each vessel. Jimmy wasn’t the only towboat operator on the waterfront who believed that PATCO had been “doubledipping”—using vessels under exclusive lease to the government for other jobs, charging the DOD not only for the vessel but also for the fuel—and hiding the activity with false position reports. He hoped to discover evidence among the thousands of randomly mixed boat logs.

Meanwhile, at the courthouse one of the first official acts of Patton, Boggs, and Blow as the Fredemans’ new counsel was to file a motion to dismiss and for summary judgment. The attorneys argued that the complaints were a sham and a bad-faith pleading. Furthermore, they argued, the Beans and Lees had engaged in “systematic unlawful activities, such as theft and fraud, which constitute unclean hands and bar relief under the RICO statute.” As evidence of those accusations, the defense lawyers offered excerpts from depositions in which members of the Lee family admitted stealing, bribing, and lying.

Indeed, in discussing their criminal activities under oath, the Lees couldn’t have been more forthcoming.

Mark Lee on theft:

“Q: Generally, you know that the captains [of Union City fuelers] follow the routine practice of hitting boats in talking about it all the time, don’t you, generally? You said you were here to tell me the truth. That’s the truth isn’t it?

“A: Yes.

“Q: After you graduated from college [and went to work for Union City Fueling]…you know they were stealing…And it didn’t bother you a bit. It didn’t bother your conscience at all; isn’t that true?

“A: That’s right.”

Mark Lee on bribery:

“Q: Do you know why a [towing company] quit Union City?

“A: Because we quit bribing them.

“Q: Because you quit bribing them?

“A: Yeah.

“Q: You were bribing their fleet, sir?

“A: With cash.”

Jimmy and Raymond both owned up to hitting boats and bribing tugboat captains as far back as the early days of Lee Marine in the sixties. Jimmy estimated that Lee Marine stole 25,000 gallons a month from its customers. Jimmy also admitted, as he had already done to CIT Corporation auditors, to submitting phony invoices, and he acknowledged that Union City had bribed a CIT emeployee with a Rolex watch and a set of golf clubs.

“Indeed,” the document filed on behalf of the Fredemans stated, “[the Lees’] admitted conduct is identical to that which they merely allege against Channel Fueling.”

The document also quoted from the depositions of four former employees of the Beans’ Marine Fueling who testified that “Marine Fueling consistently ‘hit’ its customers.” For the first time the Beans had been accused of something dishonest. The accusers were two sets of brothers: Ed and Dominic DeTommaso and Tommy Joe and Billy Allen Rampy. All four were employed as dock supervisors at Channel and testified that to their knowledge Channel had never stolen a penny. Final pretrial contentions filed by the other side pointed out that not a single witness had come forward to corroborate the men nor did an examination of Marine Fueling’s own books show evidence of theft. Moreover, another former Channel dock worker, Silas Bell, in an earlier deposition testified that Bill Rampy had ordered him to steal and in fact had personally trained him to rig meters for Channel.

The Fredemans’ motion to dismiss was filed on November 23, 1983. A few weeks later the Lees and Beans filed their response. When U.S. district judge Robert Parker had finished reading the two documents, he not only denied the Fredemans’ motion but also turned the whole mess over to the FBI and a federal grand jury. Jimmy Lee had apparently turned up the first piece of hard evidence against the Fredemans—six boat logs for the motor vessel W. F. Fredeman, Jr. assured the DOD that the vessel was standing by at the Fredeman shipyard, awaiting orders; yet corresponding logs labeled “For Office Use Only” showed that the W. F. Fredeman, Jr. was somewhere else, working for PATCO.

One log, for example, showed that in March 1980, while the W. F. Fredeman, Jr. was supposed to be standing by for the government, it delivered a barge to Norco, Louisiana, waited while the barge was filled with fuel, then towed it to Vicksburg, Mississippi. In response to the defendants’ motion for dismissal, Lee’s lawyers asserted: “The government was apparently billed by Port Arthur towing for thirty-one days charter of the [tugboat] at $5,000 per day . . . and was additionally billed by Port Arthur Towing for thirty-one days charter of the Barge 506 at $450 per day.” And that didn’t include at least 27,560 gallons of fuel, which was also charged to the government. The fuel was purchased from Channel, which, the pretrial contentions alleged, charged the government approximately five cents a gallon more than it charged other customers —in 1982, for example, Channel sold more than a million gallons to the government. “No doubt this vastly understates the amount of the overcharge,” the document said, “since Channel could loot boats leased from her sister company at will.”

When questioned about the charges of double-dipping during the course of his deposition, Bill Fredeman deferred to his underlings at PATCO: “I have been told by my salespeople that the government has allowed them to do other work with the vessel that is under contract to the government.” As for the amount Channel charged government-leased PATCO boats for fuel, Bill said that though the invoices came across his desk, he didn’t look at the price. Asked if he felt any obligation on behalf of the government to obtain a fair and reasonable price for fuel, Bill replied, “I never really thought about it.”

The subpoenaed boat logs turned out to be a revelation even more spectacular than John Palmer’s testimony. Lawyers for the plaintiffs said that those six logs were a mere sampling of the Fredemans’ corruption and mendacity, that “after the filing of this lawsuit, the Fredeman organization destroyed many of the ‘for office only’ boat logs, so only a few survived.” The Fredemans maintained that the for-office- use-only logs were merely hypothetical, to which the opposition pointed out, “They are hoisted on their petard because various checkpoints along the Intracoastal Waterway run by the Corps of Engineers confirm the accuracy of the ‘for office use only’ logs. Moreover, how can they explain billing the government for fuel purchases made in the course of ‘hypothetical’ jobs?”

The boat log allegations stirred up considerable consternation at Patton, Boggs, and Blow. In the fall of 1984 Larry Meyer, one of the firm’s antitrust lawyers, wrote several memos suggesting that the firm quit the Fredeman account, even though the Fredemans were among the firm’s largest clients. In one memo Meyer suggested that Bill Fredeman had admitted to him that the boat logs had been destroyed. The law firm didn’t quit the account, but in May 1985 Meyer did. Even though he had been with Patton, Boggs, and Blow for twelve years and was a senior partner earning more than $500,000 a year, he resigned. So did his wife, Linda Elizabeth Buck, who was also a partner in the firm. At roughly that same time, three other lawyers-at least two of whom had worked on the Fredeman account—also quit. When I asked Meyer if his resignation was related to the allegations that documents had been destroyed, he paused for a long time, then said, “I can’t comment on that.” His letter of resignation was vague, but his wife’s letter stated that she quit for the same “ethical considerations that mandate [my husband’s] withdrawal.”

Since their resignations, Meyer and Buck have received numerous anonymous death threats. Meyer was scheduled to testify before the grand jury in Beaumont last November, but federal prosecutors changed their minds. It seemed likely that anything Meyer had to say would be part of a related but separate investigation.

It was a bodacious brawl, even by Port Arthur standards. Allegations and counterallegations touched the refineries, the banks, the marine industries, high society, low society — nearly every family in town had at least an indirect involvement or knew someone who did. There was talk that assistant U.S. attorney Mike Bradford, who was in charge of the grand jury, had petitioned the Justice Department to file charges under the RICO statute, which carried a penalty of twenty years on conviction.

With that in mind, Bill Slay, whose daddy was so frightened that he wouldn’t even discuss his own years at PATCO, contacted the feds and admitted that he had stonewalled when they questioned him in 1980. But now he was ready to talk. In a twelve-page statement written in the fall of 1983, Slay named the Fredemans and the Lees as longtime criminals. Slay came armed with documents, copies of records he had kept as dock manager of Channel’s Port Arthur facility.

These documents indicated that February 1979 was an excellent month for stealing. Slay’s record showed an overage of 273,640 gallons, 15 per cent of the total sales that month.

Henry Fredeman denied having any personal knowledge or recollection of Slay’s furnishing him with those reports. In any case, he said, Slay was not a trustworthy witness; Henry had heard from a Channel dockworker in Houston that Jimmy Lee had bribed Slay to testify against the Fredemans.

Slay denied that that had ever happened, and so did Jimmy Lee. Except for one Channel dockworker in Houston, who also said he had heard it from Slay, no one else came forward to support the accusation.

About that same time the Fredemans countersued for $100 million, alleging that the Lees, the Beans, and others had conspired to bring down the Fredeman empire. “Others” included Bill Slay and twenty “John Does,” presumably to be named later. It also included CIT, which was later severed from the suit. In the weeks that followed, other corporate entities were sucked into the maelstrom, including Union Carbide, gaugers E. W. Saybolt and Company, and a little-known brokerage outfit called Gulf Coast Petroleum.

If the records that Slay kept were in question, there was no question at all about boxes of the additional discovery materials that arrived; they came directly from Channel Fueling, and they detailed purchases and sales of fuel for 1979, 1981, and 1982. With Channel’s in-house accountant, Jerry Cabbage, looking over his shoulder, the Lees’ attorney William H. White, of the Houston law firm Susman, Godfrey, and McGowan, began to total and chart the figures. White, an expert in white-collar crime and skilled in accounting, had recently joined the plaintiffs’ team and had already spent hundreds of hours poring over the records in search of the proverbial smoking gun. When he thought he had found it, White reviewed each step with Cabbage.

This was White’s procedure: He added the fuel from 1981’s beginning inventory to fuel purchased that year, and subtracted fuel used in Channel’s own boats, as well as the fuel in the ending inventory of 1981. That gave the total amount of fuel Channel had available to deliver to customers. White then used the same procedure for the 1982 records. It was a simple matter, then, to compare amounts available with amounts sold. Although Cabbage argued with some of the lawyer’s accounting methods, court documents in a related case indicated that he didn’t question the bottom line—it showed that in 1981 and 1982 Channel Fueling had sold 12.8 million gallons more than it had available to sell.

How could that be? Henry Fredeman and Jerry Cabbage offered three possible explanations. First, it was possible that the refineries failed to charge Channel for the fuel, and therefore it did not show up on Channel’s record of purchase. Neither could offer evidence that this had actually occurred. Second, the fuel may have expanded inside the barges, an explanation that appears to defy the laws of physics; expansions from temperature variations are measured in tenths of a per cent. And third, there could have been some problem with Channel’s meters. When questioned about the discrepancy, Henry Fredeman said he was not aware of a multi-million-gallon overage, nor to the best of his knowledge had he discussed it with Cabbage.

The next shipment of subpoenaed documents produced a smoking cannon. Jimmy found scraps of paper with handwritten notations indicating that Channel Fueling was paying kickbacks for every gallon of fuel delivered to Union Carbide and several other corporations. The kickbacks were actually paid to a dummy corporation in Harvey, Louisiana, called Gulf Coast Petroleum, which in turn shared the dirty money with executives at Carbide, Ashland Oil, and other companies. A telephone call to the Secretary of State of Louisiana revealed that one of the incorporators of Gulf Coast Petroleum was none other than Carl D. Nutter, who as Carbide’s manager of inland barge operations had tried to pin the theft of 46,000 gallons of fuel on the Lees.