This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Radical Shiite Muslims are blowing up Beirut on Good Morning America, but Sandi Barton isn’t watching. The explosions and cracks of rifle fire are muffled puffs of sound coming from the TV in the living room; Sandi is in her bedroom, where she sits brushing blush on her cheeks to the bright light of a Clairol True-to-Light mirror. The pupils of her hazel-colored eyes are tiny black dots—she makes up her face to what she calls scare daylight. Setting a tray of Estée Lauder makeup down amid an array of eyeliner wands, blushes, compacts, lipsticks, and canceled checks, she squints at her rolled-up dark blond hair. She decided not to wash it this morning, and that may have been a mistake. As she starts to take out the curlers, bombs shake the hills of Lebanon around the world via satellite. From the corner of Sandi’s bedroom, it sounds like somebody is saying, “Shhhh.”

Sandi has worked as a secretary at the downtown Dallas Sanger Harris store since she was 17 years old, and she’s thinking about staying there until she puts in her twenty and can retire. She is 27, she lives a block away from Greenville Avenue in a singles apartment complex, she drives a bright yellow Corvette, she spends most of her money on clothes, and she once tried out for the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. If there is such a thing as a typical Dallas secretary, Sandi is it.

Her roommate, Carol, had gotten up, showered, dressed, and left for her job at an insurance company downtown by the time Sandi woke up to the sound of Culture Club’s “I’ll Tumble 4 Ya” on KEGL. Sandi burrowed under a sheet, a comforter, and a thick blanket embroidered with the face of a tiger, and then she reached out into the cold apartment air and fumbled with the radio on the nightstand, looking for KVIL so she could hear the winning number for that morning’s Fantasy Line contest. After listening to a Barry Manilow song and some commercials, she realized that somebody had won a car, but she wasn’t it.

At 8:05 a.m. her phone rings, and Sandi, who has brushed out her hair and decided it looks okay, picks up the fake-antique brass-plated receiver by her bed. “Hiiii, Richard,” she says to the man she carpools with. “Okay. So it’s running for a change, huh? Right. See you in a minute!” She hangs up and takes a last look at her room.

It is crammed with stuffed animals—there’s a gaudy blue donkey that her high school boyfriend, Johnny, won for her at the state fair, and next to it on the dresser there’s a unicorn and a dolphin, and around the room are scattered a lion, a raccoon, a moose, a dog, and various other fuzzy animals. They all have sentimental value, totems from past and present beaux.

Five pairs of shoes are scattered on the carpet outside her closet, and fifty pairs of shoes and boots, all in their original boxes, are stacked inside. A dozen pairs of size 7 Nikes, Pumas, and Adidases are in a tumbled pile of powder-blue, pink, and white stripes on the closet floor. The bedroom is packed with Sears’ Open Hearth furniture, the heavy kind with rollers on the bottom—there’s a bureau, a desk, two chests of drawers. Scattered on the bureau are pictures of Sandi’s nineteen-year-old brother, Perry, who still lives with her parents in Wilmer, a Christmas card photo of Yolanda, a girl she used to work with, two pictures of her boyfriend, Kenny, sitting in his 280Z and scuba diving on their trip to Hawaii, three small framed portraits of Sandi, twenty bottles of nail polish, and little stuffed bunnies, gorillas, and panda bears.

Sandi sniffs. She goes to the bathroom and is swallowing a Dimetapp for her allergies when she hears the familiar rumble of Richard Meredith’s Z28 Camaro outside her patio door.

She steps out into the cold, burning light of morning cutting quite a figure—she’s wearing a wine-colored silk coat-dress and gray suede pumps, and five bulky gold rings gleam on her fingers. Before she slides into Richard’s car, she glances at her Corvette to see if it’s been bashed in or anything during the night. She hates to drive it downtown and leave it in some lot, so she carpools with Richard, an accounting manager at Sanger’s, in the morning and takes the bus home at five. Her Corvette, which has made it through the night unmolested, has a license plate that reads, “4 Sandi.” It’s one of those things that can be misleading about Sandi: she’s an executive secretary downtown, she lives near Confetti and the Village Apartments, and she drives the kind of car one associates with sleek, mysterious women who wear no panties under their black dresses and who order drinks that bartenders have never heard of long after midnight in the back rooms of bars. But Sandi hasn’t really changed much from the girl who graduated from Wilmer-Hutchins High School in southeastern Dallas County a decade ago. She seems younger than 27, she’s always kidding around, and that voice—it’s so wildly modulated and full of laughter that if you close your eyes, she sounds like she’s still 16, just back from a date. And if you look closely at the Corvette, you can pick out two little fuzzy animals inside, clutching the rearview mirror with their paws.

Richard is a big man with the build of an interior lineman, and he looks out of place squeezed into the contoured bucket seat of a car essentially designed for teenage hot-rodders. But as he pulls into the heavy traffic on University Boulevard, he’s obviously at home, zooming in and out of lanes, cutting into little crevices in the traffic, to make it downtown in nineteen minutes flat.

Richard pulls the Z28 into a parking lot where he rents a space by the month, and they walk the two blocks to Sanger’s. They can see their breath in the bright morning light. Walking past a sign that reads “Foot Traffic Prohibited,” they take a shortcut through a parking garage, and then the Sanger Harris building looms before them at Pacific and Akard, a tall, block-wide building with a colorful mosaic pattern on its smooth white sides. They walk through the only unlocked doors and whoosh, the escaping blast of warm air tousles Sandi’s hair to smithereens, just as it does every morning.

“See you,” says Sandi, as Richard turns to walk down the escalator to his department on the sublevel. In an elevator hidden by a display of marked-down men’s blazers, Sandi pushes 4. She’s on automatic payroll, so she doesn’t have to punch a clock or anything. But she has to be in by eight-thirty and leave no earlier than five, because she’s surrounded by bosses who get there earlier and are still there when she leaves. On the elevator, capital letters spell out the departments one can find on the fourth floor: Home Furnishings, Interior Decoration, Executive Offices.

Sandi works on the other side of the store from the executive offices. Just past a row of splendidly decorated living rooms and bedrooms, whose painted windows offer views of countrysides and sunny beaches, down a hallway with beige walls and a brown carpet, is her desk, bathed in harsh fluorescent light. The furniture department seems to carry over into Sandi’s office—her area has the look of a room that’s been decorated but never lived in, a room that a thousand people have walked through but where few have ever lingered. Plastic is still wrapped around the shade of a brass lamp, which sits on a glass-and-rattan table. A sticker is pasted to the table’s glass surface; it reads, “Made in Belgium.” Low-slung oak-and-leather chairs sit around her desk, and the ashtrays look as though they’ve never been used. Inside one of them is a book of matches and a couple of staples.

Sandi’s space has few personal touches. There’s a single tiny mirror on the blank wall above her desk, a coffee mug with “Sandi” printed on it, a memo-pad holder bearing the gold initials “SB,” and a little Sears clock radio, which Sandi turns on reflexively and adjusts to a nearly inaudible volume.

Sandi has been working in this office for nearly two years, but it is strangely unfamiliar for her this morning. Two weeks ago her boss, Ted Hochstim, left to go into business for himself. Now she has a new boss, a vice president named Glen Griffith, who brought two associates with him—Mike Blair and Joe Phillips. Doors were knocked through the walls near her desk and two new offices appeared, along with two more phone lines. The stink of fresh paint and the dust kicked up by the drilling and sanding triggered an allergy attack, and Sandi had to take a day off work. But things aren’t all bad—she makes a little more now than the $15,600 she made working for Mr. Hochstim.

Sandi has already washed out a glass decanter and brewed some coffee, so she walks into Mr. Griffith’s office to say good morning. He’s behind his desk looking over some papers. Wearing glasses, a conservative navy-blue suit, and a sensible tie, Mr. Griffith has an air about him that sets him apart from the mid-level executives in the building—the department heads, the sales associates. Those men always seem to be in their shirtsleeves, and they take time to flirt and joke with the secretaries. They smile more, laugh more. They indulge their mood swings. But at the top, the bosses—Mr. Griffith, Mr. Hochstim when he was here, Mr. Miller (the chairman of the board), Mr. Griffin (the president)—exude a self-assured calm that’s almost saintly; they move about in a distracted slow motion, as if they’re lost in a world of bewildering worries and enormously important decisions. They seem graceful when they stroll out of their offices and approach their secretaries with an empty coffee cup or some memo tapes ready to be typed.

That same abstract prestige settles over their secretaries as well, nowhere more so than at the desks of Nancy Larcaide and Billie Bagwell, who sit side by side at massive desks that guard the entrances to the offices of Mr. Miller and Mr. Griffin. Everyone treats Billie and Nancy with respect simply because of whom they work for—people speak more softly to them. Sandi would like to be sitting at one of those desks one of these days. Who knows? Maybe Mr. Griffith will end up there and take her with him.

“I just made a fresh pot of coffee,” she tells Mr. Griffith.

“I’d love some.”

“Okay.” She walks out of his office and encounters Mike Blair, who has already purloined a mugful from the little kitchen-photocopier-filing room. “If you didn’t drink it all,” Sandi teases.

“I drank it all,” Mike says in his mocking bass voice. “You’ll have to make another pot.”

“Oh, brother.”

He goes in to talk to Mr. Griffith, and when Sandi returns, she sets her boss’s coffee on his desk without interrupting their conversation.

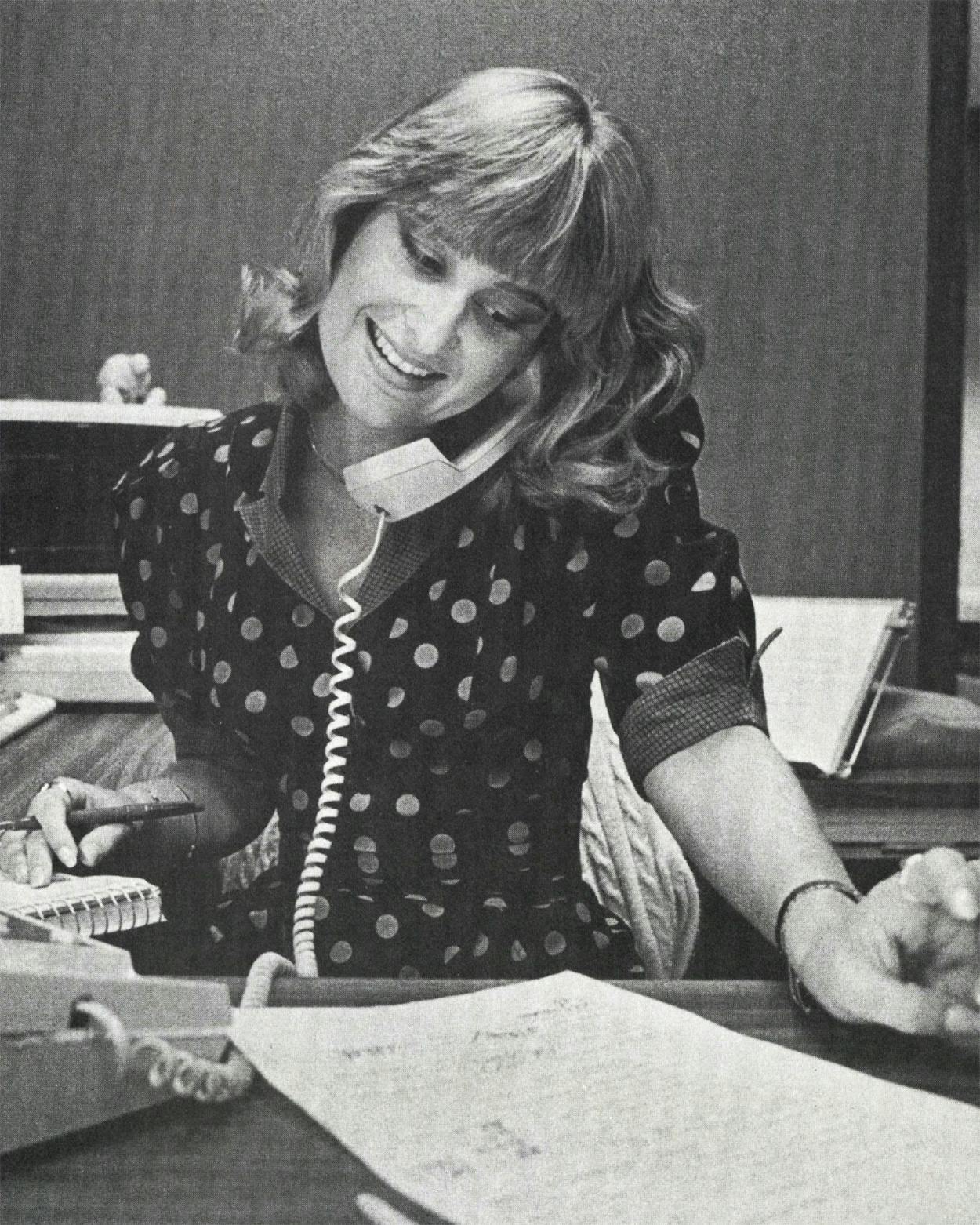

Letters, letters, letters.” Sandi turns her chair around to face an imposing black IBM Selectric, puts in a sheet of paper, sets the noise damper down, slips on the earpieces of a dictating machine, and begins to type the letters that Mr. Griffith dictated yesterday. There’s a jumble of sounds in the room: the chunk-chunk-chunk of Sandi’s ninety-words-per-minute typing, the muffled male mutterings coming from Mr. Griffith’s office, the slick scrinch made by the wheels of Sandi’s chair as they roll across the plastic rug guard whenever she picks up one of the chirrrping phone lines, the faint jingle of the Go-Go’s “Vacation” coming from Sandi’s radio, and the distant noise of the store, which is like the sound a seashell makes when you hold it up to your ear.

Sandi dials 3112 on the interstore line. “Hi, Toni. What’s the payoff song today? You still haven’t heard it? Well, how can we get rich if you don’t listen? Okay. Call me if you hear it, or I’ll call you.” The payoff song is one of the many radio and newspaper contests Sandi keeps track of. The FM station KEGL announces it in the morning, and when the DJ plays it later in the day, the thirty-ninth or so caller wins $1000. Toni is Sandi’s best friend at Sanger’s and has been for a year and a half. They eat lunch together every day, at the submarine shop on Akard, at Hamby’s up Pacific, or at the salad place in the underground. Toni is as sharp as they come—hip and sardonic, with a caustic wit that comes out in every sentence. She works in an office on the dock level and is one of the best sources of information at Sanger’s. They make a funny pair, this knowing, married, smirking Oak Cliff woman and this cute, blond, Upper Greenville woman, but when they’re together their sarcasm and their stories make them a team, like Stiller and Meara.

An imposing, attractive woman strides up to Sandi’s desk and stops a little too close.

“Are you Sandra?”

“Uh-huh,” Sandi says, a little suspiciously. This could only mean trouble, or more work. While they talk, Sandi’s voice is lower, tougher, than usual.

“I’m Joan Jackson, in Statistical. Are you doing the passwords and stuff?”

“Yes.”

“We tried sending up two sets of requests. Are you behind on them or . . .”

“What were the names?” Sandi asks.

Part of Sandi’s new job is assigning, updating, and encoding passwords to the stores’ advanced computer systems. Mr. Griffith is in charge of everything to do with computers at all the Sanger’s stores and at other stores in the Federated chain in Miami, where he spends every other week. And everything at Sanger’s has something to do with computers. Fashion, payroll, personnel, cash registers, purchasing, buying—they’re all hooked into the computer. Each employee has a password that lets him into the system and a limit on how far he can get into it, how much he can change. Passwords take up a lot of Sandi’s time and cause her a lot of aggravation. Sandi looks through her files for the computer password lists and sees that they are updated.

“So we get access?” Joan asks.

“Umm-hmm.”

“Thank you very much.”

Since she started working for Mr. Griffith, she has been missing a lot of those payoff songs on KEGL-she’s too busy. When she worked for Mr. Hochstim, she had more control over her time and her work. She had only one boss, one phone to answer. Mr. Hochstim did real estate deals for Federated Department Stores, which owns Bloomingdale’s, I. Magnin, and Foley’s as well as Sanger Harris, so Sandi didn’t actually work for Sanger’s. She had her own little world in this corner of the fourth floor, and Mr. Hochstim trusted her completely. Before he could ask her to do something, she’d already have it finished. That magical prestige Nancy and Billie have in the executive offices surrounded Sandi in some ways too. (“That’s Sandra Barton. She works for Federated up on four. I’m not sure what they do up there.”) She didn’t have to fill out all those darn Sanger Harris forms. And inside her cocoon of an office, while Mr. Hochstim was away on one of his frequent trips, she could catch up on filing or on work for the deal they’d be doing that week and take time to read a paperback mystery or romance.

Now there is almost never time for that. The phone rings constantly; when Mike and Joe are out of the office, she has to take their messages, and people are always calling about their passwords. Her new job seems chaotic and so different from her old one. And she’s still breaking in Mr. Griffith; they’re approaching each other cautiously. Mr. Hochstim was a hard act to follow —he was everything Sandi thinks a good boss should be.

“A good boss really likes you,” Sandi says, “and feels confident that you can do his work and trusts you to do the things you’re supposed to do for him. It takes time to build that kind of working relationship. A good boss understands that you’re a person, not just somebody who’s sitting out there, that you have good days and bad days just like him and everybody else.

“When you’re a secretary, you have to be energetic and so on top of things all the time, and it can be hard. Like, people call you on the phone, and you have to think about the call and write down the message or deal with the problem and then turn back around and focus on what you were typing—what line was I on?—and at that exact moment your boss might want you to come do something in his office, or the coffee will be empty right at that moment and you got to go make it, and then when you’re doing that, another boss calls out, ‘I have a meeting at two o’clock,’ and you have to write it down on your desk right then and in a minute go in and write it on his calendar, and the phone is ringing again. So if your car is broken down or you don’t feel good or something, you can have trouble getting everything straight. You can goof things up.

“Some people feel that being a secretary is a real meaningless, demeaning job, especially in the new women’s-rights wave. Sometimes when I meet people, I tell them I’m a secretary and they just kind of go, ‘Oh, really?’ or something like that. They think maybe you could be a big executive-type person. It doesn’t really bother me. A lot of people, no matter what you do, they’re going to frown on it.”

Sandi is riffling through a sheaf of papers covered with numbers, saying half aloud to herself, “three . . . seventy-five . . . sixty-forty-two,” when her train of thought is interrupted by a deep male voice saying, “Hello there.” It’s Mike Blair, his hands in his pockets and his jacket on his arm, back from a few hours at the warehouse. He walks into his office, and Sandi shouts after him, “I got you that dental appointment.”

“When?”

“Seven a.m. Now, what dentist gets to his office at seven in the morning?”

“He does, once a week, for people like me,” says Mike.

“Oh, where’d Carol Ann go? She’s always disappearing.”

Carol Ann started at Sanger’s the same time as Sandi, and she too was Mr. Griffith’s secretary. She left the company a year ago, but she comes in now and then to work part-time, helping out. Today she is in Mr. Griffith’s office, catching up on paperwork and helping Sandi get acclimated. Carol Ann and Sandi are old friends. They haven’t seen each other in a long time, but they always fall back into their friendship easily. Carol Ann is funny too and as nice as she can be.

Sandi punches 3112 again. “Hi, Toni. Did you bring your lunch today? Well, you big dummy! Shop? You can’t shop! You can’t buy anything until the big discount starts on Friday. For what? Oh, yeah, we’re going to the big deal at Tango tonight, aren’t we? Okay. Well, anyway, me and Carol Ann brought our lunch today, so we’re going to go downstairs and eat. So why don’t you stop by, and then you can sit with us a minute and then go shopping or something. Okay. I’ll see you at one then. Bye.”

At 1 p.m. Sandi walks into the filing and photocopier room and opens the GE frost-free refrigerator-freezer, grabs her burrito and Carol Ann’s lunch sack, and heads downstairs.

When Sandi and Toni don’t eat at the sub shop or Hamby’s or the salad place, they spend their sixty minutes in the Pit, an employee lunchroom two floors below Sanger’s street level. A sign on the wall urges Sanger’s employees to fink on shoplifting and till-tapping co-workers. A dozen tables are surrounded by plastic chairs, and most of the people in the place are women. The noise of all their laughter and conversation bounces off the windowless walls in an acoustical nightmare. Every twenty seconds or so one of the four microwaves against the walls screams a shrill beep-beep-beep. Across the room people are pulling the handles on a bank of vending machines; odd-looking cheeseburgers shlunk out into their hands. Sandi has grabbed a table near the center of the Pit and is sitting with Carol Ann, Toni, and Mary Kay, who works in the office on the other side of Mike Blair’s.

“Well,” says Toni, “I’ve decided I’m not going to buy any pants. I wanted to get something to go with this black sweater I got. But when you’re looking for something, nothing looks right.”

“Well, discount starts Friday,” says Mary Kay.

“But I need it for tonight.”

“She needs it for tonight so we can make a big splash at Tango,” explains Sandi. “Sanger’s is doing a Daniel Hechter fashion show. Free champagne and food, that’s why we’re going.”

“You two are going to Tango? Will you wear something punk?”

“I’m the punk section,” Sandi says, indicating herself with the stub of the burrito. “I might wear something punk. Her? Ha, ha, ha!”

“I don’t have a punk bone in me,” admits Toni.

“What is that thing tonight?” asks Mary Kay. “Is it a men’s deal?”

“Why else would we be going?” Sandi says. “We sure wouldn’t be going if it was ladies.”

“We’re not going to pick up the men,” says Toni. “We’re just going to look. It’s like going to a candy store.”

“Just doing a little body shopping,” says Sandi.

“To see what you want to buy later,” adds Mary Kay.

“Put something on layaway!” Carol Ann laughs, and everybody is breaking up now. “On hold. What is it—thirty-day or revolving?”

“What a thrill!” Sandi says, with a devilish laugh. “Why, there’s Richard Cauley!”

Everyone at the table simultaneously takes a sharp breath. Cauley, a sort of troubleshooter for Southwestern Bell, used to work exclusively in this Sanger Harris building, installing, repairing, and working on its phone systems. Handsome, blond, and rugged-looking, he’s very unlike the pale men in three-piece suits who populate the store.

“He lost a lot of weight,” Mary Kay says meaningfully.

“He did,” says Sandi. “He looks real good.”

Carol Ann, as if to explain everything, says, “He got a divorce, you know.”

That sets everyone back for a minute or two. Then Sandi gulps down the rest of her drink and says, “Is it time to go back?”

Everyone at the table looks at the clock. It’s 2:02. “It’s past time.”

Sometimes Sandi talks to herself—figures and memos are bouncing around in her head, and they just sort of slip out. At her desk in the heart of the afternoon, when time seems to move with agonizing slowness and the Sears clock radio takes an eon to change from 3:02 to 3:03, Sandi is scanning a page filled with numbers. “Let’s see—let’s see how much money we have left. Oh, boy, a hundred and fifty-five thousand dollars! So we put it here and . . . there . . . this . . . okay. Now.”

“Sandra? I need you to go do something.” Mr. Griffith’s voice, coming from the recesses of his office, isn’t raised above the murmur of his normal phone conversations, but Sandi picks it up, says okay, and walks in. No matter what she is doing, when Mr. Griffith asks her to take a memo or look something up in a file or cash a check for him downstairs, Sandi drops everything right then and there and takes care of it. It’s one of the rules she has for herself.

“Could you get me the payroll sheets for Joe’s thirty-tens?”

As Sandi looks for them in Joe Phillips’ office, her phone starts chirping. She picks up the line back at her desk. “Sandra,” she answers. “Nobody’s in PDS. They won’t be here till tomorrow. Ummhmm.” The people in Planner Distributor Systems have had all their calls forwarded to Sandi while they are out, and it’s driving her crazy. She finds Joe’s payroll sheets, takes them into Mr. Griffith’s office, and makes notes on the figures he wants her to correct. She feeds the big, eleven-by-fourteen sheets into the IBM, brushes the mistakes with Liquid Paper, leaning forward delicately to blow the globby white lines dry. Then she types in the corrections.

“At Sanger’s if you don’t want to be a secretary anymore, you can go into something else,” Sandi says. “If I didn’t want to be a secretary and wanted to be an accountant in Accounting, I could. But I really like what I do, because if you’re someone’s secretary and you get along with them, they really need you. And you feel that they really need you, so you feel like you’re really wanted. It’s not that you have to do some exceptional wonderful project or think up something brilliant to get ahead in your field, but you have to always do things really well and show your boss you really care about what you do and do everything that he says efficiently. But it’s not like you’re under all this pressure that you have to perform so well to get ahead. You don’t have to cut anybody’s throat or try to backstab anybody to get ahead.

“There’s a lot of department managers at Sanger’s that go into a department that’s really messed up. They’re under a lot of pressure to get things straightened out, and if they don’t, they’re out, you know? It just doesn’t seem like a lot of fun, because I don’t want a job that I have to think about when I go home or when I wake up in the middle of the night.”

Ten minutes. She was downstairs only ten minutes, and now there are men tearing up her office. A workman is standing with his grubby feet on her desk, pulling a big piece of acoustical tile from the ceiling. Then he goes into Joe Phillips’ office, where another workman is standing on that desk, snaking coiled wire up into the ceiling. Meanwhile, of course, the phone is chirping. “Sandra in Mr. Griffith’s office. Who? Are you calling someone in PDS? Well, they’re all out, and they won’t be back till tomorrow. I’m sorry!” Specks of acoustical tile are drifting down from the ceiling like confetti, and Sandi reflexively sniffs.

“Hey, y’all!” she yells at the men in Joe’s office. “You’re making stuff fall on my head!”

Mike Blair walks out and laughs. Sandi is clutching Kleenexes to her face as a makeshift gas mask. When she talks, she sounds like a cartoon character. “Don’t worry about it, Barton,” he tells her. “It’s just snowing. Is the copy machine still broken?”

“It was earlier. Pftui! Come on, now, y’all! There’s little pieces of something coming out of the ceiling.” From the hole over her head a coil of wires appears, like a snake. “I have a big ol’ wire hanging down now!”

A workman comes out and looks up, points. “That one?”

“Yeah, that one up there. I’ll have to take another day off tomorrow if I have an allergy attack.”

The workmen leave twenty minutes later, plugging up the hole. The phones have quieted down. Mike has gone back out to the warehouse and won’t return. Mr. Griffith walks out, one hand in his coat pocket, moving with that familiar distracted air. “I’ll be right back, Sandi,” he says.

“Okay.” Sandi opens her drawer and pulls out a candy bar wrapped in violet foil. School candy, band candy, something like that—it’s the tenth bar she has bought this year from fellow employees selling it for their kids. She breaks off one square of the chocolate and munches it thoughtfully, getting a glass of water since candy always makes her thirsty. 4:38. KVIL will announce the Fantasy Line contest winner in two minutes. The day is almost over. She gets one last thing off Mr. Griffith’s desk, slips some letters into envelopes, seals them, dumps them into the box for outgoing mail, puts the cover on the typewriter, and leaves. When the Fantasy Line winner is announced, her comment is “Jesus Christ!”

It’s 5 p.m. and the store is bustling with customers who’ve stopped by after work. Sandi walks over to the jewelry department to pick up a Seiko ladies’ watch she bought earlier in the week, on sale plus her discount. The salesman asks her to try it on; it’s too loose, so he removes another link.

While she waits, a dapper, mustachioed, cheerful-looking man in a three-piece suit walks up to her and says, “Are they selling you a bill of goods?” It’s Arnold Rubenstein, the store manager. “I’m buying a watch.”

“Good! Good! We can use the business!”

Dashing across Pacific with the light, her high heels clicking on the concrete, Sandi just makes the 5:05 Village Express. She flashes her bus pass at the driver, and since this is one of the first stops, she has no trouble getting a seat by the window, on the right side, where she can see people get on and off.

The bus is shaped like a big butter dish; the windows are smoked, it’s warm inside, and it sways with such a quirky, lumbering gentleness that it’s like being rocked in a cradle. The bus nudges its way through the traffic-clogged streets, stopping at corners to pick up coveys of suit-coated businessmen and well-dressed women. It glides onto Central, toward University and home. Sandi looks out the window, and then she pulls a paperback from her purse: Cinders to Satin, “the wonderful new historical romance by Fern Michaels. Nothing could defeat her spirit . . . no one could resist her charms.” Of all the books you can read on a forty-minute bus ride, books like this one are the easiest. Mysteries with complicated plots? Forget it.

Carol is sitting at the kitchen table eating Church’s chicken out of the box when Sandi gets home. Neither of them is any great shakes as a cook.

“What are you doing tonight?” she asks Sandi.

“I’m going to Tango!”

“Oh, yeah—that fashion show, right?” “Yep. What are you fixing to do?” “Oh, just go run some errands.”

Sandi changes into a snug-fitting, sleeveless pink corduroy jumpsuit and a pair of tan suede boots, rushing to meet Toni by 6:15 so they can get a good seat. Luckily, her Corvette has made it safely through the day. She swings open the huge door, sinks down into the cockpitlike interior, and revs up the engine. When she adjusts the rearview mirror, she’s careful not to knock off the fuzzy cat and the koala bear. Then she rolls the car out under the sky and onto Greenville, south toward Tango.

Sandi is not an aggressive driver like Richard; she drives almost tentatively until she reaches the long, wide, empty bridge on Greenville Avenue, where she punches the accelerator and feels some g’s in the bucket seat, sees the reflected streetlights stream across the Vette’s sloping, feminine hood.

Her car safe in the hands of a valet, Sandi finds Toni waiting near the front of a long line. It’s dark, it’s cold, and the club won’t let anybody in yet. Thirty minutes pass before the doors open, and they’re swept inside by the crowd behind them. They get a table upstairs, and a blond waitress wearing an orange Tango flight suit asks them if they want free champagne. They do.

Sandi returns from a scouting mission, squirming her way back through a mass of people who are envious of her table. “The video room and the dance room are deserted!” she tells Toni. “Hey, I’m going to be in Fashion!Dallas, in the paper. The photographer down there by the door took my picture, had me get in these positions and everything. Now I’m going to have to read the darn Morning News until I see it.”

Toni recognizes a buyer on the floor downstairs. “Is that his wife? She looks awful!”

“But he didn’t always look good, either. I remember when he was assistant to the assistant to the assistant. He wore blue jeans all the time. He was Mr. Scrubby Rub. Now he’s a big buyer. And it does make a difference.”

The champagne comes, and they try to decipher its label; it’s French.

“You know,” Sandi says, “we’re paying for all this.” She gestures toward the restless crowd, the popping champagne bottles. “Instead of getting a raise, we’re paying for this. Let’s order ten bottles.”

“There’s that little dip from display,” Toni says. “She causes me trouble every day.” Then Toni leans over the rail and squints. “Look at that girl down there, in the third row.”

“With that streak in her hair, right at the part?”

Toni and Sandi exchange looks.

“Do you think she did that on purpose?” “I guess so. There are lots of bizarre-looking people here. You see those two guys?”

“Oh, God.”

They spot another, incredibly straight-looking couple. “They don’t drink, they don’t smoke, they don’t eat meat, they don’t, they don’t, they don’t,” says Sandi. “And they don’t live together.”

Toni feigns surprise. “They don’t?”

The fashion show is . . . strange. A president of Daniel Hechter is introduced along with the fashion director at GQ, and then these barefoot, golden-robed “Africans” run out, beating conga drums and dancing down the runway, the gold necklaces on the women flailing and jangling in the hot white lights. This goes on a long time, until finally some models come out in the cool summertime casualwear. Then more models. And then the Africans return, pounding their drums and waving palm fronds and making funny sounds from the backs of their throats, twisting and hopping around the stage.

When the models strut back out, Toni and Sandi agree on their favorite, a bushy-headed guy with a hairy chest and a bored, slightly menacing expression. “He’s just my type,” says Toni.

“Is that guy your type?”

“No, but I’m not choosy. You know I married Rich for his money.”

“Yeah, I know. Look. We’re back in the jungle.”

By the time Sandi gets home, it’s 9:30. She’s slightly buzzed from half a bottle of champagne, a gratis hot dog heaped with relish, and about six minutes of dancing to “China Girl,” by David Bowie. She puts her purse and keys on the kitchen counter and walks into the living room, where Carol is curled up on the couch, surrounded by mounds of homework on computer printouts, watching MTV. “How was Tango?” Carol asks.

“Oh, it was just okay.”

The living room, like the rest of the apartment, has that curious look of a place where two disparate and unsettled lives are temporarily thrown together. There’s a wicker chair next to a floral-printed sofa, a framed photograph of the Dallas skyline at night opposite a mirror with green leaves and a moon painted on it. Behind the sofa is a box fan, a portable black and white TV with aluminum foil wrapped around the antenna, and two mirrors leaning against the wall. On the coffee table and by the stereo are copies of Vogue, Mademoiselle, a Dallas Museum of Art bulletin (Carol’s), Us magazine, and Car Craft—“How to Build a 330 H.P. Street V-6” (Sandi’s). The jazz and fusion albums near the stereo are Carol’s; the Journey eight-track tapes are Sandi’s. The roommates have different tastes in just about everything.

Sandi is getting ready for bed when Kenny calls. He had planned to go to Tango too, but then his uncle died from a heart attack. The uncle was just 31 years old. His wife came home from work, and he was lying on the floor, dead. Just like that. The funeral was today, and now Kenny is all upset. He’s 26, and he’s worried that he’s going to have a heart attack.

Kenny isn’t like the men Sandi works for at the store; he’s more like Richard Cauley. He works for a company that puts glass on the sides of high-rise buildings under construction. All day long he drives around in his Blazer, checking jobs. He’s an outdoorsman, a union man. Sandi has been dating him for four years, which may seem like a long time to date somebody. But Sandi sticks with things, just like she’s stuck with her job at Sanger’s.

When she was fourteen years old, Sandi started dating a boy in Wilmer named Johnny. They went out for four years. That stuffed blue donkey on Sandi’s bureau—Johnny’s the one who won that for her on the state fair midway, shooting BB’s through a little red star. When he got out of high school, Johnny became a machinist at a company that made pet supplies, and he wanted Sandi to marry him. But she didn’t want to do that, not at eighteen years of age. She wanted to get out and do things.

Then Sandi started dating Bobby Lee, who’d also gone to Wilmer-Hutchins High School. Bobby Lee’s family was rich—his father owned a construction company—and when he was eighteen, Bobby Lee’s family moved to North Dallas, just kissed the small-town life good-bye. When Sandi broke up with Johnny and started going up to North Dallas to be with Bobby Lee, some of her friends dropped her. They couldn’t believe she’d do a thing like that. She and Bobby Lee were together for nearly four years. He was into drag racing, so for one year she spent all her spare time watching him build his race car in his parents’ garage. Then, almost every weekend for the next three years, she went on the road with him in a four-door double-cab truck, pulling his car in a forty-foot enclosed trailer, chasing down races in Louisiana, California, Florida, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. They practically lived together for the last two years, which Sandi’s parents didn’t like much, not that they tried to put a stop to it. By then Bobby Lee’s dad had helped him buy an equipment rental company, and it seemed inevitable that the next thing to do was get married. But Bobby Lee was scared of marriage. Sandi wasn’t sure why. She wondered if his father was pressuring him to stay single, or if there was some other reason. So things got bumpy, and then Bobby Lee started dating other girls, and that was it.

Six months later, in 1980, Sandi met Kenny. Since then things have gone pretty well. Like most people, they have their rocky moments. They don’t talk about marriage—Sandi doesn’t know whether it would work or not—but what they have is okay for now. If Kenny wants to go out with the guys on a drinking spree, Sandi couldn’t care less. And if Sandi wants to play bingo with her dad or go out with Toni, that’s okay too.

“I really don’t like your banker-type, business-type person, you know, in a suit all the time,” says Sandi. “I like people that have down-to-earth ideas. I’m not a real high-society type. I really don’t care about high society or what the newest art object is or jazz music that much. I’m more into fun, you know, like drag racing, concerts. I mean, I could be sophisticated sometimes. I can go out to a nice restaurant and get all dressed up and be wonderful. I’ve been to society events like charity dances and balls, all that junk, but it’s not my favorite thing to do.”

She is talking about the down-to-earth men in her life when she is asked what happened to her high school boyfriend.

“You know, it’s funny,” she says. “Johnny did get married, to Bobby Lee’s old girlfriend. She’s one of the ones who wouldn’t talk to me after I broke up with Johnny. Well, now they’re married, they have one child and another on the way, and they live in a Fox and Jacobs home in DeSoto. And meanwhile I drive a Corvette and live a block off Greenville Avenue. So which do you think is more interesting?”

Still feeling a slight buzz from the champagne, Sandi sniffs at her bathroom mirror. Those dumb workmen. She’d take an antihistamine if she hadn’t had anything to drink, but now it would give her a stomachache. She brushes her teeth, washes her face with a palmful of cold, creamy Phisoderm, changes into a nightshirt, sets her alarm for seven, and slides into bed. Her eyes adjust to the darkness, and then she hears something—a dull thump, thump, then the sound of a far-off electric guitar and a man singing. The SMU guys upstairs are playing their stereo again. Don’t they ever study? It’s not too loud, it’s just loud enough to make Sandi wonder what the song is. She has heard it before. She’s still lying there in the darkness, trying to remember, when she drifts off to sleep.