This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The boat—the Reverie—is almost new, and except for the few places where the rusted tickler chains have stained the deck, it is absolutely pristine in comparison with some of the older boats. These others seem to slouch, portholed and knotholed, against their moorings, their winches impacted with rust and their nets hanging down like moss, studded with the long-dried-out remains of incidental crabs and small fish.

Though the condition of the boats varies, their design is remarkably consistent, like a whole block of identical model homes. All of them have the same long concave deck, upon the bow end of which a rectangular cabin sits, forever riding the upward slope of a frozen sea-swell. Behind the cabin, a mast rises at least twenty feet into the air, sprouting three long branches from its base. Except for the Reverie, the boats all seem to be christened with hyphenated double names, the names of racehorses and lost women.

When I step on board the Reverie for the first time it seems huge; its 70-foot length and expansive open deck give it the appearance of one of those boats that are chartered for moonlight dancing. This impression of space is to be drastically contradicted during the next two-and-a-half days, but for the moment, wearing a baseball cap, carrying a suitcase packed with an authentic hooded parka, a bag of Oreos, and a copy of The Magic Mountain, I am convinced that I am prepared for anything. In the wheelhouse, Ronald Boudreaux, the owner of the Reverie and of four other boats whose names also begin with R, looks out upon a sandstorm that is raging across the featureless spoil banks of the Port Isabel shrimp docks.

“Well, it’s March and things are crappy all over,” he reflects, leaning his elbow against a nubbin of the helm. Boudreaux is one of those people who wear their fatalism well. The shrimp market is in a nosedive, and with the recitation of each painful detail his face seems to brighten with irony.

“Over the past year fuel has gone up so’s there’s no way you can make money in February or March. If you’re lucky the boat might break even.”

But then he has four boats, each of which burns sixteen to eighteen gallons of diesel fuel an hour, a commodity that has nearly tripled in price in the last year. At that rate he can expect to spend $20,000 a year on each of his boats for fuel alone. Other costs—netting, steel cable, nylon rigging—are up an average of 100 per cent as well.

Then there’s the shrimp slump itself. There are only two major shrimp consuming nations in the world, Japan and the United States. When Japan, which had been stockpiling shrimp for several years, suddenly announced that it was no longer in the market, the U.S. found itself in the unique position of being glutted by no fewer than 85 shrimp-producing countries. The price dropped. The energy crisis kept people away from restaurants, where most shrimp are eaten. The price dropped still further.

“Almost everyone lost money last year,” Boudreaux says, looking out of a porthole and seeming to gauge his economic fate against the ferocity of the sandstorm. “This year looks bad too.”

The wheelhouse in which this doleful discussion is taking place is paneled in wood, laden with expensive electronic equipment, and perched a few steps higher than the rest of the cabin, which it adjoins. The cabin itself looks more or less like the inside of a mobile home, with a kitchen situated at the far end of a hallway which is flanked by bedrooms on one side and by a bathroom and a dining table on the other. A year ago, when it was built, the Reverie cost $116,000. Boudreaux estimates that it would cost $160,000 today.

“If those little crustaceans are a worthy prey, it is because it’s just so damn much trouble to dredge them up out of the ocean and into the shrimp cocktails of the world.”

Soon we are joined by the Reverie‘s captain, whose name is Jose Aleman. “Aleman” is in fact tattooed on his forearm, underneath a representation of a skull wearing a top hat, which contrasts wildly with the captain’s own benign and drowsy face. He has a high, almost whiny voice that is nonetheless curiously soothing, and the L-O-V-E that is tattooed across the knuckles of his left hand seems to be placed there not out of irony or in provocation but as a simple statement. He is 43, and an ex-Marine, but neither fact seems to fit him.

In a few minutes Boudreaux is standing on the dock, waving goodbye. “This is a good crew you’re going out with. I’d come with you but I get seasick.” The boat makes a tight U-turn away from the dock and heads out through a maze of canals into the relatively open waters of the ship channel. Up in the wheelhouse Jose demonstrates the depth scanner and the fathom meter and the radar viewer, letting each point sink in as he negotiates what seem to me some cumbersome maneuvers.

The Reverie, like most shrimp boats, carries a three-man crew. Besides the captain there is the rig man, a kind of first-mate, and the header, a kind of flunky.

David (Da-veed) Campos is the Reverie‘s rig man. When I first encounter him he is in the galley washing the breakfast dishes and wearing a bandana over his head, pirate-fashion. He is as much the prototype of the swarthy shrimper as Jose is not. His face is tight and somber, and bears a certain resemblance to dust jacket photos of Philip Roth; and he has a stocky, athletic body that causes his T-shirt to crease at the pectorals.

Since he doesn’t know much English or, more to the point, since I don’t know much Spanish, our conversations are rather abbreviated and eccentric.

“Get seasick?” he asks.

I shake my head and feel for the Dramamine in my pocket.

“Hah!” he replies.

The third member of the crew, the header, is a seventeen-year-old illegal alien from Matamoros whom we’ll rename Carlos. Headers are called headers because their chief function is the decapitation of shrimp, one of those nagging little tasks that nevertheless leave room for virtuosity. It is (for this time of year when there are few shrimp to be caught) such a low-paying position that illegal aliens are just about the only people desperate enough to sign on. A header makes $7 for every hundred pounds of shrimp taken, and though at the height of the season this can work out to something lucrative, in the early months the pay can be outrageously low.

So few shrimp are taken in February and March that the presence of a header is not even necessary except for insurance purposes. “All you need is a warm body out there,” Boudreaux told me earlier. “During the season, though, you really need that third man.”

Carlos is not yet a proficient header, but he’s only been in the shrimp business for two weeks, not yet long enough to wear out the double-knit bargain basement pants which he always wears, though by now there are a few shrimp feelers caught in the fabric. He has a bright, pleasant face, framed by sideburns that thin out at his jawline. He speaks no English, in fact rarely speaks at all, preferring to stand off to the side and smile indulgently at any proceedings that might be taking place.

Once out of the canals the Reverie joins with four or five other boats that are heading for the bar, the extreme southern tip of Padre Island where a single jetty supervises the commingling of the Gulf of Mexico and the Laguna Madre. The other boats, with their nets splayed out from the two outriggers that branch off the mast, look like huge, extravagant seabirds skimming the surface of the water with their wings. Through the sandstorm the community of South Padre Island is a haze of condominiums and hotels resting on a faint ribbon of earth.

Because of the storm Jose decides to anchor at the mouth of the bar for the rest of the day and head out into the Gulf that evening. Since shrimping is conducted at night it would be pointless to plow through a rough sea and wait for nightfall out there, rather than in the protection of the bay.

This leaves a long, all-but-vacant afternoon to be disposed of. Having keyed myself up for immediate adventure on the high seas, I’m not too happy with the prospect of a six-hour layover within sight of the shrimp-infested waters of the Gulf. The crew, however, seems delighted. David and Carlos busily begin to clean a few sheepshead that were caught the night before while Jose takes me on a tour of a spotless engine room dominated by a monstrous yellow engine that looks like it is repainted daily. He points out the shrimp hold, which contains three compartments the size of walk-in closets and each capable of icing down a ton of shrimp. Jose then makes an effort to explain the workings of the “rigs,” the generic name for all that hoists and drags and hauls the 60-foot shrimp nets, but it is all I can do to locate the various components and begin to take inventory.

The nets, of course, dominate everything. They are strung and looped in some cryptic order across the cables and lines that support them, but it is impossible, without first seeing the nets in action, to determine where they begin or end or what shape they are meant to assume in the water. Each net is attached in some way to what looks like a section of green shag carpet, and to two massive wooden platforms hinged together like french doors and lashed to the side of the boat. These in turn appear to be operated by a byzantine network of cable and rope and chain which filters through one of the two outriggers and comes to rest, more often than not, in the maul of the omnidirectional winch.

I regard Jose with awe. It would take a master-puppeteer to operate this mess.

“Sometimes it gets all tangled up,” he admits. “They call that a Mexican Sausage. Sometimes you have to come into shore and use a blowtorch on it.”

By two o’clock there are as many as ten boats anchored at the bar along with us. One named the Rosa Lea idles up and ties onto our stern. From high up on its bow the captain carries on a long conversation with the Reverie crew, a conversation whose only English reference points are “Union Carbide,” “Brown and Root,” and “Don’t fool around with Merido or you’re dead.”

But out here on the flat gray water the listlessness is overpowering, and the dialogue finally degenerates into silence.

On the horizon the rust-red hull of an inverted shrimp boat becomes visible as it is towed toward the channel.

“That’s the boat that capsized yesterday,” Jose says. “If they tried to sink it for the insurance they sure didn’t do a very good job.”

Three o’clock. Jose is watching “High Rollers” on his tiny TV in his tiny room. David, having broiled the fish he had cleaned earlier, suggests that I sit down to lunch. He himself does not eat, but he seems to take a keen interest in my appetite. The meal is abundant enough for me to realize happily that I won’t need the Oreos after all. Besides the sheepshead, there is a baked potato and guacamole salad. While Carlos snores in his bunk not three feet away from my plate, David and I attempt a conversation.

Like Carlos, he is from Matamoros, though legally so. He says he has four kids, and that he’s 29, though he looks older, more weathered.

Soon David is asleep too, and I’m stretched out on the canvas covering of the shrimp hold reading about psychological time in The Magic Mountain. The bay is perfectly calm, the boat perfectly still upon it. The captain of the Rosa Lea and the crews of the other boats have also retired, but it may as well be the boats themselves that have gone to sleep. It is one of those afternoons in which serenity is indistinguishable from tedium, and (though I have not yet on this voyage seen a single shrimp) it does not seem presumptuous to infer that a shrimper’s working life is embroidered by just this sort of sluggishness.

At five o’clock, almost on cue, the fleet begins to wake up. Carlos comes onto the deck and urinates over the side. Jose and David follow him out and begin pulling up the anchor and casting off from the Rosa Lea. Within minutes the Reverie, with all its occupants in the wheelhouse, begins to follow the jetty out into the Gulf. The water changes abruptly from the pallor of the bay to the wild opaque green of the ocean. David points to two girls fishing on the jetty in the sandstorm.

“That’s the business!” he says inexplicably.

Jose rubs the sleep out of his eyes. The sky is still overcast and, once we have left the protection of the jetty, the water proves rough enough to impart to my stomach the first gauzy intimations of mal de mer. It will take several hours to reach the fifteen-fathom water in which he wants to make his first “drag.” I ask Jose if I can borrow his bunk.

“Sure, you want something to read?” From a drawer beneath his bed he pulls out a copy of The Panty Salesman. “I’ve got another one I can’t find. It’s about a teach—The Teacher Likes to Do It, or something like that.”

One good thing about The Panty Salesman is that it has bigger print than The Magic Mountain; that seems to be a vital consideration for my mounting seasickness. I read a few chapters to get an idea of its thematic undertones:

“It’s . . . . It’s indecent!” Burt raged, his eyes roaming over his wife’s svelte figure, accentuated to perfection by the soft clinging fabric of the silver-colored romper suit.

Though the book affords me some spiritual solace, it does nothing to calm my mutinous stomach. The view from the porthole in Jose’s room is either gray sky on the upward slopes of the swells or gray sea during the plummet down to the trough. I lose interest in which is which. I lose interest in everything. Even a directory of nudist camps in “Sun Quest” magazine fails to revive me.

Finally I remember the Dramamine. At Jose’s suggestion I also consume a six-inch pile of crackers. By 7:30, when it’s time to set out the nets, my stomach has been quelled and dusk has brought a corresponding placidity to the ocean itself. To the west, where the setting sun is still palpitating behind a bank of clouds, the land that is theoretically fifteen miles away has ceased to be visible, so the horizon now is an uninterrupted circle of water.

Very quietly, as though it is a task that requires reverence, the nets are set out. In an instant the function of each piece of equipment becomes clear. David throws the nets overboard as Jose and Carlos hoist the big doors out onto the ends of the outriggers and lower them, spread at the hinges, into the water. Now it is evident that their purpose is to keep the ends of the nets spread out, as it is the purpose of the hitherto mysterious tickler chains to insure that the entire rig stays on the bottom.

There is a smaller net, only ten feet in length, called the try-net. Jose hoists this overboard next. The try-net will run along in front of the big net and will be checked every 30 minutes to determine whether or not the location is worthwhile. A regular drag with the two larger nets lasts six or seven hours.

“I heard on the news that they’re closing in on Patty Hearst,” Jose says. No one else has anything to say during the entire operation.

When the time comes to inspect the try-net, the sea and sky have grown perfectly dark. Jose floods the deck with a mast light, and it seems suddenly as if we are under the spot-lights on a surreal stage, playing to a vast empty house.

When David unties the bottom of the try-net a veritable bestiary slithers out onto the deck: a big spider crab, sunfish, sea lice, baby flounder, all interlaced with a small population of squirming shrimp. In my twelve hours on board the Reverie this is my first encounter with the prey, but the plethora of life there on the deck is so distracting that I do not even notice the shrimp until Jose begins to sort them out, darting in and out with his fingers among the pile of weird and bristly little fish that together seem to comprise a single gasping organism.

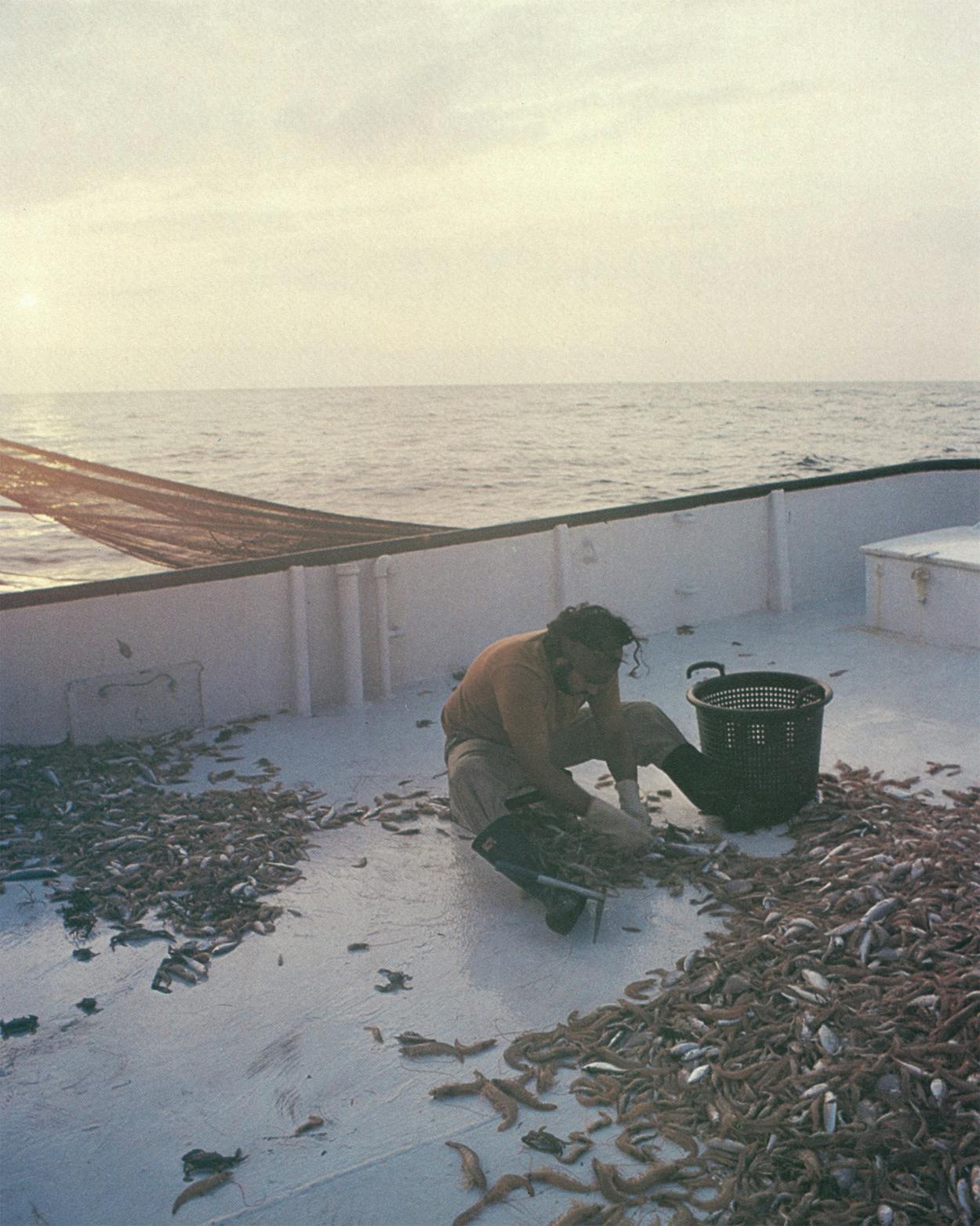

The pile yields about ten or twelve worthwhile brown shrimp and a few “sea-bob”—cocktail shrimp. These are thrown into a bucket while the rest of the pile—the “trash”—is discarded. There is a rustle of carapace as Carlos, using a wooden scraper attached to a broom handle, sweeps them through a hole in the side of the boat.

Under the deck light the shrimp are a beautiful translucent rose color. They look like fetuses, like creatures who have just come fidgeting into life instead of creatures who are now taking their leave of it. Carlos puts on his gloves and squeezes their heads off between his thumb and index finger, with the same motion he might use in dealing cards. Their legs quiver mechanically for a while afterward, then their tails tuck inward until they have assumed the universal position of dead, saleable shrimp.

The try-net is lowered again. Jose seems satisfied enough with the output of the first net to stay on course.

“Well, I go sleep,” says David, smiling at the prospect.

I follow Jose to the wheelhouse and watch the hypnotic green sweep of the radar screen.

“You know that Woolco in Brownsville over there by the new post office,” Jose says. “Well, I live behind that. I’ve got 30 years to pay off that house. I bet by the time I get through with it it’ll cost me $80,000 or $90,000.”

Last year, Jose says, he made $17,000. The year before he made $19,000. He and David split the shrimp profits 60 40 with Boudreaux, and out of that 40 per cent Jose gets slightly more than half.

“I have to make $200 a week to get by,” he says. “If I worked on shore I wouldn’t make it. Besides, I’d rather work out here. If I got a job on land I don’t think I could get used to it. I guess once you get used to fishing that’s it. Even if I don’t have to go out, I come down to the boat. You get a habit, you know?”

He peers out through the porthole and, as though he has actually seen something in all that darkness, makes an adjustment on the fathom meter.

“When I started fishing in ’55 there were a lot of shrimp. You could go down south—it was easy to stay away from the gunboats. Now they got new gunboats with radar and everything.”

The gunboats are there to keep foreign shrimpers out of the bountiful Mexican limit, an area which extends twelve miles out from shore all along the coast. When an American boat wanders into this limit—or when it is close enough for the Mexican authorities to say it has—it is impounded and assessed a ransom commensurate with its value. Recently one owner of a boat had to pay $24,000 to get it back.

When the gunboats were still U.S. surplus World War I minesweepers it was an easy matter for a shrimp boat captain to haul in his nets and move on as soon as he saw one lumbering toward him on the horizon. These days, with swifter and better-equipped gunboats, it’s wiser not to take chances.

Shrimpers still go south, though, all the way down to Campeche where the shrimp are plentiful in the early months of the season, even outside the coastal limit. But it’s a long trip—the boats sometimes stay out for months—and now that the cost of fuel is so high it is problematical whether a profit can be made on such an excursion. So for the most part the boats operate along the Texas coast, sometimes ranging as far north as Louisiana but seldom staying out for more than a week or two.

When it is time to check the try-net again, Jose glances at the radar and turns on the pilot before leaving the wheelhouse. This time the net yields an abundance of small stocky crabs. Jose picks one up to show me.

“This is a bottle crab.” He nonchalantly pulls off one of its claws. “You can take this claw and cook it.” He seems to consider doing just that, but instead he throws the maimed crab and its appendage back into the water.

The big nets will not be brought in until 2 a.m., six hours away. Since there are only three bunks in the Reverie Jose suggests I go to sleep in his while he takes the first watch. Later, after the nets are checked, I can resume my slumber in David’s bunk during his watch. This sounds complicated, but I’m too tired to sort it out. I have a bedtime snack consisting of about a dozen boiled jumbo shrimp and drift off to sleep on billows of nausea.

Soon after that a voice in an otherwise forgettable dream croons, “Time to check the nets!” I sit up, hit my head on a low ceiling, and put my consciousness into order before stumbling bleary and homesick out onto the brightly lit deck. The water is a little rougher than it was before, and it takes a bit of prowess to avoid being pitched over the thigh-high gunnels into a spooky black sea.

The two nets are winched to the surface simultaneously, then one after another they are hoisted over the deck. The length of green carpet whose purpose I could not determine earlier is revealed now to be a swollen bell-shaped repository into which all the denizens trapped by the wide mouth of the net have been funneled. Called a chafing net, it serves primarily as a guard against sharp shells and barnacles.

David unties a rope underneath the chafing net and steps back to avoid the gush of creatures that slides out of it. The sight is awesome and not a little creepy. It seems that the net is giving nightmarish birth to a million offspring all clamoring for survival, all of whom will be denied. When the other net is emptied on top of this pile the deck is laden with a grotesque mountain of beings three feet high and six feet in diameter. This time there are sting rays, large flounder (which will be saved), cabbageheads whose gelatinous bodies have been ruined in the mesh of the nets, squids, ribbon fish, hundreds of small sunfish and croakers, blowfish, crabs, and scores of the rock shrimp whose primitive, hard-to-peel shells make their saleability negligible.

The entire ceremony is conducted in silence. David walks around the pile shaking the nets free of clinging sealife, casually scrunching crabs underneath his rubber boots. Then the three of them don their gloves and pull up little milking stools and set to work with solemnity. The shrimp heads fall at such an astounding rate between David’s mercurial fingers that the task almost qualifies as sleight of hand.

I soon discover there is hardly any thing worse for encroaching seasickness than watching people pull the heads of of twitching, slithery sea creatures, and I am forced to retire to the dining table inside the cabin, take another Dramamine, and try not to think about shrimp. No chance. Over the sink the silhouette of a scrub brush against the porthole assumes the shape of a prawn, with bristles for legs and a long curved handle for a tail. From the shortwave in the wheelhouse there is a constant substatic drone, conversations between shrimp captains punctuated with the same plaintive drawl of “Ay, chingaaa!”

After a while Jose comes in and fills a mixing bowl with cornflakes.

“We got 90 pounds that time. If we can get another basket or so on the next one we’ll be doing all right.”

At 3 a.m. I crawl into David’s bunk and go to sleep again. I dream that I am speaking to a friend, and that my words become little crustaceans that tap out the message with their feet in an elaborate chorus line.

When I am awakened again it is past 8. Though the boat is still jostling a little, the movement is less threatening by daylight. And when I walk out onto the deck I discover that it is a remarkable daylight indeed that has chosen to invest the Gulf of Mexico this morning. The world is as gray as Jose’s sweatshirt: the Reverie is encircled by a fog that fuses with the water at the horizon, confounding any human measurement of distance. Near the stern of the boat a dolphin slices noiselessly through the water, its dorsal fin festooned with a sprig of seaweed. Then, from either the fog or the water—it is impossible to tell which—come two dozen more, some of them spiralling completely out of the sea in anticipation of the feast. A flock of sea gulls abruptly swarms over the nets, breaking the calm.

The first net is opened and two small sharks tumble out. Carlos picks them up by the tail and, with an almost studied indifference, slams their heads against the side of the boat and throws them overboard.

The other net is bulkier, it bulges out at odd angles. Seeing its shape, David peeks inside.

“Big chark!” he says.

When he opens the net a seven-foot bull shark unravels from it. The fish lands on its back and is immediately buried by a maggotlike layer of smaller animals. Only the pink underside of the shark’s jaw and its wide pectoral fins remain uncovered. It does not move. A solitary sea louse lies undisturbed inside its mouth. In a gesture of bravado David fingers the shark’s gums, then picks up the broomlike scraper and puts the flat wooden end between the jaws. Still it does not move.

Suddenly the shark comes to life. In one frantic motion it swallows the sea louse, jerks itself up, and thrashes over on its stomach, scattering the crustaceans like bedclothes. From its new position it futilely goes through the motions of swimming, taking random swipes with its mouth at the pile of shrimp encircling it.

Soon the shark quiets down, as though it is waiting to see what will happen. David slips a rope over its tail and Jose begins cranking the hand-winch. The shark’s bewilderment is profound: with its mouth it tries to reach back to the tail but its whole body is already following the tail upwards. The object is for Jose to lower the rope just as David shoves the shark over the side with the scraper. But by now the shark has come to full life: once David has shoved it once or twice it can feel the momentum and seems to rally, maybe thinking that in this wild swing through the air it is back in the water, ready to fight on its own terms. The spectacle is exhilarating, surreal. With a shudder I realize that the shark has locked in on Carlos and me as its targets: when it swings near us it somehow lifts up the front part of its body in midair and works its jaws furiously in a vain attempt to grab us where we stand, beyond the reach of its arc.

David shoves at it, pummels at it with the scraper, retreating and advancing with the sway of the animal. It spins and swings and thrashes out at him like some ghastly piñata.

Finally it swings out far enough over the water. Jose lets the shark fall down below the gunnel so it cannot jump back into the boat but he stops its descent an inch or so before the shark’s snout reaches the water. With a last nasty gesture, David takes his fish knife and slices open its stomach. Then he signals to Jose to let it drop. The shark disappears with an erratic but irredeemably downward stroke into the dark green water.

With the shark disposed of, the crew sets about the quotidian task of sorting and heading the shrimp. While they do so I assemble a pile of dead croakers and toss them to the dolphins that have gathered at the stern. When, finally, David opens the little door on the side of the boat to shovel out the unwanted fish, the dolphins arc from the water en masse at this familiar sound and converge at its source.

There follows a sedate feeding frenzy. Through the water I can see the dolphins examining each piece of fish, seeming to decide if they really want it or not. Mingled with the familiar bottlenoses are several members of a different, rarer species with freckled mahogany skin called spotted dolphins.

After the deck is cleared and the shrimp put into the hold, the anchor is dropped and the nets are hung up for the day. While Jose cooks, the rest of us eat a breakfast of refried beans, eggs, and Spam. David and Carlos have squid for dessert. I pass.

The meal progresses in silence until David takes a long drink of Orangeade, belches, slaps his stomach, says, “Feel good!” and takes two steps across the hall to his bunk.

It is clear that the crew of the Reverie and I are on different schedules. By mid-morning I am again the only one awake, alone on the shrimp hold with Thomas Mann. There is no sound, no sound at all except for the creaking of the rigging and the occasional soft “puhhh” of a breaching dolphin.

A long day ensues in which the time is measured against nothing but the number of pages turned in my book and the slow movement of a hazy sun burning through a thoroughly overcast sky. I try to think about shrimp the way Melville thought about whales, but they remain impervious to any romantic considerations. There is no Great White Shrimp, no Lost Shrimp Graveyard, no oversized carnivorous shrimp that pull shrimpers under with their feelers. No, if those little crustaceans are a worthy prey, it is not because they are monstrous or honorable or evil or inscrutable, but because it’s just so damn much trouble to dredge them up out of the ocean and into the shrimp cocktails of the world where they belong.

Their lives, their little joys and sorrows, are forever beyond us. But the existence of a shrimp does have an attractive lackadaisical rhythm to it. Hatched deep in the Gulf, they are soon swept by the tides into the shallow lagoons and estuaries that pockmark the coast. There they reach the age of consent and begin the long swim back out to the Gulf where, at night, especially when the moon is full, they “run” across the ocean floor, feeding on algae and mollusks and smaller crustaceans and anything else they can manage to get into their complicated mouths.

The nets go out again just as the sun sets behind a distant offshore drilling platform. Again the crew works in silence. Once or twice a day Jose and David will have a conversation extraneous to the operation of the boat, but neither of them seems to speak to Carlos except on the rare occasion when an order must be given that cannot be expressed by a gesture. But this speechlessness is not due to any ill will or condescension. David, especially, seems to feel a genuine paternal affection for Carlos, manifested in furtive, encouraging smiles delivered across the dining table. No, the silence is more likely imparted by the stillness of the environment. It is simply easier to blend in with that stillness, to accept its cadences.

Carlos himself seems to walk about in a persistent daydream. For the past two days he and I have been playing a highly subtle game of hide and seek, with me continually catching glances of him exiting parts of the boat I have just entered. This may be due to paranoia—for all I know, no one has really filled him in on what I’m doing here, and he may see me as a threat to his delicate national footing—but it is probably just a natural shyness. At seventeen, he has the valuable gift of being aloof without giving offense.

Winston Churchill, I read somewhere, could not sleep unless he was able to wake up in the middle of the night and switch beds. I have the opposite problem. When Jose wakes me again at 2 a.m., this time with a little more effort, I follow him dutifully out onto the deck and take notes as another pulsating mass of shrimp is delivered up from the sea. There they are, all the standard sea beasts wildly flapping their gills and flailing their pods. But I’m jaded, I’ve seen it before. Twenty-four hours ago, when the crew was looking the other way, I was bending down like Saint Francis of Assisi, picking up expiring crabs and tossing them into the water. Now I kick them off to the side with my shoe, aiming them like hockey pucks at the rectangular hole in the side of the boat but not bothering to move in for the score. There are just too many of them to deal with.

Jose, perhaps sensing my flagging interest, demonstrates the sublime distinctions between male and female shrimp. Sure enough, fleetingly visible in a tangle of waving legs, there are the relatively standard indentions and protuberances on the ventral side of the long head.

Above us the cloud cover has drawn back for the first time, and now a nearly full Palm Sunday moon is visible off the mast, as is a lone sea gull fluttering like a moth in the deck light while the crew returns to the routine of sorting and heading.

Later, concluding that it is pointless to sleep, I join David in the wheelhouse during his watch. He sits in the captain’s chair and keeps the wheel in position with his feet. He acknowledges my presence with a welcoming gesture, but in the dim, forlorn green light of the wheelhouse, conversation is almost unthinkable. Above his head the shortwave continues its uninterrupted stream-of-consciousness in Spanish. The men who speak over it seem to me to be talking to themselves, like the way dying pilots in movies talk into dead radios. Every so often David smiles to himself, a lateral smile that cuts deep into the side of his face and hinges his keen narrow eyes closer together. I can see that while the absolute openness of the Gulf riles and terrifies me, it lulls him. I think of the calm, grim look that was on his face when he cut open that shark, as though it were a ritual he was fulfilling. It seemed to me at the time a cruel and unnecessary act, but when he performed it he was in touch with something I was not. Comprehending neither the signals from the sea nor the voices from the shortwave, I sit and watch him, and realize that he is surrounded by communication.

The next morning the sky is overcast again, the air is cold, and the Reverie is pitching more than ever. The nets reveal the usual potpourri: a few small hammerhead sharks and what will turn out to be about 65 pounds of shrimp.

“You should be out here tonight when the norther really hits,” Jose says, taking note that my face is as green as the water.

The nets are folded, the doors lashed again to the side, the outriggers brought up for the trip back to Port Isabel. David cooks breakfast, producing a perfectly fried egg while standing at a 45-degree angle. My own taste runs once again to crackers. I find that if I sit perfectly straight at the table, arms outstretched and hands gripping the edges, I stand a good chance of withstanding the three-hour trip back to shore. Provided, of course, that I can keep my eyes averted from the yolk of David’s egg. I mutter a little prayer that he will eschew his morning squid or, failing that, that he will not put catsup on it.

But after a while the effectiveness of my position begins to diminish, and I stand up, aim for the wheelhouse, wait for the next forward pitch of the boat and tumble into the radar screen just as Jose lifts up his sweatshirt to show me his knife scars. Curiously enough, this enormous fleshy fault line running across my host’s chest checks my nausea instantly.

“Three hundred and sixty stitches,” he says with understandable pride, for the thing looks like it was carved by a scimitar. “I tried to break up a fight. Guy cut my liver in two. They said I had only four hours to live.”

This leads us to a discussion of the hazards of shrimping. Jose says that in February a rig man in another boat fell overboard in a sea like the one we’re now experiencing. Several boats, the Reverie included, searched all night with flares but the man was never found.

“It don’t matter if you’re a good swimmer. If it’s rough and dark they’re not going to find you. Last November another rig man got drunk and fell overboard. He drowned, but they found him when they pulled up the net.”

Soon we can see the bar. I look for the famous Port Isabel lighthouse but it is obscured behind a series of high-rise hotels. We are returning to the docks with 500 pounds of shrimp. They will be suctioned from the hole by a giant vacuum that runs like a pipeline into a nearby warehouse. There they will be sorted; in their afterlives they will be known as cocktail, medium, or jumbo shrimp. Some of them will be breaded, some of them will end up in frozen packages decorated with pictures of smiling fish wearing sea captains’ hats, and the rest will go to restaurants and fish markets and be sold for what shrimpers feel is less than they’re worth.

When we reach the bar we notice that not much has changed over the weekend. The capsized shrimp boat has not yet been righted, but rests like a beached whale against an available mooring. The sandstorm that accompanied our departure has not abated in honor of our return. And the radio says they’re still about to nab Patty Hearst.

______

Down the Hatch

Seventeen good places to get fresh shrimp

There is no record that anyone has ever tamed or otherwise domesticated a shrimp. Doubtless they would make indifferent pets in any case. Although the town of Aransas Pass has erected a large statue of a shrimp, that crustacean is not their high school mascot, for obvious reasons: cheerleaders and football players alike would have difficulty rallying to win a game for the fighting Shrimp.

No, shrimp do not have even the occasional winning qualities of cows or chickens. They are legion, countless, impersonal. Their most important characteristic is that they are good to eat, but even this distinction is best observed in numbers. We seldom hear people talking of having eaten a particularly tasty shrimp the other day. The point of eating shrimp, after all, is to eat as many as is possible or polite, and to eat them fresh.

Where, in Texas, might one do that? One’s first instincts might be to journey to the coast to buy shrimp fresh off the shrimp boat. Shrimpers can be found from Port Arthur to Port Isabel, and most are glad to sell small quantities at negotiable prices to shoppers adventurous enough to make the effort. Nearby fish markets like Seven Seas Fish Market in Port Aransas also sell virtually off the boat. Seven Seas prices for large shrimp are $3.50 a pound; for medium shrimp $2.95 a pound. While romantic, however, such expeditions may not be advised. By the time you get your batch home, it may be only as fresh as the shrimp in a good market.

In Austin the best places for shrimp are the Capital Oyster Co., 219 West 15th (order the Cajun boiled shrimp: $2.00 for six, $3.25 for twelve); the Sandpiper, 2700 West Anderson Lane (try shrimp Mariniere: shrimp and mushrooms broiled in a sophisticated sauce); and Mike and Charlie’s, 1206 West 34th (get the shrimp Paraiso: giant Asian shrimp split down the middle and broiled in garlic butter).

Ironically, Corpus Christi is not one of the best places in Texas to get good seafood, but you won’t be disappointed if you stick to Ship Ahoy’s two locations: 6102 Ocean Drive and 1017 North Water. The second location has a large variety of shrimp dishes. Another reliable standby for a fried shrimp platter is the Black Diamond Oyster Bar, 5712 Gollihar.

Dallas’ best shrimp-eating spots are Maison Orleans, 7236 Greenville Avenue (various shrimp dishes, plus a Sunday shrimp boil with all you can eat for $4.75); and Sea Coast Fish Market, 5719 West Lovers Lane (a fine fish market where you can buy cooked, ready-to-eat jumbo shrimp for $5.20 a pound or uncooked shrimp at $3.19).

In El Paso Amen’s at 1201 North Mesa offers giant Malaysian shrimp sautéd in butter, garlic, and parsley. It’s superb and at $8.50 it should be. Comedor Virginia’s at 715 North Xochimilco in Juarez serves shrimp Virginia, a perennial border favorite.

Bill Martin’s Second Edition at 4004 White Settlement Road in Fort Worth offers plain old unpeeled boiled shrimp: for $2.25 you get a Half Catch (17 to 20 shrimp) and for $4.25 you get a Whole Catch (about 34 or 40 shrimp). The Old Swiss House, 5412 Camp Bowie, has a nice dish called Spanish shrimp (Asian shrimp broiled in bread crumbs, herbs, and butter), but ask for it—it’s not on the menu.

Shrimp in Houston can be had at the Big Mouth Frog, 2727 Crossview, where for $3.95 you can get a platter of about 25 unpeeled boiled shrimp. Glatzmaier’s Seafood Market, 416 Travis, lets you select your own shrimp (and any other seafood) from the case in front: a do-it-yourself fisherman’s platter. Both Benihana of Tokyo and The Happy Buddha offer shrimp cooked at your table, Japanese show biz style.

Practically every restaurant in San Antonio buys their shrimp from Polunsky’s market, so differences in quality are slight. Kangaroo Court, 512 Paseo del Rio, and Naples, 3210 Broadway, offer interesting shrimp dishes, but in San Antonio one might be better off sticking with Chinese food.

- More About:

- Hunting & Fishing

- TM Classics

- Shrimp

- Longreads