The story of the rise and fall of Mario Cantú, like the slivers that fall when a cascarón bursts atop one’s head, calls to mind brightly colored bits and pieces of a moment that no longer exists. Mario, who died of complications from cirrhosis on November 9 at the age of 63, perhaps none too soon, was himself a cascarón, inside of whose head and within whose body lived San Antonio’s Don Corleone, Pancho Villa, and Cesar Chavez—and toward the end, one of the Mission City’s maddest saints. He was a restaurateur, a revolutionary, a criminal, a town character, and a friend—the kind of guy who made an impact on your head, leaving a stream of multicolored detritus in his wake. He was the last spokesman for a generation of Mexican Americans whose outlook on San Antonio had been formed in the years between the Mexican Revolution and World War II. In that era, before military bases became key to the city’s economy—and before the rush of Anglos in uniform—San Antonio was a northern Monterrey. In Mario’s view Mexican Americans were not interlopers in the life of either the United States or Mexico; they were the captives of both nations.

He began life as Mauro Cantú, Jr., the son of a universally beloved small grocer who kept a store at the corner of Pecos Street and what is now Interstate 35, where San Antonio’s downtown abuts its heavily Hispanic West Side. It was perhaps symbolic that young Mauro’s Anglo grade-school teachers could not pronounce his name and that before long, he was known, both to them and to policemen, simply as Mario.

As he told the story to me, he was first arrested at the age of fourteen, when, because he wanted to learn to be a writer, he stole a typewriter from an office near the grocery store. His debut onto police blotters led to his enrollment in a program for juvenile delinquents, headed and taught by a man named Damaso Hernandez, under whose tutelage Mario became conscious of the society and the culture that he would later exploit for both profitable and political purposes.

Adolescent Mario soon noticed, for example, that people were fleeing from the central city to the suburbs. They would no longer need a corner store, Mario told his dad. Since many of them still worked downtown, he argued, former West Siders would need a lunchtime restaurant instead. As a concession to his eldest son, Mauro Senior opened a food counter at the grocery store, selling rotisserie chickens—and a San Antonio scene took its first tentative steps.

Mario’s first came to the notice of the in crowd during the late fifties. From the beginning, the restaurant served blacks, the first major San Antonio eatery to do so, says Romulo “Chacho” Munguía, a retired printer and politico. But its early notoriety did not survive into the sixties, because its moving spirit spent most of the decade behind bars, following a 1962 conviction for a heroin sale. Transferred to the federal prison at Seagoville for the last part of his sentence, Mario studied culinary arts at El Centro College in Dallas. Caterings by the restaurant thereafter featured ice sculptures on Aztec themes and the menu for which it became rightly famous.

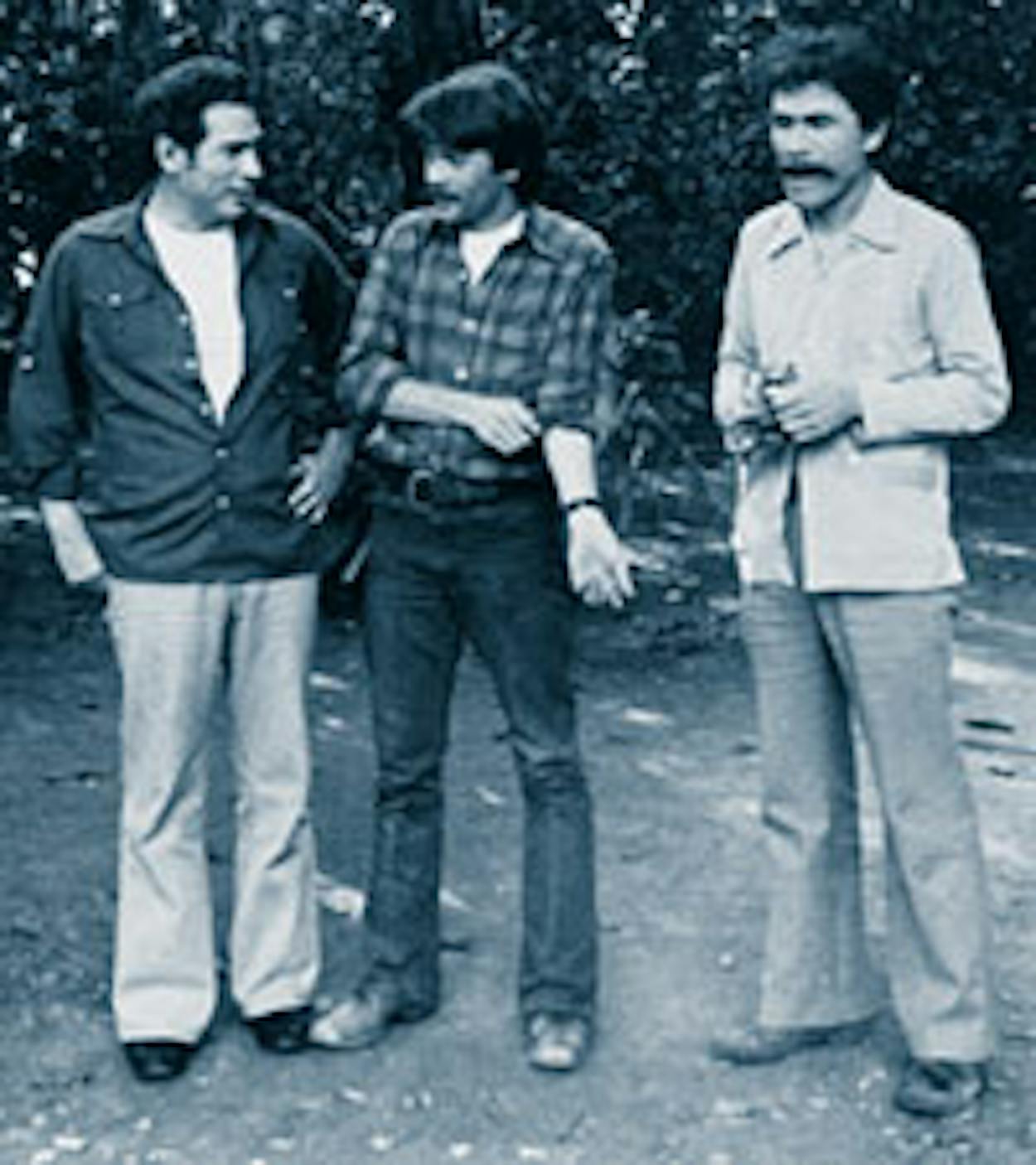

Out of prison in 1969, Mario was soon a distinctive figure in the burgeoning movement for Chicano rights, both because he had the money to finance his ideas and because they occupied a unique space among Mexican American thinking of the time.

For Mario, a “Mexican American” was someone of Mexican ancestry who was seeking to reform an Anglo-dominated society. He called himself a Chicano, a term that he took to mean “Mexican and American” in a very revolutionary sense. Mario believed that the spirit of Mexico had not been freely expressed since the days of the Conquest, and that unleashing it would bring down culture and politics on both sides of the Rio Grande. And he did what he could to unleash it.

During the seventies the restaurant was the only place in town to be, a hotbed of political coalition building and intrigue. It also served up exquisite Mexican fare, as authentic as the birthplaces of its immigrant cooks. The signature dishes at Mario’s, all still served by the restaurant that today bears the name (though it is operated by his younger brother Hector at a new location on Fredericksburg Road), included mollejas, or “sweetbreads” (from glands found in the neck of cattle); puntas de filete en chile chipotle, a dish whose sauce is its lure; and abujas, a Mexican rendition of ribeye steak, which required the restaurant to hire its own butchers to prepare a cut not known in American cuisine. Mario’s also made a name for itself with tripitas, a dish from beef intestines; and hongos con chorizo, or mushrooms with picante Mexican sausage. Bankers and Anglos-about-town, Mexican American agitators and pols, drug runners and G-men all flocked to the place, which seated nearly four hundred people, employed a twelve-piece mariachi band, and was open around the clock.

When Mexican president Luis Echeverría visited San Antonio in 1976, other Mexican American leaders flocked to his entourage. Mario staged a demonstration, assailing el presidente as a CIA agent and asesino, or murderer, because of the killings of student protesters in Mexico City in 1968. Echeverría lunged at Mario’s picket sign, denouncing the restaurant operator as a “fascist.” The charge, like most of those by Mexican politicians of the time, was anything but true; Mario, who claimed descent from Lucio Blanco, a Tamualipas hero who implemented Mexico’s first agrarian reform, was at least as much a part of Mexico’s revolutionary family as Echeverría himself.

By the time that Echeverría assaulted him, Mario was secretly aiding Florencio “Güero” Medrano, an unlettered peasant trained for revolution in China who was trying to start an uprising near Oaxaca. Among other things, the Alamo City restaurateur had procured a convertible and filled its trunk with M1 carbines. He dressed a waitress in a wedding gown, painted “Just Married” on the car, and drove to Mexico City, confident that border guards would not molest newlyweds on honeymoon.

But he could not escape trouble with the law. Even before Echeverría came, a team of agents from the Immigration and Naturalization Service had knocked on the restaurant’s door one noontime, planning a sweep. Mario had refused to let them in. While la migra went to find a judge who would grant a warrant, Mario asked lunchtime regulars to accompany undocumented employees out the door. The federal agents arrested only three, two of whom, in exchange for residency status, later gave testimony against their patrón. The third, a waiter, refused to cooperate and was himself charged; Mario paid the waiter’s legal expenses in a case that, before it was won, went all the way to the U. S. Supreme Court. But Mario had no such luck: He was convicted of harboring illegal aliens.

His sentence was probated, but that left him exposed when, in 1978, he appeared on television as part of a peasant uprising that Medrano led. Probation authorities scheduled a hearing and Mario fled to Paris. During his self-exile, public sympathy built for his defense. Archbishop Patrick Flores had spoken for him in a letter to the presiding judge, and Mario engaged leftist lawyer William Kuntsler of New York to prepare his defense. When he returned some fourteen months later, the judge sentenced him to a mere six months in a halfway house.

But during Mario’s stay in Paris, Medrano was killed by Mexican pistoleros, and the Chicano movement headed down the road to becoming the tame lobby that it is today. Rebel Cantú was left without a cause. Within a year, he was enraptured by a scenario in which the United States—an imperialist power inside its own borders, in his view—was brought to its financial knees by the looming traffic in illegal drugs. “Cocaine is Latin America’s atomic bomb,” he told me.

Mario’s observation, now being put to test by Colombian guerrillas, was critical to him in ways that his friends, me included, were too fearful to recognize. The plain truth was that Mario probably never gave up smuggling. If it had been heroin during the sixties, it had become marijuana during the seventies, and it became cocaine during the subsequent decade. A Colombian, he later told me, had come to San Antonio to recruit him for the trade, bringing with him two kilos of coke, a sample of his product line. The agreement, or maybe Mario’s plan, was to extend the market to France. He returned to Paris, where he opened Mario’s Papa Maya Restaurant, a place so hip that a French gastronomic society created the Golden Tortilla Award in order to bestow honor on a foreign cuisine. While in Paris this time, if Mario did not distribute cocaine, he consumed it—too much of it, a kilo during a single month, he confessed. The thirty-day rush melded the wires in his brain, though in a way consistent with his genius for imagining things. French mental health authorities pried him from the second-story room where he lived, but the always-daring Mario escaped from the asylum where they had put him away.

Back in the States, Mario opened forgettable restaurants under a variety of names: one in Austin, three in San Antonio, and another in New Jersey, where a daughter lived. All except the current Mario’s failed in part because Mario had concocted “Cosmic Chicano Cuisine,” a sort of cross between nouvelle and Mexican fare that was too far ahead of its time, and in part because none of his intimates could manage the addled mind that now squirmed inside his skull. Eschewing Karl Marx and the Magón brothers, precursors of the 1910 revolutionaries, Mario became a follower of the inscrutable Teilhard de Chardin, a controversial Jesuit theologian. He saw spiritual signs everywhere. Time and place were no longer exclusive in the physics that he pursued: Jesus had been crucified in Jerusalem, yes, but also on the site where the old Mario’s had stood. When the pope visited Cuba, Mario had to make his way to Havana because the Holy Father had, of course, chosen the venue to meet with him.

Mario in his later years was convinced that there is a mystical connection between the names of things and things as God must know them. His model for this article of faith was naturally the true or divine origin of the term “Chicano.” In one of our latter-day conversations, he reminded me that the term comes from Mexica, the language of the Aztecs, who referred to themselves as “mexicanos.” Spanish speakers pronounce “mexicano” in the way that we all know, with a j or, in English, h sound, but the Mexica—remnants of whom still live and speak the language—pronounce the word in a way that Spanish, lacking a sh sound, cannot: “meh-she-cano.” Mario seized upon the “sh-e-e-e.“

“What is the first sound that a newborn child makes?” he asked in his always-rhetorical way.

“It cries,” I muttered, knowing that since Mario was teaching, I somehow had to be wrong.

“No, crying is a sound induced by a doctor,” he lectured. “The first sound that a child makes on its own is when it urinates, and when it urinates, what sound does it make? Sh-e-e-e-e,” he said.

For Mario such speculation was only an opener. “And what sound is made,” he continued, “when the planets circle around the sun?”

Mario had come to my former home in Dallas to tell me that the planets in their celestial orb sing the same sound that mortals hear in the faithful, untraduced, and original pronunciation of the word “Chicano.” For Mario, being a Chicano, or Sh-e-e-cano, was to be a chord in the harmony of the universe. Even when his mind was soaring into such nonsense, Mario was establishing his role as a Mexican American visionary. The niche that he created for himself cannot be legitimately claimed by anyone else—because nobody ever conceived of his people’s role in terms as grand, or grandiose, as he.

In the years since Mario went mad, I have often wondered if his fondness for me may have derived from his picture of the region as Mexican and American. By his standards, Texans had to know Mexico to know their own place in life. Just as, by hanging out in open-air markets in Oaxaca and Veracruz, he had learned the ancient secrets of Mexican cuisine, he expected other Texans to go to Mexico for apprenticeships in their pursuits. In Mario’s mind, I suspect, I was an Anglo who had made the grade by formulating something of a binational perspective on Texas.

It was not that Mario, in all of his agitation for Chicano Power, was ever hostile to Anglos—far from it. He was hostile to what might be called American triumphalism. He believed that residents of the former Mexican territories of the Southwest should see themselves as heirs to Mexico, living on land that Mexican authorities had abandoned and gringo opportunists had mindlessly occupied.

The final breath of the era in which San Antonio was a Mexican city probably came half a dozen years ago, with the demise of the city’s Centeno supermarkets, losers to the Anglo-run H-E-B. Mario commemorated the event with Eloy Centeno, the family patriarch; both men engaged in a short standoff with authorities, refusing to surrender a plot of land. They were descendants of the aboriginal inhabitants of Texas, they said, who could not legally be dispossessed of ancestral rights.

His last years were times of madness and trouble, though, as always, he was buoyed by optimism and outlandish schemes. Like most of his friends, I began avoiding him; several who could not became unwitting members of a new fraternity, composed of people who had called the police to get Mario out of here. His death came to me as a great and merciful relief, a deliverance of Mario—and me—from a relationship that had become a seance with regret. But even as I spoke a eulogy for him at San Antonio’s dimly lit San Fernando Cathedral, he was not entirely gone. Mario’s ideas and idiosyncrasies will haunt me and a few other old friends until our hearts too are as still as his today.