This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The passengers on the plane to Midland take a peek at the old codger in the suit, cowboy hat, and $600 boots as he settles into his aisle seat and beckons with his only arm to the flight attendant.

“Yes, sir?” asks the young woman, cute as a fishing fly.

“Ma’am,” the man says in a high-pitched drawl, “I think I’m going to have to have me a window seat . . . real bad.”

“The flight’s full, sir, but I’ll try to find one for you,” the flight attendant replies. She is about to move on, but something about this quaint-looking man, with that solemn face and single arm, keeps her feet planted. As with nearly everyone who comes across Bob Murphey for the first time, she can’t stop staring at him. At this moment, he resembles a down-on-his-luck rancher who is dressed for a final visit to his banker.

The innocent young woman leans down. “Is there a reason,” she gently asks, falling right into his trap, “why you need a window seat?”

The old man’s eyes squint. He slowly tilts back his hat and points to his cheek, which bulges with a wad of tobacco. “Ma’am,” he asks, his voice as slow as a cow making its way toward the barn, “I’ll probably need to open the window and have me a spit before this flight is over.”

There is a moment’s silence. And then, like a schoolgirl, the flight attendant starts giggling. She puts her hand to her mouth and giggles louder. When she comes back a little later, still giggling, and asks him if he wants something to drink, he says coffee.

“Black?” she asks.

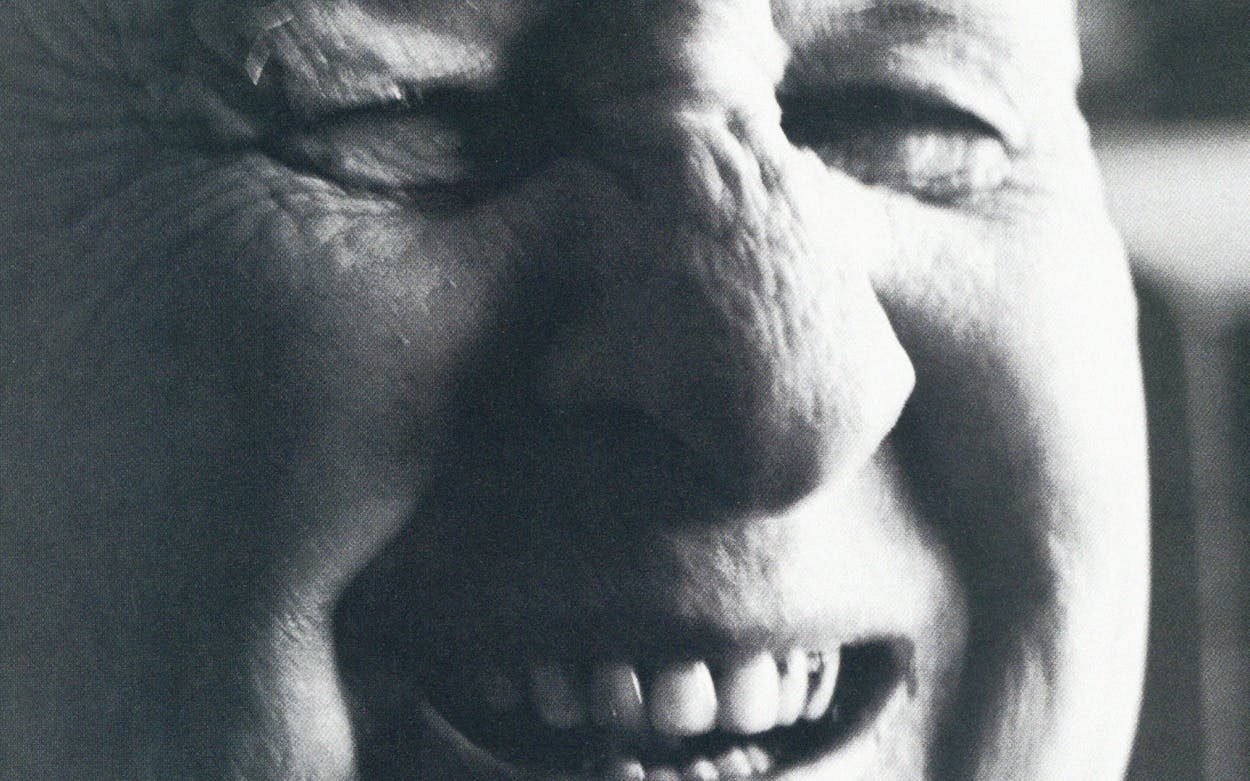

He leans back to think. “What other colors you got?” he asks, and the woman keeps giggling as she makes her way to the galley. By now, everyone around 68-year-old Bob Murphey is grinning widely, like dogs getting their bellies rubbed. With just two very old jokes, the most popular after-dinner humor speaker in Texas has won over yet another audience, an act that he has been pulling off with an ancient deadpan delivery for more than forty years. It is doubtful that anyone has spoken to more groups of people in Texas than Murphey, a former district attorney and volunteer fire chief of the East Texas town of Nacogdoches. With his collection of cornpone tales about good ol’ boys and farm women, Baptists and highway patrolmen, revenue agents and coon hunters, he evokes a portrait of a rural life on its last legs, of a faintly ridiculous but endearing group of people who are rooted to a land that holds little except droughts, dry oil-well holes, and cattle that won’t get fat.

They are stories about little towns where the imprint of civilization was usually no more than the dust kicking up behind someone’s ear.

“I don’t know if country humor will last past another generation,” says Murphey, glancing at the people on the plane. “I wonder if, thirty or forty years from now, people will even understand what it was all about.” He pauses to wipe a little tobacco juice off the side of his mouth. “It’d be a dadgum crying shame.”

This afternoon, Murphey is headed for Odessa to speak before the monthly banquet of the Permian Basin Chapter of the Texas Society of Certified Public Accountants. He makes at least sixty of these speeches a year, two thirds of them in Texas. A few years ago, before slowing down, he was giving nearly one hundred speeches a year. In his office are more than three hundred pins sticking in a Texas map showing the towns and cities where he has spoken. He has talked before undertakers, ditch-digging-machine salesmen, milk producers, fertilizer experts, and meter readers. He has spoken in New York and San Francisco, in front of Fortune 500 executives and political leaders. Yet no matter the audience, the speech is always the same: a hodgepodge of colloquial stories, all of them told in no particular order and with no obvious message except to make everyone laugh.

In Odessa a smiling accountant is waiting for Murphey at the airport. Like a rustic Caesar preparing to greet the masses, his shoulders erect and his jaw filled with a new plug of chew, the five-nine Murphey struts out of the plane with the clunky, pinched-ass walk universal to men who wear heavy cowboy boots. He puts down his briefcase—which holds only a pair of socks, boxer shorts, one red tie, and a shirt—shakes the accountant’s hand, calls him an “ol’ boy,” and when asked how his flight went, bellows, “Like a cattle car.” The man throws back his head and roars. Riding to the hotel, Murphey says he is reminded of a story about the best hotel he ever stayed in, which happened to be in San Angelo. The house detective there knocked on his door late one night and gruffly asked, “Do you have a woman in there?” Murphey replied, “No, I don’t have a woman in here,” whereupon the door flew open and the hotel detective threw one in. The accountant, laughing so hard that the veins on his forehead stick out, nearly swerves into another lane.

It is impossible for a yarn-spinner like Bob Murphey to move through even the smallest event in life without being reminded of a story. “He’s got one of those danged photographic memories,” says his wife, Nada, a droll woman who rolls her eyes and calls her husband Murphey. “He remembers every funny story he’s ever heard. Good Lord, I can’t bring up a thing at the kitchen table without Murphey telling me ten stories about it.” In Murphey’s world, literature and culture certainly have their place, but storytelling is a high art, a way of preserving tradition and enhancing a plain man’s appreciation of the life he must endure. Though lacking in grammatical finery, his language conjures up such rich images that the comic effect is almost hypnotic. “I’m only going to tell you stories,” he reminds his audiences. “I ain’t gonna sing. Before I was twenty years old, I ruined my voice coolin’ chili.” In his vernacular, he compares a lawyer to a bullfrog: “All that ain’t belly is head, and that’s mostly mouth.” A levelheaded East Texas woman is one whose tobacco juice runs evenly down both sides of her mouth. Everybody in his hometown is a Baptist, he says, “unless somebody’s been messin’ with you.”

A few hours before his speech, as he sits down in his Best Western Airport Hotel room to drink some coffee and eat a piece of apple pie, Murphey bows his head for a quick prayer, then gets down to business. As part of his prespeech ritual, he takes a sheet of hotel stationery and writes down a list of the stories he wants to tell that night. The notes, in hieroglyphics that only Murphey can decipher, begin: (1) Gathered for noble purpose. (2) Nice trip (fly or swim) (plane fell on it) (trailer family). (3) Hospitality (carrot juice–vodka). A page and a half later, after he finishes, he folds the paper and sticks it in his coat pocket. He will not look at it again until he returns home to Nacogdoches and places it on top of a wobbly stack of other hotel stationery that constitutes his life’s work. The man has no filing system. He has never written down any of his jokes. Even Nada, who has heard his jokes “so many times I could spit,” says she couldn’t begin to catalog them. When he dies, his tales will go with him.

“Let’s go shoot a little bull,” says Murphey, and he heads out for a large dining room housed in a metal building behind the Ector County Coliseum. Awaiting him are nearly two hundred West Texas accountants and their invited guests, many of them mixing their bookish three-piece-suit look with the garb of the West: boots and belts with big metal buckles. The bespectacled Nigel Cowan, an Englishman who came to Texas thirteen years ago and who is now president of the accounting group, takes one look at Murphey cheerfully shaking hands all around, asking people if they’ve had any rain, and says, “Yes, the man is rather Texan-looking, isn’t he?” Even for people who have lived here all their lives, Murphey embodies the qualities of the professional Texan: He lives on a ranch, raises cattle, owns seventeen pairs of cowboy boots, loves barbecue, keeps a lariat in the trunk of his car and a pistol in the glove compartment, and tells lies better than anyone around, even if he does have to pause occasionally in midsentence to spit out a little tobacco juice.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Murphey begins, in his trademark nasal whine, “we gather tonight for what I consider is man’s most noble purpose . . . and that is to eat supper.” Looking up at the figure peering sternly from behind the podium, his eyebrows furrowed and his head cocked like a rooster’s, the empty left jacket sleeve tucked neatly into his coat pocket, the accountants start chortling. Murphey slides into a few food stories that were not on his hotel-stationery outline (“I don’t like cafeterias. You know why? It’s like getting married. When you go through the cafeteria line, you’re always proud of what you got until you look around and see what the other fella got”).

Then, as the laughter dies down, Murphey hits them with his not-an-expert routine. “Now, ladies and gentlemen, I didn’t come here to talk about professional accounting. I don’t know nothin’ about capital gains or eligible deductions. I don’t know nothin’ about credit and nothin’ about debits.” And here he hits the pause just right, while his face tightens up in a confused manner. “I’m a little bit surprised,” he says, “that I ain’t yet been appointed to some committee to revise the revenue code.”

The accountants bust a gut. Like tumbleweeds in a windstorm, Murphey’s stories head one way and then suddenly go another. He fires off the tale of the ol’ boy who tried to breed his bad coon dog with a parrot so when the old hound got lost, he could ask directions back to the house. Then he segues into the ignorant farmer who was so desperate for culture that he and his wife drove to Kilgore over icy roads one winter night just to see the famous Van Cliburn perform with that great big head of hair. When Cliburn came onstage to announce that because of bad weather the concert had been canceled, the old man stood up and said, “Please, Mr. Cliburn, we’ve driven such a long way. Couldn’t you sing us just one purty little song?”

Although after-dinner speakers are a rarely publicized breed—they don’t get booked on the Tonight show, and they don’t perform before adoring fans at sold-out concerts—in some ways they have a much harder job than their more famous comedian counterparts. In front of small audiences who have been stuffed with mediocre chicken dinners and numbed by endless awards presentations (“Here are this year’s six nominees for the Bronze Winner’s Circle, and let’s hold our applause until all have been introduced, shall we?”), the after-dinner speaker must rise and, in thirty to forty minutes, put a smile on people’s faces before they hurry home to catch the ten o’clock news.

It is a lonely profession. Always on the road—“What’s been like a salt on my wound,” says Nada, “is that Murphey wasn’t home much when our daughters were being raised”—an after-dinner speaker must eat with a group of strangers, make some small talk, give his speech, and head back to his hotel room. Yet the field is loaded: Of the 3,600-member National Speakers Association, about 300 are from Texas, mostly the motivational Zig Ziglar types who like to tell the crowd that with hard work, happiness is just around the corner. Murphey is amused by such speakers—he calls them “motes”—and wonders why they can tell others how to be a success when many of them have not been a success at anything except public speaking. “They get up there with a three-hundred-foot cord,” he says, “and run up and down, jumping around, throwing up charts. Gracious, it’s hard for a man to get in a good hour’s nap during that kind of speech.”

Murphey, of course, is of different stock altogether, a throwback to a colloquial kind of banter that is now just a weak side stream of American humor. His speeches reflect the rollicking, backslapping storytelling that used to dominate the Texas frontier. Out of the love of romance, and no doubt because there was little available reading material, people relied on the tall tale to laugh at their own hardships as well as their own silliness when they struck it rich. It was not the cracker-barrel sage who was prized as much as the man who could come up with some wildly exaggerated story about the lack of rain or the constant wind or the snakes so lethal they could poison a man’s wooden leg. To help get himself elected to Congress, frontiersman Davy Crockett, who would have made a fine after-dinner speaker, told audiences funny stories about how he killed wild bears. Other storytellers made up legends of such mythical Texas heroes as Pecos Bill or oilman Gib Morgan, whose derrick was so high that it took a man fourteen days to climb to the top.

As a boy in Nacogdoches, Murphey would listen to his father, who owned a laundry, swap tales with old friends. He also heard men talk on the bench in front of the local feed store. One man would tell a funny story, which would prompt a story by a second man, leading a third man to recall even another story. On and on it would go, into the late afternoon, with no apparent purpose, stories that a listener would not believe yet not truly disbelieve either, for they wove a verbal tapestry about a people and their place, about little towns where the imprint of civilization was usually no more than the dust kicking up behind someone’s car.

Since the age of eleven, when his left arm had to be amputated after a fall from a horse, Murphey had to rely heavily on his verbal abilities to distinguish himself, because he knew he could no longer become a great athlete or rodeo star. “I found out pretty early I could make people laugh,” he says, “and it was such a wonderful feeling that I didn’t want to lose it. I remember getting up in front of the local Rotarians one day to tell them about the Boy Scout jamboree I had been to, and as I kept talking, they kept laughing. I just stared at them, thinking maybe I could do this for a living.”

After college, he went to law school at the University of Texas. It was while working as an elevator operator at the state capitol to pay his way through school that he began to notice Nada, who worked there as a secretary. “Every time I got on the elevator, that durned boy was talking, and he wouldn’t stop,” she recalls. “It was like he came up with a new story every time he saw me.” On their wedding day, she made Murphey, who always wore cowboy boots, wear a pair of tie-up shoes. He complied, but just before the reception he slipped away to get back into his boots.

Murphey was adamant about trying to do everything a two-armed man could do, even nailing a board between the two handles of a wheelbarrow so he could push it himself. To this day, he regrets not making Eagle Scout because having just one arm made it impossible for him to fulfill his lifesaving requirements. “Losing the arm might have been the best thing to ever happen to me,” he says, “because it made me so determined to achieve, to be somebody. I didn’t want to be just a one-armed boy from Nacogdoches.”

Though Murphey likes to kid himself in his speeches—he says that he is not going bald but clearing ground on his head for a new face—he is too proud to mention his missing arm. He doesn’t want people to feel sorry for him. When asked about it, he does keep his sense of humor, however. A boy came up to him once and inquired how he lost it. Murphey leaned down and said, “I’ll tell you what happened if you promise not to ask me another question about it. Do you promise?”

“Yes, sir, Mr. Murphey.”

“It was bit off.”

Murphey began giving humorous speeches to little groups in 1949, when the state House of Representatives voted him into the position of Sergeant at Arms, where he was in charge of keeping order among the legislators. His talks often concerned his work in government. “When meeting a politician for the first time,” he would say, “keep a close look on his face. Pay particular attention to his mouth. If it’s open, he’s lying.” In 1954 he became Nacogdoches’ district attorney, a post he held for six years. When he resigned, he figured he would spend the rest of his days in private practice, but he kept getting so many requests to speak before little chambers of commerce and rural electric co-ops that in the mid-sixties he made after-dinner speaking his full-time occupation. “He could have been a great lawyer,” says Nada, “but there was something about him that loved telling those old jokes to every hole-in-the-wall organization around. When this guy from Lone Star Steel called and said they’d pay him two hundred and fifty dollars for a talk, ol’ Murphey was floored. His eyes lit up, and I knew that was the end of the law business.”

Today Murphey charges $1,750 a speech, but he has gotten more (as much as $3,500 to speak before a convention) and taken less ($500 to speak in a small town). Although he still keeps a two-room law office in downtown Nacogdoches in the Stone Fort National Bank, he practices little law except to draw up a will on occasion for an old friend. Murphey has no receptionist or answering machine. Unlike other speakers, he has no agent, no brochure describing his speaking ability, and no audiotape to mail to prospective clients. “I ain’t got time for modern marketing,” he says. “If they want me, they’ll find me.”

When he gets a call, he shouts boisterously into the phone, “Yallow! . . . Yassir, this is him speaking to you directly! . . . Why, I’d be honored to come give a few humble words before your organization. Just let me check my schedule.”

It’s a Friday afternoon at the Hyatt Regency in Austin, and Bob Murphey is tired. He has driven in from Winnie, where he spoke the previous night at the chamber of commerce dinner, and now, leaning against a banquet-room wall, he takes a deep breath before addressing the national meeting of relocation experts for the Century 21 real estate company. A couple of hundred men and women in gold Century 21 jackets, most of them from outside of Texas, are told they are about to hear a real Texan talk about Texas.

Slowly, looking a little peaked, Murphey takes off his hat and walks to the microphone. He gets the audience to chuckle when he recalls sitting beside a thin real estate salesman on an airplane. “I leaned over to him and said, ‘Are you on a diet?’ ‘No, sir,’ he said, ‘I’m on a commission.’ ” They politely laugh again when he recalls the two salesmen discussing their day. “One says he made some good contacts. The other says, ‘Yeah, I didn’t sell anything either.’ ”

The speech, however, isn’t gaining momentum. Then Murphey rubs a hand over his bald head. A familiar old gleam comes to his eyes. “Y’know, I can’t stand to be nowhere without my hat. I wear it everywhere. Of course, one summer I got it stolen while giving a speech,” he says, “and I swear I almost froze to death driving home.”

The sudden burst of laughter gets his juices flowing. Murphey launches into a story about the proud Texas father bragging to a Yankee over his fourteen-year-old son’s ranch, a hundred miles wide, with thousands of cattle and a big two-story ranch house with a swimming pool. “Well, now,” says Murphey, “the visitor to Texas looks a little confused and says, ‘How could a fourteen-year-old own all that?’ ‘He earned it,’ the father says. The Yankee looks at him. ‘Earned it?’ ‘Dang right he, earned it. He got four A’s and a B on his report card.’ ”

Bang. The crowd falls apart. Though a rich-Texan joke is a worn-out cliché, the punch line utterly predictable, it is the quintessential Bob Murphey story, the kind his audiences want to hear about Texas to confirm their suspicions that life here can be hilariously out of focus. Murphey plays this humor like an accordion, the notes so exaggerated that it’s hard not to smile. Yet watching him tell these stories over and over, one cannot help but wonder if he doesn’t get bored with it all. How many times can he talk about the country cafe with food so bad that the flies buzz around trying to get out? Or the one about the lazy ol’ boy at the general store who, when asked how long he had been working there, replied, “Ever since the boss said he was going to fire me”?

Murphey, a man well versed in politics and economics, is far from a compulsive class-clown type who always has to act funny. Nor does he fit the standard analysis given of many comedians: that he uses his humor as a cover for some deep pain or insecurity. In Nacogdoches Murphey’s life is strikingly normal, even if he is a celebrity of sorts for his five-minute radio commentaries, done off the top of his head and aired each morning.

Still, while spending a day with him in Nacogdoches—a commonplace town known as the oldest in Texas, one that has uneasily tried to maintain its neighborly, traditional ways despite an influx of rootless new residents and businesses—a visitor can find some clues as to why Bob Murphey would feel a need to spread his old-timey humor on the after-dinner circuit.

Every morning, kissing his wife as he heads out the door, he says, “Honey, I’ll see you regular,” an old-fashioned term that means he’ll see her later. He then drives the six miles from his 350-acre ranch into town to check his mailbox at the post office. Though it would be just as easy to get his mail at home, Murphey could not imagine a life without a daily visit to the post office, where he sees town characters like Bieto Bessler, who hasn’t missed a Rotary Club meeting in fifty years, and where he complains about the delivery of the mail. “The U.S. government was created to do two things—deliver the mail and defend our shores. And that’s what they do the worst,” Murphey growls as he returns empty-handed to his Mercury Marquis, reaching over with his one arm to shut the door that, over the years, has turned brown from failed attempts to spit tobacco juice out the window.

When he drops by the mezzanine of the bank to drink coffee with some of the boys, many of whom he has known since they were all in elementary school, the conversation is about the distance in miles between two East Texas towns. It is the kind of subject that old coots with time on their hands can make last for an entire day. Each man has an opinion. “It’s like the ol’ boy who stopped at the gas station to ask how far it was to Alazan,” Murphey pipes up, referring to a nearby town. “The man says eight to ten miles. The driver says, ‘Eight to ten miles? Is it that far?’ The gas station attendant says, ‘You’ll wish it was farther once you get there and see the place.’ ”

“Heck, I’ve heard his stories since 1933,” says W. L. Boatman, a retired rural mail carrier and a regular member of the coffee group. “He told the same ones back in school. And you know, I don’t know why we still laugh at them, but we all do.”

As Murphey, puttering around in his car, describes the town landmarks, it becomes obvious that Nacogdoches, for him, is a little postage stamp of reality in an inexorably changing world. He slows down as he drives past his alma mater, Stephen F. Austin University (“It’s a cultured place,” he says happily, “with real toe dancers and musicians and all”), and he takes his hand off the steering wheel to point out the fire station where he served as volunteer fire chief. Then he heads over to the hardware store, whose former owner, Mr. Monk, he regularly quotes in his speeches as saying, “It ain’t the cost of living that’s the problem but the cost of living high.” Murphey drops into Milford’s Barber Shop, a lost-in-time kind of place where two shotguns lean up against the wall. The men there swap disparaging remarks about boys with long hair, a subject most people dropped years ago. “Oh, no,” says Murphey, dead serious. “You can still see some of these college boys around with Daddy’s money and Mama’s hair.”

There is a strong nostalgic pull to this kind of small-town life, which no doubt has helped bring many newcomers to Nacogdoches. But instead of going to the creaky old Shaw’s department store in the town square, they’d rather zip out to Wal-Mart. Instead of eating at one of the venerable barbecue joints, they find it easier to drop by a fast-food restaurant. “This ain’t going to ever come back,” says Bob Murphey, looking at the town square. ”I suppose it’s just a little too much behind the times.”

Perhaps, too, that is why Murphey holds such an appeal when he speaks. He is comically—and gloriously—out of date. In his garage is a 1925 Model T Ford and a big 1953 Ford that he gave his wife for their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary. Every time he puts on a tie, he wears the same tie tack that he bought in 1938. And though it is true that his speeches are not consumed with great modern ideas or grand gestures, his humor has never been plagued by the miseries of urban life either. Considering the way audiences roar back at his timeworn jokes, it becomes obvious that what they really like about Bob Murphey is the chance he gives them to hark back to a less complicated way of life, where, as he says, “people had a chance to sit on the front porch and talk. Heck, people in the cities don’t even put front porches on their homes anymore.”

“Like the country woman who said she didn’t enjoy spreading gossip but didn’t know what else to do with it, Bob Murphey has passed along his earthy philosophy and clean humor to neighbors from coast to coast,” says the emcee of the Law Enforcement–Traffic Engineering Highway Safety Seminar, finishing his introduction in the Hall of Fame Room at the Sheraton Centrepark Hotel in Arlington.

Tonight the audience is in Murphey’s hands from the very start. They are mostly country people or one generation removed from the country: big highway department fellows whose ties come down to their navels and whose wives’ hairdos are so heavily sprayed that they could stop a flying hockey puck.

“Have you noticed I ain’t told no jokes on the women tonight?” Murphey asks in an earnest voice. “I don’t do this. A lot of my contemporaries do, but I don’t.”

He pauses, his hand sternly holding the lapel of his jacket, and one can feel the setup coming. “Although I do not tell them, I’m surprised at all the people who come up to tell me jokes on women. It’s disgusting. It embarrasses me when I hear them.”

There’s another, longer pause. Murphey’s face is expressionless.

“I heard one just the other day.”

It’s like a bomb goes off. Both men and women throw their heads back, laughing. Murphey, apparently regretful, tells them about the three-year-old boy greeting his father as he drives in from work. “Ol’ Daddy noticed his boy was crying and said, ‘What’s the matter with Daddy’s little man?’ The little boy, big tears coming out of his eyes, said, ‘Mother ran over my tricycle with her car.’ Daddy said, ‘Son, I’ve told you a thousand times. Don’t leave your tricycle on the porch.’ ”

It might be easy to dismiss the folksy, slightly redneck Murphey as just a funny little man with a practiced country-boy shtick. But through a bottomless repertoire of provincial, antiquated stories, he has found a way to define himself. For him, the way a tale is told has as much value as the truth it holds. Now, as he wraps up another speech, he gives the Arlington group some remarkably commonplace pieces of advice—do the best you can, nothing substitutes for hard work, never forget to laugh—and then, with the audience readying itself for his big summation, he offers his final words.

“Let me close with this, and I’ve said this across the width and breadth of this nation, in forty-four states, before every kind of group you can imagine, and not once have I been contradicted. I hope you go home with this foremost on your mind. Ladies and gentlemen, the richest man in the world”—and here Bob Murphey makes one of his long, dramatic pauses, the kind of pause that signals an upcoming moment of great meaning—“is the man who has the most money. Thank you very much.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Nacogdoches