This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The first Alamo movie was filmed within living memory of the siege of March 6, 1836, and only a couple of miles away, at Hot Wells Hotel just outside San Antonio. Gaston Méliès, the head honcho of the Star Film Ranch, filled The Immortal Alamo with all the pomp and spectacle that a 1911 one-reeler could contain. With a running time of about ten minutes, The Immortal Alamo gave audiences the fall of the Alamo, the Battle of San Jacinto, and a romantic subplot to boot. This admirable sense of brevity did not catch on with subsequent Alamo moviemakers, but the basic ingredients of the film did: romance, action, tragedy, patriotism.

The Immortal Alamo didn’t make much of a splash in its hometown—its premiere wasn’t even covered in the San Antonio newspapers—but the floodgates had been opened. No generation since 1911 has been without an Alamo movie of some sort; there have been sixteen, all told. The latest, the spectacular Alamo . . . The Price of Freedom, is now in its fourth year at San Antonio’s IMAX Theatre Rivercenter.

The Price of Freedom, a docudrama, is considerably more careful with the facts than other Alamo movies have been. The rest all talk a good game— trumpeting the extensive research and rigorous attention to detail that went into the productions—but when push comes to shove, each Alamo movie is less a reflection of the reality of 1836 than an exciting and romantic meditation on what each generation wants to think about those events. Historians shake their heads in disgust, but movie fans don’t seem to care.

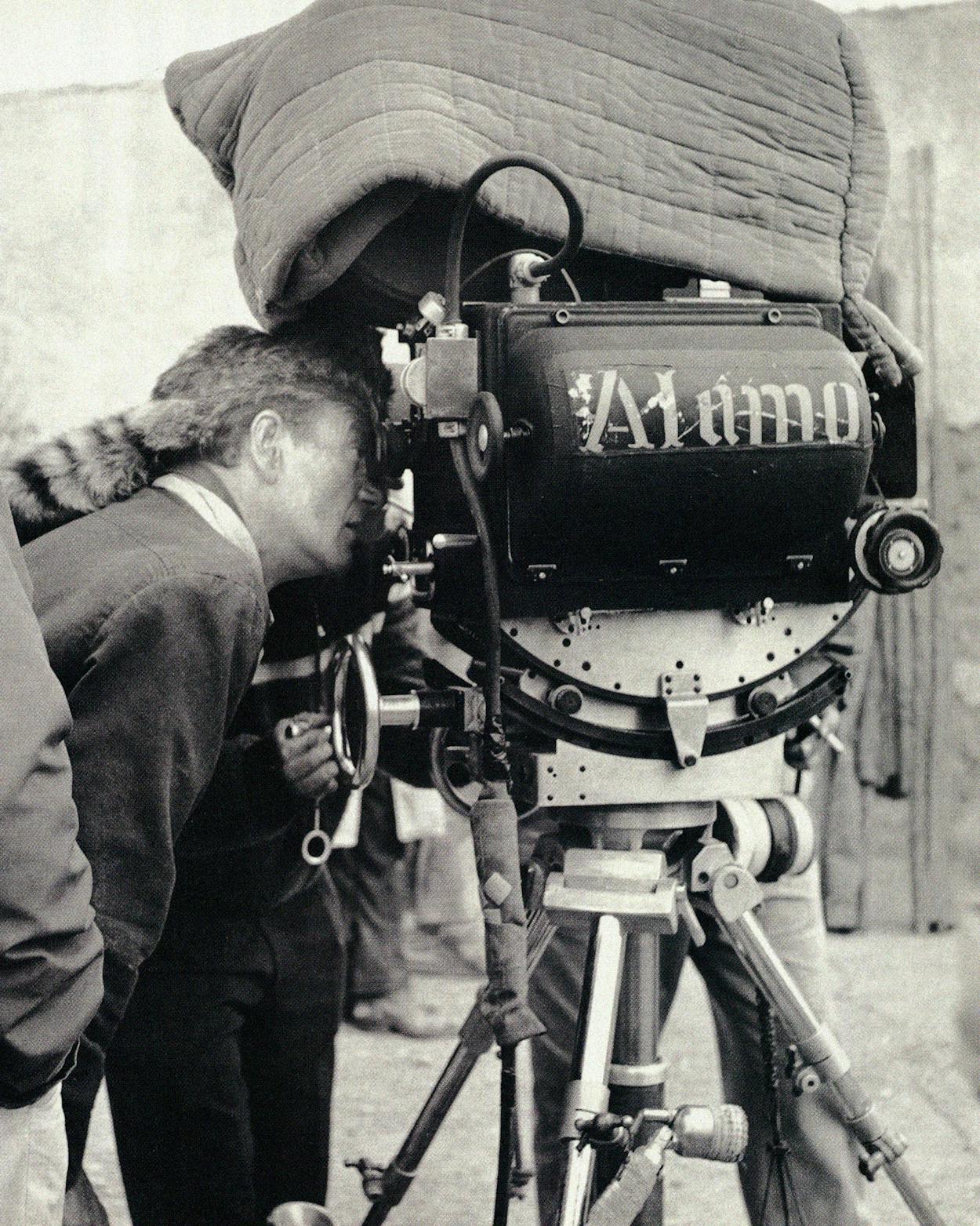

Certainly John Wayne’s Alamo (1960)—the great kahuna of Alamo movies—has virtually no connection with the facts. A huge, obsessive, extra-crammed budget-buster, The Alamo is threatened by a tedious script that is interrupted now and then by stimulating bursts of action and cumbersome attempts at comedy. But it’s a better movie than its reputation suggests; it has on its side Wayne’s compelling personal vision—he produced, directed, and starred in the film—and the visceral impact of Todd-AO, a gigantic 70mm film process.

At least it did in 1960. Since then, most fans have experienced The Alamo only on the cramped confines of a television screen, which is a bit like knowing the Grand Canyon only through Viewmaster slides. Worse, The Alamo was cut by 31 minutes soon after release in an attempt to bolster box-office sales. That footage was never seen again, even though its loss renders many of the film’s plot points incomprehensible. To those who think The Alamo is too long-winded now, the prospect of an additional half hour might seem terrifying, but restored to its original form and length, The Alamo would make more sense and possibly gain a tad more respect.

In the wake of the successful restorations of Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Spartacus (1960), the time seems ripe to put The Alamo back together again. There’s even a recently discovered uncut Todd-AO print to work from. But there isn’t much interest by MGM/Pathe, the company that owns the film at the moment. Robert A. Harris, the restorer of Lawrence and Spartacus, wants to work his wonders on The Alamo, but the money—an estimated $200,000 to $400,000—isn’t forthcoming.

Instead, MGM/Pathe plans a kind of stopgap measure. This summer it is going to copy the cut scenes from the 70mm print and interpolate them into a regular 35mm print for limited release.

That may be okay for those who like their legends cut down to size. But for all The Alamo’s faults, wouldn’t any good Texan give his eyeteeth to see the most legendary of Alamo movies back in 70mm and with six-track stereo sound and bigger than all outdoors? What this movie needs is a sugar daddy to fork over some of the long green to give The Alamo what the Alamo never got: a happy ending.

Frank Thompson, a writer and film historian, is the author of Alamo Movies (Old Mill Books).

- More About:

- Film & TV

- TM Classics

- Film

- San Antonio