This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Bemoaning the loss of a favorite possession, Dagoberto Gilb sounds like a character in one of his short stories. “They took my ’62 Chevy, man! The city did. I’m keeping it all shined up, thinking my son would like to have it. But Antonio is sixteen, he don’t want nothing to do with the old man’s Chevy.” Standing on the front porch of his quarry stone house on a corner lot in El Paso, the 45-year-old writer nods at the curb and street. “If I park it out there, it’s gonna get creamed in all the traffic. We don’t have a driveway, and parking on the side street is restricted, ’cause it’s a school zone. So I put my car up just over the curb beside the house, to protect it. The city passes a law that says, No cars in the yard. Unsightly appearance, bad for the neighborhood. And we got this old lady who drives around looking for violations. She turns me in, and the city tows it off. A ’62 Chevy? That is the neighborhood!”

Gilb once wrote a story, “Parking Places,” about the absurd tensions born of urban constriction. And this particular misadventure is emblematic enough of the shortcomings of life in his adopted hometown—at least in Gilb’s mind—that he weaved an abbreviated version of it into a recent essay. But, Dagoberto, a visitor suggests, times are good now. “You’ve got the money. If the city impounded your car, pay the bill, get it back, and find a place to store it. “Yeah, well,” he mutters. “It’s kind of hard to get it started right now.”

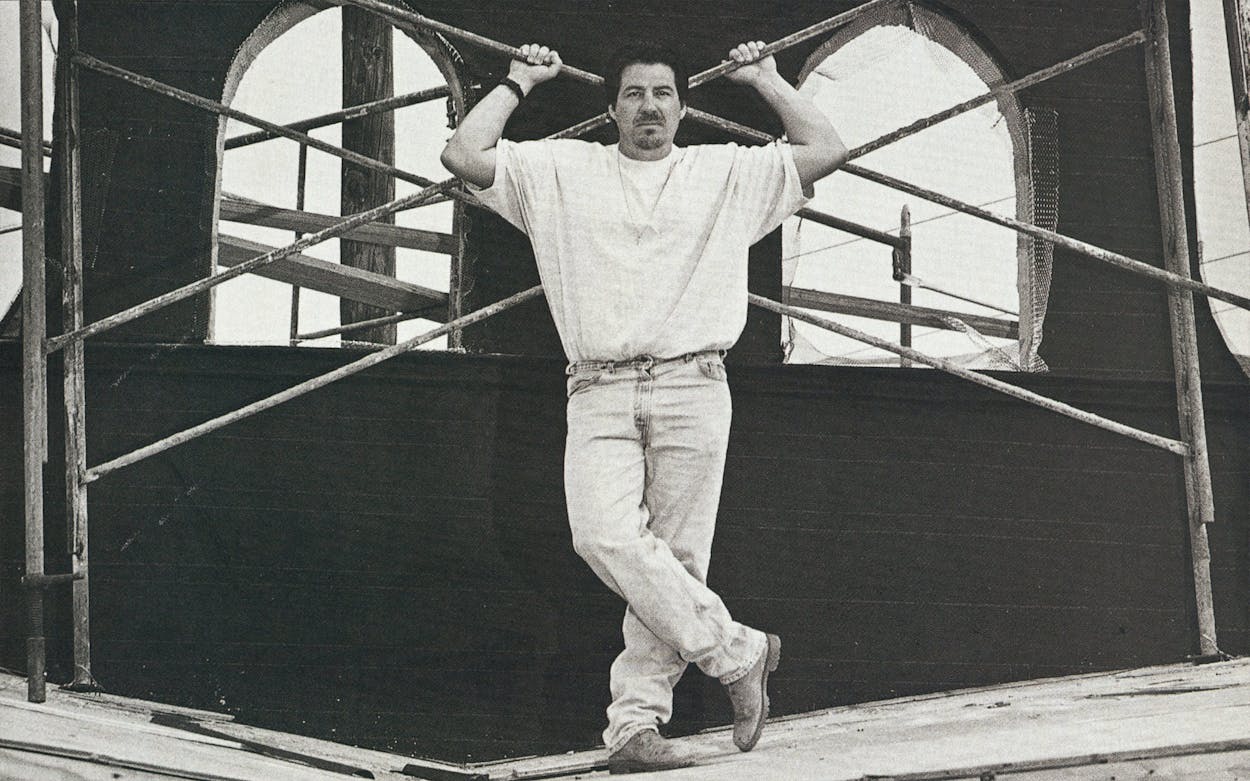

Gilb’s short stories are distinguished by a mix of gritty humor, mundane terror, and economic misfortune. They are set vividly in cities of the desert Southwest and usually feature a Hispanic protagonist who is good-hearted but often irresponsible and is forever one pink slip or automotive breakdown away from disaster. Published since the early eighties in literary quarterlies that might pay him $100 a story, Gilb financed his writing and kept his family afloat by working in construction—first as an unskilled laborer, then as a union carpenter. In 1993 he found himself involved in a career turnaround that still has his head spinning.

Shunned by the publishing coterie in New York—George Plimpton told him his writing was “too colloquial”—Gilb sold a story collection, The Magic of the Blood, to the University of New Mexico Press. The book won the 1994 Texas Institute of Letters’ annual award for best fiction; the same year in New York, it was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award, a book-of-the-year prize judged by heavyweight writers; and it won PEN’s Ernest Hemingway Foundation Award for the American debut of the year. Gilb went on to receive prestigious Whiting and Guggenheim fellowships. Topping off this abrupt and drastic change of fortune, last year wunderkind editor Morgan Entrekin, who is reviving Grove Press, brought out Gilb’s first novel, The Last Known Residence of Mickey Acuña. All at once, Gilb was making a living as a writer, and the literary establishment he had railed against was fawning all over him.

On his front porch in El Paso, he recalls a time, far too close for comfort, when his family was in dire peril of eviction. Against that he poses a recent call from a man with public radio in Germany. The man said he wanted to interview Gilb and then go straight on to a session with Nobel laureate Saul Bellow. “Oh, yeah,” Gilb says, laughing. “Me and Saul. Always thought of us together.”

Gilb is a product of the Los Angeles melting pot. His mother had immigrated illegally from Mexico City as a child; his father, a man of German ancestry, supervised a laundry in central L.A. As a reformed street tough, Gilb got a degree from the University of California at Santa Barbara, majoring in philosophy and religious studies. Trying to write a novel, he got into construction when he found out he could make $50 a day. “I’d lie,” he says. “I’d say, ‘Sure, I’m a carpenter. I know how to make rock walls.’ The foreman would come around and watch, then say, ‘Man, get out of here.’ But I’d get two hours in. I might get a week. And I’m not stupid. I was learning. The next time I lied, it was closer to the truth.”

In 1976 Gilb put down roots in El Paso. “My mother always talked about El Paso,” he says. “It’s like the Ellis Island of Chicanos.” He thought the city’s spare and arid look was beautiful, and he liked the isolation. He was encouraged in his writing by the late short-story master Raymond Carver, a guest writer one year at the University of Texas at El Paso. But Gilb spurned Carver’s offer to put him in the chummy loop of the university creative writing crowd. However pure, his life as described in stories such as “Where the Sun Don’t Shine” was as hard as nails. A smart-aleck, macho worker is fired and humiliated by a redneck foreman. After a night of booze and brawling, the man has to tell his wife that he’s jobless again and they no longer have medical insurance. “We had an argument,” the story’s protagonist explains. “You can go and apologize,” his wife counters. “I already hit him,” he lies, salvaging a pathetic dignity.

Gilb won a coveted Dobie-Paisano fellowship in 1987. Following a productive six-month stay at J. Frank Dobie’s old ranch west of Austin, where he began his novel The Last Known Residence of Mickey Acuña, he was offered a one-semester appointment at the University of Texas at Austin as a visiting writer. “You have to accept,” quipped his wife, Rebeca, a high school teacher in El Paso. “Or nobody will believe they offered it.” Gilb admits he misbehaved. Among other things, he put a sign on his office door that read, “Professor Gilb is not feeling very professorial today.” A colleague kicked him out of her office for suggesting that a brief job as a custodian in Palo Alto, California, didn’t exactly qualify Raymond Carver as a champion of the working man. Back in El Paso, he gave up on New York publishing and sold his story collection to the University of New Mexico Press. He was at a point of crisis: He didn’t think he could support his family with his writing, but he could feel in his bones that he couldn’t go on in construction. “What’s the new great industry in Texas?” he asks. “Prisons. I applied for a job driving a prison bus. I couldn’t even get hired doing that.”

Then the book of stories took off, and amid all the prizes and praise, Entrekin accepted Gilb’s novel. The novel has the strengths of Gilb’s short fiction: hard-edged, poetic dialogue that jumps in mid-sentence between English and Spanish, and a deep understanding of a Texas city that has more in common with Tucson and Los Angeles than with Houston and Dallas. But Mickey Acuña and his gang of misfits are so immobilized by their pasts that they seldom venture outside the El Paso YMCA—workable material in a short story, but it makes for an extremely uneventful novel. (Gilb indicates that his next novel, 20 lbs., about a troubled marijuana shipment from Mexico to Colorado, will be livelier and funnier.) Grove, which he associates with the outlawry of Henry Miller, is the publishing house of his dreams. But wouldn’t you know it? The Grove reprint of his story collection plays up a blurb from The Nation on the cover: “Gilb’s fiction is the most exciting and emotionally draining since Raymond Carver’s.”

Has the angry young man been co-opted by the elite he used to love to hate? Not really. Like his characters, Gilb pops off without malice. “Cormac McCarthy,” he says of another celebrated El Paso writer, “wouldn’t give me the time of day. He doesn’t hang out with anybody but rich people.” But in the bluster, Gilb doesn’t spare himself. “I was at this big arts event in Washington, and I made a fool of myself,” he says watching his son Ricardo pitch for a Little League baseball team called the Padres. “Later I get this call: ‘Al Gore was really impressed with you.’ ” Gilb guffaws, then points at the pitcher’s mound, where his son is struggling. “You know what Gore and I talked about? That baseball team. Hey, Ricardo!” his big voice booms. “Throw it hard. Just hit the glove.”

- More About:

- Books

- Writer

- TM Classics

- El Paso