It was just past two o’clock on an early spring day in 2004 when the Cameron County Sheriff’s Department received a call from a desperate woman. Her brother-in-law was holding her sister hostage inside their home in Olmito, a normally serene community of 1,200 souls just outside Brownsville, a few miles from the Rio Grande. Sheriff’s deputies sped to the scene, a languid road dotted with simple homes and ranches with Spanish names like Palo Blanco and Las Campanas. The husband jumped into a Dodge pickup and fled, the red and white and blue lights of the deputies flashing behind him. When he realized escape was impossible, he reversed direction, skidded into his driveway, and vanished inside the house. One deputy kicked in a door but ducked into a bedroom when he saw the man reach for a shotgun. Other deputies entered the house, and one of them fired at least two shots at the suspect, missing. A struggle broke out. There was blood on the tile floor, shattered glass, the smell of pepper spray. When the man, 65-year-old Rodolfo Federico Garza, was finally in handcuffs, he argued with the deputies that they were not supposed to be there. He had a personal arrangement with the sheriff.

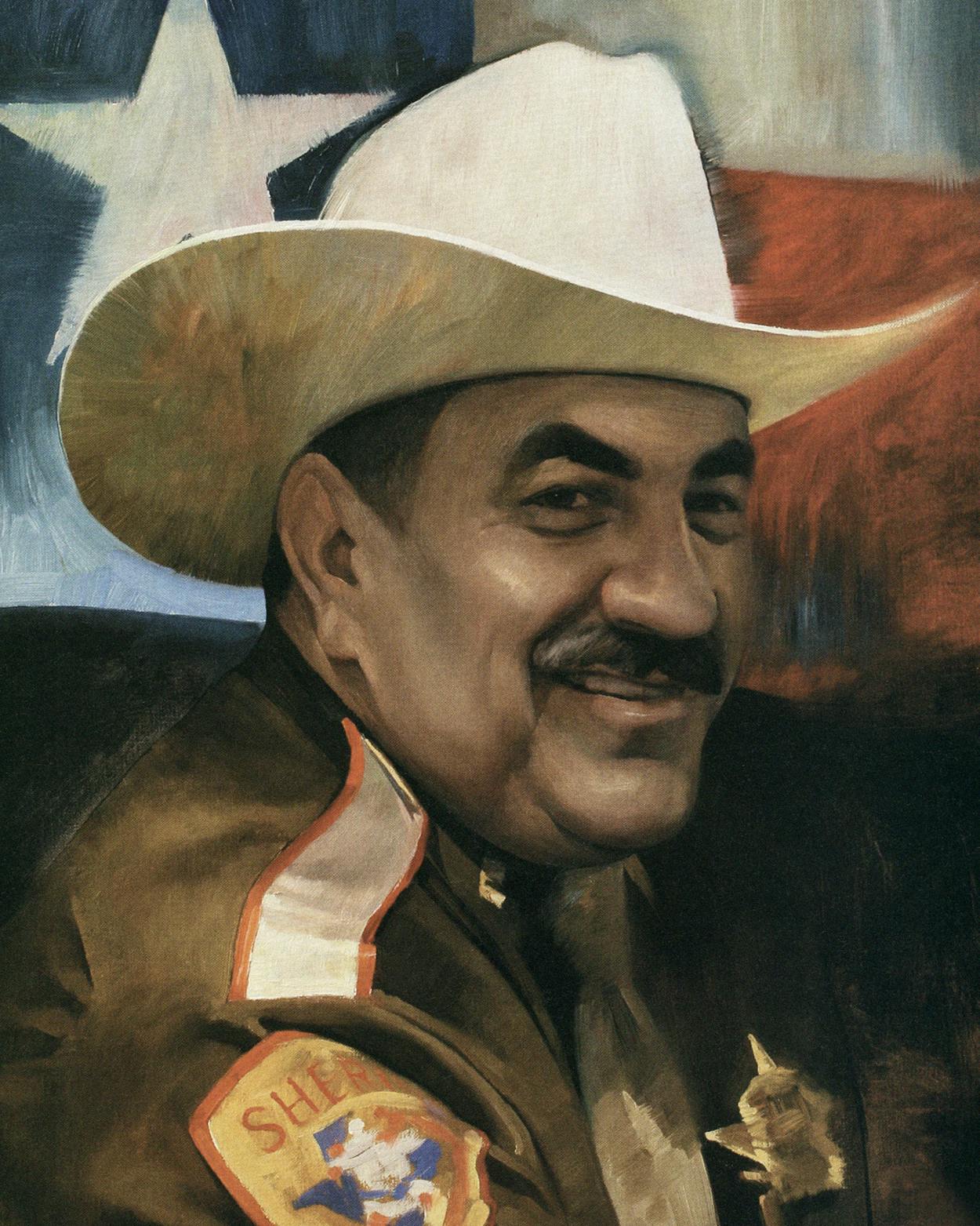

Sheriff Conrado Cantu, the top-ranking law enforcement officer in the county, lived just down that farm road in a low-slung, brown-roofed brick home. He was well known and well liked in the area, as he was throughout the South Texas county. In the dual world of the border, Cantu was American by birth but seemed more at ease speaking the region’s predominant Spanish language. Now, the hostage incident—which would have been erased from history if his will had prevailed—hinted at another person behind the star he bore proudly on his chest.

A captain arrived at the scene of the dispute. Rumaldo Rodriguez, who was considered one of the sheriff’s most trusted aides, pulled aside a deputy and warned him that what he was about to say was “off the record.” His orders were terse and nonnegotiable. The sheriff’s department needed to make everything disappear, Rodriguez said. No reports should be made. The media should not find out. He approached another deputy, who was already being questioned by a sheriff’s department investigator, and ordered him to end the interview and leave. Rodriguez told a third officer that Rodolfo Garza would be taken directly to the sheriff.

The captain questioned Garza, who admitted that he had pointed a shotgun, that shots had been fired, and that he had known he was evading arrest when he drove off in his pickup. Rodriguez ordered that the man be uncuffed. He let him go back inside his house and change his clothes. Then he personally drove Garza to the sheriff’s home and released him. The matter would have ended there had someone not tipped off the district attorney, a practice that concerned county residents and employees had used for years as the only way to hold the sheriff accountable for his actions. But Garza would never go to jail.

The official who had orchestrated Garza’s release on his cell phone was a different Conrado Cantu from the one most of his constituents thought they knew. Not until the feds whisked him away in the summer of 2005 was the picture of this other man complete, and even then his former supporters wondered exactly how he had come to such a bad end. Perhaps he wanted to please everyone. Or he was not that smart. Or he was somebody for whom everything seemed easy. Or he was somebody—federal prosecutors would argue before a judge—whose concept of the law was deeply flawed and damaging to the administration of justice in Cameron County. Indeed, after the district attorney had scrutinized his every move and the FBI had retraced all of his missteps, Cantu came to stand for the worst of South Texas politics and law enforcement: the idea that the law serves the lawman, not the other way around. Even worse is that local políticos and constituents let him get away with it for so long.

Conrado Cantu had been in law enforcement for only five years when he declared himself “the people’s candidate for sheriff” in January 2000. “The new times are crying out for a new generation of leadership,” he discoursed in a local newspaper story. Only 44—young by county standards—he worked the electorate with all his God-given charm. He had broad shoulders, a robust stomach, and an intense gaze underlined by a bristly mustache that many women considered handsome. He dressed in elegant cowboy-cut jackets and a Western hat and boots; he played the guitar and was prone to deliver rousing ranchera songs with the passion of a mariachi star.

Cantu was a former plumber, a used-car salesman, and an owner of a seafood restaurant who had served as a chief deputy constable for a year before being elected constable, in 1996. Constables like to think of themselves as the peace officer closest to the people, and Cantu campaigned as “the people’s sheriff.” “You can have all the education in the world. You can have all the experience,” he told a local journalist, “but if you do not work with the people and help them with their problems, you will never make a difference.” He called himself Animo—Spanish for “cheer,” or “enthusiasm.” To be sheriff, Animo preached, one also needed “a tremendous amount of good common sense.”

From where Gilberto Hinojosa sat at the pinnacle of county government, Cantu’s electoral filing made no sense. It was widely understood within the Cameron County Democratic establishment, which dominated local elections, that one had to pay his dues before seeking such a high-profile public office. Not to mention that Hinojosa, the county judge and, some would say, the anointer of local Democratic candidates, was happy with then-sheriff Omar Lucio. During a conversation in Hinojosa’s office in the county’s squat administration building in Brownsville, the county judge tried to persuade Cantu to wait until he had more experience. But the constable couldn’t be dissuaded. He had garnered many fans during his years in office, especially in the county’s poorer communities. His main job was to serve warrants and subpoenas and to assist at justice of the peace courts. Yet he and two other constables found time to launch crime-watch programs and patrol the most remote corners of the county, which the understaffed sheriff’s department had neglected for years. Cameron County stretches over 1,276 square miles and shares its southern border with Mexico. Much of it is rural. Farm implements sometimes disappeared across the river. Nobody asked how the constables were able to recover them without having any legal jurisdiction in Mexico. Residents simply appreciated that crime was down, and parents thanked the officers for talking to their children about staying in school and off of drugs.

The darker truth about the man who had emerged into the political spotlight from nowhere was that he was already under scrutiny by district attorney Yolanda de Leon. According to confidential phone calls to her office, Constable Cantu had rendered prosecution of some criminals impossible by not returning their case files to the DA. He had once let a young man free at his father’s urging after arresting him, and he had used his official position to threaten another man to make good on a bad check he had written to a local business. He had also managed to evade his own arrest on a hot-check charge when the fellow constable who was supposed to arrest him gave him the chance to fix the problem outside the courts.

Perhaps these stories weren’t widely known. Or perhaps his supporters were so loyal that they didn’t care. Cantu defeated Omar Lucio, the incumbent sheriff, in a Democratic primary runoff and went on to outpoll his Republican challenger by 2,341 votes. The Brownsville Herald described him as “the political newcomer who took the Cameron County political scene by storm.” Animo was elated with his new charge, and he promised the supporters who gathered at his campaign headquarters that they would not regret their choice. “I’ll never let you down,” he vowed. Those words would come back to haunt Cameron County.

Politics in Texas’ southernmost county, like politics anywhere, is shaped as much by the past as by the present. For many decades, South Texas political bosses exploited the lever system, by which the poor, uneducated, mostly Mexican American masses could be manipulated into voting for just one political party. The Spanish word for “lever,” palanca, continues to be a useful term today to encourage straight-ticket voting; to a large degree, “palanca politics” is alive and well, with Democrats grabbing virtually all the races for public office regardless of the merits of their Republican opponents.

In Cameron County (population: 378,000), only between 20,000 and 30,000 people vote in the Democratic primary; the number climbs in general elections when the presidential race is on the ballot. Because family is paramount here, one way to begin getting the 12,000 to 15,000 votes needed to win office is to make friends with large extended families, which are not hard to find. The smaller towns in the Valley are also notoriously loyal to their crests, so if a prominent family in a town supports a certain candidate, chances are good that other voters there will do the same. Candidates also boost their support by teaming up with popular candidates in other places, even if the relationships are temporary or contrived. And if more votes are needed, there’s always the option of hiring politiqueras, fierce women political workers who will journey door-to-door to help the eldest of the electorate fill out their early-voting ballots and drive vans crammed with people to the polls on Election Day.

Of course, these kinds of liaisons are not for nothing. After the elections come the laundry lists of expectations and favors owed. “You were going to build us a community center.” “You said you would pave my road.” “You promised my brother a job with the county.” “I voted for you, so can’t you be easy on my friend who was arrested for hitting his wife? He’s a good man.” Promises delivered reinforce constituencies; promises unkept feed a sense of futility among would-be voters and a growing feeling that all políticos are the same. This messy web of relationships is what constitutes politics in Cameron County, and wrapped in that is the everyday necessity of governing, and of governing well.

At the same time that Conrado Cantu was running for constable in 1996, Yolanda de Leon was campaigning for district attorney. But she knew she was getting it all wrong. She wasn’t smiling enough, wasn’t saying enough of the right things, wasn’t shaking enough hands, wasn’t attending enough pachangas or church services or funerals of people she didn’t know. Crowds were not her forte. Fifty years old, she was, by nature, a deeply guarded and reserved person. This didn’t mean that she was unkind, only that she could come off as cold or aloof—not the sort of person who usually runs for office in South Texas. And certainly not like Cantu, who campaigned as naturally as babies learn to crawl.

It was Cantu who first suggested that de Leon try a little harder to engage with voters. Actually, he suggested it to de Leon’s husband, because in the South Texas political world, it is always easier to speak man-to-man. Like Cantu, de Leon was a political outsider who was trying to unseat a well-established politician, but they had little else in common. A matronly woman with short, gray hair, green eyes, strikingly light skin, and a misplaced Southern drawl that she had picked up in Tennessee while her husband was attending dental school, she was as reticent as Cantu was outgoing. De Leon didn’t think he seemed particularly intelligent, nor did she trust the fact that he talked so much. But she had to hand it to him for being able to sense what people wanted to hear and deliver it, the way a talented lover can give a woman a rose and make her feel graceful and beautiful.

De Leon was aware of the political culture of South Texas when she ultimately won her race. But what the new DA was willing to do about it—when, inevitably, she was asked to bend the rules a little or when she discovered someone else was bending them—was another question. A self-described righteous person, de Leon had a laserlike focus on what she thought was just and fair: the ideal of creating a system by which all citizens, rich or poor, could receive the same access to justice. The office she inherited did not measure up to her standards. The previous DA had admitted publicly to having an affair with his secretary. One of his investigators had been convicted of dismissing DUIs. De Leon felt she had a mandate to begin from scratch and take the office in a different direction.

She established strict standards—perceived by some as too rigid—that required her prosecutors to justify the dismissal of any case. In Texas, a district attorney has complete discretion to decide whether to prosecute a case, and her constituents anticipated that she was someone they might massage for help, which they were used to doing. But de Leon’s response when lawyers visited her to request leniency for their clients was always the same: “Let me look at the file. Let me talk to the prosecutor who’s handling the case.” When she turned down ordinary citizens in their requests for favors, which happened all too often, their response was barely veiled: “I voted for you,” they would say, or they might remind her that elections were coming up.

During de Leon’s first year in office, a county commissioner noticed that she was losing some of her battles. “The problem is you don’t know how to play the game,” he told her. “Yes, I do know how to play the game,” she replied. “The problem is, I don’t choose to play.”

By the time Cantu set his sights on becoming sheriff in 2000, de Leon had been DA for four years. She had heard rumors that Cantu offered protection to lawbreakers who would support him for sheriff. She had heard rumors that he might even have liaisons with drug traffickers. Around de Leon’s office, assistant DAs began to refer to the constable as Conrado “Protect the Load” Cantu.

De Leon had called the Texas Rangers and asked them to investigate the accusations that Cantu, who by now had won the Democratic nomination and was certain to become sheriff, was letting lawbreakers avoid arrest by not turning in their case files. While the Rangers were still investigating, however, she recused herself and asked a local judge to appoint a special prosecutor. Her request was granted. But the prosecutor, El Paso district attorney Jaime Esparza, said that while Cantu had no legal authority to dismiss cases simply by sitting on the files, the Rangers’ investigation did not yield enough evidence to prosecute. It might have been de Leon’s biggest mistake as DA to turn over the case; had she won a conviction, she might have prevented Cantu from ever taking office.

If Cantu knew that de Leon had him under scrutiny, he certainly didn’t change his behavior after he became sheriff. One day, he came looking for the DA with a solemn face. He wanted to put in a good word for a man who was facing prosecution. “He’s a good man,” Cantu assured her. It was that same subtle request; again, de Leon replied as she had with others. But unlike the others, who with time learned not to ask for these favors, Cantu had more gall. After he made his plea, he placed a $100 personal check on her desk. “This might help you out,” he said. De Leon replied coolly, “You may want to take that back. You don’t know what I’m going to do on this case.” Cantu tried to backtrack. “No, no, no,” he said. “It’s a campaign contribution.”

For all his supposed political savvy, Cantu had underestimated de Leon badly. She didn’t always react visibly, but her encounters with him and other courthouse politicians who didn’t have the same righteous streak that she did only strengthened her backbone and made her more determined to push forward against public corruption. She was sure that Cantu had flouted the law even before he had become sheriff. She worried what might happen with him at the head of that powerful office. So far, nothing flagrant had occurred, but she had formed an opinion of him that would become reinforced throughout the next four years. “Conrado Cantu didn’t have anything that centered him, that grounded him about law enforcement,” she said much later. “It was all about personal promotion.”

Not for a moment was Cantu’s four-year term as sheriff without controversy. The missing files flap, which had come up during the campaign, never went away. His new management team consisted of two former constables, Captain Robert Lopez and chief deputy Juan Mendoza, who had worked with him during the times of fervid patrols and had resigned from their offices to become his right-hand men. Soon there were published reports indicating that Cantu had hired Mendoza’s father and son and that he was awarding wrecker-service contracts on a preferential basis. His management of the county jail system was questioned after a body was discovered in a jail cell and the county pathologist delivered a preliminary autopsy report that suggested that the inmate might have been murdered, based on “extremity bruising and neck trauma” suggesting “a choke hold at the time he died.” The pathologist later changed his mind and attributed the death to liver failure. A grand jury did not indict anyone. But a subsequent investigation found that no lieutenants were supervising the county’s four jails at night, despite a county policy mandating that they do so.

The first hard evidence of corruption came when a reporter for the Herald revealed that county commissioner Natividad “Tivie” Valencia had written an angry letter to a newly appointed constable whom Valencia had voted to hire. According to the Herald, Valencia questioned why the constable hadn’t given a job to one of his friends. Cantu, Lopez, and Mendoza had promised him that that would happen if Valencia voted for the constable, he told the Herald. Valencia was convicted of bribery, but no charges were brought against Cantu or his top aides.

Cantu had every reason to feel secure. He had continued to expand patrols and crime-watch programs. School principals raved about his appearances. In June 2002 county judge Gilberto Hinojosa issued a press release in which he lauded the sheriff, having become his close supporter. The pair had filmed campaign commercials for Hinojosa’s reelection bid. “Conrado Cantu will be considered a great sheriff,” Hinojosa said, “not only in our county, but across the State of Texas, because he treats every person the same way: with kindness, courtesy and the respect and dignity that they deserve.”

But soon the stories turned ominous. The Herald questioned Cantu’s awarding of the jail commissary contract, worth $1 million annually, to a one-month-old business called A&J Retailers without asking for bids (which was legal under state law). Future articles would detail that the person behind A&J Retailers was Geronimo “Jerry” Garcia, with whom Cantu had had prior business dealings—and would have more in the future. Then, in September 2002, Juan Mendoza III, the son of Cantu’s chief deputy, resigned from his position as a jailer after officers learned that inmates were missing funds from their accounts. The county auditor later reported that the shortage was at least $20,000. De Leon launched an investigation, which led to the young Mendoza’s conviction for stealing an inmate’s gold chain to pay off a truck loan. That fall, several jailers were charged with smuggling marijuana to prisoners.

A more salacious side of the department’s jail administration was uncovered by a TV reporter for Channel 4, the local CBS affiliate, who reported that male jail officers were asking female inmates to have sex with them in exchange for easier lives behind bars. The reporter wrote an inmate who had since been transferred to a state prison in Beaumont requesting proof. The woman sent a three-page handwritten letter that cited times and places concerning her sexual encounters with Lieutenant Joel Zamora, who was in charge of the county’s jails.

It was the beginning of Cantu’s unraveling as sheriff. The day after the story aired, in December 2002, a jail lieutenant named Hilda Treviño received a curt termination letter signed by several of Cantu’s top officers. Treviño had once supervised the female inmates at one of the county’s jails. But after learning that a male officer was taking women from their cells for “private sessions,” as Treviño called them, she posted warning signs that women prisoners were not to be left alone with any male official unless they were supervised by a female guard. When she approached Lopez, Zamora, and Mendoza, they accused her of siding with the inmates over the officers.

Cantu called a press conference the day after Treviño was terminated and insisted that no jail employee had been fired for blowing the lid off the county’s dirty business. “We all know that sensationalism sells,” his statement read, “but it should be backed up with facts that can be verified.” A week later, the Herald reported that de Leon’s office was investigating Zamora and that he had been suspended without pay. (He was later convicted of sexual misconduct.) Within days, the U.S. Marshals Service yanked its female inmates from the county’s jails. The DA and the Brownsville police were now probing the sheriff’s department. If it was still possible to see Cantu as just a lousy administrator rather than a hard-edged criminal, that impression would not last long.

In the midst of all this drama, Cantu told a woman named Sandra Guajardo that he needed a hug. She too had admitted to performing sexual favors for Zamora while clerking temporarily for him. Now she was looking to get rehired, and she called the sheriff to see what he could do. Just after the New Year, Cantu, who considered himself a family man and was married to a local teacher, called her back and asked if he could bring some beers to her house.

The two sat on her couch and talked. According to Guajardo’s telling, after she acquiesced to his hugs, he caressed her and kissed her cheek. He unzipped his pants and pulled them to his knees, pushing her head down. After the deed was done, Cantu told her that he couldn’t promise anything but that he would try his best to find her a job. And when he tried his best, he said, he usually got what he tried for.

Several weeks had passed when the sheriff’s cell phone rang.

“Hello?” a woman said.

“Bueno,” the sheriff replied.

“Hello?” It was Guajardo.

“Animo.”

“Hey, Animo, what are you doing?”

“Yes, you called me?” he said.

“Yeah. Hey . . .”

“It’s because yesterday I was with the family when you called.”

“Uh-huh. Hey . . .”

“Yeah . . .”

“Um, why haven’t you called me anymore?”

“Man, I’ve been really busy with work.”

“You made me feel kind of bad.”

“Why?”

“Well, you know, I mean, after what I did here and everything, you know. After what happened . . .”

Guajardo wanted her payback. The conversation ensued like a nervous dance, Cantu growing increasingly defensive and Guajardo returning relentlessly to the subject of “what happened.” He reminded her that they were adults and that he kept his personal and professional business separate. He told her that there were no openings in the department but that he would ask his friends if any of them were hiring. Guajardo, for her part, sounded less like a victim as she tried to steer the conversation where she wanted it to go. “But you can understand where I’m coming from. I feel . . . I feel used.”

“No, no, no,” Cantu insisted. “I can’t understand where you’re coming from, but I can relate that you need a job and that you need help. I mean, that’s two different things.”

The sheriff began to get cautious. “Are you recording this?” he asked Guajardo.

“No, are you crazy or what?” she replied. “Why do you feel that way? Okay, forget it, then. When you have a chance, call me, because I don’t want you not to trust me.”

After Cantu hung up, Guajardo turned off her tape recorder.

By the spring of 2003, de Leon was leading a grand-jury investigation into Cantu’s mismanagement of the county jails. In the meantime, she had become entangled in her own political struggle. During her seven years in office, she had amassed both loyal admirers and bitter critics—the former who applauded her commitment to prosecute corruption cases as felonies and the latter who felt that she should allow them to be settled for lesser charges. One such case was de Leon’s felony prosecution of the Harlingen Police Officers Association for making political contributions without filing as a political action committee. Among her detractors was Gilberto Hinojosa, the county judge, who felt she was inconsistent in prosecuting misconduct. Along with the four county commissioners, he had control over her budget and seldom loosened the purse strings. Although her employees were included in the county’s across-the-board raises, only once in her two terms as DA did she get a significant pay raise for her prosecutors. She wanted to convert case files from paper to digital, but the commissioners voted down her plan.

De Leon did not relent. The grand jury finished its investigation in July and took the unusual step of making its report public. “While no indictments were handed down against Sheriff Conrado Cantu,” it read, “there are concerns within his department of such a grave nature that this Grand Jury feels compelled to report to this court the following findings.” The department was marred by “an almost total absence of management” and few checks and balances. Officials placed favoritism over qualifications when they ranked applicants for supervisory positions. Employees were poorly trained and ignorant of state and federal standards. Inmates were allowed to use cell phones and have contact visits on a preferential basis. Accountability was almost nil; employees did not report misconduct for fear of losing their jobs.

Cantu’s press release blamed the messenger. “It is unfortunate that District Attorney Yolanda de Leon has injected herself into the sheriff’s campaign under the cover of the grand jury,” he said. The Democratic primary was scheduled for March 2004, and it was already clear that both Cantu and de Leon would face stiff opposition. His office, Cantu said, had done everything possible to “investigate and bring any wrongdoing to justice.”

The report was the first official condemnation of Cantu during his six years in public office, although Hinojosa and the commissioners’ court had been publicly critical of Cantu about the jail on several occasions. And yet de Leon remained unable to bring any charges. That Cantu continued to elude the justice system was not so much a validation of his honesty as it was an illustration of the web of loyalty that surrounded him. De Leon and her assistants had to resort to using subpoenas to force county employees to cooperate with their investigations. The picture that emerged from their testimonies was that of a sheriff who was a negligent manager and who used his power in less than ethical ways. But it was hard to incriminate him when it was the people working for him who had broken the law.

As local politicking began to heat up, Channel 4 obtained a tape of a jailhouse meeting between the sheriff and jail employees. In the recording, Cantu asked his jailers if they would help him with a campaign block-walking event—a misuse of government property under Texas law. An embarrassed Cantu issued a statement apologizing to his workers in case they had felt pressured. “I can hear how my enthusiasm, or ánimo, can sound overbearing and even demanding,” he admitted. But it was too little, too late. This time, de Leon knew she could implicate Cantu in a crime.

Three weeks before the March 9 Democratic primary, a grand jury indicted Cantu for abuse of official capacity and misuse of government property. The offense was a class A misdemeanor, which carried a sentence of up to a year in jail and a $4,000 fine. Cantu pleaded not guilty and was released on a $15,000 bond. “It’s all politically motivated,” he told the press afterward, his white cowboy hat in hand. “I am innocent.” The case would never come to trial, but the damage to Cantu’s reelection prospects was done. He faced four opponents, including Omar Lucio, the incumbent sheriff whom he had defeated several years earlier.

His world was collapsing. Five more jail inmates had escaped recently, prompting the U.S. Marshals to remove close to three hundred federal prisoners, costing the county more than $2 million in revenue. A week after Cantu appeared in court, an attorney who represented Sandra Guajardo wrote a letter to the county attorney threatening to sue unless they settled for $30,000. Somebody—the attorney will not say who, but it was not the county—promptly paid Guajardo in cash. By then, however, Channel 4 had posted the entire transcript of the sheriff’s phone conversation with her on its Web site.

On that long-awaited election night, when the voters had their say, both Cantu’s and de Leon’s reigns came to an end. Cantu missed a runoff against Lucio by nineteen votes. De Leon was defeated by Armando Villalobos, a defense lawyer and a former assistant DA under de Leon, who had claimed he could run the office better than she had—de Leon had been a delegator instead of a hands-on litigator. His margin of victory was a decisive 2,705 votes. The políticos who wanted de Leon out of office worked hard for the challenger; the county judge, Hinojosa, poured $2,900 into Villalobos’s campaign. Both Cantu and de Leon were now lame ducks. But such were the strange days of Cantu’s term in office that the saga that had roiled the Cameron County Sheriff’s Department in the past years would pale in comparison with what would unfold—unknown to all but a few—in his final, and most corrupt, months.

Omar Lucio bore the badge of sheriff again in 2005, and the residents of Cameron County thought Conrado Cantu was old news. But on a sultry June morning, federal agents arrested Cantu near his home in Olmito. Two days earlier, a federal grand jury in Houston had handed down a 45-page indictment charging the former sheriff with ten counts of extortion, drug trafficking, obstruction of state and local law enforcement, witness tampering, and bribery. It also described the incident in which he had ordered the release of Rodolfo Federico Garza, his friend, after his own deputies had arrested him. (After Cantu left office, Garza paid a $2,000 fine and received deferred adjudication according to a plea agreement.) The indictment confirmed what Garza’s release had suggested: Cantu not only thought he was above the law but had come to believe that he was the law.

The ultimate stage of Cantu’s downfall began shortly after his electoral defeat. Sheriff’s deputies had stopped a truck on the highway and seized $25,000 in purported drug profits. Later that day, the driver made a telephone call to a man he knew could help him: Jerry Garcia, the same person Cantu had picked to run the county’s jail commissary. He asked Garcia if he could find out which law enforcement agency had provided the tip that had led to the seizure. Five days later, Garcia delivered.

Soon, the driver received a second call from Garcia. If he wanted to transport drug proceeds without a problem, he could pay the sheriff $4,000. There were several more calls. More deals were struck. Small amounts of money changed hands. At the driver’s next meeting with Garcia, the sheriff was present. The driver offered $5,000 in cash for the tips he had received and to secure future movements of drug money. Cantu directed him to hand the payment to Garcia. Later that day, Cantu and Garcia met at a Chili’s restaurant, and the money changed hands. A camera’s shutter went off nearby. Neither man had suspected that the truck driver was a government informant.

Assistant United States attorney Jody Young, a popular and well-known figure in Brownsville, had been on Cantu’s tail for eighteen months, ever since a drug probe by the FBI had led to the sheriff. Yolanda de Leon had been working side by side with the feds. Also snagged with Cantu were Jerry Garcia; Captain Rumaldo Rodriguez, Cantu’s chief of criminal investigations, who took instructions from the sheriff on whether to let drug money shipments go through or seize the money; Garcia’s brother-in-law Reynaldo Uribe, who was paid to drive drug proceeds; and restaurant owner Hector Solis, who had asked Cantu to warn him about raids on gambling establishments.

The drug racket had been going on since the first month Cantu had become sheriff in 2001 and had lasted into his very last days in office. In mid-October 2004, Cantu offered to provide the truck-driver-turned-informant with an escort from the sheriff’s office in exchange for 10 percent of the profits. Time was of the essence, he said. The drug runs had to take place during the next ten weeks, before his term expired.

A quiet sense of shame prevailed in Cameron County in the aftermath of its sheriff’s indictment. Cantu had been the fifth border sheriff in the past eleven years to go down for abusing his office. Some shrugged it off with the observation that corruption is an inevitable by-product of power. In an interview, county judge Hinojosa offered an extended list of examples that included former congressman Tom DeLay. One did not have to leave Congress to find other names: Randy “Duke” Cunningham, William Jefferson. Each case of corruption revealed a unique culture of power, with its own web of political relationships. Cantu’s misdeeds, though all too familiar to his constituents, were just part of a much larger picture.

Political administrations in South Texas are not as the rest of the state believes they are: a fated and immutable succession of corrupted leadership. They are instead something like the reigns of Roman emperors or medieval popes: They fluctuate across time between good and bad and everything in between. The reason Cantu’s malfeasances matter is because they laid bare the political culture that enabled him to survive for so long. The fact is that Cantu was not just the villain of local politics but the product of a long tradition that pressures political workers and voters to tolerate criminal and ethical infractions so that insiders can maintain their way of doing business. Indeed, most of the political insiders in Cameron County—most notably Hinojosa—preferred Cantu, who represented the worst of the culture, to de Leon, who tried to reform it. But the culture did not want to be reformed. And no one knew that better than de Leon.

“How do we make decisions?” the former DA said as she reflected on Cantu’s rise and fall. “Is it based on how a person smiles, how he greets you? Is it based on whether they remember your name and call you by your name? That they inquire about your family? Is that all that we want? Is that all that we need?”

On July 8, 2005, Cantu pleaded guilty to racketeering in federal court, as did his codefendants. He and Garcia had received nearly $50,000 from drug traffickers and undercover sources. On the day of their sentencing, they all had a chance to speak before the judge. What Cantu chose to say was both revealing and painful to observe. He launched into a rambling and highly emotional defense of everything that he had been accused of during his tenure, including the jail breaks and sex scandals, which had nothing to do with his crime. He blamed the press. Envious law enforcement agents. Dirty politicians. Alcohol. It seemed that Cantu was the last person who still believed in his self-created image.

“Maybe I wasn’t educated enough for this position,” he said, choking on his tears. “Maybe I wasn’t prepared enough.” Then he blamed Garcia. “I was influenced by a man that did wrong, and I’m not saying it’s his fault. It’s mine. I should have stopped, but I couldn’t. I was lost. I was totally lost.

“I’m a different individual,” he went on. “This is the real Conrado Cantu, the man that has passion and love and writes songs. I have a charisma. I love to share my love with people, my ideas. I have a lot to offer if you could send me to a place where I can be productive, to speak at the schools, police academies, and educational programs, where I can help the community back and make it up to them. I’m not a bad person. I’ve never hurt anybody maliciously . . .”

But the man who had been so adept at telling people what they wanted to hear did not move the judge. “You promoted disrespect for the laws of the State of Texas and the United States in spite of the fact you were sworn to uphold those same laws,” she said. “You engaged in conduct that allowed drug traffickers to work without fear of law enforcement from the time that you entered office until you left in 2004. . . . The fact of the matter is that, instead of using your charisma to help the community, your self-professed charisma, you used your charisma to betray your community.”

His fate was decided swiftly. The judge sentenced the sheriff to 24 years and 2 months in a federal penitentiary. At age fifty, Cantu faces what amounts to a life sentence. He and his attorneys were stunned; they had expected more-lenient treatment. They announced their intention to appeal. But this time, the story of the people’s sheriff was really over.