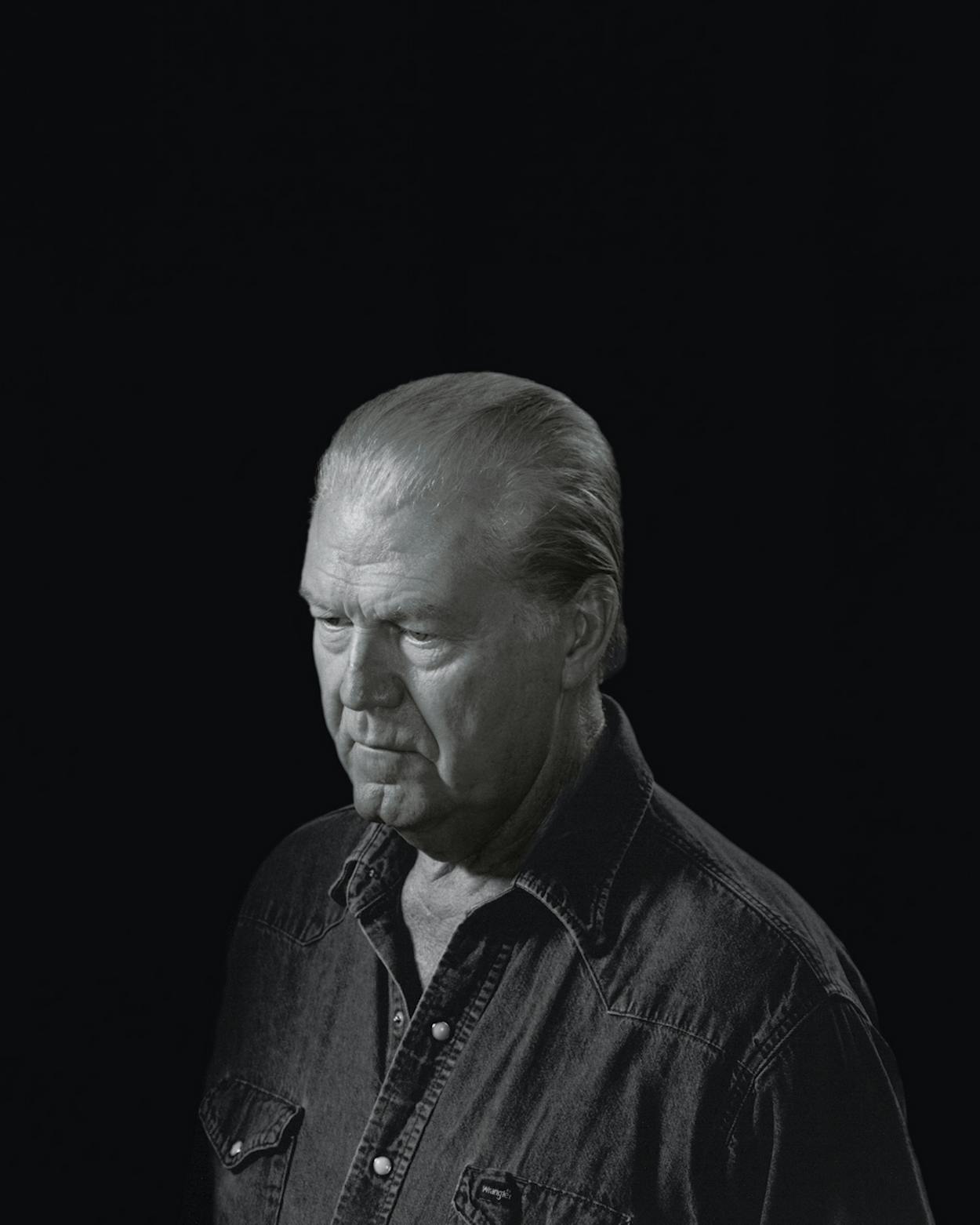

BILLY JOE SHAVER ACTS MORE like a Baptist preacher than a man in need of salvation. Performing at Austin’s KUT-FM studios, he waves his arms around as if he were trying to explain something. He pounds his chest and kicks his leg out. He clasps his hands like a minister, throws punches like a fighter. One minute he’s standing still, slightly tilted to the left, hands in his pockets, eyes slammed shut as he sings, deep worry lines between his brows. The next minute he’s so riled up his face burns bright red. He stretches out his long arms as wide as they can go, revealing that the index and middle fingers on his right hand are stubs and the ring finger is missing a joint. He can’t hold a pick, and when he plucks his guitar, he uses his thumb and pinkie. Billy Joe, who is 64, is wearing blue jeans, a blue denim shirt, brown boots, and a brown cowboy hat, which, when he takes it off to wave in the air, sets his longish gray hair loose. He looks like a crazed George Washington, gesturing at the ceiling, clenching his fist.

The funny thing is, he’s singing to a radio audience that can’t see any of this. Here in the studio at the University of Texas at Austin, there are only three people besides Billy Joe’s four-piece band, which he is leading through a one-hour set of songs about love and death and trains and trouble. He does some good-natured preaching and storytelling. He introduces one of his best-known songs by saying, “This is a song that helped me when I was at the end of my rope. It’s called ‘I’m Just an Old Chunk of Coal (But I’m Gonna Be a Diamond Someday).'” After a beat of dead air, he adds, “Still trying.” As he sings the country shuffle, his Waco accent gets even deeper on some of the verses, hiccuping the lines: “I’m gonna glow and grow ’til I’m so plu-pure-perfect . . .” Toward the end of the set, he does a song called “Live Forever” and, unknown to the audience, ends the song on his knees, hands at his side, head bowed in silence.

With time for one more song, the show’s host asks Billy Joe to play the title track from his latest album, Freedom’s Child. “I would,” says the singer, “but I’d rather do this one about Jesus. Like I say, ‘If you don’t love Jesus, go to hell.’ May the God of your choice bless you—and good luck with that.” He and the band chug into “You Just Can’t Beat Jesus Christ,” the song Billy Joe ends almost every set with, whether he’s playing on the radio in Texas or the stage in New York City. He sings it like a gospel singer would, answering the title’s affirmation with ejaculations like “Oh, no, you can’t.” The show ends, and as soon as he is off the air, Billy Joe says to no one in particular, “I thank Jesus Christ every chance I get.”

“Aw, you’re just buttering up the boss,” responds Cornbread, his bass player.

“I wouldn’t kiss his ass,” responds Billy Joe, “if I didn’t have to.”

Then, after a pause, he adds, “And I have to.”

BILLY JOE SHAVER, David Allan Coe, Johnny Paycheck, Jerry Jeff Walker, Kris Kristofferson, Mickey Newbury—they were the “boys” with whom Willie and Waylon sang about going to Luckenbach, the so-called outlaws, the musicians and songwriters who, in the early seventies, revitalized country music by stripping it down and bringing it back to its roots. It was a hell of a crew, a wild bunch of drunks and crazies—and great songwriters. By most accounts, even Willie’s, Billy Joe was the greatest. “Billy Joe is definitely the best writer in Texas,” says the braided one. By most accounts, he was also the craziest.

So it’s fitting that his own life resembles a country song, though one that Hank Williams might have written if he’d collaborated with, say, Sophocles. “The Ballad of Billy Joe Shaver” goes something like this:

First verse: His father leaves before he’s born, and he’s raised by his grandmother while his mother waits tables in a honky-tonk.

Second verse: He gets kicked out of the Navy, marries his pregnant girlfriend, and almost gets his right hand hacked off.

Chorus: He’s a screwup and a scoundrel (drugs, booze, women) who someday, if lucky, will redeem himself.

Third verse: He leaves his wife and becomes a successful Nashville singer and songwriter. He does more drugs and hits rock bottom.

Fourth verse: He becomes born again and moves back to Texas, but he can’t get a gig. His son joins his band, rejuvenating his career.

Repeat chorus.

Fifth verse: His son dies of a heroin overdose, not long after his wife (whom he’s remarried—twice) and his mother die of cancer. He gives up music.

Sixth verse: He decides to try again, but he has a heart attack onstage and almost dies. Alone in the world except for his songs, he goes back on the road.

Repeat chorus, doubling the lines about the hope of redemption.

Not only is Billy Joe’s song true, but unlike almost everything coming out of Nashville these days, it has the ring of truth, in all its glory and infamy. Billy Joe’s life has imitated his art, and vice versa, for so long it’s hard to tell where one starts and the other ends. He was born in Corsicana, a cotton-gin town fifty miles southeast of Dallas, on August 16, 1939, to a laborer named Virgil and a woman named Victory, though by then Virgil was long gone. Victory left Billy Joe with his grandmother Birdie Lee Watson while she moved to Waco and went to work in a bar called the Green Gables. Birdie Lee was dirt-poor, making lye soap for money, and raised Billy Joe and his older sister, Patricia, on her old-age pension. He would go across the railroad tracks to the black settlement in Corsicana and listen to singers and guitar players, and at night he would tune his radio to the Grand Ole Opry and Louisiana Hayride. Birdie Lee got him a guitar and told him, rocking him in a rocking chair, that someday he was going to play on the Opry, which was about as big as a Corsicana kid could dream.

Billy Joe was a sensitive boy who wrote poetry and songs, and when he visited his mother in Waco, he would sometimes get up on the tables at the Green Gables and sing. He was also quick to anger and got in a lot of fights. He joined the Navy at 17 but was thrown out for punching an officer. He spent the next six months in a New Hampshire prison and ultimately got his discharge changed to “honorable” (the officer was wearing civilian clothing and he had hit Billy Joe first). He returned to Waco and married his teenage girlfriend, Brenda, after she got pregnant. He was tall and strapping and found work picking cotton, roughnecking, and cowboying in a rodeo to support her and their baby son, Eddy. The couple fought a lot—”Hellacious knockdown drag-outs,” Brenda once told an interviewer. At 21 he cut off most of two fingers and part of a third in a sawmill accident and had to pick them up and drive himself to a doctor, who wasn’t able to do much but stop the bleeding.

The accident convinced Billy Joe that he wasn’t suited for hard labor. “I wouldn’t ever have gone into music if I hadn’t lost my fingers,” he says now. “It led to a bunch of weird dominoes falling in a weird order.” The real-life country boy decided to become a professional songwriter, but he didn’t know where to go or what to do. He had seen Willie Nelson play in clubs around Waco, and he eventually got up the nerve to talk to him. Willie wrote “Good luck with your songs in Nashville” on a matchbox, and Billy Joe took that as a sign. In 1966 he took his guitar, songs, and lady-killer’s smile and hitchhiked there, leaving Brenda—who didn’t think he could make it in music—and Eddy behind. He and Brenda were soon divorced.

Billy Joe soon returned to Waco, defeated by Music City’s indifference, and spent the next several years traveling back and forth between Texas and Tennessee, eventually finding the courage to breach Nashville’s inner circle. Once, he rode a motorcycle up on the front porch of songwriter Harlan Howard’s publishing company and announced that he, Billy Joe Shaver, was the greatest songwriter who’d ever lived. Howard, a Nashville legend who had written classic songs such as “I Fall to Pieces” and “Heartaches by the Number,” invited him in for a drink.

By 1968 Billy Joe had a job with singer-songwriter Bobby Bare’s publishing company and began churning out songs. He got to know some of the other Nashville outsiders, guys like Kristofferson, with whom he shared the handsome-scruffy-hippie-poet MO. And the wild life suited him well. He did a lot of drinking, did a lot of drugs, and raised a lot of hell. “Drugs, doping, smoking, women,” he says. “All kinds of drugs—speed, coke. I tried heroin once. The girl shot me up and it didn’t do nothing. I was so goddam crazy. I was crazier than any of them. I went for it.”

He stayed in touch with Willie, who invited him to play at his first Fourth of July Picnic, called the Dripping Springs Reunion, in 1972. After Billy Joe had played, he and some others were passing the guitar around backstage, singing songs. Billy Joe played one of his called “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me.” Waylon Jennings, who was often high on cocaine, liked it so much that he enthusiastically vowed to do a whole album of Billy Joe’s “cowboy” songs.

Billy Joe stalked Waylon for six months, reminding him of his drug-addled promise, finally cornering him in a Nashville studio, where he was recording his next album. As Waylon explained to an interviewer a few years before he died, Billy Joe was drunk: “He said, ‘You told me you was gonna do my goddam songs. Now are you gonna do ’em or am I gonna have to whip your ass?'” Waylon eventually sat down and listened to the songs, which had titles like “Honky Tonk Heroes” and “Old Five and Dimers Like Me,” and was astonished. This was soul music for rednecks, koans from a honky-tonk lifer, with simple melodies and emotional, evocative words. Some were pure poetry: “I’ve spent a lifetime making up my mind to be/More than the measure of what I thought others could see” went the first lines of “Old Five and Dimers Like Me.” Some were just songs about ragged old trucks and one-night stands. But all were from Billy Joe’s life, things he had done or dreamed about, so they sounded true.

Waylon changed the course of his album right then; all but one song would be Billy Joe’s. The resulting 1973 record, Honky Tonk Heroes, was the Never Mind the Bollocks Here’s the Sex Pistols of the outlaw country movement. All of a sudden country was cool. String sections and sequins were out, spare arrangements and blue jeans were in; the wet-head was dead, and real men grew beards and long hair. Hippies mixed with rednecks. And Willie and Waylon became big stars. Soon came Red Headed Stranger and “Luckenbach, Texas” and Wanted! The Outlaws, the first Nashville platinum album. Forget that the term “outlaw” was thought up by a publicist or that the notion of a gang of musicians hanging out and rebelling was just silly—the formula worked. And the songs were good.

Especially Billy Joe’s. After Heroes, he was covered by Kristofferson, Bare, and Tom T. Hall; later came Elvis, the Allman Brothers, and John Anderson. They all heard the same thing in Billy Joe’s writing. “His songs are so real,” says Willie. “And Texas. They’re pieces of literature. Everything he writes is just poetry.” Success bred even more excess for the wide-eyed rogue, yet he also found himself drawn back to Brenda, whom he remarried. (She moved to Nashville and became a hairstylist for, among others, the late Johnny Cash.) In 1973 Billy Joe began releasing country albums of his own starting with Old Five and Dimers Like Me, singing in his Central Texas baritone about living hard and raising hell, all with that lazy, stripped-down, pot-smoking country feel. He moved from label to label—Monument, Capricorn, Columbia—but his performing career never got off the ground, and he considered quitting the business. In 1977, after another typically wild Nashville night, he had a terrifying vision of a silent, disapproving Jesus, with eyes glowing like red coals, sitting on his bed. Billy Joe went walking and found himself on the top of a cliff, trying, he thinks, to kill himself. Instead, he says, he was saved by Jesus. On his way down, the words and melody to a new song, “I’m Just an Old Chunk of Coal,” started coming to him. He moved the family to Houston and went cold turkey on all his vices, but by the end of the decade, he and Brenda were divorced again. His career, by then, seemed over too.

In the mid-eighties Billy Joe found rejuvenation in an unlikely place: his broken home. Because of his wandering ways, his son, Eddy, had been raised mostly by Brenda. Now Eddy had grown up, and he was a gifted guitarist, a blues guy and a rocker schooled by, among others, the Allman Brothers’ Dickey Betts, who had given the boy a guitar when he was twelve. Billy Joe started playing with his son, and Eddy co-produced his father’s 1987 album, Salt of the Earth. Then, after Eddy spent time playing with the Allman Brothers, Dwight Yoakam, and Guy Clark, father and son started their own band, Shaver, and created their own sound, a roadhouse boogie with honky-tonk twang.

Billy Joe’s career was reborn. Shaver began touring constantly; they also released seven albums for four labels, including Tramp on Your Street, in 1993, which sold more than 150,000 copies. The two grew their hair down to their shoulders, and with similarly coiffed drummers and bassists, Shaver looked like a Texas version of Lynyrd Skynyrd. “We were good,” Billy Joe says. “Probably too good. Every show we did was perfect.” Some of his fans would say that this is a father’s love talking; they thought his rocker son played too loud, too fast, and too often, stepping on the melodies and into the quiet spaces of Billy Joe’s songs. Billy Joe didn’t hear or didn’t care; he was loyal to the son he had once neglected, and together they were creating something new. Their band was integral to the rise in the mid-nineties of the Americana movement—rootsy, traditional-country-influenced rock and roll and so-called alt-country—which helped invigorate the careers of other old-timers too, especially Cash. It was a music for underdogs, and Billy Joe was the perfect saint for it, getting treated like a beloved grandfather by such magazines as No Depression. He was also discovered by new country acts like Pat Green, who covered his songs and proselytized about his influence.

But Eddy was truly his father’s son. He got hooked on heroin, an addiction he fought for years, and took a turn for the worse after his mother died of cancer in the summer of 1999 (she and Billy Joe had remarried a second time in 1997). “He went into a tailspin,” says Billy Joe. “They were like brother and sister. She was only seventeen when he was born.” On December 30, 2000, Eddy was found in a motel room unconscious from an accidental overdose and was taken to the hospital; the next day he died. He was 38. Shaver had a New Year’s Eve show scheduled for that night at Poodie’s Hilltop Bar and Grill, in Spicewood. Billy Joe did it, with help from Willie, who put a band together for him and wound up playing more than Billy Joe, who mostly sat in the audience, consoled by friends. “Your normal cowboy wouldn’t even have attempted to do it,” says Willie. “Billy Joe is tough. They don’t come much tougher.” For Billy Joe, it was the longest night in a life full of them.

“PLEASE DO NOT DISTURB,” READS the handwritten note taped to the screen door of the unassuming brick ranch house in a south Waco suburb. “I haven’t slept in 2 days—Billy Joe.” The white paper is faded from two and a half years worth of Waco sun and rain. “It’s been up since Eddy passed,” he says on a warm June day as he opens the door. The inside is dark and cluttered, and the only life comes from two pit bulls. “The dogs own it,” he says. “I just live here.”

The kitchen table is crowded with a fax machine and stacks of unruly papers. Tacked on the wall is a tour itinerary for the next three months. There are forty dates, everything from a private party at the YO Ranch, near Kerrville, to a show at the downtown Centennial Plaza in Midland to Willie’s Fourth of July Picnic. Billy Joe spends a lot of time on the road with his band, most of whom are musicians half his age. It’s a hard, unglamorous, and expensive life. In fact, Billy Joe loses money touring, taking his songwriting royalties and paying for the musicians, the van or bus, motels, and food. “I pay to play,” he says. “But I love the road.”

Along the fireplace are small stone monuments, sent by a fan, with Billy Joe’s lyrics inscribed on them. There are also various Indian artifacts, and above the mantel are photos of Eddy and Brenda, who died only three months after Victory died. The truth is, Billy Joe says, he’s the one who should be dead. He was the one prone to fights and being in the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong people, doing something stupid because, well, that’s just what you did when you were a hell-raiser. “We always figured I’d be the one to go first,” he says. “We figured I’d never live to see forty. I had insurance out the ass on me—didn’t buy it on either of them.”

Billy Joe’s wife, the woman he married three times and divorced twice, was his muse. “Every love song I’ve ever written was about her,” he says. And as for his best friend and partner, Eddy, who died of the bad behavior his father had somehow navigated, Billy Joe is still devastated. He knew about Eddy’s addiction but figured his son would conquer it. “I just assumed it would be all right,” he says. “He did probably look at me and say, ‘If Dad can do it, I can too.'” After a long pause, Billy Joe sighs. “You never get over it.”

One song the two wrote together, “Live Forever” (Eddy wrote the music), is a transcendent work that sounds like an old bluegrass hymn:

I’m gonna live forever, I’m gonna cross that river

I’m gonna catch tomorrow now.

You’re gonna wanna hold me, just like I always told you

You’re gonna miss me when I’m gone.

Nobody here will ever find me

But I will always be around,

Just like the songs I leave behind me

I’m gonna live forever now.

After Eddy died, Billy Joe actually quit writing songs for the first time in his life. He also lost the urge to perform. It wasn’t until six months later, when his old friend Kinky Friedman persuaded him to join him for some Texas shows, that he got back onstage. During one of those performances, at the hot, stuffy Gruene Hall on August 25, 2001, Billy Joe got a collect call from God. It was a heart attack, live and onstage. Billy Joe remembers it well. “I said, ‘Thank you, Lord, for letting me die in the oldest honky-tonk in Texas.’ I wanted to die. All this had happened, and I was going home to see Eddy, Brenda, and my mother.” He survived and was then faced with a three-week Australian tour with the pushy Friedman. “I told him, ‘I can’t go. I had a heart attack.’ Kinky said, ‘So what? You’re going to ruin my career.'” So Billy Joe went. Two days after coming home, he had quadruple bypass surgery.

The songwriting finally started coming again last year after producer R. S. Field, who had helmed Tramp on Your Street, enticed Billy Joe to record again. He wrote a couple dozen songs, which were whittled to the thirteen on Freedom’s Child, a shimmering little autobiographical masterpiece, part country, part jangle. The album is proof that Billy Joe can still write a song. In fact, looking back over his work from the past decade, in some ways Billy Joe has actually gotten better as a writer as he has gotten older. Though he’ll never top the youthful drive of “I Been to Georgia on a Fast Train,” it’s hard to imagine a more perfect love song than “Star in My Heart” or a more perfect religious haiku than “Son of Calvary” or a funnier send-up than “Leavin’ Amarillo” (“Screw you, you ain’t worth passin’ through”)—all three written in his second half-century. “I think I was born to write songs,” he says. “That’s why my eyes and ears are so open. But I can control it now. In the early days I couldn’t stop ’em. It was the master of me. Now I’ve mastered it—I’m a master songwriter.”

Now, as then, Billy Joe writes only about what he knows personally, yet he somehow takes the specific and makes it general; you don’t have to have lost a son and a wife to feel the heartache of “Day by Day,” the story of his family on Freedom’s Child. Many of his songs are mea culpas about the past—his irresponsibility, his neglect of people close to him, his pursuit of pleasures of the flesh: “I been a drifter and a low-life loser,” he sings on “Love Is So Sweet,” “you can learn a lot from me . . .” Sometimes the old Billy Joe pops into one of his songs just long enough to seduce some woman or get in a fight. Part of his charm, at least in his songs, is that he keeps doing the bad stuff even though he knows it’s bad. “He’s absolutely honest,” Kristofferson says. “Clear-eyed, no guilt, not a bit of artifice. That’s why his songs have lasted.”

Last year Billy Joe finally got some recognition from the industry when, at the Americana Music Awards ceremony, he was given the first Lifetime Achievement award for songwriting. It was, he said from the dais, the first award he’d ever received. And now, at an age when many of his peers are dead or retired, the wise old songwriter seems, as they say in showbiz, poised. He tours relentlessly with a great band. He’s working on his autobiography with writer Brad Reagan, and he’s also working on a collection of poems. And then there’s the documentary shot by Luciana Pedraza, an Argentinean horsewoman and tango dancer, with the help of her boyfriend, Robert Duvall. Duvall, who met Billy Joe in Texas during the filming of Lonesome Dove, cast him as a recovering alcoholic in The Apostle in 1997. Pedraza was fascinated by Billy Joe’s life and songs. She spent three weeks following him around with a camera and even interviewed his 102-year-old English teacher, Mabel Legg, who recited from memory a few of his poems, including “Space,” which he wrote at thirteen. The documentary is done, and Pedraza says it will be out in February, in time for spring festivals.

In the meantime, Billy Joe’s life is defined by two things: playing and sitting around at home waiting to play. All roads lead away from Waco, and he longs to be on them. “I love to travel,” he says. “I love to play. I love that freedom, the only free place I’ve got left.”

LAST SUMMER BILLY JOE PLAYED Willie’s Fourth of July Picnic to about the same number of people he played to 31 years ago: kids, bikinied teens, college students with baseball caps turned backward, middle-aged women who sang along, men with gray beards who hollered and waved their hats. During Billy Bob Thornton’s set before his, they chanted, “Billy Joe! Billy Joe!” The chant resumed as his band set up their amps; Billy Joe went to the lip of the stage, took off his hat, and waved at the crowd, his face set in a wide grin. Most stars wouldn’t be caught dead onstage before showtime, but Billy Joe’s fans are his last best hope. When the band started, he became like a great soul singer in a church of his own design, completely at ease, smiling, expansive, open to everything and everyone. He told funny stories and waved his hands like a preacher. He threw punches on “Honky Tonk Heroes” and got down on his knees and bowed at the end of “Live Forever.” He played “You Just Can’t Beat Jesus Christ” and gave his Zen-like benediction: “May the God of your choice bless you.”

It took him awhile to get back to his bus after the show; in the backstage area, there were just too many people to hug, to reminisce with, and to hear words of solace from. He spent some time visiting with an old friend inside the bus, a man he hadn’t seen in some time, another ex-drunk who had to quit the wild life to save his own and who told Billy Joe every detail. After a while they said good-bye (“I love you, brother”; “I love you too”) and Billy Joe said, “It’s gonna be all right. It’s a fifteen-rounder, not a twelve-rounder.”

Billy Joe went back outside and was stopped by two young women who had been looking for him for half an hour or so. They threw their arms around him, and he stood between them, hugging and laughing. Another woman, a little older, also approached and handed him a piece of paper she had written something on, which he put in his pocket. Soon a small crowd had gathered—old friends, musicians, backstage drifters—and he was surrounded, disappearing from view except for his brown hat, which seemed bowed in gratitude.