“They had only one thing to do, and they didn’t do it.” That’s the epitaph of the regular session of the 70th Legislature. The task, of course, was to solve the state’s budget crisis. They didn’t even come close. In fact, the three leaders-Bill Clements, Bill Hobby, and Gib Lewis-couldn’t agree on how much the state is spending in 1987 until seven days after final adjournment.

The failure to deal with the budget overshadowed everything else that happened this session. In fact, the best news may have been something that didn’t happen: The piles of bills aimed at emasculating the education reforms of 1984 never got unstacked. No pass, no play remains intact. So does the career ladder for teachers. The only setback was the loss of mandatory subject matter testing of teachers, something pusillanimous politicians had long ago abandoned anyway.

Positive accomplishments are not so easy to find. The Legislature did act on four high-profile issues—deregulation of trucking and AT&T, abortion, and, n a brief special session, tort reform. Whether it acted meaningfully is another question. The deregulation bills merely flipped the decision from the Legislature to a couple of state agencies that have had the power, but not the inclination, to deregulate their industries all along. The abortion ban applies only to third trimester abortions and only some of those. The tort reform-insurance reform package is the strongest of the four, but it is far short of what its backers envisioned at the start of the session.

As disturbing as the lack of progress was the deterioration of process. Whatever happened to the old-fashioned notion that members of the Legislature are supposed to come to the Capitol and vote? No one wanted to cast a controversial aye or nay this session. And so the concept of the shotgun compromise was born. Legislators and lobbyists with controversial bills were sent off to back rooms and told to negotiate with their opponents. If they didn’t reach an agreement, there would be no vote. The Legislature’s function became not to debate but to ratify. “I’m so tired of being told ‘Work it out,’” said one lobbyist. “The next time I get a request for a campaign contribution, I’m going to say, ‘Work it out with your opponent first.’”

Perhaps the Legislature is just plain worn out. The regular session really began last summer, with the two special sessions to raise taxes. The mood of those sessions, characterized by partisan enmity, carried over to this year. Now the odds are good that the budget crisis will keep lawmakers in session most of this summer. A year-round session: the Legislature is working as long as Congress, for a tenth the pay.

All these factors made our task of compiling the list of Best and Worst Legislators more difficult than usual. We followed the session in the House and in the Senate, in committee and on the floor; we talked to legislators, staff, lobbyists, and members of the Capitol press corps; we were there for the post-midnight sessions on the budget; and yet the nature of the session was such that we saw few opportunities for heroics or villainy. Our lists, therefore, revolve more around personality than events. They are primers on why some people succeed and others fail at the art of politics.

Our criteria are the same that legislators use to evaluate each other. No ability is more prized by a politician than his skill at judging people. (A former legislator named Sam Johnson once told his son, Lyndon, “If you can’t walk into a room and tell right away who’s for you and who’s against you, you have no business in politics.”) Legislators don’t want to know whether a colleague is conservative or liberal; they want to know whether he is open- or closed-minded, smart or dumb, honest or venal, industrious or lazy, trustworthy or treacherous.

A legislator on the Best list uses his good qualities to the fullest. He wants to be at the center of action, and his colleagues want him there. He must be a student of the process—its rules, its rhythms, its reins of power—and the better student he is, the more respect he earns. Negative qualities alone are not enough to relegate a legislator to the Worst list. It is the aggressive use of badness that is fatal.

The changing character of the Legislature is reflected in the high turnover on our Best and Worst lists. Only senators Ray Farabee of Wichita Falls, a Best, and Craig Washington of Houston, a Worst, reclaimed their places. The people who joined them were very different from their counterparts of 1985. The nine new Bests did not dominate the session as their predecessors had done, but they were a hardier species who thrived in poorer soil. The new Worsts, on the whole, are less malevolent than the group they replaced-misfits instead of roadblocks. Maybe that’s because there can’t be any roadblocks in a session that has no traffic.

The Best

Kent Caperton, 37, Democrat, Bryan

This was a session when nothing happened, when nihilism seemed to be the guiding principle. Only someone forgot to tell Kent Caperton. Short and baldish, with and impish smile and unprepossessing presence, Caperton is a bantamweight with a heavyweight’s punch, the dominant senator of the session.

His list of accomplishments included strengthening the Open Meetings Act, at which he has labored for years; cosponsoring the successful trucking deregulation bill; killing one of the session’s worst proposals—a bill to exempt industry from air pollution inspections; getting an alimony bill through the Senate (it died in the House); and offering the budget amendment that restored higher-education funding to its 1985 level, thus setting the terms for that part of the budget debate.

And that’s just what he did in his spare time. His heaviest labors took place over tort reform. He and sponsor John Montford of Lubbock spent hundreds of hours negotiating a compromise that could pass a sharply divided Senate, in the face of the common wisdom that they were wasting their time. The common wisdom was wrong.

Their meticulously crafted compromise largely reflected Caperton’s opposition as a plaintiffs lawyer to restrictions on personal injury suits, and it sailed through the Senate. In conference committee with the House, which had produced a version more favorable to defendants, Caperton proved how formidable (okay, many would say obnoxious) a negotiator he could be. But if a successful compromise means no one is completely happy, Caperton has a right to be less unhappy than anyone else.

Caperton is among the most independent of legislators. Though he has been targeted by Republicans, he doesn’t look over his shoulder at his district, and he manages to carry a legislative program that is pro-environment, pro-consumer, and strong on women’s issues. And he broke with the powerful Texas Trial Lawyers Association by supporting merit selection of judges, a position that most plaintiffs lawyers (who are big contributors to judicial election campaigns) oppose.

Even if Caperton did go overboard late in the session on his tendency toward preachiness, at least he had plenty to preach about.

Eddie Cavazos, 44, Democrat, Corpus Christi

A court jester who became a prince. No member of the House did more to advance his standing this session than Cavazos. At the beginning he was hardly known outside the Hispanic caucus. At the end he was a feared adversary in floor debate and a major inside player-one of five House members on the powerful conference committee to negotiate the state budget.

The weapons in his arsenal were (1) a tension-busting wit (when House and Senate budget writers couldn’t agree on anything, even when to work on the weekend, Cavazos said, “We’ll split the difference-you work Saturday, and we’ll work Sunday”) and (2) a keen sense of how to make points without making enemies. During the floor debate over the appropriations bill, Cavazos fought an amendment to transfer money from state colleges and universities to nursing homes. Rather than polarize the issue by arguing that higher education was more important, Cavazos asked, with a puzzled air, how much the amendment cut from each college in the state. As the lengthy roll of cuts and colleges was read, every legislator with a school in his district got the message. It was the cleverest kill of the session.

Cavazos has the gift of being funny even when he’s serious. When senators wanted to hire more inspectors for state purchases, he shifted his rotund body, scratched his bald head, and asked bemusedly why the person who orders the supplies can’t inspect them. Everybody chuckled—and cut the inspectors. It’s hard to know whether he cracks jokes to make up for a lack of knowledge, but in practice it doesn’t matter. The Legislature is not a debating society; it’s more like summer camp, and everybody wants to play with Eddie.

Ray Farabee, 54, Democrat, Wichita Falls

Poor Farabee, everybody kept saying. He’s having his worst session. Well, maybe he did. When you’ve spent a decade in the rarefied air of the Senate’s ionosphere (this is his fifth appearance on the Best list), you can’t fall back to the stratosphere without causing talk. But from our vantage point on the ground, he’s still pretty high up there.

Certainly there was no drop-off in his work load; he had more credits than Laurence Olivier. Without fanfare, Farabee labored on the cutting edge of the state’s biggest problems: prisons (he overhauled the much-lambasted parole system), tort reform (he provided badly needed protection from lawsuits for charities and their directors and volunteers), AIDS (he revised the state’s communicable disease laws, establishing how to test for and report AIDS), and state debt (with the investment community getting nervous about Texas’ financial condition, he established a bond review board to get the state’s fiscal house in order).

Nor did he fail to exhibit his usual scout’s oathful of virtues. In the ill-fated conference committee on the budget, which degenerated into a Babel of name-calling and rhetoric between House members and senators, Farabee steered the discussion away from personalities and back to numbers. When his own bills came under attack in the Senate, he lived up to his nickname, “Fairabee,” by being quick to compromise. His bill allowing flexibility in rate setting of local telephone service started out as highly controversial; after Farabee agreed to amendments backed by consumer groups, it passed with hardly a murmur.

So what went wrong? For one thing, his major issue, merit selection of judges, never got off the ground. For another, he suffered a rare public humiliation when a utility bill he carried proved to be full of mousetraps for consumers and went down to a 20-10 defeat on the Senate floor. Most obvious, however, is that Farabee is no longer looked to as the role model for what a senator should be. He is calm, deliberative, concerned above all about what’s best for Texans. The torch has passed to a younger group that is highly partisan, intensely ambitious, and given to showboating and political gamesmanship, and the Senate and the state are the less for it.

Bruce Gibson, 33, Democrat, Godley

The unlikely savior of tort reform. He didn’t sponsor the bill, and for most of the session he didn’t know much about the issue. Yet at the crucial moment he saw the need for an intervenor, took a cram course, inserted himself in a vicious dispute, shaped the issue to his vision, and won through tireless persistence.

Here’s the story:

Chapter One (in which our hero gets involved). The Senate passes a watered-down version of tort reform. Gibson sees House sponsor Mike Toomey pressing for a tough House bill to use as a negotiating tool. Gibson decides that it is bad strategy. Plaintiffs lawyers, who oppose tort reform, have too many loyal followers in the Senate to be intimidated. Meanwhile, House members will have to vote for one side or the other, making powerful enemies either way, when a compromise is the best that can be hoped for in the long run. Gibson asks to be named chairman of the subcommittee assigned to study the bill. He is.

Chapter Two (in which our hero earns his spurs). Under Gibson the subcommittee fashions a compromise. The House passes it after a strong floor speech by Gibson helps Toomey fend off a lethal amendment. The bill goes to a House-Senate conference committee that includes Gibson. One week is left in the session.

Chapter Three (in which all seems lost). Senate conferees spend five days pouting. They ignore three House offers. Forty-eight hours to go, no movement toward a compromise. The Senate makes its first offer. No progress. Twenty-four hours to go. The meeting breaks up with tempers flaring. The word passes through the Capitol: tort reform is dead. Everybody except Gibson is ready to call of the negotiations. Gibson urges one last meeting in the morning of the session’s final day.

Chapter Four (in which hope is restored and lost again). Fourteen hours to go. Toomey is boycotting the morning meeting. Looking for the right mixture, Gibson offers another deal. Nine hours left. The Senate finally gives a little. Tempers grow short again. Eight hours left. Gibson and Senate sponsor John Montford start trading and reduce their differences to three. Four hours left. Just two issues to decide. Tempers explode. Toomey throws in the towel, heads for the door to entomb tort reform at a press conference.

Chapter Five (in which all live happily ever after). But Gibson reaches out, grabs him by the coattails, sits him back down. Talks renew. Minutes later, there’s a deal.

Bob Glasgow, 45, Democrat, Stephenville

At last he shed the curse of “potential” and joined the Senate’s first rank. Everybody counted on Glasgow this session: fellow senators, who relied on his acute legal mind for help in drafting their amendments; Bill Hobby, who made him the Senate’s point man on taxes; and the lieutenant governor’s staff, who depended on him to catch dangerous flotsam and jetsam in the last-minute flood of legislation.

If Glasgow had been a truck, he’d have been over the weight limit. He was one of the session’s premier bill passers: His final tally sheet showed 64 bills sent to the governor, including an economic development package, and three constitutional amendments. He was also one of the premier bill killers. In the closing hours of the session he discovered dubious language in a child support bill and killed it on a point of order. It turned out that the portion of the bill that disturbed Glasgow included efforts of two House members to settle custody disputes with their ex-wives.

His grandest moment was a devastating attack on a bill deregulating AT&T. In the Senate, where rules require that a bill must be supported by two thirds of the members before it can be debated, it is next to impossible to change the fate of a bill on the floor, but Glasgow was part of a team of senators who did it. Attacking AT&T’s assertion that the bill would lower rates, Glasgow thundered, “Those of you who are voting for this bill, you tell me someone who has told you this is a good bill besides a lobbyist. This is the number one worst bill I’ve seen since I’ve been in the Legislature.” Glasgow’s oratory helped cement the fragile coalition that succeeded, by margins as narrow as one vote, in attaching crippling amendments to the bill.

Juan Hinojosa, 41, Democrat, McAllen

Watching Juan Hinojosa work the legislative process is like watching a professional plate spinner—as soon as you think one of those plates is about to fall, he dashed back and gets it moving again. In a session in which most members’ efforts resulted in broken crockery, Hinojosa hardly caused a chip.

What distinguishes Hinojosa is that he uses his insider’s skills and his considerable personal charm to advance one of the more unusual agendas: legislation that will improve the lives of Texans who need someone to look out for them. These include women with abusive husbands (they were being charged up to $200 for protective orders; Hinojosa reduced it to $36); parents of newborns or sick children (his plan to give government workers unpaid leave passed the House but died in the Senate); rape victims (they will now be able to use a pseudonym in court proceedings); and children involved in custody disputes (judges must now consider evidence of parental violence in custody cases).

Whether bills like these become law depends upon how good the sponsor is. No powerful lobbyists labor on their behalf. Enemies are poised to kill them on a whim. Hinojosa succeeded because he is a master of the process. He has traveled the secret passages around the dreaded House Calendars Committee known to only a few (one opponent thought he had killed the protective order bill in Calendars; Hinojosa then attached it to another bill that came over from the Senate). And he’ll ask anyone for help, conservatives as well as do-gooders, in an era when fewer and fewer legislators are crossing party and philosophical boundaries. He’ll also go straight to the top. Hinojosa was the sponsor of the open meetings reform bill, which was stalled in the House. He successfully lobbied Speaker Gib Lewis about the merits of the bill, then whipped out a press release to announce Gib’s blessing. Lo, hearts softened, and it became another piece of legislation for the governor’s signature.

But he’s not afraid to oppose the powers that be. He spoke eloquently against the referendum to ban a state income tax, saying it was an abdication of legislative duty. And Hinojosa votes his conscience even when it wins him few friends back home—take his votes against the lottery and the abortion bills.

Year in and year out Hinojosa is regarded as a sort of moral compass. When colleagues want to know the opinion of a member whose judgment is based on his beliefs, not on the last lobbyist he spoke to, they know they can ask Juan Hinojosa.

Jim Parker, 42, Democrat, Comanche

A country lawyer with a jeweler’s eye. Devoted his session to scrutinizing such legislative valuables as the governor’s crime package; in his care, diamonds in the rough became gems.

Because he labors far from the spotlight in glamourless committees (Criminal Jurisprudence and Judicial Affairs), Parker is the kind of legislator who is easily overlooked. But no one in the House did as much to clean up so many bills. As head of the subcommittee on the much-ballyhooed but poorly drafted crime package, he performed the near-impossible feat of making it palatable to both conservatives and liberals; for one of the few times in memory, neither side demagogued anticrime bills on the floor. As the head of another subcommittee on bail bond reform, he produced a bill that the full committee passed without a dissenting vote (“Nothing like that has ever come out of CrimJur eight to zip,” marveled a lobbyist). Later, when the Senate tried a last-minute ploy to undo the reforms. Parker held firm and the Senate capitulated.

In an arena in which egos frequently outweigh talent, Parker is just the opposite. Approached about carrying the bail bond bill, he said apologetically, “I’m no Bill Messer”—a reference to a master bill passer of yore. In fact, his relaxed wit and West Texas drawl make him an effective advocate when he does engage in floor debate. But he’d rather be in committee, guarding the law and the constitution.

Richard Smith, 49, Republican, Bryan

A superstar in the making. Just a sophomore, he already excels at every phase of the legislative game. Take one look at Smith on the floor as he walks from huddle to huddle, chewing on an unlit cigar, and you can sense that he understands exactly how politics works.

A case in point: Smith was a key player in one of the most crucial—and most dramatic—moments of the session. It occurred in the House Appropriations Committee, where Smith, who represents Aggieland, was a vocal supporter of additional funding for higher education. The committee had already voted down several proposals when, unexpectedly, Republican archconservative Bill Ceverha of Richardson switched sides and cast the decisive vote for adding $635 million more. When several of Bill Clements’ operatives pulled Ceverha into a back room to pressure him into reconsidering, Smith left the committee table and went to Ceverha’s rescue. “Wait a minute,” he said, flinging himself on the grenade. “Don’t beat up on him. I voted for more money than he did. If you’re looking for somebody to beat up on, beat up on me.” Ceverha held firm.

The mysterious tides of the House are no puzzle for Smith; he knows intuitively when to talk and when to keep quiet. Though a member of the insurgent Appropriations Committee octet known as the Pit Bulls, he didn’t antagonize committee veterans as most of his comrades did. Instead, he played good cop, offering compromise positions and soothing ruffled feelings. In the hectic final days of the session, he always seemed to be at the microphone during floor debate, yet he never wore out his welcome as he added an amendment here, asked a penetrating question there, and kept close watch on any bill involving cities (he is a former mayor of Bryan).

In a House where timidity seems to be contagious, Smith doesn’t shrink from a fight. When Republican hard-liners tried to send the appropriations bill back to committee, he asked tough questions that exposed the maneuver as a GOP grandstand play. Smith is never motivated solely by partisanship—or, for that matter, ambition. He is never devious or petty. It is a pleasure to find a gifted member of the House whose virtues are not weighted down by vices.

Terral Smith, 41, Republican, Austin

Universally liked and respected; a nice guy who finished first. He’s the House analog to Senator Ray Farabee—fair almost to a fault, someone who would rather compromise than win by running over people.

At the start of the session, Speaker Lewis made the inspired decision to depose the longtime chairman of the Natural Resources Committee, Tom Craddick of Midland, and install Smith in his place. Smith made Lewis look good by becoming the best chairman in the House. Craddick had ignored environmental groups; Smith brought them into the process. Soon he had both the Sierra Club and the Texas Chemical Council singing his praises—the equivalent of making peace between the gingham dog and the calico cat. With Smith’s guidance, the committee passed needed legislation that Craddick would have sent to Siberia, including assurance of clean water for colonias in South Texas.

Smith is one of those rare members whose mere presence invests a cause with credibility. When he saw a colleague run into trouble while trying to pass a bill involving theft of services, he went to the microphone and rescued him. Smith’s announcement that he would defend the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee’s revision of the governor’s crime package forestalled a feared right-wing attack; it breezed through floor debate.

Smith’s few failures were no less impressive than his successes. When Bill Clements reversed his stance against new taxes in mid-May, Smith and Barry Connelly of Houston rounded up a dozen Republicans and went to the governor to offer their support for his new position. Nice try, no cigar—Clements reversed himself again. But the group Smith forged remains together, poised to play a central role in the special session. His other disappointment was the defeat of his own bill regulating underground water. Smith nursed the bill further than anyone thought possible, only to lose a floor fight late in the session. As the clock approached midnight on the last day to pass bills, Smith thought he might have turned around enough votes to win passage. Should he precipitate a lengthy floor fight on the long shot that the bill might pass, or give up on his own bill so that other members could have time to pass theirs? Characteristically, he chose the latter—the kind of decision that has earned him the respect necessary to get the bill as far as he did.

Jack Vowell, 60, Republican, El Paso

The conscience of the Republican party and, for that matter, the entire House. A Horatius at the Human Services bridge who held off armies of Republicans and conservative Democrats bent on laying waste to welfare programs.

The biggest attack came in the House Appropriations Committee on a day when conservatives on the committee were in a feeding frenzy. Vowell, who had drawn up the Human Services budget, stayed on his feet for the better part of the day, patiently explaining every number in a soft, calm voice, providing the answer for every inquiry. He fended off a possible reduction in Aid to Families with Dependent Children by showing that AFDC cuts would cost the state $200 million in federal Medicaid funds. Welfare critics questioned whether the increase in requests for state assistance was the result of bureaucratic empire building: Vowell tied the increase to the downturn in the oil economy. He forestalled any attempt to cut family planning funds by showing that unwanted children made future demands on the welfare and prison systems. When the long battle was over and Vowell had staved off most of the cuts, he left the committee room shaken. “I thought he was just going to boo-hoo,” says a lobbyist.

Modest and unassuming, Vowell looks more like a neighborhood grocer than a successful politician. Yet he is second to no one on the Best list in importance. A rock-ribbed conservative on business issues, Vowell keeps Human Services from becoming a partisan fight. He beat fellow Republicans who waged a floor fight against a study on teenage pregnancy; he refuted Bill Clements when the governor asserted that AFDC caseload estimates were inflated by bureaucrats. He has taken the debate over welfare in Texas where it has never been before—out of the realm of rhetoric, into the realm of fact.

The Worst

Betty Denton, 41, Democrat, Waco

A lifetime nonachiever. Her role in the legislative process is to make life more difficult for the people who have to get things done.

As a member of the House Appropriations Committee, Denton had the responsibility for coming up with a budget for the treasury department. She wasn’t up to it. The problem, apparently, was that she couldn’t bring herself to cut the budget of a powerful statewide Democratic official, state treasurer Ann Richards—even though Richards herself had suggested a way to save tax dollars.

In Appropriations Denton played catch-up more than the Houston Oilers. “Wait! Wait!” she’d say. “What did they just do?” In one memorable exchange, the chairman explained that a motion had failed because it needed a two-thirds vote. Denton’s follow-up: “I have a question. Does it take a two-thirds vote?”

On second thought, maybe she was better when she wasn’t participating. When she did join in, the committee was treated to proposals like her rider prohibiting the Teacher Retirement System from making real estate investments outside of Texas. Republican watchdog Bill Ceverha pointed out that it was probably unconstitutional to tell managers where to invest. Denton: “It may well be, but I see no point in thirty-eight million dollars going to California.” Ceverha: “Even if they get a better rate of return?”

A stalwart TRS supporter over the years, Denton found herself in a session in which every budget-balancing plan (except, presumably, hers) called for the state to reduce its contribution to the system. Denton resisted all the way; then, after others had taken the lead in negotiating a compromise, she insisted on being the lead sponsor of the bill and presenting it on the floor. Otherwise, she fumed, she would stir up retired teachers against the bill. She got her way. “If pride of authorship goes before a fall,” grumbled a House insider, “Betty had better carry a parachute.”

Ted Lyon, 39, Democrat, Rockwall

Remember the most unpopular kid on the playground, the one who bullied all the others and then complained that nobody ever gave him any candy? That’s Senator Ted Lyon in a nutshell. When he isn’t threatening, he’s whining.

“He’s not someone who wants to work out differences,” said one lobbyist. “His first tactic is to intimidate.” When a conference committee was working on communicable diseases, Lyon demanded that his own controversial AIDS bill (it required doctors and hospitals to report positive AIDS tests to police and firemen on request) be made part of the package—or he’d kill the bill with a filibuster. The threat was unnecessary; a compromise was quickly worked out. When his bill to require motorcyclists to wear helmets ran into trouble in the House, Lyon again resorted to brow-beating. He summoned lobbyists with no connection to the helmet bill and gave them lists of members to lobby on behalf of his bill. The threat—you help me, or I’ll hurt you—was unspoken but unmistakable.

His legislative package was full of demagoguery, including an abortion bill that turned out to be almost wholly symbolic and an anticrime bill that was so bad (authorizing search warrants by telephone) that the law-and-order House didn’t pass it. He passed his abortion bill, but only after being rebuked by colleagues in committee for berating a pro-choice witness.

Lyon had more complaints than a hypochondriac. Gritch, whine, moan: Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby was stalling the abortion bill … Colleagues had failed to put him on the Torts Conference Committee … It’s so hard for a Democrat to get elected in his northeast Texas district (“When you talk to him about a bill, you don’t tell him that it’s good for Texas,” said one lobbyist. “You tell him that it’s good for him politically”). Maybe it’s harder for some Democrats to get elected than for others.

Jim McWilliams, 49, Democrat, Hallsville

Somebody help that man. His self-destruct button is stuck.

McWilliams’ involvement with AIDS-related legislation grew into a fevered obsession. Its symptoms:

––Grandstanding. McWilliams attempted to load AIDS-related amendments onto any legislative vessel that sailed by, even a bill defining rape of a spouse. On one occasion, the sponsor of a blood-bank bill agreed to accept McWilliams’ amendments—a routine process customarily accomplished with the stroke of the gavel. Not this time. McWilliams wanted to argue for his proposals. On and on he droned, one amendment after the other, purely for show.

–Ignorance. McWilliams and Mike McKinney of Centerville, the House’s only M.D., debated more than Lincoln and Douglas. McKinney kept pointing out medical booby traps in McWilliams’ amendments (one example: An amendment to require that positive AIDS tests be reported to the state health department was written in such a way that blood tests for all communicable diseases had to be reported).

–Hypocrisy. You might think that McWilliams, as a member of the Appropriations Committee, would do everything in his power to fund programs that combat AIDS. You’d be wrong. Instead, he did everything in his power to dismantle them. Why? McWilliams, it turned out, was on a vendetta against the state health department, which he accused of using “misleading educational terms and misleading figures,” though he failed to substantiate his charges.

–Tastelessness. McWilliams told a dumbstruck conference committee in open session, “I know the health department doesn’t do its job, because ten years ago I had gonorrhea, and nobody talked to my wife.”

All this might be amusing if AIDS were not such a terrible problem. Issues like testing needed to be addressed seriously, but McWilliams couldn’t do it himself, and worse, he preempted anyone who might have tried.

Meanwhile, he was spreading harm elsewhere. He tried to cut the agriculture department’s budget after Commissioner Jim Hightower canceled his appearance at a McWilliams fundraiser. His uninformed attack on the Human Services budget led a colleague to observe, “He acts like he’s morally offended by people being poor.” Remember the line from The Godfather: “It’s nothing personal. It’s strictly business”? With McWilliams, there is no difference.

Bob Melton, 43, Democrat, Gatesville

The Legislature’s answer to United Way: he’s always appealing for money. Lobbyists scatter when they see Melton approaching, because they know what’s coming. “He’s real basic,” said one. “He says, ‘You help me, I’ll help you.’” Said another, “He talks about money all the time.”

Melton is not the only legislator preoccupied with fattening his campaign treasury. But he is among the least discreet. “He leans on the lobby real hard,” says a victim. “He lets you know that he’s making a list and checking it twice.”

There are two rules about money in the Legislature. One is that you don’t solicit during the session. That’s a state law, designed to prevent bribes (by lobbyists) and shakedowns (by members). But the law applies only to individuals, not to groups. That loophole was all Melton needed to approach a tort reform lobbyist on behalf of the House Democratic caucus and say, “The trial lawyers [opponents of tort reform] have contributed, and you need to get in it.” The second rule is never mention money and issues in the same conversation. Melton insists he doesn’t. But a lobbyist remembers Melton asking, “Here’s where I can go with you. Is that enough to get help?”

If there is an excuse for Melton, it is self-defense. He is a maverick in a body where conformity is overvalued. He doesn’t kowtow to the lobby or the Speaker, and his independence has earned him well-financed campaign opponents. His reaction, however, has been to have contempt for the process, and not just where money is concerned. After winning a prolonged floor fight over his bill to provide counseling to prison inmates convicted of sex crimes, he didn’t offer the usual thanks. Instead, Melton told the House, “Welcome to the twentieth century.” As members booed and raced to the microphone to overturn the vote, Melton apologized, saving his bill—but not his reputation.

Pete Patterson, 52, Democrat, Brookston

The living proof of the adage that the Texas Capitol is built for giants but inhabited by pygmies. In the great march of time he plods along at the rear, decades behind, intellectually wrapped in the folds of the crocheted Confederate flag that dominates a wall of his Capitol office.

His legislative program was designed primarily to codify his prejudices as law. Nothing came close to matching his celebrated bill in 1985 to prohibit foreigners from owning land in Texas, but you’ve got to give the guy credit for trying. This year’s targets: illegal aliens, foreign oil, federal judges, and anyone who speaks Spanish. The last group was addressed in his proposed constitutional amendment to establish English as the official language of Texas. Patterson’s oratorical style can best be described as an inarticulate monotone; even native English speakers can have a hard time understanding what he’s talking about. Once he kept saying “repars” instead of “repairs” during a debate on the House floor. “Hah,” grunted a colleague standing nearby. “He wants to make English the official language, and he can’t even speak it.” Sometimes Patterson is not so great at understanding it, either. “He’s impossible to work with,” said one lobbyist. “I tried to explain a simple bill to him, but he just didn’t get it.”

Fortunately Patterson is ineffective (none of his controversial bills made it to the floor). But he’s not insignificant. He is the archetypal member of what might be termed the Ostrich caucus—a bipartisan group of legislators who think that all of Texas’ problems would be solved if the rest of the world would just go away and leave us alone. But it won’t. Maybe Pete will.

Al Price, 47, Democrat, Beaumont

For Al Price, all matters are black and white. He is the ultimate one-issue legislator: almost every subject is about race.

Take his role as a member of the Insurance Committee. Price accomplished what had been previously thought to be impossible—he made you feel sorry for insurance executives. At one hearing on insurance taxation law, Price asked the white male who had just testified, “Are you the only representative from your company [here today]?” The answer was yes, to which Price responded, “I’m sorry, because I would like to get a better impression of your company.” He then requested that the man, and subsequent male witnesses, bring black and female executives with them next time they come to testify.

At another hearing, one unfortunate witness during his testimony made the mistake of using the industry jargon for companies that meet state regulation requirements—“white list.” Price, in real life a pilot for American Airlines, used the phrase as a runway to take off on a diatribe on race.

The sad part is that Price’s concerns are legitimate and he is an intelligent, articulate legislator who could actually use his gifts to advance the issue most important to him. Instead, through small-mindedness and hectoring, he has squandered his potential influence. When he spoke during floor debate against authorizing private prisons—he argued eloquently that only the state should have the power to take away someone’s freedom—no one was paying attention.

And it was Price who suffered one of the most humiliating moments of the session. There is a forum for House members to address serious, individual matters, known as a personal privilege speech. It’s an option that’s rarely exercised. Price used it to ask his colleagues to table a bill introduced by another Beaumont legislator that would create a hazardous-waste research center at Lamar University, located in Price’s district. Price, who has been feuding with the university for years over its minority hiring practices, didn’t oppose the substance of the bill; he was miffed that someone else was carrying a bill affecting his district. As an indication of the esteem in which Price is held, fellow Black caucus member Ron Wilson rose to demolish Price’s claim that the legislation was local in nature. Price’s motion got 14 votes in the 150-member House.

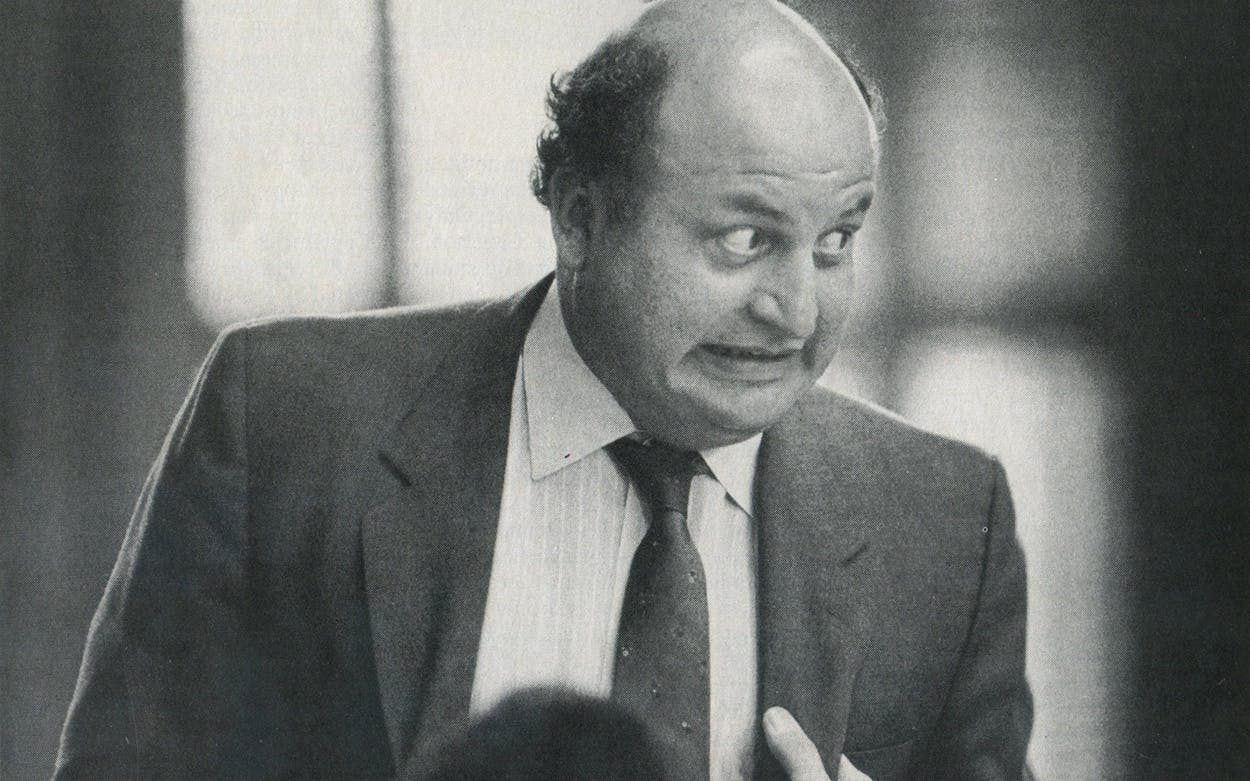

Craig Washington, 45, Democrat, Houston

All session long the word from the Senate was “Craig is doing better.” Everyone, including us, rejoiced in the news. Had Washington, in his third Senate session, finally regained the form that had made him one of the great House members of all time? Alas, alas, the answer was no. As the session drew to a close, Washington committed the two most egregious blunders of the entire 140 days. He hurled unwarranted accusations of racism at Speaker Gib Lewis and forced an utterly pointless special session on tort reform.

Washington unleashed his fury at Lewis after the House killed a Senate amendment requiring the new Texas Department of Commerce to award 10 percent of its contracts to businesses controlled by minorities and women. His outburst (“He’s standing in the door like George Wallace….He’s a chauvinist racist in my view”) was bad politics: It poisoned Washington’s chances of getting what he wanted from the House, then or later. It was also bad policy. Whatever their merits, minority set-asides offer notorious opportunities for tokenism, pork barrel, and corruption. To equate opposing them with opposing school integration is irresponsible.

So was his twenty-minute filibuster to kill the tort reform compromise as time ran out on the session. Washington argued that there had been no chance to study the agreement that had been hammered out just hours earlier. On the face of it, he had a point. But there had been plenty of time to sit in during the week of negotiations (as other senators, but not Washington, had done), and there was still plenty of time to get an explanation from his colleagues (which they were eager to give him). In short, Washington was unprepared and conceded as much. He filibustered anyway. In the special session that began the next day, Washington asked questions for around six hours. Most of them concerned points that had been settled in the bill that had been debated and passed by the Senate three weeks earlier. The rumbling on the Senate floor was that Washington was trying to justify his filibuster. One day later, the compromise passed unchallenged.

And so Washington is on the Worst list for the second session in a row. It’s too bad. No one who heard his speech opposing Bill Clements’ appointees to the Board of Pardons and Paroles (Clements replaced two minority board members with two white males) could doubt Washington’s ability: “I hope to live long enough to see a day when the color of an individual’s skin no longer matters. I do not delude myself into believing that that day has arrived.” The Senate, swayed by his eloquence, voted down the appointments. When Washington’s on, he’s the best. But when he’s off, he’s the worst.

Triple Whammy

Yes, in case you’re counting, we have only seven names on the Worst list instead of the usual ten. We have left three places vacant in symbolic recognition that the most significant failures of the session belonged to the three leaders: Bill Clements, Bill Hobby, and Gib Lewis. Under our rules, the leadership is ineligible for either the Best or the Worst list. The governor and the lieutenant governor, after all, aren’t legislators, and the Speaker rarely functions as one. But if they were eligible, there’s no doubt where they would be. Individually, each of the three leaders had his defenders around the Capitol; collectively, they had none.

Bill Clements, 70, Republican, Dallas

He’s not the first politician to paint himself into a corner, but he’s surely the first to survey the situation and then apply a second coat.

After campaigning on a platform of no new taxes, Clements consented in February to extending temporary sales and gasoline taxes passed last fall. When it became clear, however, that still more new revenue was needed for even a bare-bones budget, Clements reinstituted his opposition to any other new taxes, like a deflowered virgin seeking to redefine chastity.

Clements kept insisting that it was possible to maintain state services without more taxes. His budget showed how it could be done—with cuts in corpulent programs like vocational education and full-day kindergarten, and new revenue from selling state lands and making Texas A&M and the University of Texas use their endowments for research. All of his proposals had some merit; all were highly controversial. The only way they could become reality was for Clements to throw all his weight behind them, as Ronald Reagan did with his budget in 1981. But Clements didn’t even lobby for his budget-balancing proposals. Without his support, they quickly died. The only choices he left the Legislature were to make deep cuts or send him a tax bill he had sworn to veto, and they weren’t eager to do either.

Then came the unfathomable events of late April and early May. Clements went on a seventeen-city tour to build support for his no-new-taxes stance. Having built it, he promptly tore it down. After a meeting with H. Ross Perot, Clements hinted that he was ready to reverse himself and agree to raise taxes. But the next day, after meeting with angry House Republicans, he reversed his putative reversal. He spent the rest of the session feuding openly with Bill Hobby and vowing to stick by his veto pledge even if state government had to shut down in September. Meanness and stubbornness had become substitutes for leadership.

Bill Hobby, 55, Democrat, Houston

From the start, he was dispirited this session, almost as if he felt predestined to fail. The prophecy indeed proved to be self-fulfilling.

Throughout the session, Hobby acted like a reincarnation of Henry Clay, who is remembered for saying that he would rather be right than be president. Hobby is unquestionably right that the state should stop relying on oil and gas, overhaul its tax structure, and build its future on education. But he was wrong to insist on getting his way this session. Hobby didn’t hold the right cards; the aces belonged to Clements: 56 Republicans in the House, enough to sustain a veto. Hobby upped the stakes anyway. As president of the Senate and as its spiritual leader, he gave his blessing to a spending bill that required $3.1 billion in new taxes above Clements’ bottom line.

Hobby gambled that either Clements or the House Republicans would eventually see the light and come around to his way of thinking. He badly misjudged both. The size of the Senate bill was an affront to Clements, an indication that Hobby wasn’t making the slightest effort to compromise or even to take Clements seriously. As for the House Republicans, a handful might have voted to override Clements’ veto of a compromise budget package; an override at the spending and taxing levels Hobby sought was unthinkable. By May the Hobby-Clements relationship was a textbook disaster, complete with private and public insults. They were two stubborn men, each determined not to yield.

Bill Hobby has been a great lieutenant governor. But he wasn’t a great lieutenant governor this session. He forgot the most basic rule of politics. It appeared on lapel buttons during the last week of the session, and it was the theme music for the slide show the Senate staff presented on the final night: “You Can’t Always Get What You Want.”

Gib Lewis, 50, Democrat, Fort Worth

Where was the Speaker in this battle of the titans? Nowhere. For most of the session, Lewis never had a plan to deal with the budget. Then, when there was too little time left to accomplish anything, Lewis burst forth with a series of plans du jour, none of which anyone took seriously, including Lewis. On the day that a state lottery bill came up for a vote in the House, Lewis announced simultaneously that (a) the lottery was part of his latest package to solve the crisis and (b) he wasn’t going to ask anyone to vote for it. With that ringing endorsement, the lottery went down to defeat, and a new plan surfaced.

With Clements and Hobby at loggerheads, the good-natured, well-meaning Lewis should have been the peacemaker and deal maker. But he was paralyzed by the deep divisions within the House and his own lack of vision for Texas. Lewis prefers to have others work deals out and bring them to him for enforcement—an approach that worked for tort reform and trucking deregulation but not for the budget.

All session long the House kept sending mixed signals. It quickly passed a tax bill—making the temporary taxes permanent—that the governor said he would accept, but the language was deliberately written to prevent the bill from becoming a vehicle for a later compromise. Score one for Clements. Lewis kept assuring the Senate that another tax bill was on the way. Score one for Hobby. But it never came. Meanwhile, the House Appropriations Committee was floundering. It didn’t know how much money to spend, because Lewis didn’t know how much he wanted to raise. Without guidance from the Speaker’s office, House spending rose so high that in budget negotiations with the Senate, the House disavowed its own bill.

In effect, Lewis had let the House vote to spend high and tax low, as every politician the world over would like to do. But sometimes politics requires hard choices. Making them isn’t fun, and it isn’t easy, and it gets people beat. But making these choices is what makes leaders, and that’s what the House of Representatives—and, for that matter, the 70th Legislature—didn’t have.

Most Moving Speech

The usually inattentive House fell silent when Ernestine Glossbrenner (Democrat, Alice) made a rare trip to the microphone to oppose the abortion bill: “I’m a fat old-maid schoolteacher. I’ve never been pregnant, and I’m never going to be pregnant. But I have a concern here for those who will…I believe what we’re doing here today will mean that some of the abortions that are being performed in clinical places now will be performed in back alleys and dirty motels. And some young girls when they are old enough to be mothers will have been, if not killed, probably disfigured…”

Best Testimony as a Lobbyist

Bob Leach of Noonday, president of the Texas chapter of the United Game Fowl Breeders Association, in opposition to a bill that would mandate seizure of cockfighting equipment: “If God Almighty Himself wanted to try to create earth today, he couldn’t get a permit to do it.”

Roger Smith Booby Prize

To Randy Pennington (Republican, Houston). Named for the chief executive officer of General Motors, the award is given to the legislator who displays the most displeasure with H. Ross Perot’s involvement in state government. After Perot had persuaded Bill Clements to soften his stance against new taxes, Pennington stormed into the governor’s office, insisted that Clements reconsider, and said, “I’m tired of Ross Perot running Texas. GM gave him eight hundred million dollars to leave the company. Let’s give him a billion to leave Texas.”

The Bermuda Triangle

Three of the Legislature’s brightest members are missing from the Ten Best list this year. They plotted a course to solve the state’s fiscal crisis but discovered, too late, that their heading took them into a legislative Bermuda Triangle, from which there was no hope of accomplishment or escape.

Mike Toomey (Republican, Houston), the brilliant budget cutter of 1985, helped devise Bill Clements’ strategy to hold the line against new taxes without reducing services. The Toomey plan depended upon finding ingenious ways to raise money without raising taxes. Unfortunately, the things he came up with (such as raiding educational trust funds) butchered cows more sacred than any bovine in India. The Legislature didn’t give them serious consideration, and neither did Toomey. His reputation as a budget cutter was tarnished when he failed to propose a single spending reduction during House debate on the appropriations bill. Instead, he tried to pass the buck with a motion to send the bill back to committee. It was soundly defeated. For all his mastery of numbers, Toomey still hasn’t figured out how to change one of the basic assumptions of legislators—that programs with large, vocal constituencies are off-limits to the knife.

Rick Williamson (Democrat, Weatherford) was the catalyst for the formation of the Pit Bulls, a group of eight sophomores on the House Appropriations Committee who challenged Chairman Jim Rudd’s business-as-usual approach to the budget. “Pit Bulls” referred both to their location on the lower tier of seats in the committee room and to their tenacious hounding of witnesses from state agencies and colleges. Perhaps the hardest-working member of the Legislature, Williamson envisioned himself as another Toomey, but while he had Toomey’s drive to ferret out waste, he lacked grace and sometimes facts. He quickly alienated the Capitol establishment with his hostile attitude toward the big boys (UT, A&M, the Highway Department); they call him Nitro. Williamson was the dominant figure of the session while the budget remained in committee, but when the Pit Bulls brought their ideas about financial accountability to the floor, they found that they had no following. Williamson’s reputation had preceded him: he was brainy but erratic. Soon the Pit Bulls were renamed the Pit Puppies.

When the Pit Bulls faltered, they turned to Stan Schlueter (Democrat, Killeen), the House expert on taxes and a Machiavelli in boots. In hush-hush meetings in Schlueter’s office, they developed a compromise budget and tax plan that offered a realistic solution to the crisis. It called for a modest sales tax increase (and provided Bill Clements with a face-saving way to accept it), while funding state agencies adequately but not generously. Some of Schlueter’s own pet legislation found its way into the package, including a ban on income taxes. Schlueter was the only person in the Capitol who exercised any leadership on the only issue that really mattered, but he couldn’t sell Stan’s Plan, as it became known, to the Clements-Hobby-Lewis triumvirate. As the case always seems to be with Schlueter, his work will come to fruition after the regular session; he remains the best member of the Legislature never to make the Ten Best list.

Render Unto Pharaoh That Which Is Caesar’s Award

Speaking in favor of the abortion restriction bill, L.B. Kubiak (Democrat, Rockdale) perorated: “You know, in Roman days the gladiators used to get their men down, their opposition down, and they’d look up to Pharaoh, and they’d look for a signal—give ‘em life or give ‘em death.”

Best Nickame

Because of her insistence that lobbyists speak to her staff and not to her, Democrat Judith Zaffirini got dubbed the Junior Senator from Laredo. Her chief aide, naturally, was the Senior Senator from Laredo.

Please Don’t Tell Us About Your Private Life Award

When criticized for sponsoring a bill to create a new underground water district in order to keep a hazardous waste dump out of his county, Cliff Johnson (Democrat, Palestine) replied: “If they had pictures of me doing a homosexual act with a gorilla in a zoo, I’d still carry this bill.”

Furniture

The term “furniture” first came into use around the Legislature to describe members who, by virtue of their indifference or ineffectiveness, were indistinguishable from their desks, chairs, and spittoons. It is now used casually and more generally to identify the most inconsequential members. Here is the furniture list for the 70th Legislature:

New Furniture

Bill Arnold (Democrat, Grand Prairie)

Weldon Betts (Democrat, Houston)

A.R. Ovard (Republican, Dallas)

Glenn Repp (Republican, Duncanville)

Used Furniture

Roy Blake (Democrat, Nacogdoches)

Ben Campbell (Republican, Lewisville)

Eldon Edge (Democrat, Poth)

Ron Givens (Republican, Lubbock)

John Leedom (Republican, Dallas)

Gregory Luna (Democrat, San Antonio)

Roman Martinez (Democrat, Houston)

Irma Rangel (Democrat, Kingsville)

Randall Riley (Republican, Round Rock)

Garfield Thompson (Democrat, Fort Worth)

Antique Furniture

Charles Finnell (Democrat, Holliday)

Charge of the Light Brigade Award

Two days after the House had voted for a constitutional amendment banning income taxes, Senfronia Thompson (Democrat, Houston) asked the House for permission to introduce a bill authorizing an income tax. The normally routine motion was voted down.

Dishonorable Mention

Bob Leonard (Republican, Fort Worth). He carried one of the session’s worst bills in one of the session’s worst ways. The bill exempted nonprofit-religious-group affiliates from financial disclosure requirements. Among the organizations exempted were nonprofit hospitals, some of which (such as Houston’s Methodist Hospital) have come under heavy fire because of press investigations of just the sort of records that the bill would have made unavailable. Getting into the spirit of the bill, Leonard practiced a bit of nondisclosure himself: He neglected to tell colleagues working on the bill that he had a special interest in it (he’s on the board of directors of a hospital holding company whose records would be closed by the bill).

The bill had passed the Senate and was on the verge of passing the House when those nasty reporters struck again. The Houston Chronicle and the Dallas Morning News revealed what the bill did and what Leonard’s interest was. Just as the bill came up for a vote, Steve Wolens of Dallas raised a point of order against further consideration. Speaker Lewis upheld the maneuver, killing the bill, but he neglected to cite which rule had been violated. “What rule?” someone shouted. Wolens shouted back: “The bad bill rule.”

Best Insights

Foster Whaley (Democrat, Pampa), during a long and frustrating Appropriations Committee conference, observed: “We got too many people on this committee, and I might be one of them.”

Gwyn Clarkston Shea (Republican, Irving) made this attempt to send an Insurance Committee bill to the full House for approval: “I move that a … Mr. Patrick’s House Bill 523 be reported back to the a … Wait, wait, wait. Make a motion that House Bill 523 pass and recommend … I don’t know what I want to do.”

Most Improved

How did the session go for Ron Wilson (Democrat, Houston)? There was a little bit of everything: enough good to make him a contender for the Ten Best list, enough bad to remind us that he made the Ten Worst list in 1985, and enough in between to keep him from winding up in either category.

Wilson’s foremost contribution was to restore the reputation and independence of the Liquor Regulation Committee, of which he was the chairman. Two years ago the joke circulated through the Capitol that Wilson’s predecessor as chairman had lost the ability to walk, so much time did he spend being squired about in the liquor lobby’s fabled van. Wilson chased the money changers out of the temple and took the committee away from the lobby. He even passed the law that bans drinking while driving.

Last session Wilson used his mastery of rules to play self-indulgent games. This time he used the rules the way they’re meant to be used—sparingly but lethally. The AT&T deregulation bill was greased to slide through the House when Wilson threw a parliamentary pile of sand on it, causing the final, fatal delay that forced AT&T to swallow a distasteful compromise.

On the downside, Wilson lost three bills on the floor. His constitutional amendment establishing a state lottery went down to a surprising early defeat, but he may get a chance to change that result during the upcoming special session. He lost control of his bill to chastise Houston’s metropolitan transportation authority when the floor debate turned into a free-for-all, but he did change that result when a later version came up for a vote. The really bad news was Wilson’s bill allowing Texans to carry concealed weapons. Last session the bill’s sponsor made headlines by saying, “Every black man in Houston carries a gun.” So why was Ron Wilson carrying this bill? It’s all right to play games, but not with loaded weapons.

- More About:

- Best and Worst Legislators

- Texas Legislature