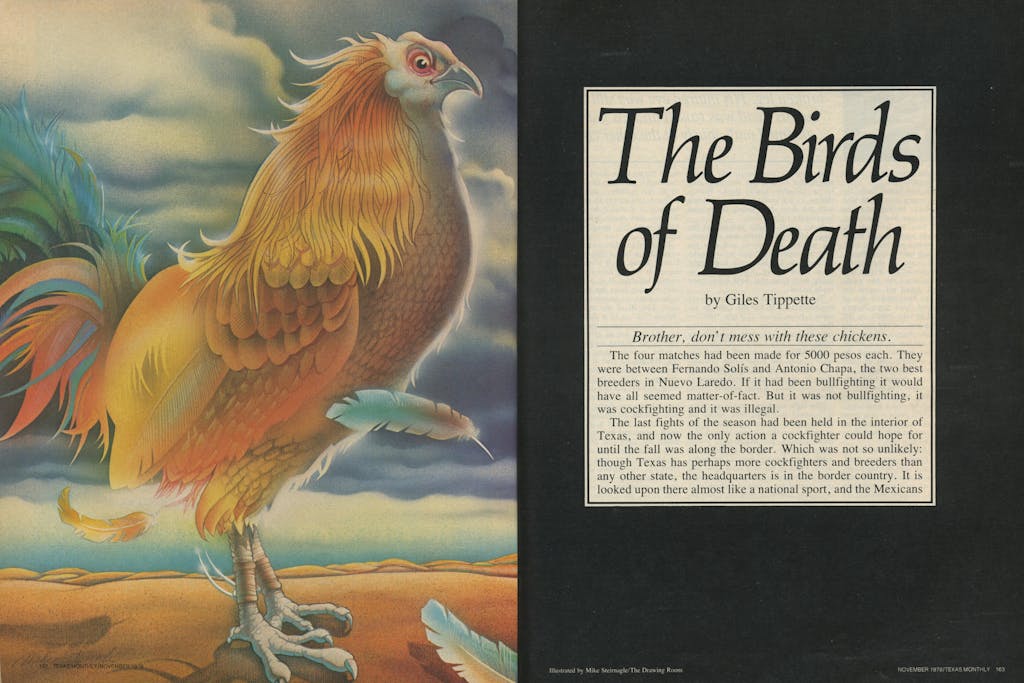

The four matches had been made for 5000 pesos each. They were between Fernando Solis and Antonio Chapa, the two best breeders in Nuevo Laredo. If it had been bullfighting it would have all seemed matter-of-fact. But it was not bullfighting, it was cockfighting and it was illegal.

The last fights of the season had been held in the interior of Texas, and now the only action a cockfighter could hope for until the fall was along the border. Which was not so unlikely: though Texas has perhaps more cockfighters and breeders than any other state, the headquarters is in the border country. It is looked upon there almost like a national sport, and the Mexicans and Texans fight their birds freely across the Rio Grande.

But the match had begun badly for “Nano” Solis, a young man of 28 who looks enough like a bullfighter to be one, with his slim size and handsome, sculptured dark face, his jet-black hair and flashing white teeth. It had begun badly because he had put his best bird, a purebred Spanish cock named Pepito, in the match in hopes of shaking his opponent’s confidence. But Pepito was in trouble. Three times the two cocks had been pitted, faced off across the line drawn in the hard-packed dirt of the little ring, and three times Nano’s handler had had to take Pepito up lest the referee call a win for the opposing cock. Now Pepito had a broken left leg and his right eye was swollen almost shut. The handler walked around the ring with him, cradling him in both arms, taking mouthfuls of water and spraying them down Pepito’s back, trying to cool him, to give him new life.

Outside the ring Nano looked worried. Even though he was a professional cockfighter, 5000 pesos was a great deal for a man of his poor means to bet on each match, and he had counted on Pepito winning this first one.

And it would be a hard thing indeed to lose Pepito. Pepito’s sire was dead, killed in a fight at one of the big ferias (fairs), and Pepito was the last of the pure Spanish stock he’d imported from Spain. Watching, he now regretted his decision to fight the little red cock, but there was bad feeling between him and the opposing breeder, Antonio Chapa, and he had wanted to embarrass him quickly.

But Chapa had countered with a pinto cock, a brown-and-white-speckled cock of mixed German and Spanish breeding that was jumping higher than Pepito and spurring him about the head. The pinto was, as some boxers are, a headhunter. He had several times dazed Pepito and had closed one eye. They were not fighting the cocks with the long, deadly steel gaffs that are attached to the natural spurs of the birds, nor with the swordlike inch-and-a-half slashers, but with short, blunted steel spurs. It was late in the season and neither breeder had wanted to risk losing valuable battle stock. Nevertheless, a cock could be beaten to death with the short spurs unless the referee stopped the fight in time.

Now, as his handler still circled the ring with Pepito, Nano was considering whether to concede and save his cock or hope that Pepito would make a comeback. The little cock had fought three times before, but he’d won so easily each time that he’d never been really tested.

The crowd and the referee were beginning to yell for the fight to resume. “¡Pelea, pelea!”—“Fight, fight!”—they were shouting. And the referee was motioning to both handlers to bring their cocks forward. Chapa, who was handling his own cock, came forward readily, but Nano’s man pretended not to have seen. He glanced over at Nano to see what the owner wanted to do, and Nano stared blankly back, thinking.

The fight was being held in an arena, if it could be called that, about ten miles outside Nuevo Laredo. It was reached from the highway over a dirt obstacle course that should have ruined every car that came there. The arena itself was nothing but a tin-roofed shack, open on all four sides. The ring was an enclosure twenty feet in diameter formed by a three-foot-high wall of canvas. Forty or fifty spectators sat just behind the canvas wall in old and rusted metal folding chairs, most of which were imprinted, from some long past time, with ads for Coca-Cola or Carta Blanca or Corona. Nearby, in a booth, a woman cooked carne asada and fajitas over an open fire, and those at the ring could smell the mesquite smoke and aroma of the meat. The impresario of the establishment, Miguel Martinez, sold soda pop and beer and Scotch whisky from his own booth. He was doing a lively business during the delay, though not so much on the Scotch because it cost 30 pesos (about $1.50 American), and, besides, as one spectator told his friend, it was too hot to drink whisky anyway. In the vicinity of the pit there stood a whitewashed ramshackle building that was referred to as the “rancho,” and a couple of stripped, rusting trucks sat in the yard, looking as if they’d be there forever. Beyond that there was nothing but baked soil, dry mesquite trees, and chaparral.

Contrary to what most people think, cockfighting is not illegal in all of the United States. It is illegal in Mexico, except at the big fairs that are held on certain holidays. It is permitted at the fairs because there the government can collect a tax, or impuesto. Miguel Martinez, like all of the operators of the “brush pits,” is in a difficult position. Since his business is illegal, he cannot pay the tax, but to exist he must pay the tax. So, instead, he pays a mordida, a bribe, in order to be able to pay his tax. He doesn’t find it ironic or even unusual. Asked about it, he just shrugged, “Well, that is the way of the thing, so what can one do?”

Miguel had promoted this fight. It had taken some doing because it was so late in the season, but he knew that if he could arrange it, it would draw a good crowd and he’d make money. To attend the fight cost 50 pesos, quite a sum for an afternoon of entertainment in Mexico. And then there was the food and the drinks. Miguel had already made his money and he didn’t much care how the matches turned out. As is the custom in Mexico, he put up no prize money. The winnings consisted of bets made by the owners on the cocks. And then there was the betting among the spectators, which was also a private affair. The betting on the match had generally been 100 pesos to 70 in favor of Pepito, and the customers who had bet on him were incensed at the showing he had made. They were beginning to shout curses and insults at the handlers, which was why Nano never handled his own gallos (cocks).

“They yell bad things,” he said, “especially if they are losing. Certain insults and curses that a man cannot well stand. Sometimes they get drunk and lose their heads and say too much. So I stay out of the ring because”—here he smiled slightly—“I have a little bit of a temper, and if the wrong thing is yelled at me it could be there would be more fights than just the one between the gallos.”

Nano has been raising and breeding fighting cocks for about ten years, but fighting them himself for only four. He says he began fighting them himself to better establish his reputation as a breeder. He presently has about two hundred battle cocks and battle stags (a cock under eighteen months), and he and his wife breed, train, and care for them. Of course not all two hundred of them are in fighting trim. During the regular season he will keep only about twenty gallos in training.

But now he had to make a decision, because the referee was growing angry, and that would not do. Also Chapa yelled across at him, with an insolent, triumphant look, “¡Pelea o pager!”— “Fight or pay!”

Chapa is ten years older than Nano. He is a fair-complexioned man with reddish hair. He has big shoulders and a bit of a potbelly. He handles his own cocks in the ring because he doesn’t care what the spectators shout. Sometimes he shouts insults back at them. He resents Nano because Nano has consistently beaten him.

He shouted at Nano again, and Pepito’s handler, still cradling the cock in his arms, looked over at the breeder.

Fernando stared back for a long moment, then slowly nodded.

“¡Arriba!” the referee yelled, motioning both handlers forward. The small crowd yelled as the cocks were faced across the line. The big pinto, held by Chapa, strained forward, bristling his hackles. But Pepito barely had to be held. He sagged sideways toward his broken leg. It was not broken at the thigh, but lower, so that the leg was more or less held together by the tough sinew and skin. His eye was still closed, but his head was raised and his good eye gleamed maliciously at the other cock. The referee dropped his arms and the two handlers stepped back. The two cocks leaped at each other. The pinto went higher, vaulting with his back almost parallel to the ground, hitting Pepito with quick one, two, threes, each time they went up. But Pepito was slugging back, going to the body just below the wing, hitting hard with his good right leg and using his broken left more for a guide and a hold. They went up and up and up. Five, ten times. At first the pinto, looking bigger but not heavier, was forcing Pepito back. But the little rooster hung on, socking away with that right leg. Gradually the pinto dropped back until they were even across the line again. Finally they both stopped, squatting on the ground, pecking futilely at each other. The referee made a sign to the handlers to take up their cocks, and Nano’s man rushed forward to pick up Pepito and do what he could to revive him. Outside the ring Fernando raised his eyes to the sky as if in prayerful thanks.

In cockfighting, on both sides of the border, the referee is an integral part of the fight. He is responsible for enforcing what few rules there are to the sport (primarily the weight matching), and his word is absolute law. He can, whenever he wishes, disqualify a cock, and bets are paid off on his decisions. He is especially important in fights that are not fought to the death, but to a decision, for the decision is his and his alone. Normally the handlers must instantly bring their birds to the line when he calls for them, but this referee, moving unobtrusively around the ring, was being especially lenient, for he knew that the two cocks had not had a sufficient training period and were tired and in poor condition.

Nano would, however, have to make another decision, though it seemed to him that Pepito had rallied somewhat and he was beginning to wonder if Chapa’s cock had as much heart as he might need. But the bettors did not seem worried. Those who had bet on the pinto were now seeking to press their bets with Pepito’s backers. There were few takers. In the break there was much laughing and going back and forth to the refreshment stands. Miguel Martinez seemed the most contented man there.

The Mexicans say that their cocks are far superior to those in the United States. American breeders clearly do not agree. A man we will call Morris, from a small Central Texas town, who, like his father before him, has been breeding and fighting cocks all his life, said: “Yeah, I’ve heard that old story and it makes me laugh. Tell you what, one time I took fifty chickens down to a big fair in Monterrey. Fought forty-seven times and won forty and that was against about as good as they got in Mexico. They say that because they got more foreign bloodlines than most of our cocks do, German and Spanish and Belgian. For some reason they think that makes them better.”

Morris is a big, ambling, slow-talking man of some forty-odd years who wrinkles his brow in concentration as he tries to explain about cockfighting. He looks more like a farmer than a cockfighter.

“There are some other differences, too,” he said. “We’ll fight cocks within a three-ounce limit of each other, but they’ll try to get them right on the nose and even squabble over half an ounce. Hell, I’ve give away as much as six ounces when I knew I had the best cock. Won with him, too.”

Morris keeps some sixty prime fighting cocks on his place, maintaining careful breeding records on the cocks and the hens and leg-marking them so that his breeding lines are exact. He does not cage his cocks as many breeders do but keeps them staked out in a large field. Each cock is leashed by one leg to a twelve-foot cord on a swivel. “That way,” he said, “they’ve got 450 square feet of movement and they’re exercising all the time. It also lets them get grasshoppers and bugs and other natural foods that are good for them.” Each cock has a tepeelike house with a high roost inside made of stacked-up rubber tires. To get on and off their roost requires some effort since roosters don’t fly too well. Mostly they have to jump, which is good for their leg muscles.

The similarity between fighting cocks and boxers is astounding, both in their training and in the ring. In the ring, the slugging, though with spurs rather than fists, is obvious. So is the repeated pitting, which is similar to the system of rounds and which echoes the old-time style of boxing when a man had to “come to taw” (return to a line at the center of the ring). Also, in the short-spur form of Mexican fighting, there is only occasionally a “knockout,” and most fights are ended on a decision by the referee.

But it is in the training that the resemblance is most striking. Cocks do roadwork just like boxers. Depending on what type of card he is preparing for, a six-, eight-, or ten-match fight, Nano will begin training that many cocks plus a few more in order to have the required number ready at the time. Two to three weeks prior to the fight, he starts them with three minutes of roadwork, running them around an improvised ring he has on his property. Each day he increases the roadwork up to a maximum of twenty minutes.

“After that much time,” he says, waving a hand, “you do not accomplish what you are after, which is the conditioning of the cock. All you are doing is tiring muscles that are ready to fight.”

The cocks’ legs are plucked up to their bellies, as are their posteriors. A straight line is also sheared down their backs for ventilation, since cocks get hot easily and lose strength by being overheated. During the training period, Nano rubs down the cock’s thigh with

a mixture of glycerin and alcohol. He says it makes the muscles more supple. Morris does this, too, though he uses a different mixture, which he says is a secret. But he does not run his cocks. Instead he goes out each evening, when they are on their roosts, and gives their leashes just enough of a tug to make them fight and struggle to stay on their perches.

“See, that develops their legs and wings and wind at the same time. I’ll give a half-dozen tugs on one leg then switch over to the other one. The good thing about this method is that it really makes them flap those wings and that develops breast muscle, which is important the way we fight in the U.S. with the gaffs. A cock will get hit in the head, but he’ll get hit in the breast a lot more, and you want as much meat between that steel and his vitals as you can get.

“Another thing, you don’t want any fat in the rear end. I’ll take a cock up and feel his behind and if I can feel his gizzard I know he’s in shape.”

To hold a fighting cock is a surprise. They are hard—hard like well-conditioned muscle—much harder than you’d ever expect a bird to feel.

“Oh, it’s muscle all right,” Morris said. “You can maybe fry a stag if he’s a young stag, but you get one of those three- or four-year-olds killed, all you can do with him is make chicken and dumplings. Always somebody around the pit ready to buy your dead birds for meat. They don’t go to waste.”

All breeders spar their cocks. They strap on the steel gaffs and on the end of each they stick, a small cork ball, much as you would with a foil or an epee. They are sparred to test them for gameness, endurance, and general quickness.

“Sparring,” Nano said, “is also very good for the conditioning. After all, the hardest work the gallo will do is in the ring, so the more fighting you can give him the better will be his condition. It is the same with boxers, is it not?”

Nano has cocks in a wide range of prices. They are somewhat cheaper in Mexico than in the United States, but they are still expensive as chickens go. His lowest-priced stags will cost a buyer at least $20, and those out of proven fighters will go up to $50 and even $100. He has a few cocks like Pepito that would cost $200 or more—if he were willing to sell them.

“You must not,” he said, “sell too much of your best breeding stock or else you are out of the breeding business.”

Of course the hens are sold, too. And some of these bring as large a price as the cocks.

“Most people do not understand,” Nano said, “that the gallina is more important to the breeding than the cock.

“I test my hens, sparring them against each other just as I do the gallos. But the true test of a hen is in the performance of the gallos she brings. That is always the test, in the ring.”

Morris’ run-of-the-mill cocks bring about $50. After that the prices start upward rather sharply, going to $150, $200, and $250. Not all his cocks are kept in the field. Eight or ten are housed in a special shed. These are the expensive cocks, the ones that have won time and time again and have been or are about to be retired to stud.

But in one special run is the true cock of the walk on Morris’ place. This is his cock that has fought eleven times and won every match. He is in a large, cool enclosure, surrounded by a little harem of hens. His fighting days are over.

“That cock,” Morris said firmly, “is not for sale at any price. I wouldn’t take two thousand dollars for that bird. Why should I? He’s only four years old and God knows how many chickens I’ll get out of him, the least of which will be worth a hundred dollars as stags. That cock is famous. Even if I wanted to fight him again I probably couldn’t make a match. No cockfighter is going to put his bird in against that one.”

The eleven-game winner does not have a name, nor do Morris’ other cocks.

“No use naming them. I just go by their color and their leg markings. Tell you a story about that eleven-game winner. My boy who lives up in East Texas come down to get him, said he had a match for him. Well, at that time he’d won ten fights, and I had firmly decided to retire him to stud. I said, ‘Oh, son, don’t fight that cock. Please don’t fight that cock.’ But he said, ‘Dad, I’ve got a match made with this old boy who’s got more money than he has sense and it’s just too good a chance to pass up. There’s not a cock in this part of the country can beat that bird. I’ve got to take him.’

“Well, of course I let him because I do with my boy just like my daddy done with me, let him use his own judgment. But, I tell you, I stood out in the front yard damn near with tears in my eyes watching that truck drive off.

“But he come back next day with the cock absolutely unmarked. Had a nice little chunk of money, too. But, I tell you, I took that cock out of the truck and said, ‘Buddy, you are now retired!’ Said it loud, too, so everybody could hear me.”

Most matches are individually made. A handler takes as many cocks to a fight as he thinks he can match and then goes from breeder to breeder looking for a fight and a bet for his birds. Such matches are called “brush fights” because they usually take place out in the country on someone’s private property. The other type of fight is the derby, where a promoter makes the match-ups and there are entry fees and prize money. There may be as many as two or three hundred spectators at a derby, and the betting is fast and heavy with wagers in the thousands.

Morris pointed out a white cock with a few brown markings. “Now this cock fought the longest fight I’ve ever been involved in or ever seen. I don’t know exactly how long it took, but we started in the afternoon and was fighting in this little brush pit that didn’t have no lights. Well, it come on and got dark and those birds were still going after it. Now my cock is white and the other bird can see him, but mine can’t because the other bird is a dark brown. So all my rooster could do was counterpunch. Every time that other cock would hit mine, this little white cock would hit back. Pretty soon my cock got in a good lick and this other bird let out a squawk. Well, that done it. That other bird went to squawking and my bird was finding him by sound. Chased him over in the corner and killed him.”

Morris, like most breeders, gives his cocks a shot of the male hormone testosterone 72 hours before a fight. He says it increases their gameness. He also gives them a shot of some secret preparation fifteen minutes before they go in the ring. He says it stimulates their hearts.

“I’ve been offered a hundred dollars for that formula, but I’m not about to tell anyone. It’s not anything so really special. You can buy most of the ingredients from the drugstore. Course it helps if you know a friendly vet.”

There is probably little mystery to the shot that Morris gives his cocks. It is common practice to give the birds a shot of digitalis to stimulate the heart just before they fight. Many of the more sophisticated breeders give their birds shots of vitamin K to make their blood clot faster, so that when they are wounded by the gaffs they will not bleed to death. And, of course, all breeders feed their cocks a high-protein diet. Their diet is quite different from that of ordinary chickens, even to the addition of vitamin supplements to their water.

Cocks fight their best during the breeding season, and most cockfighters capitalize on this by depriving the cocks access to the hens while they are in training.

“They get very fierce then,” Nano said seriously. “Sometimes they get so tensed up they will try to peck me, which is almost unheard of. And there are some, who know about such things, who give their gallos some medicine that makes them desire the hens even more. But I don’t do that. I do not have to.”

It is not considered unethical to dope a bird. Even though there is an official cockfighting association, there is not a great deal of control. Anything goes that you can get away with. For instance, since the cocks peck each other about the head, some handlers will put poison on their cock’s hackle feathers so that the other cock, pecking there, will become ill.

The gaffs are slightly curved surgical steel weapons that look like large needles. They are supposed to be perfectly round. “But some old boys,” Morris said, “will file an edge on the bottom side. If that diamond-shaped gaff hits bone it will penetrate and likely break the bone, whereas if it’s round it will just generally slide on off. You’ve got to watch for everything in this game.”

The cockfighting season begins, depending on the climate of the locale, in late fall and usually ends in midsummer. This is because the cocks molt during the hot months, and the molting makes them feverish and weak and therefore unable to fight. Of course, some cocks do not shed as much and do not get as sick, and some breeders have a few cocks on hand that are available for hack matches, which are impromptu fights between two breeders.

Even though it exists freely in Texas, cockfighting is illegal here. Laughing, Morris explained how it works: “Well, we don’t exactly rent the auditorium downtown to hold these things, you know. Mostly some old boy will have a pit out on his place in a barn or some such—a place that will maybe hold fifty or seventy-five spectators. Word gets around through our associations and we have a fight. Then a lot of our fights are scheduled ahead of time in our monthly newsletter.

“Course you’ve got to remember that the local law has more important things to do than run around chasing a bunch of old boys fighting chickens. Occasionally, though, some bunch will get all lathered up, and the sheriff will have to make a raid.” He shrugged his shoulders. “When that happens you just pay your fine and charge it up to the price of doing business. No big deal.”

Cockfighting is, however, legal in Louisiana. This is because there doesn’t happen to be a law against it, a fact which was discovered when a sheriff once raided a pit and brought in fifty or sixty defendants and the judge couldn’t find a statute against it. Louisiana is also where the “world championship” of cockfighting is held, in the little town of Sunset. It is a derby. In it a man will fight eight matches with eight different cocks. The entry fee is usually $150 per man, there are about thirty breeders who enter, and it is generally winner take all. The winner is the breeder who wins the most fights, which usually means winning all eight, a difficult thing indeed.

Morris said: “Best breeders and the best cocks in the country. A man has got to have an awful lot of birds to come up with eight of the best because all some hotshot has to have to knock you off is one topflight cock and you’re a blowed-up sucker.” He looked thoughtful for a moment. “I come close one time. Won seven out of eight. Of late they’ve started paying more than one person the money, but I’d rather just see the winner get it all.”

Morris, like all breeders, has no feelings about whether cockfighting is cruel or not. He said: “I don’t think about it one way or the other any more than that guy who raises meat chickens wonders if it’s cruel when he goes to slaughter and process them. I won’t deny I love it, and I won’t deny I get a thrill out of seeing a game bird fight, but I’ll leave the question of cruelty to others.”

It is difficult to say if it is a cruel sport or not. On the one hand, a meat chicken, a capon, is slaughtered at anywhere from eight to ten weeks. On the other, a gamecock will not even be fought before he’s one year old and, during that one year, he will receive excellent care. And then some cocks, like the eleven-game winner, are never killed, but die a natural death. Many are retired to stud after only three or four wins. The question seems to be whether it is less cruel for the cock to be killed by a man rather than by another cock.

Cockfighters say that the humane societies would like to see the breed outlawed so that it would vanish. To some this makes about as much sense as extinguishing that breed of men who have a penchant for dangerous sports. “The gallos,” said Nano, “were fighting long before man took an interest in sparring them. It is their nature just as there are various natures of men.”

A gamecock’s aggression is directed only at another gamecock. A man can hold him, touch him, handle him, and he won’t make the slightest attempt to peck. A dog or cat can play around him and the cock will ignore it. Several breeders said that a fighting cock will not even bother a barnyard rooster.

“Beneath his dignity,” one said. “He’ll just ignore him. Course, it damn near will scare the feathers off that barnyard rooster and he’ll find business elsewhere in a hell of a big hurry.”

Nano says that he does not feel anything personal for his cocks, that it is a business, the way he makes his living. Yet he does something few other breeders do—he names some of his birds. He named Pepito long before he had his first fight, naming him after his sire, Pepe. He said, “Even when he was young there was something special about him, something rare, and I knew he was going to be very good in the ring. Is it correct to say he had a look?”

But now Pepito did not look well. His right eye was swollen completely shut, and he seemed to almost sag down in the handler’s arms. He would react a little when the handler sprayed him with water, but you could almost feel his fatigue. It was as before, the crowd yelling for the fight to go on, the referee motioning the two handlers forward, and Antonio Chapa glaring triumphantly at Nano.

Finally Fernando motioned his handler to bring the cock over. Nano stroked Pepito’s head and looked at his good eye. It gleamed back. He studied him, then sighed. “I think he still wants to make a fight. Pit him.”

They were at the line again, and this time even the pinto was too tired to strain forward. Yet, when the handlers released them, the pinto still jumped higher and spurred more viciously. But Pepito continued to fight back, slugging the pinto with his good right leg just under the wing, getting in sometimes as many as two or three hits as they went up in the air.

The momentum was slowing, and neither cock seemed able to gain an advantage. It even seemed that the head blows the pinto cock was inflicting were less severe. The two handlers hovered just in the background, ready to take up their cocks at the slightest signal from the referee. Outside the ring Nano looked on, his face impassive. But in the ring Chapa exhorted his cock urgently in Spanish.

They went up again and then again and then a third time. Finally, as if by agreement, they both settled to the ground in almost exactly the place they had been pitted. Pepito was listing slightly toward his damaged leg. But there somehow seemed something different about him. He did not seem so tired. His good eye gleamed and glinted as he glared across at the other cock. The referee motioned the handlers to take up their birds, and they had just started across the ring when Pepito suddenly darted forward and pecked the pinto on the head. Instantly they sprang into the air. But this time it was Pepito that hit first and hit the hardest. A few feathers came floating out from beneath the pinto’s wing. The cocks went up again and the pinto did not rise above Pepito for a headshot and again Pepito hit the other with two hard breast blows. When they went up again it was Pepito who was on top, and he hit the pinto in the side of the head with the short, blunt spur. When they landed, the pinto did not jump and Pepito rose above him, spurring now even with his broken leg. Suddenly the pinto let out a loud squawk and turned and ran for the canvas wall. Pepito limped after him and cornered h im against the canvas and leaped up, holding him with that left leg and slugging away with his right, jumping on top of him. Two, three, four, five, six times he hit, almost too fast to follow, holding himself in position with his wings, now on top of the pinto, pecking him on the head and slugging away with his spur. The pinto made no attempt to fight back.

im against the canvas and leaped up, holding him with that left leg and slugging away with his right, jumping on top of him. Two, three, four, five, six times he hit, almost too fast to follow, holding himself in position with his wings, now on top of the pinto, pecking him on the head and slugging away with his spur. The pinto made no attempt to fight back.

The referee hovered over them. Suddenly he threw out his hands like an umpire calling a runner safe, shouting, “¡Se termino!” He reached down and picked up Pepito and held him aloft triumphantly. Those who had bet on the red cock cheered and yelled. Those who had not looked disgusted and blurted insults at Antonio Chapa. Money began to change hands. The referee circled the ring and handed the cock to Nano. He took him, smiling slightly. The cock’s good eye still gleamed.

For a second Fernando stroked Pepito’s head. Then he looked over at Antonio Chapa and began to laugh. Chapa glared back. Fernando laughed some more, then smiled and turned to put the cock in his carrying case.

It was anticlimactic after that. Nano won the second fight, lost the third, and won the fourth. Then it was over and the spectators vanished as quickly as they had come, jouncing back to civilization over the nearly impassable dirt road. Miguel Martinez began to put up his stock of Scotch and beer and soda pop. The woman who had cooked put out her fires.

Chapa had paid and left, but Fernando was slow to leave. He got Pepito out of his cage and examined the bird’s damaged leg and eye. Someone asked if the injuries were very serious.

“Not so very,” Nano said. “The leg will mend itself and the eye is only swollen shut, not harmed.”

Someone else asked if Pepito would ever fight again.

Nano’s white teeth suddenly flashed a large smile. “Oh, yes,” he said, “he will fight again. Only now he will fight the hens only. I think he will like that very much.” He laughed, enjoying the thought. “Yes, I think he will like that very much.”