This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

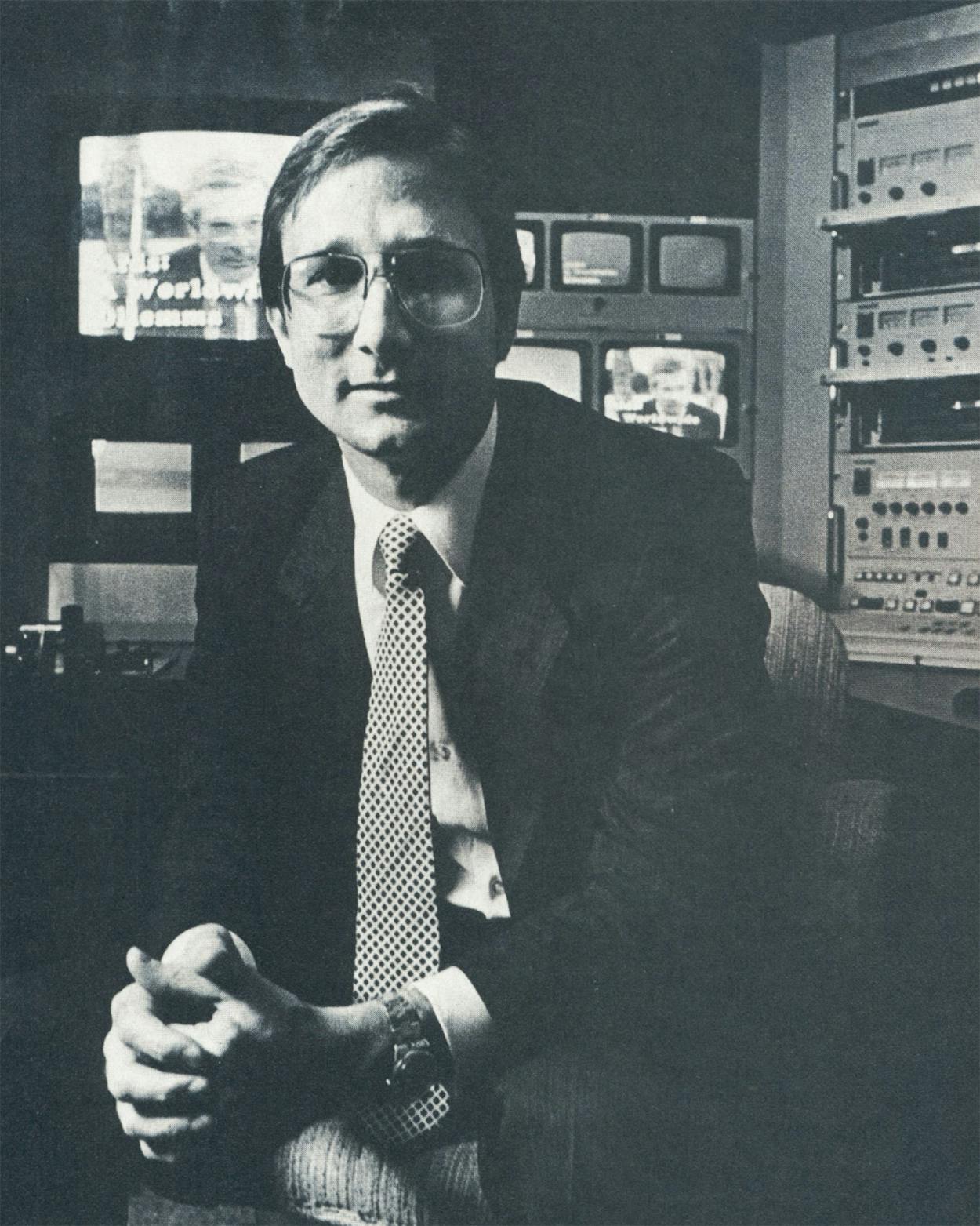

Last year the people at Cannata Communications, a young Houston production company that had never made anything more riveting than an employee-training film, came up with the idea of producing an educational video on AIDS. The plan seemed like a natural, so they devised a scenario that read a little like Head of the Class without jokes, and the company knocked out a film in time to market it this summer to 15,000 school districts all over the country. With roughly $50,000 seed money sunk into the project, company president Jack Cannata, Jr., is gambling that principals and school boards will like what they see, buy the film, and turn his venture into gold.

While the tragedy of AIDS continues its open-ended international run, hundreds of corporations and entrepreneurs are picking up a subliminal message: AIDS is big business. Consider the following. Worldwide, the market for the two established AIDS tests is estimated to be $100 million annually—nice pocket change for companies like Du Pont and Abbott Laboratories, which make them. Investors in New York, London, and Tokyo continue their fickle affairs with the major pharmaceutical companies—snapping up shares as rumors of a new AIDS miracle drug surface, dropping them when a better prospect comes along. In Washington, D.C., the feisty French and American researchers who identified the AIDS virus battled over the rights of discovery, less for the glory than for the millions that may accrue from patents to the key biochemical techniques involved in their research (they finally agreed to share the honor). Some corporations, though, find that AIDS is draining rather than filling their coffers. Insurance companies are threatening to revolt because victims of the virus are taking out big-bucks life insurance policies knowing they will die within a few months.

On a more modest scale an odd lot of smaller businesses, well positioned to take advantage of the situation, are doing fine. Publishers are rushing more than one hundred books on AIDS into print, while manufacturers of latex gloves and condoms have never had it so good. Medical supply companies stand to benefit from proposals mandating the use of “self-destructing” one-use hypodermic syringes designed to prevent drug addicts from sharing needles. One Texas research laboratory has adapted the standard AIDS test as a field kit for use in underdeveloped countries.

Texas—the fourth-hardest-hit state in the United States, with 2,513 cumulative cases—is of necessity a major player in the AIDS business. Although the state is not home base for the larger drug companies, it does have other AIDS-related enterprises, including one that is unique in the country, the AIDS hospital in Houston. Owned and operated by a private for-profit hospital chain, American Medical International, the innovative but financially troubled Institute for Immunological Disorders has too complex a history for this overview. While the institute’s outpatient treatment is a model for AIDS care, its staff reductions and recent controversial policy of admitting no new indigent patients have not yet erased the red ink.

Elsewhere in Texas, even though the variety of enterprises is impressive, the numbers are relatively few beyond the health-care providers and medical professionals directly involved with AIDS. Several large corporations are testing the waters, but most of the risk takers are small businesspeople. This is a look at a cross section of six players in the AIDS business, how and why they got started, and what they are doing. One of them is Cannata Communications.

The Right Place and Time

The actors in the 23-minute video, entitled AIDS: A Worldwide Dilemma, could be the cast of the senior play. The Class Jock, the Class Deb, the Class Nerd, the Class Stud, and the Class Tart all have starring roles. The action takes place on a school campus as thirteen students gather for a special AIDS seminar conducted by two physicians. One of the doctors is portrayed by an actress. The other is Dr. Charles Ericsson, 43, an associate professor of medicine in the department of infectious diseases at the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston and a member of the Commissioner of Health’s Task Force on AIDS.

The dialogue sounds like it was written by Surgeon General C. Everett Koop (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, intones Ericsson, “is a condition that’s associated with a lowered immune, or defense, system, so we are more susceptible to things we call opportunistic diseases”), but the pace soon picks up. “Aw,” smirks the Class Jock, “this is a fag disease. It’s not going to affect any of us. We’re all healthy.” Recognizing a case of lurking homophobia, the teacher corrects, “It’s gay, not fag,” while the Class Deb interjects, “AIDS isn’t just a gay disease.” Before the Jock can open his mouth again, Ericsson admonishes, “Heterosexuals are at risk too.”

As the film unwinds, the students ask questions of the doctors, and they answer realistically and bluntly.

• On sex and AIDS: “I’m not telling you to run right out there and have sex, but if you decide to, then using a rubber is a smart thing to do.”

• On contracting the disease: “The only way you’re going to get AIDS is through direct sharing of body fluids . . . blood, semen, or vaginal secretions. . . . All it takes is a little tear, totally inapparent, and the virus can enter the bloodstream.”

• On oral sex: “If you want to have oral sex, use a condom.”

• On compassion: “I think you ought to treat [people who have AIDS] just like anybody else; after all, they need all the help and encouragement they can get.”

Other answers include advice on drug abuse, trips to Boys Town, French kissing, mutual masturbation, and how to put on a condom.

As of mid-June, Cannata had sent out fifty or sixty preview films to state education agencies and 15,000 order forms to individual school districts. But he didn’t really expect much response until midsummer or even after the start of the school year. Every school official he talked to was enthusiastic about examining a copy of the video, but Cannata realizes that the film’s pragmatic position on condoms and nonjudgmental attitude toward sex won’t sit well with everyone. He does feel that his timing is right, however. “You go through life,” he says, “looking to be at the right place at the right time. Big decisions are being made this summer. All of a sudden AIDS has reached crisis proportions. People are saying, ‘Oh, my gosh, we’ve got to do something right now.’ ”

If Cannata turns out to have a blockbuster on his hands, he stands to make a bundle; he could gross $1 million for 4,000 sales—not bad for a low-budget movie with unknown actors and no plot.

As AIDS business goes, Cannata’s company occupies one of the most useful areas: communication. Currently, education is the only way to combat the spread of the virus. There is a desperate need to get the message across about the spread and prevention of the disease, and health departments and schools typically lack the skills to do boffo attention-grabbing campaigns. (Some of the efforts may have been a little too boffo, though. The governor of Illinois was mortally offended by a rap-music message entitled “Condom Rag,” and in Iowa the mothers of several small children led them silently away from a production of The Wizard of AIDS, in which Dorothy kills the Wicked Witch of Unsafe Sex by suffocating her with a giant condom.)

With more federal money likely to be entering the pipeline from Senator Edward Kennedy’s proposed comprehensive AIDS bill ($450 million for education in a total of $900 million sought), advertising, graphics, and communications agencies may find their services in demand. Even if the firms end up working only for expenses, the goodwill generated could bring a windfall profit of exposure, not to mention the satisfaction of fostering AIDS education where it is most needed, at the beginning of the learning curve. In the words of Dallas doctor Ron Stegman, who has seen enough of the disease to last a lifetime, “We have to educate our kids—or bury them.”

Pick a Number

AIDS is a numbers game, and the numbers seem ready to veer out of control: so many thousands of cases, so many unknown millions of people infected, so many incalculable billions of dollars just to maintain the status quo. One of the largest AIDS businesses in Texas is a laboratory where big numbers—more than two million AIDS tests a year from military contracts—are a fact of life.

It is ten o’clock on a Friday morning at Damon Clinical Laboratories in Irving, and two of the dozen or so lab technicians on the shift are methodically unwrapping the last of seven thousand vials of blood serum. There’s hardly a ripple on the surface of the facility, which is about the size of a high school chemistry lab (but much more antiseptic). The technicians fiddle with their equipment, scan computer screens, and slide batches of serum into the incubator. This is the largest AIDS testing laboratory in the country, and the most striking thing is how serene it all is. No one even looks in a hurry.

The test that Damon runs is called ELISA (it is pronounced “Eliza,” and it stands for “enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay”), and it is the only AIDS screening test approved by the Food and Drug Administration. As lab tests go, it is straightforward and highly automated. A lab technician can finish a batch of ELISA tests plus ten controls in about three and a half hours, two hours of which are spent waiting for the samples to incubate. The procedure begins with the arrival by air package express of dozens of boxes of plastic vials from military bases and recruiting centers all over the country. Once the parcels are checked to be sure that none of the various James Bond–type security devices has been tampered with, a lab technician unpacks the samples. Using automatic equipment, she extracts a small amount of the serum and dilutes it to one two-hundredth of its original strength. She then pipettes each diluted sample into one compartment of a laboratory microplate. A clear plastic rectangular box divided into 96 sections, the microplate looks somewhat like an ice tray for miniature cubes, but much smaller.

The most important part of the ELISA test is invisible. Although the microplates look empty, the inside of each compartment, or well, has an ultrathin coating of antigens from inactivated AIDS virus. If the serum contains antibodies to the AIDS virus, they will bind with this antigen coating and show up as a positive reaction at a later stage of the test.

Having filled the wells with diluted serum, the technician puts the microplate into an incubator to cook for an hour at body temperature. She adds a reagent, a color developer, and a chemical to stop the developer (with intermediate plate washings and two more incubations). Finally she passes the plates through a device resembling a postage meter, which uses fiber optics to scan each well.

This is the moment of truth. If the developer has turned a certain degree of yellow, the color change indicates AIDS antibodies are present. In seconds, the reader finishes a batch and displays the results on a computer screen. Samples that test positive two out of three times are sent to a Damon lab in California for confirmation by the Western Blot test, a more accurate but more expensive procedure. The ELISA is 98 percent accurate; the Western Blot, 99 percent. Depending on the sample, 15 to 50 percent of the ELISAs that show positive are declared negative after the Western Blot.

If there is any area of the AIDS business that has growth potential, it is laboratory testing. Every sexually active person in the country is a potential repeat customer. Damon’s private testing business from doctors’ offices and hospitals is growing exponentially, from 2,100 in December 1986 to 25,000 projected in November 1987. But oddly, the biggest chunk, the $18 million in military contracts, hasn’t made a lot of difference to the company, yet. Joseph Isola, the president of Damon Clinical Labs and a vice president of the Massachusetts-based parent company, Damon Corporation, says, “We were competing for the AIDS testing contract, so our profits are relatively modest. Also, all our labs have grown, so the growth is not just from AIDS. Overall pretax operating profit for Damon Clinical Labs will be ten percent for the year, a good margin in its context.” Stock in the corporation, which had sales of $148 million in 1986, has recently climbed from $16 a share to about $20.

No one wants to ballyhoo earnings from AIDS, but Isola and everyone else in the business knows that coming soon may well be federal contracts for prison and immigrant testing as well as testing for marriage license applicants in some states. The lab with its foot in the door will certainly have an advantage.

When investment analysts look at the AIDS picture, they see two things: glamorous but risky opportunities with pharmaceutical companies that are fishing for an AIDS cure or vaccine, and moderate but stable possibilities with clinical labs that are doing mainly AIDS testing. Shyamal Ghosh with Ivy Securities in Houston is an independent broker and analyst who previously worked for Merrill Lynch and American Capital Management. He notes that AIDS testing contracts are a small part of Damon’s sales—about 6 percent. “But the potential is tremendous because of the scare. In my opinion,” he adds cautiously, “Damon stock presents an investment opportunity.”

Protection Money

The AIDS epidemic has made coffee break conversation of all manner of doctor’s office topics. Now it’s about to bring a former exclusive occupant of the men’s room into the inner sanctum of the powder room. Pay attention next time you’re out, ladies. Alongside the automatic hand driers and the paper-towel, tampon, and perfume dispensers, there may be something you have never seen in a ladies’ room before. In fact, it may be a dispenser you have never seen: a condom machine.

The new respectability of the condom as a defense against AIDS boosted condom sales nationally by 10 percent last year, with women accounting for half the purchases. Now the dispensing machine is shedding its sleazy image too. One of the beneficiaries of this turnaround is Jim Gildart, 42, the owner and general manager of Allcoin Equipment in San Antonio. Allcoin is a wholesale distributor of all types of vending devices, including cigarette, snack, coffee, and pinball machines, pool tables, jukeboxes, and, of course, condom dispensers. Jim Gildart—who looks a bit like an underweight Santa Claus and who never ever uses the word “rubber”—says that business started picking up in June 1986, which was the same time he began to notice a lot of fliers and newspaper ads from previously unknown condom machine manufacturers. “I don’t know what you want to call it—a hundred percent or a thousand percent increase—but before then, sales were zero.” The market is still small, but Gildart thinks it has plenty of promise. He won’t disclose sales figures, but a representative of a major condom machine manufacturer said that its sales are up about 10 percent over the last year and a half, keeping step with condom purchases.

Along with the new solid-citizen image of condom machines, Gildart is finding a different and potentially lucrative type of customer—health and human-service organizations. One manic Planned Parenthood representative wanted to hang condom dispensers on telephone poles (“I think her thought train is a little off there,” observes Gildart mildly). Another possible buyer, the Austin–Travis County health department, is readying a major anti-AIDS campaign with plans for placing condom machines in the one hundred or so public rest rooms in city and county buildings. Most of Gildart’s usual customers, small-route operators, buy ten or twenty machines at a time. Orders like Austin’s could eventually be a thousand or more if the private sector responds to the health department’s publicity campaign.

Anyone in the market for a condom machine will find more variety than even a year ago. Today the equipment comes in what Gildart calls user-friendly colors like pink and blue as well as high-tech stainless steel. Instead of lurid girlie decals, the machines bear rainbows and red medical crosses. And some condoms won’t be sold from condom dispensers at all: at least one maker is putting them in cigarette-type boxes to vend alongside the Virginia Slims. The units that Gildart currently carries are made by the big three condom machine companies: National Sanitary Laboratories (the Cadillac of the industry, he says), ProVend, and Exidy. Prices start at $195 for a basic dispenser and go as high as $450 for Exidy’s more versatile unit, which has such special features as slots that allow two sizes of packaging and a tilt alarm. “A bell goes off if you hit the machine,” Gildart jokes, “and then you run around the rest room like crazy trying to hide.”

Unlike other AIDS entrepreneurs, the makers and distributors of condoms and condom machines didn’t go after a business opportunity; they just got lucky. But having now gotten lucky, they intend to stay that way. Gildart credits Surgeon General Koop for the upturn in his business, kidding, “I just wish Koop had also said for people to put a quarter in a jukebox every time they buy a condom.” In a more serious vein he adds, “You hate to think of why business has grown, but I believe it will continue to increase until there’s some light at the end of the tunnel.”

Seeing Red

Little did Mark Hanten know that his apparently humanitarian idea of starting a self-donor blood bank would stir up so much controversy. In 1985 Hanten, a 24-year-old Houston Xerox salesman, happened to read an article about a young boy who died of AIDS after receiving a blood transfusion during elective surgery. As Hanten recalls, “The kid didn’t even need the operation, and he died. It was a problem that the blood banks had not yet solved.”

The more he thought about it, the more convinced Hanten became that there was an obvious way to prevent such needless deaths. He decided to start an autologous, or self-donated, blood bank, where people could freeze their own blood and store it for future use. He says, “The way I saw it, I could solve the problem and make some money at the same time.”

With the encouragement of his wife, a pediatrician at the Baylor College of Medicine, Hanten boned up on the blood business, quit his job, and incorporated under the name Bloodsavers in November 1985. He and his two part-time employees did little marketing, though. It took three months to acquire institutional accreditation from the American Association of Blood Banks (AABB). “I was very optimistic,” says Hanten. “I thought that as soon as I told people about the service they would beat my door down.”

Unfortunately, the knock at the door never came. Bloodsavers would have been the second autologous blood center in the country, but there was one catch: No one deposited any blood. Within a year Hanten found himself with a $100,000 investment in expensively idle equipment. Furthermore, while the general public was indifferent, the voluntary, or homologous, blood banks were only too aware of the autologous concept. The welcome they gave him was about as warm as a unit of frozen blood.

Bill Teague, the president of the Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center of Houston, is a past president of the AABB who questions the need for a separate system of autologous blood banks. All donated blood is now checked for AIDS, he says, and the chance of getting a bad unit is “infinitesimal” (a recent study by the American Red Cross in Los Angeles indicated the risk may be as high as 1 in 48,000; it all depends on your definition of “infinitesimal”). Advocates of the self-donor banks say that AIDS is not the only problem; a transfusion recipient has a much greater chance, anywhere from 5 to 15 percent, of coming down with hepatitis. Teague responds that scrupulous testing can lower that figure, but Hanten asks, “Why take any risk at all?”

The advocates of the two concepts argue over just about everything else. One especially sore point is whether the autologous blood would be available in an emergency. One side points out that it takes half an hour to thaw and deglycerize the blood and additional time to deliver it, while the other says that only 5 percent of all blood transfused is needed within the first two hours of hospitalization. The cost of storing frozen blood comes in for a few knocks; the charge can range from $50 to $150 a year, plus the costs of freezing, thawing, and delivery. One side says that’s cheap insurance; the other says it is a whole lot more than a unit of fresh red cells from a voluntary bank ($45 at Gulf Coast). But the biggest part of the brouhaha centers on whether, as Teague and others fear, autologous blood banks could undermine the nation’s blood supply by encouraging people to donate exclusively for themselves. Hanten counters that since only 7 percent of the population of eligible donors in Texas gives blood anyway, the claim is exaggerated. The Journal of the American Medical association and the New England Journal of Medicine, in fact, recently published articles saying they felt autologous blood would add to, not reduce, the general supply.

As in most arguments over principles, though, if you listen long enough, you will find a bottom line. And this one is no exception. Voluntary blood banks are classified as nonprofit under the IRS code, but that doesn’t mean they don’t make money. Almost all the blood that is collected from unpaid donors is separated into its various components and sold to hospitals (technically, the collecting is sold as a service, and the blood goes along with it). Anything that reduces the need for blood components, such as autologous blood, reduces sales. Of course, voluntary banks do have the ability to freeze blood (they keep rare blood on ice for emergencies), but to go into that aspect of the business in a big way would mean major changes. Autologous banks, since they are just starting up, don’t have that problem. A disinterested observer might be forgiven for concluding that there is probably room for both concepts.

The blood business is at a crossroads because of AIDS. Hanten’s Bloodsavers failed because it was undercapitalized and ahead of its time, but 25 to 30 other autologous blood banks are either open or hoping to open around the country. One of these is in San Antonio: American Blood Storage opened at the end of March and has collected one hundred units of blood. The huge Daxor Corporation of New York, a frozen-tissue specialist, operates two blood banks in that state and has designs on the rest of the country. “We eventually expect to be in every major city,” including two in Texas, says Daxor’s president, Dr. Joseph Feldschuh, who recently cut a deal with Federal Express to fly blood cross-country when it absolutely, positively has to be there overnight (guaranteed in six hours). Two things can now happen: Either the homologous blood banks will change their tune and move into the autologous business, or they can cede a portion of their territory to the newcomers. In any case, it doesn’t seem that the final bell has sounded.

House of Cards

There’s nothing even remotely funny about AIDS, but its appearance in history in the midst of the sexual revolution has given rise to some strange juxtapositions and equally strange business ventures. In the Houston Chronicle Sunday magazine, sandwiched between ads for the Moulin Rouge Cabaret (“The Finest Gentlemen’s Club in the Area”) and Selectra-Date (“Have you been skeptical of video dating services . . . ?”), you can find a pitch for a different kind of sex-related business:

CONFIDENTIAL AIDS TESTING. $25.

3 DAY RESULTS. MON–FRI 10–7.

CALL 782-5326. 6423 RICHMOND #E.

CLEAN INC.

You may not have realized you needed to be tested for AIDS, but John Bailey and David Rosenfield of CLEAN, Inc., think you do, and they hope that this ad and the pitch they give you on the phone will convince you of the wisdom of having your blood scrutinized.

Rosenfield, 29, and Bailey, 40, are the president and the vice president-founder, respectively, of CLEAN (originally the Concerned League to Eliminate AIDS Naturally, recently changed to the Concerned League to End AIDS Now). It is one of a swarm of enterprises that appeared nationwide around the beginning of the summer, offering walk-in tests and AIDS-free cards. But while the market niche is new, the service isn’t. The test (the ELISA) is exactly the same one you can get free in public health clinics in most larger cities or at your doctor’s office for about $60 and up.

Public health officials and AIDS activists have universally lambasted private testers for waffling on the two things they consider the cornerstones of testing: confidentiality and counseling. And they really froth at the mouth when they hear about safe-sex cards, which they dismiss as worse than useless.

Despite such criticism, Bailey (a former disc jockey in Houston’s topless clubs) and Rosenfield (a scion of the family that owned Nathan’s, a major men’s clothing business) are persisting, convinced that eventually their effort will pay off. They admit that the going has been rough. It has even been something of a comedy of errors. Their first plan was to get the city to endorse them to take some of the load off the public Montrose Clinic, but the city council was not interested. So as a goodwill gesture, Bailey had 105,000 free pieces of AIDS literature printed. The city still wasn’t interested. “You’d think they would have at least said thanks,” grumbles Bailey. So he and Rosenfield worked out their own deal with MPC Laboratories (a large well-established lab associated with Memorial Hospital). They lined up an adviser (Dr. Antonio Milici, a cancer researcher), a physician who would confer with those who wanted more information (Dr. James D. Fenimore, a proctologist who has treated many AIDS patients), and a counselor (their tax consultant, who happened to have a master’s degree in human services). Then they rented a small storefront office in a yuppified area of Richmond Avenue.

Although they advertised, business was not brisk. Figuring that an all-out education-publicity effort was called for, Bailey prepared a flier. On one side it showed an old-time engraving of a tattooed man and the plaintive query, “Let’s Party?” The other side of the flier was a humorous page-long treatise entitled, “Love, Death and the FEAR OF AIDS.” In it, Bailey told of his own conversion on the road to Damascus, in which he forswore the seamy side of singles life, got an AIDS test (he was negative), and embraced clean living.

Bailey and Rosenfield handed out five thousand of the goofy documents downtown and settled back to await the results. The first day they got seventy responses, a third of them crank calls. “People didn’t appreciate words like ‘Condom Condemnation,’ ” which appeared in the treatise, says Bailey. “We also had a couple of calls that sounded very sincere; they’d listen politely, and then they would say, ‘Well, I hope you make a lot of money off of people dying,’ and hang up.” A few people actually came in to get a test.

Next, part of the partners’ advertising strategy backfired. They had been using Pappasito’s Cantina as a landmark in their directions but had to stop when the restaurant objected. Then their friends, who had grown weary of constantly hearing about AIDS and being importuned to have the test, stopped coming to see them so often.

Bailey thinks it will take about a year for the general public to become sufficiently aware of AIDS for CLEAN to prosper: “If we were in New York, Los Angeles, or San Francisco, we would be inundated, and I’d be drawing a salary. It’s sad to say, but not enough people have died yet.”

Since it opened in April, CLEAN has tested some 130 people, with one positive test result. The partners charge a reasonable price (it’s now $35), and they observe anonymity by encouraging all customers to use an alias (says Bailey, rummaging through papers, “I have Typhoid Mary here, Errol Flynn, Betty Grable, Tom Jones”). But the initial consultation may not be all that helpful, and the company’s trained counselor sees only those who test positive. A visit to check out the service resulted in an amiable chat and a brief discussion of the ELISA test, false positives, and the fact that there can be a six-week-or-more lag time after infection before AIDS antibodies show up in the blood. But little was volunteered on prevention except to emphasize that the only 100-percent-safe sex is with somebody else who has tested negative. Suddenly it all became clear: The name “Concerned League to Eliminate AIDS Naturally” meant never having to use a condom.

Finally, what about the CLEAN card? Bailey says, “I feel it indicates someone has more information than your regular barstool person.” But any AIDS-free card encourages the myth that there is a subculture of “safe” singles out there; if you just flash the card, you won’t need to worry about prevention or ask embarrassing questions. The only thing is, how valid is someone’s card after an extracurricular roll in the hay?

The continuing proliferation of walk-in testing services has health officials throwing up their hands, but regulation could cure a lot of problems. City government could require strict anonymity and that personnel undergo educational training so they can explain the basic facts about AIDS to every customer. If cities passed such ordinances, many testers would probably fold their tents and slip away, and the rest might become part of the solution instead of part of the problem.

Housing Shortage

Of all the areas of unfulfilled need in AIDS care, none are more critical than home care and housing. For various reasons many victims have nowhere to live. Some have been abandoned by families and lovers; others fall into a gray area—not sick enough to be in the hospital but too ill to live at home without extra help. Nursing homes in Texas will not admit AIDS patients, and for those who still have insurance, the Byzantine provisions of the policies complicate the matter further. While most policies will pay for hospitalization, they do not have clauses that cover extended nursing care outside the hospital or home help. What happens, of course, is that hospitals then become AIDS dormitories, often at a cost of $250 or $350 a day just for a room.

“Call me in six months, and see what I think then,” says Grover Shaunty, a 48-year-old Houston social worker who is charting unknown territory by opening one of the first private AIDS residences in Texas. At the time he spoke, one person had moved into the home, an older two-story stucco house in the predominantly gay Montrose area. He eventually expects to have six residents, each of whom will pay $1,200 a month for a private room, meals, housekeeping, and the services of a resident supervisor.

Shaunty is one of those open, unguarded individuals with whom a stranger feels an instant rapport, and it’s easy to believe him when he says, somewhat immodestly, “I’m a very successful psychotherapist.” His work at the Houston Clinic and his own agency, A Counseling Place, provides the funds that have allowed him to start halfway houses for the mentally ill and a residence for quadriplegics. In founding a home for people with AIDS, he has confronted obstacles that have made others shy away.

The most daunting obstacle was money, which he overcame by deciding he wouldn’t make any. His charges will just cover costs. “I’ve been doing this kind of thing for twenty-nine years, and I’ve never made a profit,” he says, referring to various living programs for people with disabilities that he has started both in Houston and in New York, his former home. So why does he continue to do it? “My motivation is to provide a service.”

Shaunty initially wanted to open an AIDS nursing home, but he realized that providing skilled nursing care and paying for liability insurance would have made it very expensive ($3,000 to $4,000 a month) and that the rapid turnover and frequent empty beds would have rendered it economically unfeasible. He decided instead to go with the room-and-board concept and let residents contract for care themselves. He also decided to go private. “This way I retain control,” he explains. “If you are nonprofit, people criticize you for not taking everyone and the government regulates you. Why would I want that?” Even so, he doesn’t expect everyone to approve. “As a private person, I cannot provide a welfare service,” he says. “My place is a bridge between totally subsidized indigent housing and subsidized death care. There are a large number of AIDS patients who fall in between these.”

Preliminary signs suggest that the dearth in housing and care may be starting to ease. In Dallas nonprofit groups are trying to open an apartment house and planning a hospice. Houston has a small indigent home and a hospice, and Shaunty has heard rumors of another residence similar to his, but more expensive, for three people. Only time will tell if these experiments work. “We hope that AIDS patients can live happily at our place,” he says, “although we know they won’t live forever after.”

Leadership Vacuum

The AIDS business in Texas presents a frustrating picture. It has variety and ingenuity, but the potential for failure is high, and it hasn’t really seemed to go where the needs are the greatest. Understandably, entrepreneurs have tended to target the well population—more numerous and better able to pay—rather than the sick population. The result is plenty of interest in testing but not a lot in housing and home care.

The problem is that AIDS is a public health crisis. Leadership and funding to combat the epidemic must come from the public sector, from government at all levels. Those two commodities have been conspicuous by their absence in Texas.

Ron Stegman, who served on the commissioner’s task force on AIDS, is particularly outraged: “Funding in Texas is abysmal and disgraceful. Here we are, way up the totem pole in caseload, and most of the Legislature is still stuck back in AIDS 101—‘this is a gay disease’—and they flunked.” State commissioner of health Robert Bernstein spends 40 percent of his time on AIDS, and his voice is tired when he speaks about the problem. “I visited with the governor for the first time about AIDS in June, and he was extremely interested and said the state had to develop a policy, but he wasn’t prepared to talk money at that point,” Bernstein says.

The current state appropriation has nothing in it specifically for AIDS. The approximately $1 million that has been spent on education and prevention has come out of the health department’s general budget and its program for sexually transmitted diseases, including federal grant funds. Next year’s appropriation is up in the air. The House bill has nothing. The Senate bill has set aside $3.4 million over the biennium, and even if that amount passes, critics say that it is woefully inadequate. When you consider that Massachusetts—a state with about 75 more AIDS cases than the city of Dallas has—is proposing to spend $6.3 million for AIDS in 1988, the disparity becomes ludicrous.

To be fair, Massachusetts’ economy has not gone bust. If Texas were enjoying flush times, the budget proposals might have been more generous toward all social services, including AIDS prevention and education. Then again, they might not. Commissioner Bernstein observes, “It gets all mixed up with politics and morality. I had one legislator tell me, ‘Doctor, it comes down to the fact that these people with AIDS have broken a law or the moral code.’ I explained that my duty is to protect the health of the state. We’re not sure some of the members understand the seriousness of the problem.”

The private sector can play an important role in every area of the campaign against AIDS, from the earliest stages of education to the last stages of hospice care. In some ways, in fact, private enterprise has been leading the way in Texas. As Jean Settlemyre, the president of the Foundation for Immunological Disorders in Houston, says, “The first AIDS hospital in the world is private because the federal and state governments have been so slow.” But no matter how laudable it is, individual initiative remains just that—individual and isolated. The fragmented efforts that exist now will never coalesce until there is a comprehensive plan of action and money to carry it out. If the present zero-level funding in Texas continues, the chance for public and private entities to pull together and contain the epidemic may pass us by.

The Crushing Cost of Aids

For a victim, the disease is a losing proposition in every way.

Doug Goodell, 27 years old, is wearing jeans and a short-sleeved shirt that shows just how much weight he has lost—54 pounds since he developed AIDS a year ago in May. Before the disease was diagnosed, Goodell was earning $2,000 a month, had a wallet full of credit cards and two checking accounts, and had recently bought new furniture. Since then, he has been living each month on $441 in Social Security disability payments and $17 worth of food stamps—recently reduced to $7. “My gold card is my identification card for the Harris County Hospital District,” Goodell says wryly. “It gets me nearly all my medication. This blue card is from the AIDS Foundation of Houston, and it entitles me to go to their food bank. I have no car, no bank account, and I owe three thousand dollars on miscellaneous credit cards. So there you have my financial status—broke.”

Estimates of what it costs to care for an AIDS victim through the course of the illness in Texas tend to average $60,000, and that’s just the cost to the public health system and the insurance industry. The Texas Department of Health estimates that there will be 13,700 new AIDS patients in Texas between 1987 and 1991. The cost of caring for those who are indigent—like Goodell —will reach at least $30 million a year by 1991. If the federal government must also foot the bill for the person’s living expenses, the costs go higher; they are $5,000 a year for Goodell. To understand where all the money is going, look at Doug Goodell’s bills; they show what really happened to the life of one man who came down with AIDS.

Goodell moved to Houston from rural Ohio in 1979. His parents, who are divorced, and his three siblings didn’t accept his homosexuality (“It’s never really been discussed,” he says), and he felt he had no future in his hometown. In Houston he worked in purchasing and control at various places, but he lost his most recent job after he went into the hospital for the first time. With that job went any hope of getting medical insurance.

While Goodell waits to see how long his condition will be stabilized by AZT (azidothymidine, a powerful but toxic antiviral, marketed as Retrovir), he does his best to keep up appearances. “If you lie around and moan, the disease just feeds on your depression,” he observes. His apartment, an efficiency near the Summit, is immaculate. But the apartment complex as a whole is slightly seedy (the charred hulk of a burned-out wing stood for weeks), and the sheets on his bed have been washed so often that the vivid zebra stripes are starting to fade. He pays $285 a month for rent, utilities included, and about $70 on his phone bill, mainly for calls to his family in Ohio. Occasionally his father sends him a modest check. His clothes, haircuts, and transportation are all donated by friends. The $93 left over after rent and phone goes toward food and cleaning supplies.

One irony of having AIDS is that the small luxuries most people can give up in hard times—maid service, air conditioning—quickly become essentials. Goodell’s apartment must be kept free of bacteria and molds, yet any exertion, even cleaning, exhausts him. Texas Home Health, paid for by Harris County, provides a five-hour-a-day housecleaner who also prepares breakfast, accompanies Doug on a morning walk when he feels up to it, and does his grocery shopping. Air conditioning helps prevent recurrences of asthma and pneumonia.

By far the most expensive item is medical treatment, paid by Jefferson Davis County Hospital and Medicaid. Between June 10, 1986, and March 11, 1987, Goodell was in the hospital eight times for a total of 55 days. His bills, including inand outpatient services, fill 35 single-spaced computer printout pages, which itemize an endless cycle of intravenous solutions, barium X-rays, pills, oxygen, and blood studies. County and federal governments together have paid out $54,156 for his care.

Although he is not in the hospital now, Goodell is still on massive medication. The bedside table in his apartment looks like a pharmacy. His most overwhelming opportunistic infections are Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, now controlled (“i’m breathing on a lung and a half”), cryptosporidium (a one-celled intestinal parasite that causes diarrhea), cytomegalovirus (which causes flulike symptoms), and thrush (a fungal growth inside the mouth and throat that can cause sores and close off the esophagus). Besides taking antibiotics and antifungals for those, he uses numerous antihistamines, decongestants, and inhalants for sinus infections and asthma. “And finally,” Goodell concludes, “there is the all-important, almighty AZT.” The drug saved his life this year. “In December I was in a wheelchair, and the AIDS virus was running rampant in my body. I had gone home to die.” The medication, although life-sustaining, causes anemia and nausea (“It’s eating up my insides,” says Goodell). The drug is also expensive: Each pill costs $3.86 (recently raised from $2.70), which will increase the yearly cost from $11,826 to $16,507.

Goodell’s story is typical of most AIDS victims’. In addition to the toll AIDS has taken in human suffering, it has created a new class of indigents: young people who otherwise would be contributing to the social welfare and insurance pools but who instead are drawing from them.

“I’m hoping for a cure and to be able to return to work. Every morning when I wake up and see daylight, I’m saying a little prayer,” Goodell says. But anything short of a total cure could be a catch-22. If Goodell should be able to work again, he would forfeit his Social Security and Harris County medical support while remaining uninsurable. Until then, if AZT prolongs his life without making him well enough to work, Goodell will continue to eke out a borderline existence on the county and federal dole. —P.S.

- More About:

- Health

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston